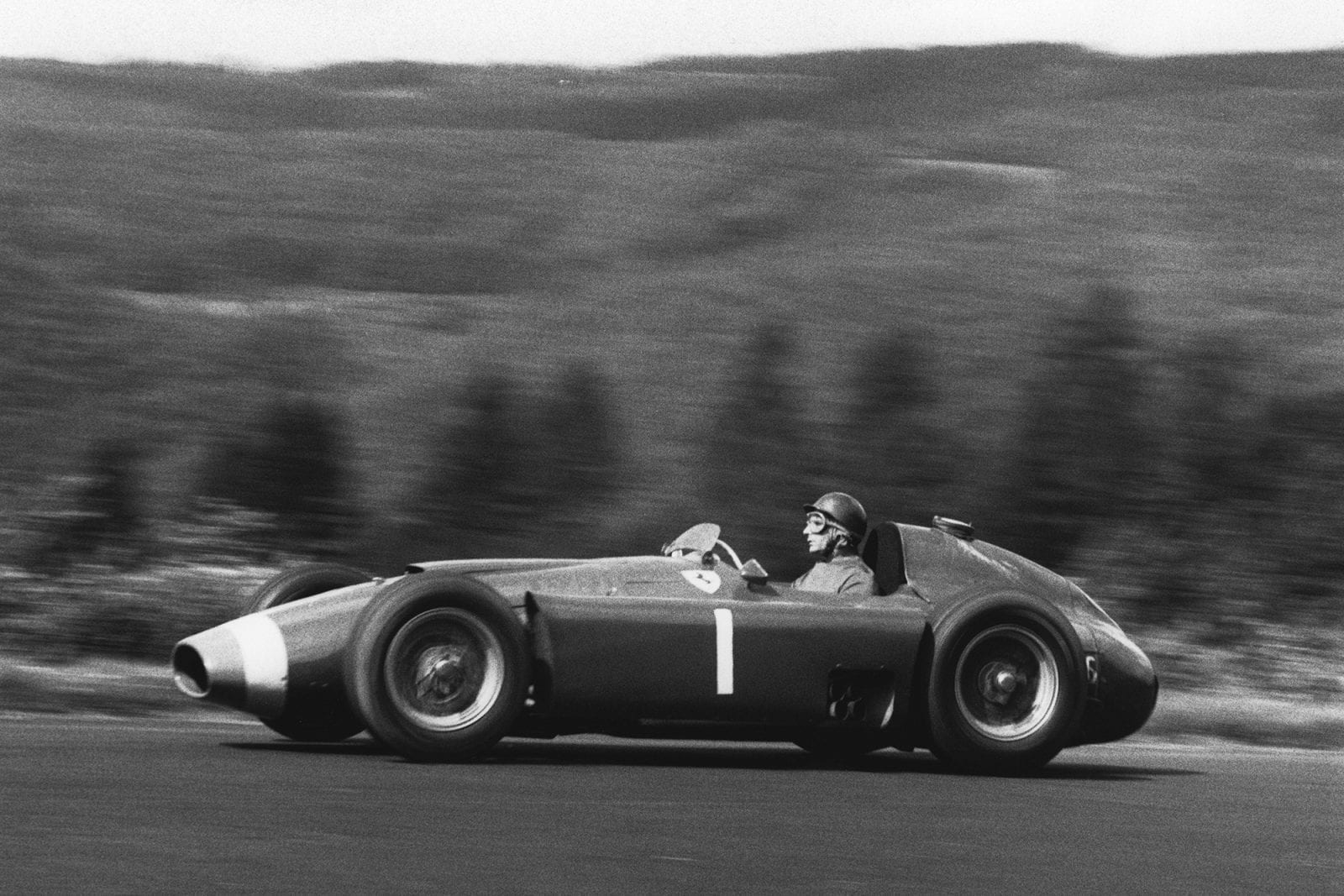

XVIII Grosser Preis von Deutschland

Juan Manuel Fangio claims his third win of the season for Ferrari and retakes championship lead

