The man behind Goodwood’s Festival of Speed sculptures

The huge sculpture on the Duke of Richmond’s front lawn has become an essential element of the Festival of Speed. Adam Hay-Nicholls meets Gerry Judah, the creative figure behind the awe-inspiring Central Feature design

The 2015 sculpture featured the Mazda 787B and LM55 Vision Gran Turismo

Getty Images

Gerry Judah’s rolling art commission at Goodwood’s Festival of Speed began in 1997.

Dayydd Jones

Most of the machines one finds at the Goodwood Festival of Speed are designed with singularity of purpose: to go as fast as possible. The clue is in the name. But, emotionally, the vehicles that tear up the Duke of Richmond’s driveway are about so much more than sheer velocity. Their focused designs carry hopes and dreams beyond the ambitions of the pilot sat in that snug, spartan cockpit. Racing and performance cars are built to inspire, and the Festival of Speed exists to celebrate this and put thoroughbred racers and slinky sports cars on a pedestal of worship. And, just as a cathedral has a tower so as to be seen from a great distance, Goodwood has an automotive sculpture designed to draw followers and act as its festival centrepiece.

Each year, Goodwood has a featured marque; a manufacturer with its own disciples, perhaps due to its style or success on the track, often both. This time, it was Porsche taking the spotlight, in the year of the carmaker’s 75th birthday. They supplied the candles, and Gerry Judah baked the cake.

Judah, 72, is the artist responsible for each year’s Central Feature; pieces of towering symbolism that started in 1997 with a triumphal arch capped by a sculpted prancing horse and with Michael Schumacher’s Ferrari F1 car hanging underneath. This was the fifth edition of the fledgling FoS, and the Earl of March, as Charles Gordon-Lennox was styled at the time, wished to commission something almost theatrical to toast 50 years of Ferrari. The heir to the Goodwood Estate had been a commercial photographer working in London in the 1980s, which is when he and Judah first crossed paths.

Gerry was born in India in 1951. His mother was from Calcutta, his father from Rangoon, and the family emigrated to London in 1961. Other profiles have cited Judah’s memories of the West Bengali landscape, the rituals, the awesomeness of the mosques, the grandeur of the temples and synagogues of his childhood being the spark for his oeuvre. He’s rather dismissive of this. “That’s the legend, print it if you like… A lot of things drive you. India had visually exciting things to see, and there was no television. It all feeds into what you become. Coming to London in the 1960s was incredible too. Doing well at school; that drives you as an immigrant. And there was this cultural explosion. From the ’60s, through the ’70s and ’80s, London was the place to be. It gave me an education, a place to live, a future, a family, and the biggest thing of all; opportunity. Opportunities are very hard to come by these days. It was a great place to start out then. There was a palpable energy.”

Forty years of Honda GP success, 2005.

In 2019, the FoS marked 70 years of Aston Martin at Goodwood.

Alamy

Steel tubes for the E-type 50th anniversary, 2011.

Alamy

Off-roading reference for Land Rover, 2008.

Lotus 60th anniversary, 2012.

Alamy

St Paul’s WWI memorial, commissioned in 2014.

Roman arch – Ferrari, 1997.

Judah’s Inspiration 911 stands outside Porsche’s Stuttgart base.

Getty Images

Littlehampton Welding has fabricated and installed FoS sculptures since 2004

Fifty years of Toyota’s involvement with motor sport, 2007

After graduating with a double-first in fine art from Goldsmiths College and an MA in sculpture from the Slade, he established a studio on Shaftesbury Avenue in 1977 and made a name for himself in theatrical and commercial set design, working for the Royal Shakespeare Company, the English National Ballet, the National Theatre (his props shared the stage with Rudolf Nureyev, Judi Dench and Ian McKellen, to name a few), and later with the groundbreaking advertising agencies of the day – Saatchi & Saatchi and McCann Erickson – building models and backdrops for brands such as Greenpeace, Heineken, Smirnoff, Silk Cut and Benson & Hedges, and collaborating with photographers including Terence Donovan, David Bailey and a young man known as (Lord) Charles Settrington – aka Charles Gordon-Lennox, later the 11th Duke of Richmond.

