Driving Jaguar's wildest car: XJR-15 on the jagged edge

History hasn’t been kind to the reputation of Jaguar’s short-lived XJR-15 road racer, but is it all that bad? Andrew Frankel heads to Donington Park to find out first hand

Jayson fong

I knew I’d be busy, but not this busy. I’m at Donington, one of my favourite circuits, the weather is perfect, the track inexplicably quiet for an unsilenced test day. No better place, no better conditions in which to get to know one of the most enigmatic sports racing cars there has been, an important car for reasons we will get to and, it is fair to say, a car with a certain reputation. And right now, it is earning every mote of my attention.

In the beginning it was never going to be called the Jaguar XJR-15. It would have been the TWR R9R, but then Jaguar weighed in through the JaguarSport company it owned with Tom Walkinshaw, and the XJR-15 it became. That was 1991 and it is a car about which quite a lot has been written, a considerable amount of which is rubbish. Probably the single largest nugget of misinformation about the car is the contention that the road cars were little more than the race cars wearing number plates or, conversely, that the race cars were just road cars on slicks. This is cobblers. They had different tunes for their engines, chassis and completely different gearboxes. There’s also the small matter of a 200kg difference in weight.

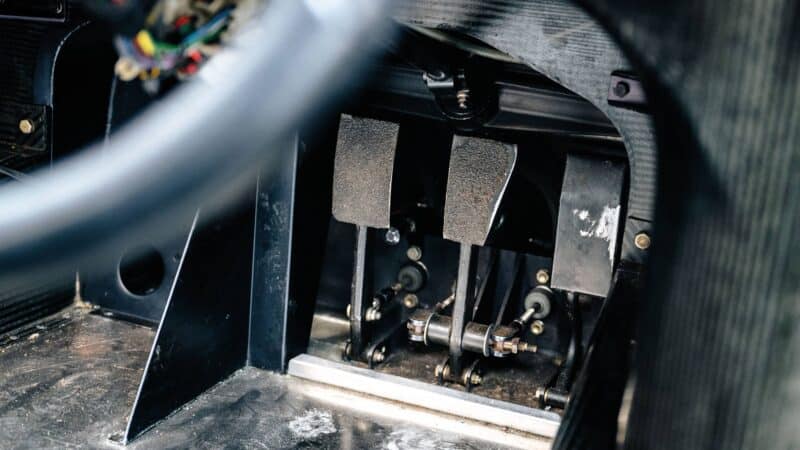

Swathes of carbon everywhere you look. The interior is more Group C than supercar.

Slumbering V12

Jayson fong

People get the number of cars wrong too: there were meant to be 50 but in the end 53 were built, of which 18 were racers, not 16 or 17 as you can read elsewhere – the illusion on an extra car being created because chassis 13 was omitted. But of those 18 just 16 were used in the famed three-round one-make race series for which they were created and two were spares. But a number have since been turned into road cars and three used for the XJR-15LM project to create a Le Mans eligible car, so the number of racing XJR-15s today that are as they left the factory is in the single digits.

But all that aside, what is this car and why is it important? Here we have also to correct the record, because if you ask most people to name the first carbon-fibre road car, some will say the McLaren F1, others the Ferrari F40. Both are wrong. The F40 was a car whose entirely conventional steel spaceframe was merely clad in part with carbon. And the F1 came after the XJR-15, which was actually the first car registered for the road by a recognised manufacturer with a genuine carbon-fibre (mixed with Kevlar in this case) tub.