Motorsport Images

Fangio again

Adenau (Eifel), August 5th

Probably the most outstanding thing about the German Grand Prix was the fact that no British cars were entered. Not one of our Grand Prix teams made an entry which was not only surprising, but depressing as well. It was left to Italy, the real home of Grand Prix racing, to make up the bulk of the runners for one of the toughest events in the World Championship series. The Nürburgring itself is sufficient test to prove a sound car, but to race round it for 22 laps calls for terrific stamina from the drivers. Ferrari entered a full team of five Lancia/Ferraris, driven by Fangio, Collins, Castellotti, de Portago and Musso, the last-named making his first re-entry into racing since his crash in the 1,000-kilometre race back in May. All the cars were the now standard type, with small pannier tanks strapped onto the cockpit sides and the main tank in the tail, with the body spreading out the full width of the car between the wheels and having the exhaust pipes inside these hollow side pieces, and ending in four megaphones on each side. Opposed to this powerful team were three works Maseratis, to be driven by Moss, Behra and Perdisa, these all being normal carburetter 250/F1 models. Gordini entered two of his eight-cylinder cars, with Manson and Pilette as drivers, and the rest of the field was made up by private owners and private Scuderias. The Centro-Sud team entered Schell on their Maserati and Scarlatti with their old 2-litre Ferrari, while Maglioli had the Scuderia Guastalla Maserati and Villoresi was to drive Piotti’s similar car. Rosier, Gould, Halford, Salvadori, Godia and Volonterio were all driving their regular Maseratis, so that the bulk of the entry of 19 cars emanated from Modena.

There were three practice periods, all of sufficient length for new drivers to learn the difficult circuit, but on each occasion it was either raining, or the track was still damp, so that no one was able to go at all fast by comparison with the possibilities of the cars. Ferraris were having some engine bothers, and had to use the spare units they had brought along, while de Portago could not understand his slow lap times until he discovered that the back of the chassis frame was broken off. This entailed stripping all the cars for inspection and welding gusset plates around the shock-absorber mountings to prevent any further breakages. The Nürburgring is guaranteed to break up the best cars, and the Lancia/Ferraris were no exceptions, this being their first visit to the track. For a change the Maseratis were proving quite reliable and their only trouble was grounding at the bottom of some of the sharp dips, so that the front suspensions had to be set up to give more ground clearance.

By sheer luck the Lancia/Ferraris were proving the ideal cars for the Nürburgring, the handling being right for the twisty nature of the circuit, and the power and torque being in the right place, so that at no time were any of the Maseratis able to record lap times approaching those of Fangio and Collins. The old man was right on form and in spite of the wet track was hurling the car through the bends in beautiful slides, while the young man was making everyone sit up and take notice by doing exactly the same and at just the same speed. These two were easily the fastest and recorded 9 min 51.2 sec and 51.5 sec, respectively, with Castellotti third with 9 min 54.4 sec. As no one else managed to get below 10 min, it was clearly going to be a Ferrari walk-over if the damp conditions prevailed. The official record for the Nürburgring was still standing at 9 min 52.2 sec, recorded by Herrman Lang in 1939 and, though many people had improved upon this in practice and unofficial training, it had never been bettered during a race, so that the times of Fangio and Collins on a damp track indicated that the record would probably fall officially this year. Last year during an unofficial training day Fangio and Moss had recorded under 9 min 35 sec with the W196 Mercedes-Benz and the day before practice for this year’s race Fangio had been timed at 9 min 26 sec, but all this was naturally not official and could only be taken as hearsay and borne in mind as pointers for what might happen. The only driver to run into trouble during practice was Pilette who went off the road and bent the front of the Gordini and bruised his knee badly, while Piotti practised with his own car as Villoresi did not arrive until Saturday evening.

