Brawn, Jordan and Wolf – the Formula 1 newcomers that hit the ground running

Could a debutant make an instant impact in F1? It wouldn’t be the first time. Maurice Hamilton recalls the stunning arrivals of Wolf, Jordan and Brawn

Bernard Cahier/Darren Heath Photographer/Getty Images, grand prix photo

You’ve heard the words of caution. Audi, in advance of its Formula 1 arrival in 2026, is already speaking in hushed tones about needing a couple of seasons to gain a footing, never mind step onto the podium. Andretti Autosport, should it ever make it through the paddock gates, sees the subject of winning as a matter for future discussion. The suggestion of victory first time out is for uninformed optimists. And yet…

In 1977, and as comparatively recently as 2009, Wolf and Brawn turned up and savoured their respective national anthems before the debut weekends were over. Jordan came close to winning the Belgian GP in 1991 – its 11th race – only to be let down by an engine failure.

Wolf and Jordan used Ford Cosworth V8s produced in Northampton. Brawn went a few miles further, technically and geographically, by doing a deal with Mercedes High Performance Engines in Brixworth. Having off-the-shelf motors delivered in a van to the workshop doors in Reading, Silverstone and Brackley seriously reduced a worry that will have a profound effect on today’s newcomers dealing with sophisticated power units.

Audi join the F1 circus from 2026 – you’ll probably get good odds on Nico Hülkenberg taking the world title

But the increase in technical complexity behind a driver’s shoulders should not detract from Wolf, Jordan and Brawn topping – even if briefly – entry lists that, back in the day, were heavily oversubscribed. How, for instance, did Walter Wolf metamorphose from a wealthy salesman to winning entrant in the 1977 Argentine GP?

In truth, Wolf had spent a season serving a tough apprenticeship in the lower reaches of the F1 running order, largely because he found himself owning a team when, 12 months previously, such a thought could not have been further from his mind.

Born in Slovenia not long after the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Wolf’s humble upbringing prompted the search for a better life in Canada. Aged 19 and penniless, Wolf kept himself warm in cinemas and learned his English from watching cowboy movies. An astute mind and the ability to hustle would eventually earn a small fortune through setting up and equipping offshore oil rigs.

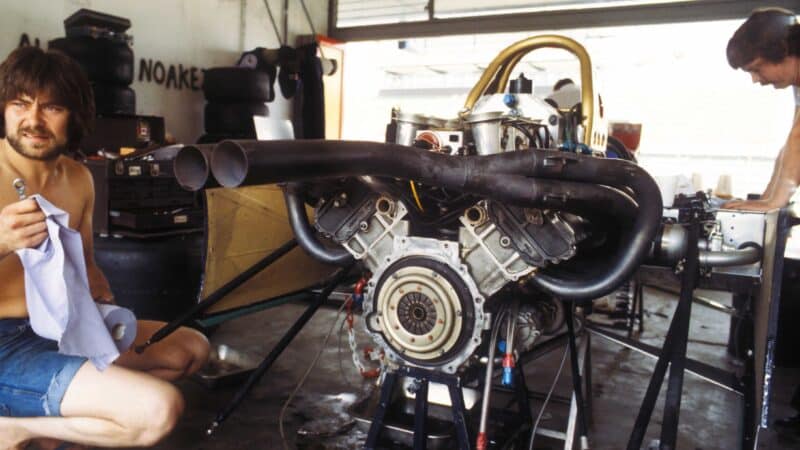

Wolf mechanics eschew team colours at the 1977 Spanish GP to work on Jody Scheckter’s DFV

Having enough money to finally indulge himself, Wolf pursued a passion for fast cars and went as far as talking to Giampaolo Dallara about running an exotic sports car at Le Mans. Dallara not only knew Frank Williams but the Italian car designer was also aware that Frank was perennially short of money – a problem which did not seem to hinder Wolf.

Invited by Williams to attend the 1975 International Trophy at Silverstone, Wolf was so enthused by the trappings of the non-championship F1 race that he offered to pay for two desperately needed engine rebuilds. Frank accepted. He had little choice, given the mounting debts which came with running a mongrel of an F1 car – sometimes two if a pay driver could be found – on a shoestring. Wolf’s fervour accelerated to such an extent during subsequent grand prix visits that he formed visions of owning his own F1 team and doing a better job than Williams. When Wolf offered to settle Frank’s debts – estimated at around £140,000 – in return for a 60% interest in the team, Williams refused.

Wolf turned his attention to Hesketh Racing. Despite a glory day earlier in 1975 when James Hunt won the Dutch GP, this small team faced liquidation. Hunt was snapped up by McLaren and Wolf accepted the offer of Hesketh’s assets (including a new car of unknown potential) for £450,000.

Having zero F1 experience, Wolf asked Williams to join him. After much soul-searching, Frank eventually agreed. But the anticipated freedom accompanying the novelty of a bank balance in the black was shackled by being treated like a gofer. For 1977, Frank Williams went off to do his own thing. The rest of that particular story would form a glorious chunk of F1 history.

