1959 German Grand Prix race report: Maranello masterclass

Ferrari take 1-2-3 in two-heat German Grand Prix

Tony Brooks, Stirling Moss, Masten Gregory, Jack Brabham, Jo Bonnier and Dan Gurney on the banked North Turn.

© LAT Photographic

As a result of various political and financial manoeuvres the German Grand Prix left the traditional Nurburgring this year and took place on the AVUS track in West Berlin. Apart from the added complications of getting to West Berlin the move was not popular with drivers and entrants as the AVUS track bears no resemblance at all to a Grand Prix racing circuit, as exemplified by the Nurburgring. Being 90 per cent a pure speed track it was felt that holding a leg of the Drivers’ World Championship on the AVUS was to make an absurdity of the whole thing.

On the other hand those people who think that a World Champion Driver should be able to drive anything, anywhere, anytime, partly approved of the move to West Berlin as it meant that any potential World Champion would have to demonstrate that he can drive on a track as well as a road. Until the title is changed to World Road Racing Drivers’ Championship, there is not much argument against this train of thought. However, be that as it may, the 21st German Grand Prix was moved to AVUS and all the regular Grand Prix teams crossed the Eastern Zone of Germany, either by plane or Autobahn and were ready for the first practice session which was due for Thursday afternoon.

Qualifying

With average speeds of nearly 150mph envisaged the AvD who organised the race took it unto themselves to make some additional rules, overriding the standing rules for FIA Championship meetings. Instead of being for a minimum of two hours, or 300 kilometres, the German Grand Prix was arranged to run as two Heats of one hour each, the overall classification being by addition of the drivers’ performances in the two Heats, those finishing Heat 1 being allowed to start in Heat 2. This was done in the interests of tyre safety, it being felt that one hour on the AVUS would be enough for the Dunlops. Also the regulations forbade any attempts at streamlining, all the cars having to have all four wheels exposed. As a result the whole entry arrived in just the same condition as they would have done for Nurburgring, apart from high axle ratios, stiffer suspension and engines tuned for out-and-out speed.

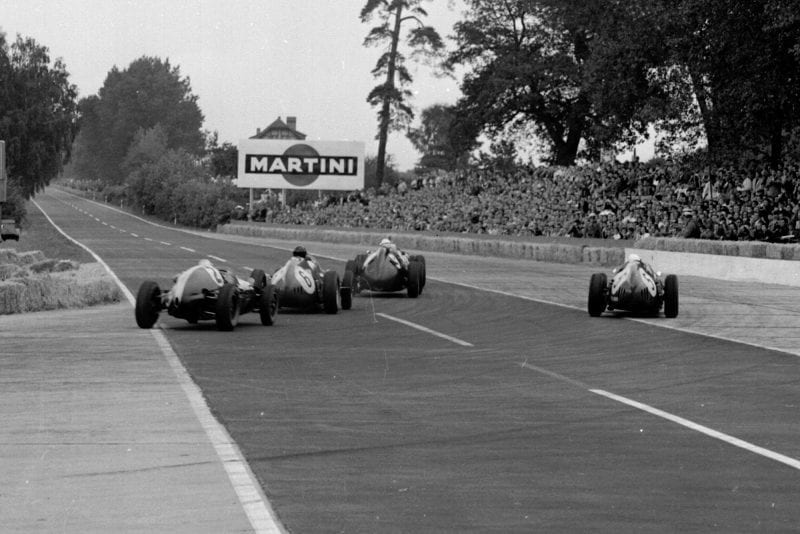

Tony Brooks -Ferrari Dino 246; Stirling Moss – Cooper T51; Dan Gurney – Ferrari Dino 246; Jack Brabham – Cooper T51.

© LAT Photographic

This was not to be the first occasion on which Formula 1 cars had appeared on the AVUS for there was a race held in 1954, at which three Mercedes-Benz gave an unchallenged demonstration run and during which Fangio set a lap record in 2min 13.4sec, a speed of 224.0kph (approximately 139 mph). In pre-war days the then current Grand Prix cars used regularly to compete at the Avusrennen, a meeting in addition to normal German Grand Prix. In those days the AVUS track was longer at the southern end, allowing much higher speeds to be reached on each leg of the Autobahn which forms the major portion of the circuit.