After all the damp and wet days before the race, race day itself turned out fine and dry and not too warm, and when the cars lined up on the wide starting grid in rows of four-three-four-three there were some changes to notice. The first row held Fangio, Collins, Castellotti, followed by Moss who had been practising with a pair of Maseratis, the long-nosed, high cockpit model from Spa and a brand new one, with similar long nose and ducted radiator, and he decided to use the older chassis as the new one was no improvement. This was not surprising as it was identical in design, merely being another 250/F1 car, but brand new. Behra was sticking to the car he had been using all the season, and Perdisa was to have driven a normal-bodied works car; however, in the sports-car race preceding the Grand Prix he crashed mildly and was not feeling fit so the factory car was handed to Maglioli, the Guastalla car being a non-starter as a result. The crashed Gordini had been straightened out and Andre Milboux took Pilette’s place at the wheel, making his first attempt at Grand Prix without even a lap of practice in the Formula 1 car. For the rest, everyone was present and Villoresi took Piotti’s place on the back of the grid alongside Volonterio.

Collins made a terrific start and led the field away into the first bends of the opening lap, but Fangio soon got by and led the two young British drivers, for Moss was right alongside Collins. However, the Maserati could not cope with the Lancia/Ferrari on this circuit and when they reached the straight at the end of the lap Fangio and Collins drew away. Until then they had been in a bunch and Castellotti had been trying to get past Moss, but overdid things and spun on a downhill bend, restarting again at the end of the field. Salvadori was going extremely well and holding on to Behra, scrapping for fourth place, followed at some distance by de Portago, then Maglioli, Musso and Schell in a bunch and then Halford leading the rest, which included Castellotti thrusting his way along trying to make up for his mistake. At the end of this opening lap there was the unusual sight of four cars pulling into the pits, Villoresi for a change of plugs, Manzon to retire with a broken front suspension, Gould to fix a loose throttle, and Scarlatti to repair his gear change, and when all was over and quietness descended Volonterio came touring past.

There was no doubt now that the Lancia/Ferraris were in a similar position to Mercedes-Benz in last year’s Grand Prix races, and once more it was Fangio who was in control with a young British driver sitting on his tail learning all about Grand Prix racing. Last year it had been Moss, this year Collins, and Fangio is old enough to be father of both of them. Round and round went the two cars in neat formation, though Collins was not always neat in his cornering while keeping up with his leader, and behind them Moss sat comfortably in third place, neither gaining nor losing ground. As Fangio rounded the Sudkerve, Moss appeared over the brow of the Tiergarten and it was pretty obvious that there was going to be no motor racing; merely a processional demonstration. Although this appeared dull to spectators, it was far from dull for the drivers, for the Nürburgring is one long nine-tenths dice from start to finish, even in a slow sports car, let alone a Grand Prix car, so that this was an event for the drivers and not the public, even though 100,000 of them had turned up to watch. Salvadori was sitting nicely in fifth place, but on lap three decided the engine would blow up if be carried on so he stopped and hastened away to drive on the morrow at Brands Hatch. Castelloti was down on power and stopped to complain to his mechanics, while Milhoux was having trouble keeping all eight cylinders working on the Gordini. With there being no possibility of a close race the German Grand Prix turned into an endurance feat, and on lap four Maglioli retired with his steering seized solid and Gould did likewise with rapidly falling oil pressure. Musso stopped on lap six to see if his engine was really alright and then Castellotti came in and retired, the loss of power being due to a faulty magneto. Although the race appeared to be a procession, the leaders were not hanging about and Fangio, Collins and Moss all broke the old 1939 lap record well and truly. Fangio did 9 min 48.1 sec, Collins 47.6 sec, and Moss 46.6 sec, but then on the next lap Fangio replied with 9 min 45.5 sec (140.1 kph). On this lap, the eighth, Schell stopped with his radiator boiling merrily and Halford went by into seventh place, driving remarkably well for his first serious Grand Prix. Volunterio also stopped at his pit, mostly for a drink of water it seemed. As Musso was not fully recovered front his broken arm and was not going too well, Ferraris signalled him to come in on lap nine so that Castellotti might take over. However, when Fangio arrived at the end of that lap he was alone, and Collins arrived slowly and stopped at the pit. In the general commotion that followed Castellotti was all ready waiting for Musso to arrive and did not realise that Collins was nearly unconscious and had been lifted from the car. All he saw was a red Lancia/Ferrari stopping, a driver being removed, so he leapt in, only to find he was in the wrong car, for then Musso arrived as had been planned. Collins was still nearly unconscious so that without knowing exactly what was going on Castellotti took over from Musso and rushed off. After a time Collins recovered and was able to explain what had happened; in holding the car on the starting line with the handbrake the cable had caught up on the main fuel line leaving the rear tank, and as the race progressed it chivvied its way through, the leaking fuel sending fumes into the cockpit. Smelling fuel, but hoping it was alright Collins had carried on, not realising the doping effect the fuel was having on his brain until he found himself changing from second gear into fifth gear, and bumping the edge of the road in a dazed sort of way. Before it became too late he decided to stop and the sudden cessation caused him to virtually pass out. This little drama had let Moss into second place and the inevitable Behra into third position, followed by de Portago, Castetlotti in Musso’s car, Halford, Schell and the rest more than a lap behind the leader. Lap 10 saw Fangio make another lap record in 9 min 44.9 sec, and he was a comfortable 18 sec ahead of Moss, but not really gaining anything. Halford stopped at his pit to report the loss of his twin tail pipes from the exhaust system and was told to continue on the stub manifolds while the pipes from Gould’s retired car were removed.

