Howden Ganley: The Motor Sport Interview

He claims nobody remembers him as a racer, but as one of the sport’s formative Kiwi innovators, he became a lynchpin of some of the finest teams

Mcklein

Howden Ganley came to England from New Zealand in 1962 and, having won races back home in his own Lotus 11 he set about achieving his ambition to climb the ladder to fame and fortune in Europe. This took him longer than anticipated but in 1964 he got a call from Bruce McLaren and was one of the first four people, all Kiwis, to join the expanding McLaren team. He started as a fabricator, graduated to mechanic, and stayed three years before leaving to focus on his desire to race. In 1967 he got himself a Formula 3 Brabham BT21, along with a van and trailer, and took the first step up that ladder. Not only did his talent and determination take him all the way to Formula 1, with BRM, Williams, March and Maki, but he came second at Le Mans for Matra and later partnered with Tim Schenken to become a manufacturer with Tiga Race Cars. Lucky to survive two huge accidents at the Nürburgring in 1973 and ’74, Ganley has remained closely involved with the sport as a director of the BRDC and has written a lively autobiography, The Road to Monaco, which captures the ups and downs of a long and varied career.

Ganley aboard his McLaren M10B in F5000 back in 1970. He would finish second in the championship to Peter Gethin

Mcklein

Motor Sport: You were racing in New Zealand, winning some prize money, so why did you make the move to England with no prospect of a job?

HG: I wasn’t doing well enough to make a living. I’d done some journalism because my parents considered that qualified as a “proper professional job” but I didn’t see myself as a journalist. I wanted to be a professional racing driver. I could stay in New Zealand and be a big fish in a tiny pond or go to England and be a small fish in a big pond and swim my way to the top. My grandfather died, in a rather timely manner, and left me enough money for a one-way flight to Sydney, then a rusty old boat to Piraeus and a bus overland to London, arriving on a dark and foggy night.

I bought a copy of Autosport, went through the ‘sits vac’ column and after a few ‘no hopers’ who promised me cars to drive, I ended up at Gemini which led to me racing their Formula Junior car. They lost their Esso sponsorship so I went to the machine shop at Phoenix. They were building an F3 car, but that fell into the ashes rather than rising from them. So, needing money, I worked for Fulham Borough Council in their rubbish tip where they said I worked too fast! Then…one evening Eoin Young from McLaren called me, said Bruce wanted to talk to me. He came on the phone and I started the following Monday. That was the first of two calls from Bruce that changed my life.

A change away from McLaren helped Ganley make his mark in Formula 3 with a Brabham

Mcklein

What was it about Bruce that inspired such loyalty and respect from everyone who worked with him at McLaren?

HG: I’m sure you’ve never heard a bad word spoken about him and you never will – apart maybe from the mechanics after their third all-nighter on the trot. He was the most charismatic guy you could ever meet, a joy to work for; he had a huge work ethic and pulled everybody along with him. The whole team would have followed him to the end of the earth. It was a brilliant time. We were all from New Zealand except Tyler Alexander, who’d come with Timmy Mayer and stayed on after Timmy was killed. There was some logic in having us Kiwis because we’d all made a huge effort to get to England on the banana boat and we weren’t going home. We didn’t have wives or girlfriends, so in the evenings we could either watch TV or stay at McLaren and make things. We simply stayed at work.

Ganley (left) alongside Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Peter Gethin during the Marlboro BRM days in 1972

DPPI

Did you tell Bruce you’d come to England to be a racing driver rather than a fabricator at McLaren?

HG: He knew I’d been racing in New Zealand and appreciated that I wanted to get back in a car. After I’d built a new back end for the Tasman car we went testing at Silverstone and he said “bring your helmet” so I had five laps in the car, the most powerful thing I’d ever driven. It was absolutely wonderful. When I decided to leave Bruce wasn’t there, so I handed my notice to Teddy Mayer, but when I went to get my final pay cheque Eoin Young said they thought I was bluffing. It was the right move because I went to Lola, a 9-to-5 job that gave me time to build my own Brabham, which I could not have done as a mechanic on the McLaren F1 team. I wasn’t happy at Lola but Peter Revson came to work on his GT40 next door and offered me a job as mechanic on his Can-Am car. That paid a lot of money, enough to come home and buy a new Brabham BT21.