From the start the track runs dead straight down the right-hand leg of the Autobahn, round a full-throttle left-hand curve after about two kilometres and then straight for another two kilometres to the southern turn. In spite of almost nation-wide misapprehension amongst the daily papers in England, this South Turn has no banking whatsoever, being, in effect, a simple hairpin from one leg of the Autobahn onto the other leg. A large section of the grass centre strip of the Autobahn has been replaced by concrete, and further concrete aprons have been laid on each side of the Autobahn, so that by using straw bales to line the track a large radius hairpin bend can be formed in which the cars change direction 180deg from running southwards on the Autobahn to running northwards on the adjoining leg.

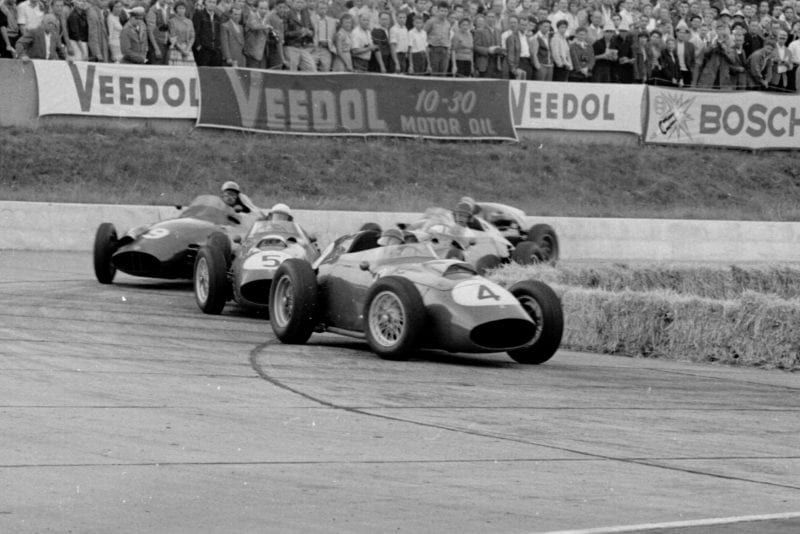

Jo Bonnier driving a BRM P25 leads Dan Gurney and Phil Hill in Ferrari Dino 246) and Bruce McLaren in hisCooper T45 Climax out of the Hairpin.

© LAT Photographic

This large radius hairpin necessitates negotiating a gentle right-hand curve on the approach, which is made all the more difficult as it is in the braking area. The area of the hairpin is very large, allowing many different lines to be taken round it, turning late and accelerating up to the Autobahn proper, or turning early and running out wide and using the concrete apron on the exit and having to accelerate through a gentle right-hand curve back onto the Autobahn. As the whole Autobahn is tarmac covered, and the additional bits of ground at the South Turn are of concrete the 180deg turn calls for crossing from tarmac to concrete, back across tarmac, concrete, tarmac, concrete and tarmac again as the reverse leg of the Autobahn is reached.

“All these changes of surface were calculated to upset the more sensitive drivers, which is exactly what they did”

All these changes of surface were calculated to upset the more sensitive drivers, which is exactly what they did. Back on the northward run of the Autobahn it was full-bore again for about 3½ kilometres to a flat-out right-hand curve leading off the Autobahn and on to the notorious North Curve. This is a tight-radius curve banked at something like 45deg, with the lower half sunk down below ground level. This tight steep banking turns through 180deg and merges back on to the northward leg of the Autobahn, but pointing southwards. At this point there is no centre strip to the Autobahn for nearly half a kilometre, so that the circuit runs diagonally across this open space from the exit of the North Turn to the right-hand, or southward leg of the Autobahn and the circuit is started again, the time-keeping line being across this wide open space of double Autobahn.

The total length measures 8.3 kilometres (approximately five miles) and calls for high maximum speed, heavy braking from 170-180 mph down to 50 or 60mph for the South hairpin, more maximum speed and heavy braking again down to about 110-120mph for entering the banked curve. In the days long ago when the banking was built it is doubtful whether many cars could exceed 120mph, and as the old South Turn, some kilometres further down the double-track road, was a very large radius sweep, with a banking of some 10-15 deg, the whole thing could be considered as pure track racing, akin to Montlhery, Brooklands, or Monza.