The pit area was still a scene of great activity, for Collins recovered remarkably quickly from his asphyxiation and at the end of the 11th lap de Portago stopped and handed his car over so that Collins might try and catch Behra. At the end of lap 13 Petite ran into trouble with a broken tank strap and a temporary repair was effected at the pit, during which time Villoresi decided he wanted to call at the pits, but seeing mechanics busy on Behra’s car be drove off again. Halford stopped to see if Gould’s exhaust system would fit, but as Maseratis are hand made, the brackets did not line up, so he continued to run on the stub pipes. While Behra was helping to fix his fuel tank Collins went by in the de Portago car, moving into third place, and then Behra was off once more before Halford appeared. Villoresi never returned to the pits, stopping out on the circuit with a broken engine and there were now only nine cars left running, for Schell had found the reason for his boiling was a broken water pump and Castellotti spun off once more and this time stalled his engine. On lap 15, with another seven to go Halford stopped to take on more oil, as the flange on the outlet pipe was leaking, and Collins in his efforts to catch the leaders overdid things on a downhill bend and spun off into the trees, climbing out unhurt but unhappy. On the next lap Milhoux was forced to give up the unequal struggle with the misfiring Gordini and Halford was given the black flag and disqualified. After driving surprisingly well Halford was lying fourth overall, a lap behind Fangio, but it transpired that he had spun out on a quiet part of the course and had been push-started by outside helpers. When he eventually stopped he was practically unconcious from the exhaust fumes entering the cockpit from the two short stubs and he had to be worked on by the medical men for a long time before he recovered, all of which was an unfortunate ending to a good first attempt on the Nürburgring.

Fangio was now drawing away a little from Moss and the gap widened to 28 sec, while the old man still broke lap records with a time of 9 min 41.6 sec and on the last two rounds Moss crossed his fingers for a horrid grinding noise started up in the transmission. In order to ease the loads he coasted round many of the corners in top gear and managed to nurse the car in to the finish, still in second place, behind the reigning World Champion and in front of Behra, these three being the only ones on the same lap. Behind them came Godia, having driven a regular steady race, but suffering from stomach sickness all the while, and Rosier a little farther back, having run a train-like race which once again paid off. So far back that he was almost out of sight came Volonterio in his old rigid-rear-axle Maserati. It had not been an exciting German Grand Prix, but certainly had been a murderous one from the mechanical viewpoint, and though Ferraris have the most potent car in Grand Prix racing at present, they are far from reliable, only one out of five finishing.

Nürburgring natters

Fangio is now 45 years old and in Grand Prix racing is still on top; after the German race he leads the Championship with 30 points, ahead of Behra and Collins with 22 points.