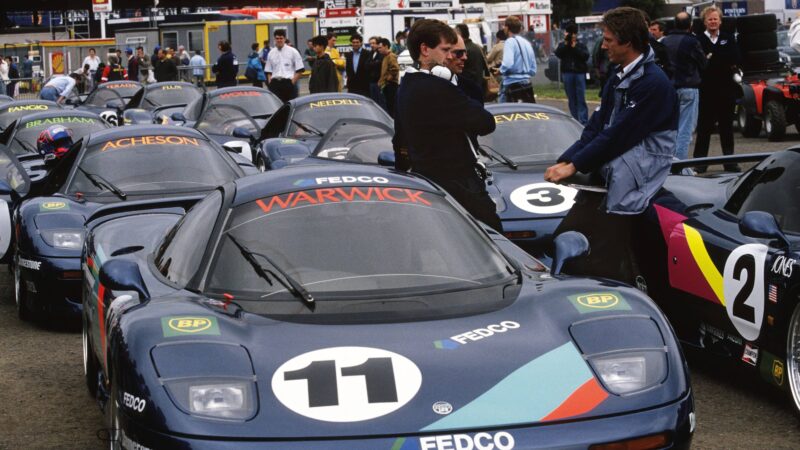

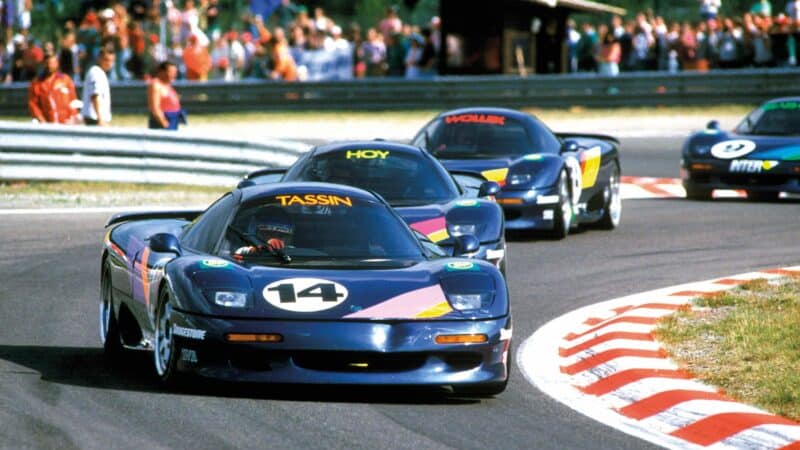

While only a handful of races were held, big money prizes attracted some star drivers

Grand Prix Photo

Unsurprisingly, it was conceived by Walkinshaw in the late 1980s not only as a way to make money, but also to show Jaguar how a proper road-racing supercar should be done. Jaguar was at the time working on its own car, the XJ220, and while TWR would also become instrumental in that car’s development, at the time the two projects were entirely separate entities.

“It was conceived by TWR to show Jaguar how a road-racing supercar should be done”

It is worth remembering how the world was back then, riding out the final stages of the ’80s bull market as it was. So many new supercars were conceived – the Jaguars, the Bugatti, the McLaren F1, Cizeta-Moroder and plenty more; few would have predicted that the only thing they’d go on to have in common was their commercial failure. All except perhaps this one. And where TWR was smart, far smarter than Jaguar and all the above named, was to do a Blue Peter on it and base it upon something it had made earlier.

That something was the series of Tony Southgate-designed, V12-powered, carbon-tubbed Group C cars, the XJRs 6, 8, 9 and, eventually, 12. The tub used for the XJR-15 was near identical to that which had won Le Mans in 1988 at the heart of the XJR-9LM and came with its suspension systems too. But the powertrain was distinctly different. It was of course still the same single camshaft per bank, two valves per cylinder engine designed by Wally Hassan in the 1960s, but instead of the full-house 7-litre, 700bhp race motor, it displaced a mere 6 litres and was claimed to have an almost sensible 450bhp. That figure, however, is debatable to say the least where the race cars were concerned which had different camshafts, different timing for ignition and engine, and different ECU mapping. If you told me the race engines pushed out closer to 500bhp I’d not be remotely surprised. The transmission was a six-speed Hewland dog ’box, which I understand was developed for the XJR-12 but deemed surplus to requirements when chicanes were installed on the Mulsanne Straight, cutting the range of speeds the gears had to cover by over 30mph. It retained the old March-designed five-speeder instead. Street XJR-15s used a five-speed ’box similar but not identical to that used in the XJ220.

Jayson fong

The Jaguar Sport Intercontinental Challenge raced only at Monaco, Silverstone and Spa… hardly ‘intercontinental’.

Jayson fong

Road tyres were less than ideal

Jayson Fong

The body was another classically beautiful, clean and shapely Peter Stevens design, pre-dating his work on the McLaren F1. As for aerodynamics, there was a rear wing which looks like it would make almost no difference at all, a modest front spoiler and rear diffuser whose efficacy would have been seriously compromised by the distinctly un-Group C amount of ride height the cars would run.

Inside, the cockpit is racing-car cramped, far less spacious than that of the XJ220, with simple analogue dials showing volts, oil pressure and water temperature arranged either side of a conventional tachometer and, strangely for a racing car, speedometer. What there isn’t is any kind of fuel gauge. Apparently the road cars had a light that came on when petrol levels got critical.

“This car is about to be driven at something close to anger for the first time in 20 years”

You sit hunched forward, not laid back as you might expect. Remember the tub was designed for a Group C car with full ground-effect aero and no power assistance for the steering so you’d need to have your hands quite close to your chest just to have the strength to turn the wheel and survive a stint at a high-downforce track.