Phil Hill pilots his Ferrari Dino 246.

© LAT Photographic

Since the war and with the introduction of the shortened circuit with no banking whatsoever at the South Turn, the track has become a freak for which it is difficult to prepare a car correctly. The steep North Turn is built of bricks with very little science applied to the curvature so that a car does not find a natural line round the banking, as at Monza or Montlhery, and cars have to be physically steered round it as if round a normal corner. At the top the bricks rise vertically for about two feet and then there is a wide flat ledge, also made of bricks. The whole affair is built up on an earth foundation, but by sinking the lower half of the banking into the ground, as at Monza, the height above the ground behind the banking is about about 15-20 feet.

The area behind the banking is a concrete apron used as the paddock, while the pits are situated well down the southward-bound leg of the Autobahn; with the time keeping and main grandstands along the open area at the exit of North Turn, the three major nerve centres of a race meeting are completely out of touch with one another, which does not make for smooth running of a meeting, while it makes it quite impossible for anyone to keep in touch with what is going on.

Qualifying

The first afternoon of practice saw all the entrants trying to adjust their suspensions, tyres and so on to the heavy G-loads of the banking, yet still make the cars controllable on the flat-out curves and the slow South Turn. In addition terminal velocities were being discovered on the dead flat lengths of Autobahn, while drivers were trying to acclimatise themselves to the brick banking. The Scuderia Ferrari fielded four cars, driven by Brooks, Phil Hill, Gurney and Allison, though the last-named was only a reserve runner. They were not far out in their estimation of the maximum speed of their cars, for they were pulling 8,500rpm in top gear, with 8,600rpm if they got a good run off the banking.

Jack Brabham pushes his Cooper T51 Climax) around the banked North Turn.

© LAT Photographic

The Cooper team of Brabham, Gregory and McLaren were not as fast, though they could sit in the Ferraris slipstream and were pulling very high axle ratios to try and conserve the Climax engines. The cars of Brabham and McLaren were fitted with new wider gears in the step-up ratio between the clutch and gearbox, while Gregory retained a set of the older narrow gears. The Equipe Walker had a brand new Cooper-Climax, with a special engine from Coventry for Moss, and their regular Formula 1 Cooper-Climax for Trintignant. The new car was quite standard Formula 1 specification, apart from the gearbox, which was, of course, one of special five-speed ones.

Their first practice was not encouraging as they were over-geared, expecting too much speed from the Climax engine. BRM had two cars entered for Schell and Bonnier, and a third car as a spare. They had been over earlier with Dunlop engineers and one car to do tyre tests, and had then flown two more cars out at a later date. With Moss driving for Rob Walker, the BRP syndicate were left high-and-dry with their pale green BRM so they contracted for Hans Herrmann to drive for them; a popular move with both the organisers and the paying public.

Almost under sufferance the A.v.D. accepted two works cars from Lotus, to be driven by Graham Hill and Ireland, but hoped for better performances than had been seen in previous races. They were quite simply lacking in maximum speed and could not cope with the works Coopers, while Ireland was in trouble with a broken chassis and engine on the first try-out.

In order to give the race some semblance of a German flavour the A.v.D accepted two Porsche single-seater F2 cars, the factory one driven by von Trips, and the special blue one of Jean Behra, who was still driving for his own account, not having signed up with anyone after leaving the Scuderia Ferrari. Both cars were quite outclassed on maximum speed and it was typical of the organisation of the whole meeting that they were included in the entry. There was one further reserve, which was a Cooper-Maserati from the Scuderia Centro-Sud, driven by Ian Burgess.

Dan Gurney takes his Ferrari Dino 246 around the banked North Turn.

© LAT Photographic

Some idea of the progress made in Formula 1 machinery since 1954 can be seen by the ease with which the old record lap of 2min 13.4sec was improved upon by many drivers at their first attempt. Gurney got down to 2min 09.6sec, while Schell and Allison did 2min 11.9sec and Brooks 2min 12.1sec on the first afternoon. Brabham, Bonnier and Gregory also improved on the existing record with 2min 12.6sec. When practice finished chaos reigned, for the paddock were about to send out a bunch of sports cars for practice before the Grand Prix cars had been cleared from the pits.