Scheckter leads into Turn 1 at the 1977 German GP – a first pole for Wolf, but the podium finish kept the South African in contention for the world title

Wolf appeared to be trapped in a cul-de-sac at the end of a disastrous F1 season with the overweight and uncompetitive Wolf-Williams FW05. But the one thing he did have was membership of the Formula One Constructors’ Association (FOCA) thanks to Jacques Laffite taking Frank’s FW04 to a fortunate second place in the 1975 German GP. Wolf would never have enjoyed the associated perks and subsidised travel had he worked solely with what remained of Hesketh. But he also recognised that money spent wisely could lay the foundations for a team capable of doing the job necessary to get him out of the blind alley.

Harvey Postlethwaite may have been responsible for the Hesketh–cum-Wolf-Williams, but the young Englishman’s enthusiasm and potential was worth encouraging. Wolf was equally astute when he persuaded the efficient and authoritarian Peter Warr to leave Lotus and become team manager. This was enough to facilitate another key part of Wolf’s plan as he coaxed Jody Scheckter, a winner with Tyrrell, to take a chance with what was effectively a new team, now known as Walter Wolf Racing.

“The Wolf WR1 looked stunning, its elegant shape tastefully decked out in dark blue and gold”

When their car was rolled out of the former Williams workshop in Reading, here was final proof that this team meant business. The Wolf WR1 looked stunning, its elegant shape tastefully decked out in dark blue and gold. Postlethwaite’s creed of simplicity and reliability translated into a car Scheckter liked immediately. There may have been genuine if guarded optimism, but no one could have predicted what would happen on January 9 in Argentina, the first race of 1977.

Scheckter started from the middle of the grid, held station for several laps and began to move forward as the McLarens, Ferraris, Tyrrells and Brabhams ahead either failed or their drivers succumbed to the searing heat. With six laps remaining, Scheckter was as surprised as anyone to find himself in front and heading for a dream debut.

Argentina, January 1977 – team owner Walter Wolf with his driver, Scheckter

Getty Images

Luck may have played its part on this occasion but Scheckter would win convincingly in Monaco and Canada. With just one exception, if his Wolf was running, the South African finished in the top three. Scheckter was runner-up to Ferrari’s Niki Lauda in the championship. Walter Wolf Racing claimed fourth (out of 12) in the constructors’ championship; remarkable for a single-car entry. But that was as good as it would get. The WR5, a more complex car, simply didn’t work. Scheckter went to Ferrari for 1979 and Wolf lost interest, selling his team to Emerson Fittipaldi.

“Scheckter was as surprised as anyone to find himself in front”

Wolf may have had little knowledge of motor sport when he laid his F1 plans, but the same could not be said of Eddie Jordan. A wheeler-dealer operating by the seat of his pants, Jordan built his F1 ambition on the basic premise of, having entered a championship-winning team in F3 and F3000, GP racing had to be the next logical step. At the time (1990), Jordan’s argument was: “A good F3000 team could probably sit comfortably at the back of an F1 grid. All you need is a decent car, engine and driver.” He was soon to be disabused of that simplistic summary. But, typically, the more difficult things became, the harder and faster Jordan talked.

As it turned out, the ‘decent car’ would prove to be the easiest bit. Having used the engineering talent of Gary Anderson (a former F1 mechanic with Brabham and McLaren) in F3000, Jordan sensed a nascent designer who could pretty much turn his hand to anything. Anderson’s first job was to build a mezzanine floor and a design office within Jordan’s cramped workshop on the Silverstone estate.

Andrea de Cesaris was ever-present during Jordan’s scintillating first season in 1991

Getty Images

Finding an engine would be more difficult. The Ford V8 may have been available across the Cosworth counter but there was a limited supply. Jordan joined Coloni, AGS and Larrousse as keen customers for the DFY (latest version of the DFV). Typically, Eddie jumped the queue by going direct to Michael Kranefuss, the head of Ford’s motor sport division in Detroit. Kranefuss was sceptical. Since his primary interest was winning the championship with Benetton, Kranefuss insisted Jordan would have to accept an engine that would be one step, perhaps two, behind the Benetton Fords. At least Jordan would have the HB, a cut above the DFY.

When it came to tyres, the choice between Goodyear and Pirelli was, in Jordan’s view, no choice at all. It had to be Goodyear if he did not wish to join the other small teams struggling for grip at the back. Once again, Jordan used his blarney as he sidestepped objections from favoured Goodyear runners McLaren, Williams and Ferrari by holding face-to-face talks with Leo Mehl, Goodyear’s respected head of F1. Then EJ caused further annoyance among the big players by stealing a sponsorship deal with PepsiCo from under their noses.

An unlikely first-season world championship win arrived for Brawn at the 2009 Brazilian GP

Getty Images

Jordan’s shrewd negotiating methods received a respectful nod from Bernie Ecclestone. The de facto boss of F1 was spoilt for choice in 1991. There were 18 teams entered, some with a single car, and a total of 34 drivers aiming for 26 places on the grid. Although he would have welcomed a thinning out among what he regarded as a ragged collection of F1 newbies, Ecclestone could see that Jordan would be a creditable addition. But there would be no concessions.