This car bears the legend ‘001-RACE’ as its chassis number, the first of the competition XJR-15s, owned and driven by music mogul Matt Aitken in the first two rounds of the JaguarSport Intercontinental Challenge at Monaco and Silverstone. At the final round at Spa-Francorchamps, the winner-takes-all, million-dollar race, the late David Leslie was drafted in to drive the car, coming home in seventh place behind the now rather wealthy Armin Hahne.

Today the car is at Donington and, as its owner points out, about to be driven at something approximating anger for the first time in at least 20 years. I’m a little nervous, not because I made the mistake of watching Jeremy Clarkson drive one and pronounce it “the worst handling car of all time” but because I’ve seen on-board footage of Tiff Needell driving one at Silverstone and it’s about as wild a ride as a far more brave and talented man than I would want to have in a car. So I took the liberty of giving him a call.

“Really, it was a terrible car,” Tiff recalls, his mind winding back over 30 years as if it were yesterday. “That heavy engine, a high centre of gravity, zero aero… The tyres would take about three laps of that engine swinging about and then simply disappeared. No wonder at all so many got crashed. The cockpit was incredibly hot and the privateer cars like those I raced were all half a second slower than Tom’s cars…”

“Its voice is urgent, fabulously mechanic and played across several octaves… It’s electrifying”

I ask him to sum it up in a couple of words. Tiff pauses then says, “Brutally awful. Sometimes you drive a car and it’s bad but in quite a fun kind of way. It wasn’t even that.”

The XJR-15 has been brought here by the fine folk of Bell Sport & Classic through whom the car is to be sold, and the first thing I note is that, despite this being a race spec XJR-15, it is nevertheless wearing a number plate. I am told I can drive it on the road if I like, which means only one thing: it’s on street tyres. My heart rate takes another flight of steps towards my mouth in a single bound.

But at least I’m comfortable in here. I’ve elected to drive without a seat and am instead tied down by race harnesses and supported by the boys from Bell Sport’s artfully constructed foam padding. I recognise the bank of switches you must flick to fire it up, because you find exactly the same ones in the cockpit of an XJR-9. Pumps, ignition, starter, bang! The V12 fires at once. It’s unsilenced and while I’ve been told I needed lots of ear protection, I’m quite glad I forgot. This thing at full chat is going to sound incredible.

There are no requests from the owner other than that I should drive it hard enough to understand it but to respect its value, scarcity and history, which sounds fair enough to me. Don Law has recently rebuilt the engine so I won’t have to worry about that, and while there is no redline on the dial, Tiff talks about a 6200rpm limit on the video, which seems about right to me. It’s time to go.

Feels good at first. My initial concern is the gearbox of which I’ve been asked to take particular care. The March ’box in the Group C Jaguars is some distance from my favourite of its kind, but actually this one is easy, you just have to make the swift, positive shifts it demands; you’ll only damage it by trying to be gentle. The engine is a marvel too. I’m not quite sure what I was expecting but its manners bear no relation to its sound at all. The latter is beautiful but absolutely ferocious, the former as charming as can be. Relieved of the need to provide vast amounts of top end power, it instead pours on the torque from around 2500rpm, providing a solid wall that builds as you near your self-imposed redline. Its voice is urgent, fabulously mechanic and played across several octaves, all at the same time. The throttle response is electrifying.

So much for straight lines. I’m expecting the corners to present a different kind of challenge so, for what I hope are clear reasons, I approach them quite gingerly at first. The brakes are fine: it still has its original calipers but Don has rebuilt them and the pedal feel is strong and consistent. The steering is race-car quick, as you’d expect, but aims the car precisely wherever you want it to go. I start to wonder if it deserves its reputation after all. As I up the effort level I force myself to remember its riding on Pirelli road car tyres, because in a car this fast, stripped out and loud the instinctive part of your brain still assumes it’s on slicks.

Careful on the right pedal if you’re not on a straight.

Jayson Fong

The rear wing is wonderful, but adds little

Jayson Fong

I wonder too whether the same brain is not playing another trick on me. Because its cockpit is so redolent of the XJR-9 and because it sounds like an XJR-9, perhaps there’s a subliminal part of me that expects it to handle like an XJR-9 too. And even that car, with all its downforce, is sufficiently difficult for it to be easy to understand why, unlike rival Porsche, Jaguar never made a customer version. You have to be quite careful accelerating away from slow corners in a Group C Jag, when the full body aero is at its least effective, and even more careful braking into them because you don’t really want that enormous V12 going on manoeuvres. In the quick stuff you’re blanketed by all that lovely downforce, but in the XJR-15 that’s an attribute notable only for its absence.