“Some idea of the progress made in Formula 1 machinery since 1954 can be seen by the ease with which the old record lap of 2min 13.4sec was improved upon by many drivers at their first attempt”

The time schedule was such that the A.v.D. had made no allowance for gathering up tools and materials, fitting soft plugs and generally packing after practice for the Grand Prix cars was finished and with the pits and paddock being so far apart one official had no idea what the next was doing, so that Thursday practice for the Grand Prix ended in some pretty violent shouting matches between entrants and organisers. Not content to run the Grand Prix the organisers were also putting on a sports car race, a touring car race and a Gran Turismo race when they would have had quite enough to do with organising the Grand Prix properly.

On Friday practice continued all day for one class or another, the Grand Prix cars having a session in the morning and another late in the afternoon. Lap times were progressively reduced as cars were adjusted for the freak conditions and as drivers became braver at taking the banking, but not everyone turned out for both practice periods, though everyone was out at some time during the day. Allison surprised everyone by putting in a lap at 2min 05.8sec, a speed of 237.5kph (approximately 147mph), but not himself as he made use of his team-mate’s slipstream to pull out some extra speed down the straights.

Maurice Trintignant in a Cooper T51 Climax lleads Jo Bonnier in a BRM P25 through the Hairpin.

© LAT Photographic

Gurney was taking to this high speed motoring with great relish and improved on his first day by getting down to 2min 07.2sec and in two brief laps Moss equalled this time, though the Cooper-Climax looked very wild as it went round the banking. In contrast the Ferraris looked safe enough but they were giving their drivers a very bumpy ride and springs and shock-absorbers were taking punishment. Brooks and Brabham were only 0.2 of a second slower than Moss, while Gregory recorded 2min 07.5sec and Phil Hill 2min 07.6sec, everyone else being slower than 2min 10sec, the BRMs and the Lotus having insufficient maximum speed.

Lunchtime on Saturday there was a further hour for the Formula 1 cars, during which time Moss improved to 2min 06.8sec, and Bonnier and Schell got down to 2min 10. sec. After this short session a saloon car race took place over 10 laps, during which time the fine weather broke up and continuous rain began to fall. At 4:15pm a 1,500cc sports car race was held over 25 laps and the entry consisted of Bonnier and von Trips with works RSK Porsches, and Behra, Walter, de Beaufort, Seidel, Goethals and von d’Orey with private RSK Porsches. To make up the field there were two OSCAS and two Lotus, Buxton with a Fifteen and Campbell-Jones with a Seventeen.

Rain was still falling when the start was given, after the competitors had done a lap of inspection at about 80mph behind a Porsche coupe, and the way everyone slid about on the starting grid it was obvious that the Avus track in the wet was like an ice-rink, to say nothing of the condition of the polished bricks on the banking. The race soon resolved into a private dice between Bonnier and von Trips with Behra trying his utmost to break them up with his privately-owned car, and this he succeeded in doing on the opening lap.

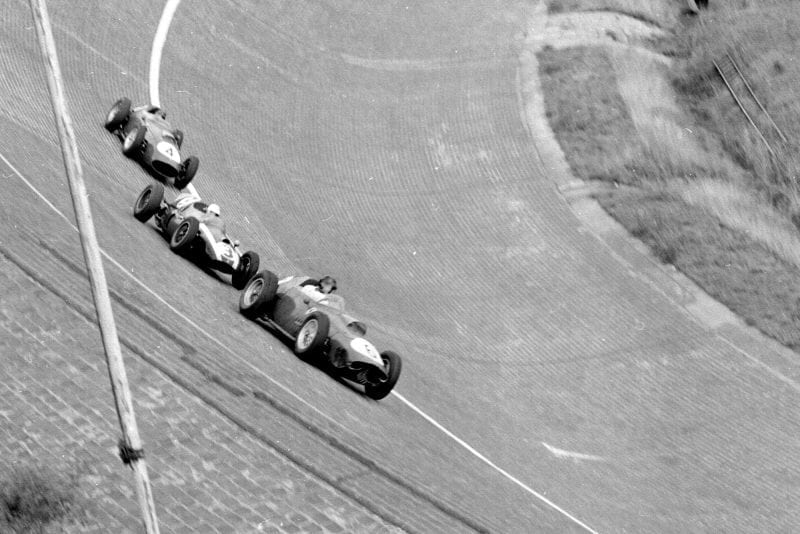

Dan Gurney in a Ferrari Dino 246 leads Masten Gregory driving a Cooper T51 Climax and Tony Brooks in a Ferrari Dino 246 on the North Turn.

