Want to start a new Formula 1 team? It’s gonna cost you

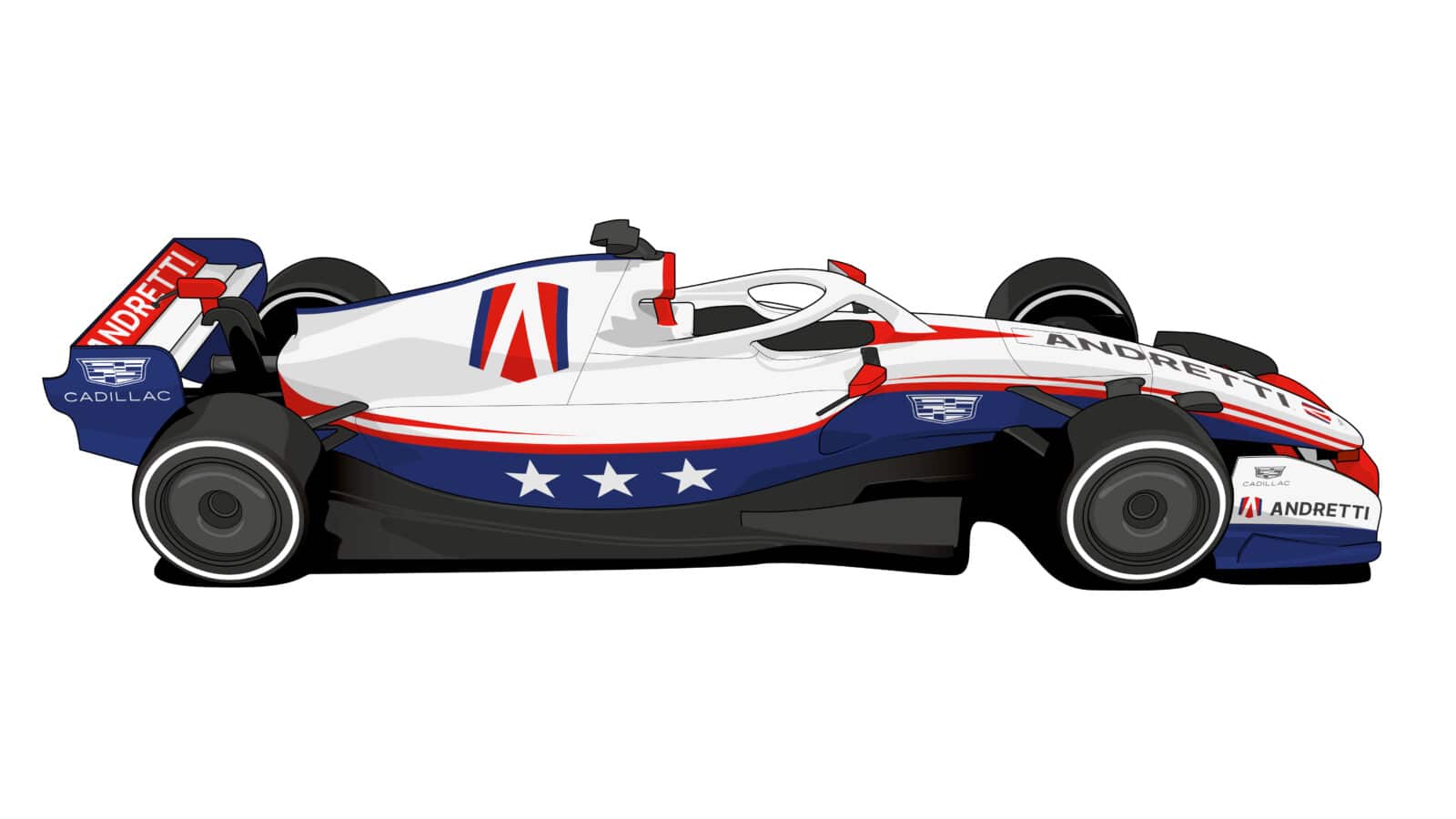

With Andretti eyeing a spot on the Formula 1 starting line, Edd Straw looks at the numbers involved in launching a new team. Deep pockets and previous success in other disciplines can’t guarantee F1 titles – or even mid-field status. Give the Americans time, though, and they might have a chance

Starting a Formula 1 team was never easy, but for decades it was achievable with cash in hand, wealthy backers or the indefatigable wheeler-dealer spirit of a Frank Williams type. Most failed, but some succeeded and those who did thrived. Today, the barrier to entry has never been higher.