Behra took delivery of a nice new toy at the Nürburgring—a Porsche Carrera; he was most impressed with the wonderful finish on both outside and inside. When it is run-in he should be impressed with the way it goes.

Moss found 22 laps of the Nürburgring in a Grand Prix car one of the toughest drives he has made. The Maserati mechanics could hardly believe it possible that during practice they did not change a single engine or a single axle ratio. Missing Le Mans was a wise move.

Nice to see private-owners Halford and Gould taking the Nürburgring seriously on their first visit. Both arrived many days before practice and thrashed round in private cars, learning the way.

Ferraris also paid a pre-race visit to the track to sort out gear ratios and power curves.

The Hawthorn nonsense was badly dragged about by Press and Radio, to say nothing of Television. A pity personal animosity cannot be kept personal and not be flogged before the lay public.

After the race de Portago thought Collins should have pushed their car back on the road and continued in the race. To prove the impossibility of this they both went and collected the car and it needed Collins’ Ford Zephyr and many hands to get the Lancia/ Ferrari out of the trees. The Zephyr then towed it back to the paddock.

Among other races held before the German Grand Prix on the Nürburgring, there was a very interesting seven-lap event for 1½ litre Rennsportwagen, or racing/sports cars. This event received a more international factory entry than the Grand Prix itself and could be taken as an excellent foretaste of what the 1957 Formula II might resolve into. The Porsche factory entered four of their 1956 RS models, with space-frames, modified Spyder engines, and low-pivot rear axles, driven by Herrmann, von Trips, von Frankenberg and Maglioli. The Eisenach factory entered four AWE driven by Barth, Rosenhammer, Thiel and Binner. From Italy Maserati entered two de Dion-sprung, five-speed gearbox, factory Maseratis, driven by Behra and Moss, and Perdisa on an earlier model, and from England the Cooper factory entered two works Cooper-Climax cars driven by Salvadori and Brabham. Milhoux had the works Gordini and to make up the field there were three private owners, Hicks and Piper with Lotus and Power with a Cooper, all being 1,100-cc Climax-engined cars.

Practice had suffered from dampness, as with the Grand Prix cars, but the front row was impressive, consisting of Moss (Maserati) in 11 min 45.1 sec, Barth (AWE) 46.8 sec, von Trips (Porsche) 47.5 sec, and Behra (Maserati) 48.9 sec. Behind came Herrmann, Maglioli and Perdisa, and Salvadori was in the third row, along with the Gordini. Here were five factory cars all potential Formula II models, and when the flag fell it was the British Cooper which out-accelerated them all and led into the Sudkerve. The Gordini’s clutch burst as Milhoux changed into second gear, and the rest of the field chased Salvadori away on the opening lap. Trips took the lead, only to burst his engine, and this let Herrmann get in front, with Barth a few inches behind; then came Salvadori with Moss pushing hard to keep up, the Cooper being much faster along the straight. On lap two Herrmann still led from Barth, while Moss got past Salvadori, but could not get away and then came Maglioli, Frankenberg, Behra, Thiel, Brabham, Rosenhammer and Binner as fine a collection of mixed 1½-litre racing/sports cars as one could wish to see. On the fourth lap Barth’s engine broke and this left Herrmann an easy leader, and he made no mistakes and finished comfortably in the lead. Perdisa went off the road and Behra could not cope with the Porsches, while Moss was still being troubled by the Cooper which Salvadori was hurling about in a highly exciting looking manner, having some difficulty with feeble rear shock-absorbers. The Maserati was not running as well as it could, and was hopelessly undergeared, going to 7,900 r.p.m. on the straight and still not holding the Cooper for speed. Herrmann and the Porsche were undisputed winners, and Moss made a last lap effort to rid himself of the embarrassing little Cooper and set a new lap record for 1½-litre sports cars in 10 min 13.3 sec, a time that would have been good in a Formula 1 car. Porsche remained king of their own track, but there was a great deal of tumult and shouting going on behind them, so that they cannot rest on their laurels if they are to continue to lead the 1½-litre class.