© LAT Photographic

On the second lap as von d’Orey was coming off the banking his Porsche began to snake and then he spun helplessly off the banking and across the double-Autobahn to end up with a crunch against the concrete wall of the grandstands, luckily without hurting himself. Although the rain had ceased, everywhere was very wet and slippery and on the next lap as the Porsches went round the banking in line-ahead formation the fourth one, driven by de Beaufort suddenly spun and careered up the banking, mounted the ledge at the top and had almost spun to a standstill before it rolled gently over the edge and disappeared out of sight down the steep grass bank and into the paddock. A few moments later it reappeared out of the paddock gate and rejoined the race by way of the Autobahn and de Beaufort went on apparently unconcerned, with the front all smashed in. It took the organisers two more laps to recover from their surprise and black-flag the Dutchman to a stop, for the car could not possibly have escaped some major damage to its suspension or chassis after such an almighty incident.

“De Beaufort suddenly spun and careered up the banking, mounted the ledge at the top and disappeared out of sight down the steep grass bank and into the paddock”

Meanwhile Behra was hanging on to the tail of the two works Porsches, and as they rounded the banking for the fourth time his Porsche suddenly lost adhesion on the rear wheels, and like de Beaufort and von d’Orey before him, Behra was spinning helplessly on the ice-like surface. The car rode backwards up the banking, over the ledge and struck a concrete block-house which almost severed the Porsche in two. The unfortunate driver was hurled out and killed instantly when he struck a flag mast.

At the other end of the circuit Campbell-Jones and Munaron had collided their Lotus and OSCA, and both retired with torn bodywork, and the whole race had turned into a shambles, brought about by the incredibly slippery nature of the circuit while it had been raining. After all these accidents, the race as such lost interest, and the two works Porsche drivers drove round and round, playing games between themselves, with the German driver finally being allowed to cross the fine first. Once the rain had stopped the banking dried out surprisingly quickly and it was obvious that the organisers were not fully aware of local conditions, or they would have held up the start of the race for 30 minutes or more, by which time the dangerous slippery conditions would have passed.

The death of Jean Behra cast a gloom over the whole meeting and though there was an hour of practice still left for Formula 1 cars very few people took advantage of it. However, the Ferrari team came out and Brooks put in some very fast laps, improving his time first of all to 2min 06.6sec and then 2min 05.9sec, showing that Allison’s time of the day before was no fluke. As a result of the accident Porsche withdrew their Formula 2 car from the Grand Prix, and this meant that both Allison and Burgess were allowed to start, but being a reserve, Allison’s practice time did not count and he was placed on the back of the grid in spite of having made fastest lap.

Race – Heat 1

On Sunday the weather still looked unsettled so the organisers decreed that should it rain a yellow light would be switched on and while it shone no one was to go above the central white line round the banking, and there should be no overtaking in the area of the banked North Turn. The start was due at 2pm, but it was nearly 2:30pm before the cars were assembled on the grid, having had three free laps for inspection of the track, during which time Gurney found he had a faulty front wheel on his Ferrari and the car was hurried back to the paddock to have both front wheels changed. The line up was as follows:—

See table (grid formation)

While the flag was hovering for the last five seconds Gurney and Brabham were over eager and both began creeping forward so that the rows behind began to follow them, and then when the flag fell they both faltered and it was Moss and Brooks who went away in the lead with Gregory right behind them from row two. The fifteen cars streamed down the Autobahn to the South Turn, where they all bunched together and then strung out again along the return leg of the Autobahn and in the order Brooks, Gregory, Moss, Brabham, Bonnier, Gurney, Phil Hill, Schell and the rest, they swooped round the banking and away down the straight again.