Jordan had to pay for its own freight and pre-qualify for the right to practice and qualify, never mind race. The team was pared to the bone as it headed to the first race in Phoenix, Arizona. The mechanics had to carry their own kit and work to the rule: if you can’t lift it, you can’t bring it. Save for a few sponsors’ banners, the garage walls were bare. Noting that rival teams had perches at the pitwall (a comparatively new concept), Jordan constructed a rudimentary platform from scaffolding poles and planks, from where they watched Bertrand Gachot qualify 14th and hold eighth place before the engine broke with six laps remaining.

de Cesaris helped Jordan to fifth in the 1991 constructors’ standings

Getty Images

Andrea de Cesaris had failed to pre-qualify thanks to missing a gear and over-revving his V8. Despite the F1 cognoscenti scoffing at this mistake, the experienced and unpretentious Italian would turn out to be the perfect choice. Jordan went from strength to strength, finishing 4-5 in Canada with the green 191, one of the most attractive F1 cars of that or, arguably, any other era.

In Belgium, it looked even better. Apart from turning heads by giving Michael Schumacher his F1 debut, Jordan was on the verge of the impossible dream as de Cesaris closed in on Ayrton Senna, struggling for gears in the leading McLaren. With three laps to go, the Jordan retired with a blown engine. A communications breakdown had failed to notify Anderson that revised pistons would consume five times the usual amount of oil. Jordan finished fifth in the standings before going on to win four GPs and take a serious run at the 1999 title. That debut year had been propitious for a happy, hard-working team numbering 41 – in total – in 1991.

“Jordan went from strength to strength, finishing 4-5 in Canada with the green 191”

At the end of 2008, Honda Racing F1 had 700 employees. And they were far from happy. This had little to do with finishing near the foot of the championship with a dreadful car. On November 28, Honda announced its intention to quit F1. With immediate effect. It was a massive shock to the team, not least Ross Brawn who had joined a year before with plans to use his impressive championship credentials to lead Honda to the other end of the title table. Brawn had effectively written-off 2008 to focus on starting afresh for the next season. Thanks to Honda’s bombshell, his priority had shifted overnight from creating performance to avoiding redundancy.

There were several prospective buyers, most of them infatuated with the glamour of owning an F1 team without being aware of its complexities. In the end Brawn and his CEO Nick Fry reached an agreement to buy the team for £1 in return for a £92.5m budget from Honda equal to the amount the motor company would save in redundancies. Even so, 350 team members would lose their jobs.

Job done – victory for Ross Brawn at Albert Park, 2009.

Getty Images

This was on March 5, 2009. The first race in Australia was three weeks away. Getting there would be an achievement. Winning the race a fantasy not even worth considering. In the F1 season preview carried by one leading publication, Brawn GP (as the company was now known) was not even mentioned. But the guys in the Brackley headquarters knew their resuscitated team was very much alive – and quietly optimistic.

Brawn had ditched the Honda V8 and worked a deal with Mercedes for a supply of the latest version of the engine that had won the previous year’s championship with McLaren. Better than that, testing had shown their neat little car, the Brawn BGP 001, to be quick. Indecently quick.

Condescending rivals put this down to running light to attract much-needed financial backing – as witnessed by the two cars arriving in Melbourne with very little on them other than a few small sponsors, eye-catching yellow flashes and the maker’s name. But the opposition knew little about what lay beneath the virgin white surface.

Technical changes for 2009 had the intention of reducing downforce, an obstacle the team’s engineers had been preparing for during the previous 12 months. Honda’s Saneyuki Minegawa is credited with scrutinising the regulations and finding a grey area in the paragraphs defining the size and location of the rear diffuser. By creating another diffuser beneath the existing one, Brawn had effectively doubled the extraction of air and downforce in a crucial area. Toyota and Williams had also spotted the loophole. But neither of them had designed the most efficient angles for the diffuser, nor found the necessary balance in their cars, front to rear.

F1 no-marks? Despite the lack of sponsors, Brawn was the first team to win the F1 constructors’ title in a debut season

Proof that Brawn had done its sums correctly came when Jenson Button and Rubens Barrichello (both of whom had remained loyal to the team) filled the front row in Melbourne and finished 1-2. The weekend had largely been trouble-free. Which was fortuitous because Brawn had neither the time nor the resources to produce spare parts. The F1 world was flabbergasted – and quietly infuriated. Protests were thrown out, the Brawn-Mercedes being declared legal.

Brawn made the most of its advantage, Button winning six of the first seven races. Gradually, the opposition began to close in, Jenson going through a tricky period as the pressure of leading the championship for the first time took its toll. Then, realising it was now or never, Button produced a thrusting drive at the penultimate round in Brazil to finish fifth and win the championship, Brawn having already clinched the constructors’ title. Which was timely because, by Brazil, they had run out of performance and pace.

Button would move to McLaren for 2010; Mercedes would buy a 75.1% controlling stake in Brawn. The little team had become the nucleus of a big one and disappeared as quickly as it had arrived. But the mark left by Brawn GP in terms of achievement – winning both championships in a debut season – stands out, even when compared with the exceptional entrances of Wolf and Jordan.