In a roundabout way this led to the second of those life-changing calls from McLaren, with whom you’d stayed in touch.

“Of all the people who would not be killed in a car, it was Bruce“

HG: Yes, he’d told me to keep him informed about my racing, so I used to underline my name in the Autosport F3 race reports and mail them to him. When he came back from the Mexican Grand Prix in ’69 he asked me to get to Goodwood for an F1 test. He told me he was retiring the following year, wanted to put me in the F1 team at the end of 1970, and in the meantime he’d find the sponsorship for me to do Formula 5000. So, as far as I was concerned, I was back on track with my ambition after years with the odd drive here and there that came to nothing. Free drives aren’t always what they’re cracked up to be.

How did the loss of Bruce McLaren that summer affect the team in the middle of a racing season?

HG: Personally, it knocked me sideways. Of all the people who would not be killed in a racing car it was Bruce. Barry Newman, Bruce’s neighbour and my F5000 sponsor, called me that day and he was almost incoherent. He’d driven Bruce down to Goodwood in his Rolls-Royce and he was the first to get to the accident. Bruce died in his arms; he was simply devastated. It was terrible for the two Can-Am mechanics, Jimmy and Gary, and the team was told not to come to work the following day – but they all turned up. That tells you what a great organisation Bruce had built and how deep was the loyalty, how highly regarded he was. If Bruce had survived a lot more Kiwis would have found their way to F1 after we had all stopped. After Bruce, Denny [Hulme] Chris [Amon] and me, there wasn’t another Kiwi in F1 until Brendon Hartley came along.

The 1973 season with Williams didn’t go to plan, as his Iso Marlboro Ford lacked both pace and reliability.

Mcklein

You joined BRM in 1971 alongside Jo Siffert and Pedro Rodríguez. How did that go as a rookie with two such competitive guys alongside you?

“We’re lying on stretchers and the pilot goes for a lap of the Nürburgring“

HG: Well, in typical Louis Stanley style, he’d also signed John Miles as the third driver, so I was now number four, but John had a lot of bad luck and I was put back with Siffert and Rodríguez to do the grands prix. They were ferocious competitors, mainly against each other, but they were so nice and helpful to me because they were both hoping that I’d be quicker than the other one! I tugged my forelock to Mr Stanley but I realised Big Lou was a bit of an old rogue. He had this fantasy that he was Enzo Ferrari, playing around with drivers, setting us against each other, but he was more sympathetic than Enzo, and you had to give him full marks for introducing better medical facilities. When Mike Hailwood and I both had accidents at the Nürburgring in 1974 Big Lou came to see us at the Krankenhaus at Adenau. We were both encased in plaster and he asked if we’d like to be taken back to England. ‘Yes’, we said, ‘we would’, and off he goes saying “leave it to me, boys.” He comes back later, tells us “BA will normally only take one stretcher case but I have explained that on this occasion they will be taking two.” And they did. He then says we’ll be taken by helicopter to Cologne airport “but the Luftwaffe says it’s not possible to get a big medivac helicopter onto the lawn here at the hospital… so I told them the RAF had volunteered to do the job, and then they agreed to do it.” So, down comes this big helicopter, rotors bashing into the trees, shrubs going everywhere, and we got loaded. The pilot says “so, vood you like a lap of ze Nürburgring?” – well, we’re lying on stretchers in the back of this thing, just like in MASH, and he takes off, tips it on its side, and sets off on a lap. Then he flies us to Cologne. They’d closed the airport for us, so we flew across it and landed right next to the BA Trident where we’re taken off and loaded into the plane. Big Lou was waiting for us at Heathrow; he rode with us in the ambulance to St Thomas’s hospital where he’d arranged for the expert who’d looked after Moss and Surtees to take care of us. You could not have asked for more, he was just fantastic.