Moss had not gone far down the straight on lap two when the transfer gears between the engine and gearbox stripped and that was the end of his race. Gurney got over his bad start and went by Gregory and Brabham into second place, while Brooks still led, but on lap three Gregory went by the lot and took the lead as he went round the banking with the Cooper literally sliding, closely followed by Brooks, Gurney, Brabham, Phil Hill and Bonnier. Then there was a short break and McLaren, Schell, Trintignant and Graham Hill went round equally close together, with Herrmann not far behind and Burgess and Ireland already way back out of the running. Allison had stopped on lap three with clutch trouble, so there were only 13 runners left.

Stirling Moss leads Maurice Trintignant both in Cooper T51 Climaxs and Carroll Shelby in an Aston Martin DBR4/250 into the hairpin.

© LAT Photographic

On lap four the lead changed again and Brooks was back, followed by Gregory, Brabham, Gurney, Phil Hill and Bonnier and on the next lap Gurney and Brabham changed places. There was nothing to choose between the Coopers and Ferraris, though Bonnier in the BRM was now beginning to fall back, and it was obvious that the Coopers were using the Ferraris’ slipstreams to keep up the pace.

As the leading five cars arrived at the South Turn with the brakes hard on Gurney’s Ferrari rode up one of Gregory’s rear wheels and close up the Ferrari nose cowling before it dropped back on the road again. However, this did not cause the engine to overheat and Gurney stayed in the bunch giving as good as he got.

After seven laps Brabham began to ease off a little and dropped back from the cut-and-thrust of the leaders, but Gregory had no intention of giving up and came round the banking almost touching Gurney’s tail and then pulled down below the Ferrari as they came off the banking and they went down the straight almost side by side, behind Brooks who was still leading, and next time round Gregory was sandwiched in second place between Brooks and Gurney and enjoying every minute of it. The four leading cars were all lapping at around 2min 06sec or not far short of 150mph, and neither Brooks, Gurney nor Gregory seemed to have any advantage.

Phil Hill was holding no in fourth position, but down the straights he was reaching 9,000rpm in top gear; unbeknown to him his teammates were only doing 8,500-8,600rpm, pulling the same gear ratio, so that his rev-counter must have been faulty, but thinking the other two were getting too enthusiastic and over-revving, he began to drop back rather than risk blowing up his engine. The result was that the lead now developed into a three-cornered battle between two Ferraris and a Cooper and one lap Gregory would lead, the next Brooks would lead, then Gurney would have a go, and sometimes they came off the banking almost line abreast.

Tony Brooks’ Ferrari Dino 246 on the banked North Turn.

© LAT Photographic

On lap 15 Brahham’s luck was out for he came round the banking with a horrid grinding noise coming from the rear which subsequently turned out to be sheared transfer gears between the engine and gearbox, the new wide ones having failed. Both Lotus cars had long since fallen by the wayside and Schell, Trintignant, McLaren and Herrmann had caught Bonnier and the five of them were in a tight bunch dicing for fifth place, while Burgess had been lapped by the leaders and was bringing up the rear.

Had the two leading Ferraris been driving as a team and not as individuals out to get points for the World Championship, they could have easily got rid of Gregory. As it was the Cooper did not get shaken off and the battle continued for lap after lap, Brooks being credited with the lap record in 2min 04.5sec (240kph average).

“Gregory led but had the two Ferraris almost touching his tail, and on lap 23 Brooks led once more and Gregory was the meat in the sandwich”

On lap 21 Brooks led, but had Gregory alongside him past the pits, on lap 22 Gregory led but had the two Ferraris almost touching his tail, and on lap 23 Brooks led once more and Gregory was the meat in the sandwich. On lap 24 it was all over, for as they went down the straight a big-end bolt broke in the Climax engine and bits and pieces flew in all directions and Gregory’s terrific effort was finished.

The three Ferraris now had things all their own way and slowed right down, taking it easy as they lapped the group who were still dicing for fourth place now, being led in turn by Bonnier, Schell and McLaren. As Gurney lapped them McLaren tucked in behind the Ferrari and got a tow thereby shaking off the others and being sure of fourth place, leaving Schell and Trintignant to cross the line almost in a dead heat, the BRM just ahead. Brooks, Gurney and Phil Hill completed the first Heat of 30 laps in that order, the remaining six runners being a lap behind.