“London in the 1960s was incredible. It was the place to be”

“We were both young guns then,” beams Gerry, “and there was a renaissance in advertising in the ’80s. We were constantly being challenged by new ideas and directions. We were used to working to tight deadlines and budgets, and expressing concepts concisely and quickly – because you ain’t got time. For one client, I made a whole city of biscuits for a biscuit commercial. I had boxes and boxes of biscuits. I got a band-saw and built cathedrals out of them. Another campaign required me to make complicated Swiss clocks out of Swiss cheese, which was really resin. There wasn’t a computer in sight.”

In 1992, interest rates went through the roof and the ad industry came crashing down. “Yuppies were sleeping in their BMWs.” Fortunately for Judah, there were lots of other projects to get his teeth into, such as creating the contents of the Spanish Pavilion at Expo 92 in Seville, which led to working on the Magna Science Adventure Centre in what was Rotherham’s steelworks, the Millennium Dome and many other Millennium projects – and this revealed a talent for pulling teams of engineers and industrial craftsmen together. He also won over musicians, working on video projects for Paul McCartney and Led Zeppelin, and he designed the scenic backdrops for Michael Jackson’s 1996-97 HIStory World Tour.

They’d not seen each other in a decade when Charles picked up the phone in 1997 and invited the artist to create a shrine to the Scuderia. “Despite terrible rain and winds to endure when we put it up, it was great fun and a few months later he asked if I wanted to do another.”