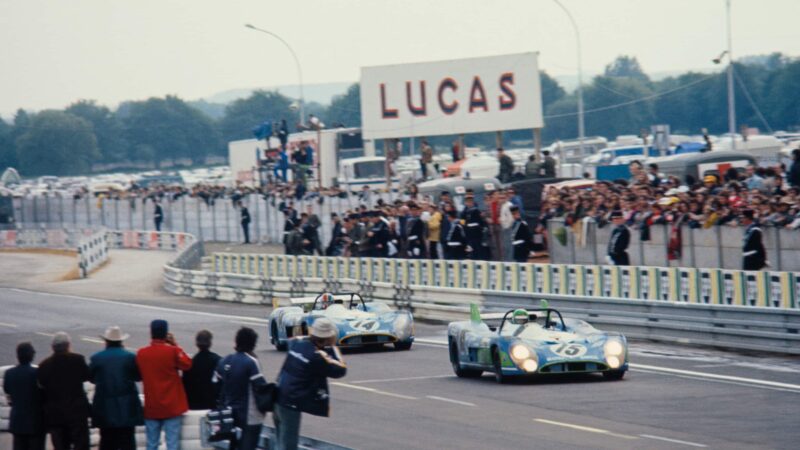

Matra succeeds at Le Mans as the MS670 of Henri Pescarolo/Graham Hill leads the sister car of Ganley/François Cevert in 1972.

DPPI

The year before, in ’73, you’d had another huge accident at the Nürburgring. You were lucky to survive that one.

HG: That was the worst one. In qualifying the brake caliper came loose on the Williams Iso Marlboro Ford at very high speed. That was really bad, life threatening, and I was very lucky not to be paralysed after hitting the barrier so hard. In ’74, in the Maki, the rear suspension failed at Hatzenbach in practice, the car turned right into the barrier and the whole front of the car fell off. That did huge damage to my legs and ankles. The surgeon back in London said there was nothing left to pin anything to, it was just all mush and he’d have to grind it together to make it heal. I wasn’t able to race again until the Nürburgring 1000Kms in 1975; all those broken bones took time to heal and I was still having trouble pressing the brakes.

You’ve worked with a lot of designers, some better than others. Who stood out for you?

HG: Robin Herd, Tony Southgate, Bernard Boyer at Matra, all very good designers. Tony did some brilliant cars for BRM, the 153, the 160 and the 180, and his BRM Can-Am car, the P167, was very good too. I’d tested the Can-Am McLaren, and the March, but the BRM was easily the best of the three. If they’d done a better job of the season BRM would have come out on top but the McLarens were strong and reliable. In ’72 I came second at Le Mans for Matra with François Cevert, after leading for 20 hours. I worked with Bernard Boyer who I thought was excellent and his MS670 sports car was a very good car. Precious few people know this… but just before the Monaco Grand Prix Matra asked me to do some testing with its F1 car at Paul Ricard. The MS120D was fantastic, a brilliant chassis, way better than the BRM. I couldn’t get out of the BRM contract; Matra looked at it and said there was no way I was going to get out of such a well-drafted agreement. That was a huge missed opportunity but hey, I’d had so many lucky breaks, I was bound to have a few bad ones.

F1 debut came with the Yardley BRM team in 1971. His best finish was a fourth place in the USA

Getty Images

You raced for so many people, so many teams, including JW Automotive with John Wyer, who had a reputation for iron discipline in the team.

HG: Yeah, I’d heard he was a bit of an ogre and he did have a death-ray stare. I had a verbal contract with Matra to race its sports cars in ’73 but, under some pressure from the French government, it decided to drop all the ‘rosbifs’ and Kiwis, which included myself, Graham Hill and Chris Amon. However, Matra recommended me to the Gulf team with John Wyer so his right-hand man John Horsmann called and got me down to Goodwood for some tyre testing. I knew Wyer had a fearsome reputation – nothing was ever left to chance, but he was very successful so I was happy to drive for him. He’d write everything down, to the thickness of a bolt… but I liked that, never felt I had to step around him. For me, the man was not an ogre, he just wanted things done the right way and later on, when I worked on the Mirage, he was very helpful. OK, there was the time, testing at Watkins Glen in ’73, when the throttle jammed open and the car went off into the barrier. I got the death-ray stare for about an hour until they discovered it wasn’t my fault and he became my friend again!

Ganley aboard the Iso Marlboro Ford at the British Grand Prix in 1973. He’d go on to take ninth, which was at least a finish

Mcklein

There was another big character, Frank Williams, for whom you raced in F1 in ’73.