F1 is typically blamed for that, with commercial rights holder Liberty Media blocking Andretti’s putative F1 team despite the FIA accepting it. Even if Andretti Cadillac had been allowed in, what’s often referred to as the entry fee, actually a $200m ‘anti-dilution’ payment to compensate for the fact that the share of F1’s revenues taken by the teams would be split 11, rather than 10, ways seems ludicrous. But it’s a drop in the ocean compared to what it takes to start from scratch. Mercedes team principal Toto Wolff has suggested that “you need around $1bn” to do so credibly.

Existing owners are hardly impartial given the desire to protect their own businesses. F1 acts as if it runs to a franchise model, which is not the case with the rules allowing space for six more cars and the Concorde Agreement permitting 12 teams, but as Williams boss James Vowles said in explaining his opposition to Andretti’s entry “it’s not that we’re close-minded to more people coming into the sport, but what we’re very careful on is protecting the sport we have right now”. However, doubts about new teams are not solely based in self-interest, for F1 teams are complex beasts.

Take Williams as an example. It’s currently F1’s ninth-best team but recently hit 1000 employees. Sauber is last and employs over 600 and expects to have around 900 by the time it becomes Audi in 2026. The days when a small team could even run a car, let alone design and build one, are long gone. The performance needed even to be at the back is enormous. The slowest team of 2024 – Sauber – is within 1.9% of the pace. Wind back 30 years to 1994 and that deficit would put you fifth-best.

“The challenge of creating a new power unit is itself a costly project”

F1 teams today are self-contained industrial complexes, requiring not only specialist personnel but also state-of-the-art machinery. Say you want to build your own factory with wind tunnel, driver-in-loop simulator and the bewildering array of other specialised machinery required – the capital expenditure required is astronomical. Aston Martin puts the cost of its new Silverstone facility at around £200m. And if you want the quality and speed of turnaround to be sufficient to be competitive, you need the best kit in every area, from composites manufacturing to design tools to additive manufacturing to shaker rigs… the list is endless.

Suppose you have a top-line factory and facility staffed with 800 proven, accomplished F1 personnel. Now, you must design and build a car. The only extant start-up team of the 21st century, Haas, gained its foothold through a Ferrari technical partnership that gives it a lot of the nuts and bolts needed to make a car – effectively it ‘only’ has to produce the monocoque, aerodynamic parts and a few other specified components. A new team today wouldn’t be allowed in on that basis. It requires vast knowledge to produce all of that in-house, often stretching to developing proprietary technologies and processes that can’t be bought off the shelf. Creating that from scratch takes years.

Making a go of a new team in F1 is close to impossible. However, a suitably ambitious team with the right lead time, resources and leadership could make it work. If you’re prepared to commit $1bn-plus – and that ‘plus’ is doing some seriously heavy lifting as Wolff’s estimate is, if anything, conservative – then it is possible to turn up and run credibly with time. There are also some advantages today, such as the fact that while once upon a time newcomers might be saddled with old-specification engines, F1’s regs mean you are guaranteed a good level of powertrain performance. There are also open-source parts whose design every team must share with rivals and the potential to buy some parts from a rival even if not to the extent of Haas. However, with F1 keen only to let in OEMs, there’s the additional challenge of creating a brand new power unit – itself a massively time-consuming and costly project.

Andretti is adamant it can succeed, with big-bucks investors and the might of General Motors behind it. It has already sunk vast sums into its F1 team in the expectation that, eventually, F1 will be forced to relent. But even a well-funded team with a long lead-time is expected to start off at the back – and probably well off it. To make it work will demand as much patience as cash, perhaps even more.