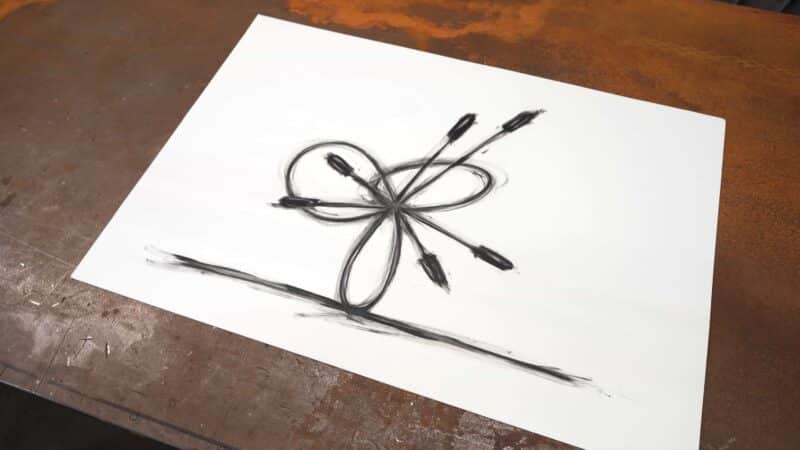

A sketch of Porsche’s FoS 2023 feature

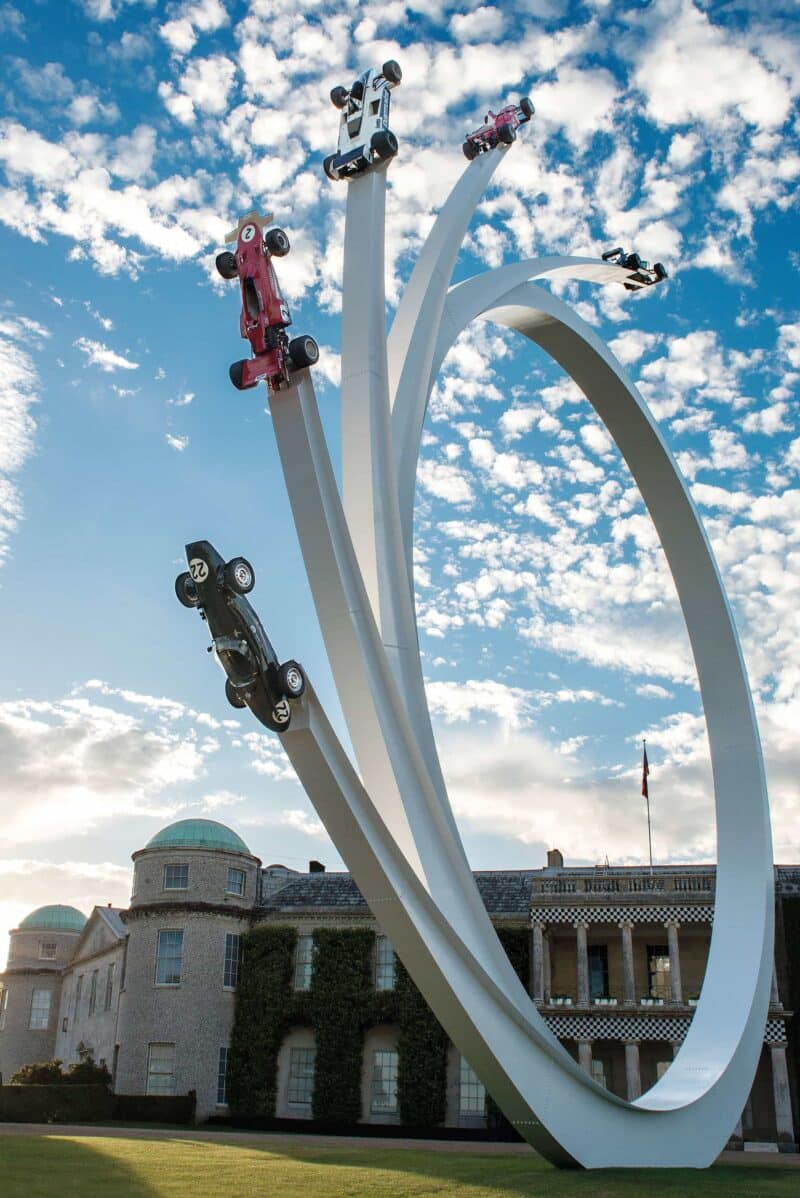

The finished sculpture, celebrating the 75th anniversary of Porsche’s first sports car

Since then, Gerry’s Goodwood works have become increasingly bold and ambitious. There have now been four Central Features dedicated to Porsche (1998, 2013, 2018 and 2023), two to Audi (1999, 2009), Jaguar (2000, 2011), Mercedes (2001, 2014), Renault (2002, 2006), Lotus (2012, 2021) and BMW (2016, 2022), one each to Ford (2003), Rolls-Royce (2004), Honda (2005), Toyota (2007), Land Rover (2008), Alfa Romeo (2010), Mazda (2015) and Aston Martin (2019), and a sole tribute to a motor sport individual – Bernie Ecclestone (2017). I’ve come to meet Gerry at his studio in Harringay, North London. I was expecting a huge warehouse, given the size of some of his works, but this is no bigger than a living room, with a paint-splattered desk, plaster-caked chairs, beautiful ink drawings stacked away, and small-scale sculptures and models that are the starting point for something much bigger – often involving three engineers and 40 fabricators. He proudly shows me a 12in-tall model of his next major commission – a blue splashing drop of water that’ll be 21m tall and destined for the Calgary TELUS Convention Centre in Canada.

“We were worried the Mercedes might get struck by lightning”

“I never go into what these things cost,” Gerry cautions, “but it’s about making sure those paying for it get a happy reward.” For each commission, he’ll make hundreds of sketches, and then he’ll manufacture a couple of models. “I know it can be built before I present it to the client. I know it’s within budget, and I know we can make it on time.” When it comes to the Goodwood Central Features, there are always two clients – the Duke and the marque. “They’re already on board – they’ve signed up to do it. They’ve seen what I’ve done before and they trust me. I usually present two or three different ideas to give them a choice, but I know which one I want to do. When I did BMW, I flew out to Munich for a 6.15pm meeting with the directors. Within 20 minutes of taking the model out of the box, they’d approved it and I was on my way back to London.”

He describes his task as, simply, “finding different ways of displaying cars. But I like the concepts of engineering and sculpture to be strongly present. I don’t do mood boards or anything like that. I put a model on the table and say, ‘This is what I can make.’ I’ve never had an automotive client that’s been difficult.”