There is no downforce, or certainly none I could discern. It also seems to be set up quite softly so the car doesn’t so much flick into the apex as gently roll, which actually feels quite nice when you’re not going for it. But even without driving it fast, you can see this might prove problematic later on and that whatever problems it had on slicks are likely only to be exacerbated on treaded, road-legal rubber.

But I can’t just stooge about all day. A few fast laps are required, so I hammer down to Redgate, thrilled by the noise, the speed, the quality of the gearshift, the closeness of the ratios and that nice, firm brake pedal. But as I turn in there is no reassuring stabilising understeer; on the contrary there’s a slightly queasy sense of roll-induced oversteer, nothing serious so far, but enough for what little trust you may have had in the machine to disappear out of a Plexiglass side window, never to return. It’s more predictable once you’re back on the power and traction out of slow corners is better than expected given the tyre limitations, so it’s not as if that softness and weight at the rear is entirely without advantage.

Thierry Tassin in action at Spa’s million-dollar race, the last XJR-15 event

Getty Images

Speedos are rare in racing cars such as these

Jaguar XJR-15

But driving a car like this, especially one with something of a reputation, is all a matter of building confidence, and it’s hard. It’s the opposite of a silent assassin, one that gives every impression of being your best friend until it turns round and mugs you. The XJR-15 makes no bones about it. It likes you no more than you like it and if it can make you look like a total idiot, or worse, it will be its pleasure.

There’s a bit of me that thinks I’m half the problem; that if I’d come to this car with no prior knowledge of its history, I’d take a different approach. I’d realise it was a little unruly and respond in kind with a firm hand, taking no nonsense from it, bending it to my will. But this is not my car, its value is measurable in the millions and I’m not here to prove a point.

“Is its next owner really going to be too concerned if their XJR-15 is lairy on the limit?”

I do some more laps and discover that if I drive it like an old 911, conservative on entry and early on the power there’s real fun to be had, but every time I up the effort level it feels like it wants to bite. And, just once, it did. I was approaching the Craner Curves where you transition at speed from right to left. And as I eased it over to the left I was aware of this huge pendulum motion behind me as the V12 investigated the possibility of making the car go sideways as well as forwards. It was enough, at least for me. I drove slowly back to the pits and climbed out for good.

It was an experience I enjoyed more for having done than while doing it. And yet the car still fascinated me. Broadly speaking racing cars are easier to drive than you might imagine – often far easier than their road-going equivalents – because going around tracks fast is what they’re designed to do. And part of the trick is to make them sufficiently user-friendly for the driver to be able to get the most from them. Because all the horsepower and grip in the world is pointless if the driver lacks the confidence to use it. I guess because it was intended only for a one-make race series and never to be competitive against a rival manufacturer’s product, such considerations were simply not relevant to TWR.

Forget the seat: our Andrew settles into a makeshift foam insert for extra space

Jaguar XJR-15

Even so I’d like to have driven it on slicks too, and perhaps a day after someone who really knows these cars had set it up to be as good as it can be. I’d want it lower and stiffer for a start. Because for all its limitations, I’ve a suspicion it wouldn’t take much to unlock the true potential of the XJR-15, and then it could be incredible. Right now it feels a little like a caged lion, an extraordinary animal captive within the limitations of its chassis. Or maybe it just needs a better driver, someone who’d back himself to tame it to the point where he’d be unafraid to put his head in its jaws. Because for me one snarl was enough to make me head straight for the exit.

But does any of this actually matter any more? Is its next owner really going to be too concerned about their XJR-15 being lairy on the limit? Or will he or she simply revel in its beauty, its sound, its rarity and its heritage? I think the latter. For simply being one of fewer than 10 racing versions of the world’s first carbon fibre road car, its place in history is assured. And as an occasional thing to drive on the right road, in the right conditions and to unleash in a straight line, it would thrill like few others. For that it probably has an appeal which simply didn’t exist when it was new. I’d just keep it away from the race track.

Our thanks to the XJR-15’s owner, Bell Sport & Classic (bellsportandclassic.co.uk), where the car is now for sale, and Donington Park.

Specification

Production: 1990-92

Power: 450bhp

Engine: 5993cc, V12

Weight: 1050kg

Max Speed: 191mph