HG: Well, some context, Big Lou offered me number-one driver at BRM for ’73, good money… too good to be true. Then Ronnie Peterson called me, told me Big Lou had also been negotiating with Clay Reggazoni, offered him the same deal. So I go to meet Big Lou at the Dorchester – he did most of his ‘business’ over tea at the Dorchester – he’d sit near the front door, tell you about the sexual proclivities of the people coming in and going out. He’d go for a pee, come back and tell you the factory had just found another 25bhp for the engines, complete bulls**t. Anyway, that aside, I asked him how come he’s offered Regazzoni the number one drive? He nearly fell off his chair, the chances of me finding out were zero. Anyway, long story short, I didn’t fully trust Big Lou to deliver on his promises for 1973 and by that time the best game in town was Frank Williams with money from Marlboro.

I’d known Frank for years, ever since all he had were the clothes he got up in, and Marlboro said if I could find a team they would bring the money. I thought I’d be able to take Tony Southgate with me from BRM, but Jackie Oliver had offered him a better deal, and Frank found a guy called John Clark from March, who didn’t last long. I didn’t fall out with Frank but it wasn’t the deal I’d expected; the money wasn’t forthcoming from his side. I never envisaged what Frank would later achieve but I hadn’t reckoned with Patrick Head who made all the difference because, technically, Frank really didn’t have any idea.

Alongside Derek Bell in a Mirage M6-Ford at Watkins Glen. Mirage would win Le Mans in ’75

Getty Images

Why on earth did you decide to drive for the Japanese Maki F1 team when they’d had no experience of racing at that level?

HG: Well, it was very tempting – they offered good money, a single-car entry just for me, and by then the only firm offer I had for 1974. Surprisingly, it did have potential We did a lot of testing at Silverstone and Goodwood, but I realised they were some way out of their depth. The car didn’t comply with the FIA regulations and if, for example, I wanted to adjust the rear roll bar or the rear wing I could see in the mirrors that they would move it… and then put it back where it was! Not so good. Finally, they completely changed the car, made it legal, new layout, ahead of the British Grand Prix – but they didn’t turn up until the end of practice. They simply couldn’t face turning up with the world watching them. Anyway, after some calls to the factory, I got out in the car the next day and it was 100% better, and we did a reasonable time bearing in mind we’d lost the whole of the first day. I did tell them that it would be better to come for the entire event in future. Then came the Nürburgring and the suspension fell apart, as we’ve already talked about.

You’re taking the Maki… Ganley’s relationship with the Japanese constructor didn’t last. He was lucky to survive his horrific crash in Germany

Getty Images

Looking back, is creating Tiga Race Cars with Tim Schenken the achievement of which you are most proud?

HG: Nobody remembers Howden Ganley the racing driver, but Tiga is a lasting legacy. I’m proud of so nearly winning Le Mans in ’72 but yeah, I suppose Team Tiga is a lasting memory and I’m proud of what we achieved with it. Bruce McLaren had said to me “one day you will want to build your own car” and I said ‘no, absolutely not,’ but as you go on racing you become frustrated with some of the cars that are supposed to be the best in the world but they aren’t good enough. The solution is to build your own car, which is why I built my Formula 1 car before running out of money to race it, and that led to Tiga with Schenken. We were a good team. Tim is very organised – he set up all the systems, had everything documented, while I was happiest on the shop floor making stuff.

Ganley raced the Maki only twice, in Britain and Germany. This is at Silverstone, when the team finally turned up…

Mcklein

Finally, do you follow current Formula 1 and watch the grands prix? What’s your take on how the sport is today?

“Nobody remembers me as a racing driver, Tiga is a legacy“

HG: I watch nearly every grand prix, and I always go to Silverstone, and I think it’s become a very entertaining war between the engineers now. I admire the new technologies, but not all the silly grid penalties for changing parts, and I’m not keen on the Sprint races. It’s a great show, constantly changing, and like in wartime the intense battle between the top teams brings about the incredible rate of development we see today. The costs now are extraordinary though, and have risen dramatically in recent times. I mean, when I built my F1 car I reckoned on about £60,000 for a season – but back then all you needed was a Cosworth DFV engine and a Hewland gearbox.

Of course I’d like to see another Kiwi on the grid and the most likely candidate at the moment is Liam Lawson. It’s a shame he didn’t get the drive at Alpha Tauri, but he’s getting closer and closer. There’s a really talented young guy coming up, a teenager from Christchurch called Louis Sharp. He’d never driven single-seaters in New Zealand but he won a couple of races in British Formula 4 with Carlin last year. He’s still a teenager, but he’s a contender for the title in F4 this year and currently running a close second in the title fight. He’s showing great promise.