There was a break before Heat 2 took place, during which time Allison’s clutch was repaired and Hill’s Lotus was made a runner again, while Gurney’s Ferrari had it’s nose cowling beaten out straight. The cars were lined up in rows of four-three-four in the order of finishing Heat 1 and Allison and Graham Hill lined up at the back, but just before the start was given the organisers changed their mind about letting them start and they were both sent back to the paddock.

Race – Heat 2

Tony Brooks in a Ferrari Dino 246 leads into the Hairpin.

© LAT Photographic

A very depleted looking field of nine cars was ready for the start of Heat 2 and it was McLaren who shot off into the lead, while Schell made bad start and got left behind. McLaren did not lead for long, for all three Ferraris and Bonnier’s BRM went by him on the straights, and lap one saw the order Phil Hill, Bonnier, Brooks, Gurney, McLaren, Trintignant and Herrmann, with Schell and Burgess already a fair way back. Brooks took the lead on lap two, but Bonnier was still splitting the Ferraris, and on lap three the BRM dropped to sixth place and it was McLaren who split the Maranello team, the first seven cars still being almost nose to tail.

On lap four the Ferraris took command but McLaren was still holding on, in fourth place, but the rest had dropped back and this situation lasted until lap seven when the Cooper’s transfer gears stripped, just as Brabham’s had done and McLaren coasted to a rest. It was now all over, and the three Ferraris gave a demonstration run, lapping at around 2min 14sec and taking turns at leading, being nearly half a minute ahead of Bonnier and Trintignant who were having a wheel-to-wheel battle for fourth place, changing positions almost every lap.

Schell had fallen way back with a slipping clutch, due to his car having been fitted with an obsolete type of clutch plate, and he was limping round hoping to finish the 30 laps, but was now way behind Burgess. At the same time as McLaren had come to rest on the approach to the North Turn, Herrmann was in big trouble at the South Turn with the pale green BRM, for the front brakes had given out and the car had struck the straw bales and gone end-over-end, smashing itself to pieces. Herrmann was thrown out and escaped with minor abrasions, but the car was reduced to scrap-metal.

Jo Bonnier in his BRM P25)

© LAT Photographic

There was little interest in watching the Ferrari demonstration, all eyes turned to the dice for fourth place, but this only lasted until lap 21 for then Bonnier had the throttle linkage to one of the double-choke Weber carburetters come adrift and he came limping round running on one carburetter. It was repaired at the pits and he rejoined the race going as well as ever, but he had lost nearly half a lap. Schell’s clutch finally gave out and he stopped by the line and pushed the car home when the three Ferraris completed their 30 laps in team order, Brooks, Hill and Gurney, their racing numbers being 4, 5 and 6.

They did their lap of honour in line abreast and made a fine sight as they went round the steep banking with Brooks in the middle of the banking, Phil Hill above him and Gurney below him, then peeling off and coming up to line in a close group. Of the 15 starters only seven were left at the end and only the three Ferraris completed the full 198 kilometres. To complete a rather poorly organised German Grand Prix the “wrong” Italian National Anthem was played for the Ferrari victory. By addition of the results of the two Heats the Ferrari team were classified in the order Brooks, Gurney and Phil Hill.

As if there had not been enough racing already, a Gran Turismo race was now held over 15 laps, comprising three classes, the 1,300cc class being a fight between Alfa Romeo Giuliettas and a pair of Lotus Elites, the 1,600cc class being an all-Porsche affair, and the over 1,600cc, class a race between three American servicemen with Triumph TR3s. Much to the annoyance of the Alfa Romeos, including the hottest one in Germany, David Buxton walked away with the race in his private Elite and won with ease, though Warner in the other one retired with engine trouble, and once again the Union Jack was raised and God Save the Queen was played in honour of the dark blue Lotus Elite that had gone so fast, in practice as well as the race. Many well-known Germans in the racing game were seen sniffing around it afterwards for following on the 1,300cc Gran Turismo class win earlier this year at the 1,000-kilometre race, by Lumsden and Riley, the Elite in private hands has shaken the superiority of the Alfa Romeo in this category.

Dan Gurney in 3rd position with winner Tony Brooks 1st position and Phil Hill 2nd position, on the podium.

© LAT Photographic