Indian childhood inspiration in his 2020 solo exhibition Bengal: The Four Elements

His plans are sent to steel cutters in Italy, Amsterdam and Durham and, in the case of the FoS features, are fabricated by an architectural welding company on the West Sussex coast, just 13 miles from Goodwood. The sculpture is delivered as a kit of more than a dozen parts, occasionally under police escort, which is then installed by an experienced ground team.

It must be daunting, erecting often priceless cars 10 storeys in the air, for the crew, for the artist, and perhaps most of all for the marques, collectors and museums that have lent them. “It requires a huge level of trust,” acknowledges Gerry of the effort as a whole. “Everything up there is original, because that’s the whole idea of Goodwood. These are the original racers and they project that spirit. We could have stuck the cars up on podiums as you might in a museum, but that wouldn’t give the cars the salute they deserve. You need some element of danger and panache, as exhibited when they’re racing on the track. You need some derring-do.” The cars are held in place by their wheels, which sit in specially designed cups and are strapped to them tightly. “We treat each car very delicately.”

He beckons me over to his computer and clicks on the plans for this year’s Porsche salute, for which he drew the first sketch last Christmas Day.

A model of the selection ramp at Auschwitz was part of the Imperial War Museum’s Holocaust Exhibition.

The 75th anniversary sculpture comprised 16 pieces in total, which were bolted together and erected on the Goodwood lawn in July. It had a dodecahedron at its core, with its 12 points intersected by six dynamic loops. Flying out on these huge steel arms were six cars, some new, others historic: a 1950s Porsche 356; a 712 Formula 2 car; the latest 911 Carrera GTS; the 962 Blaupunkt that raced at Le Mans in 1990; the brand new £214k 911 Sport Classic; and Stuttgart’s LMDh contender, the 2023 963.

“Are those good cars? I don’t know,” shrugs Gerry. “I’m not really a car guy. I love car design. The Corvette Sting Ray – I loved that in the ’60s. And I’m blown away when I see these amazing machines at Goodwood. But I maybe don’t have the relationship with cars that people who come to Goodwood do. If I didn’t have that distance I don’t think I’d make the sculptures that I do.”

Of all the Central Features he’s done, he picks his 2011 E-type sculpture – a vast 175-tonne 28m-high fixed-head-coupé Jag made from steel piping that pointed at the ground – as his favourite. “I know it’s not everyone’s favourite, because it looks like a load of tubes. But it was a concept that worked well with the curviness of the car, and I liked it as a pure piece of sculpture. I also liked the Porsche one in 2018 [which was 52m tall], because we managed to bring that sculpture down to a point no wider than a coffee mug. And the Mercedes [300 SL Gullwing, in 2001] that went over the house. That was so crazy. We were worried it might get struck by lightning! They all have their qualities about them.”

the 2017 Festival of Speed centrepiece was dedicated to Bernie Ecclestone

Judah is clear, though, that he doesn’t wish to be defined by these works. “The Goodwood sculptures have started to define me, and I’m not very happy about that. It’s just one of many projects that I do.” Among them: two large cruciform sculptures displayed at St Paul’s Cathedral to commemorate World War I; the Scroll at Sharjah, UAE, which was the UNESCO World Book Capital in 2019; and a highly detailed model of Auschwitz’s ‘selection ramp’ which was part of a holocaust exhibition at the Imperial War Museum. “I love doing those. They’re not any better or worse than the car sculptures, but they tell a different story.

“It’s almost unconscious how I approach sculpture. I don’t do brands. None of the sculptures I’ve done for Goodwood have spoken about the brand. You can get an advertising agency to do that. I do something more intuitive. It is, dare I say it, a spiritual journey in design.”

Gerry credits the Duke with keeping the process of making the FoS features fun. “We’ve kept that energy we had in the ’80s going. He’s willing to take risks, and I can’t go and give him a rehash of an old idea. It’s the client that makes a great piece of art, not the artist. And Charles is a pretty damn good client.”