The Arrows that should have won: Reuniting A11 and the 1989 team

Arrows was the archetypal underdog of Formula 1 in a span of time that crossed four decades. But in 1989, its striking A11 almost hit the target, as Damien Smith recounts from a special team reunion

Lee Brimble

The Arrows glides down the pitlane, in silence for the last few metres as Derek Warwick cuts the Cosworth. The belts are undone before it’s stopped and he lithely pops from the cockpit just as he used to, as if he was half his age. There’s a reason for his speed. Warwick brushes helping hands away and walks briskly straight to the garage, without a sideways glance – and disappears into the loo. Was the reunion all too much? Is he overcome with emotion for his old racing life? Not exactly. “He’s feeling queasy,” says his old boss Jackie Oliver, with a knowing look. “It happens when it’s been a while.”

Warwick emerges ashen of face but still cracking that big familiar smile. And he’s straight into debrief mode (old habits, and all that). “Lovely gearbox,” he rattles off. “The car feels brilliant, really neutral. I wasn’t pushing, obviously.” No, it didn’t look like it! “The brakes were good too, really good. It’s amazing how much pull the engine has out of the corners, even if you let the engine revs die. It responds – you forget how much. But then I thought, ‘You know what? I feel a bit sick.’”

“He’s feeling queasy… it happens when it’s been a while”

Remarkably, Warwick reckons this is his first time back in a Formula 1 car since his final season, in 1993 – 30 years ago. That’s a surprise because no one ever loved driving racing cars, or specifically being a racing driver, more than Derek Warwick. Today, he’s clearly relished becoming reacquainted with an old flame, and one of his favourites too: the Arrows A11 from 1989. To our delight there are two of them here, the other driven by seasoned historic racer Nick Padmore – all thanks to enthusiastic Belgian owner Jean-Lou Rihon, who has brought both back to life, to be reunited here at Donington Park for the first time at a proper circuit since Warwick and old mucker Eddie Cheever were going at it in the final months of the 1980s. So what do we have? No9 is A11/02, driven by Warwick through most of 1989 and once by Martin Donnelly; no10 is A11/03, primarily Cheever’s car, but also driven by Donnelly (even though he made just the one GP start for Arrows. We’ll explain later). Both look pristine.

Man in the middle: Ross Brawn and Derek Warwick are reunited with Jackie Oliver, who worked wonders on a tight budget to keep the team afloat for years

Lee Brimble

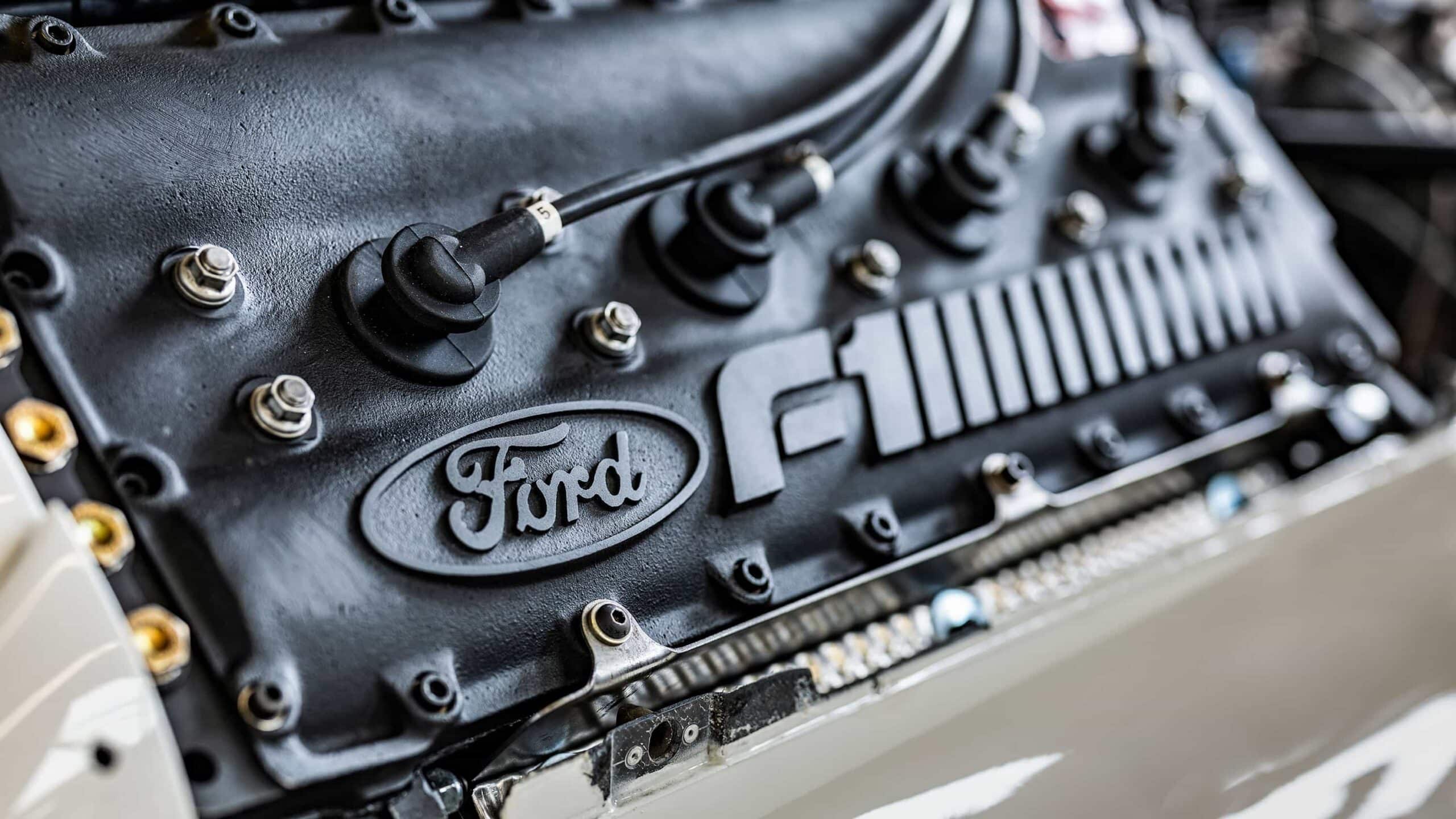

“A youngster’s dream,” is why Rihon bought the first one, no9. “My calculation was that buying a carbon-fibre chassis F1 was safer than earlier aluminium cars, with an added bet that there will soon be a race series for them.” There’s talk of that, but no solid plan as yet. “There are so many cars of that era in storage, museums and garages that there really is scope for an organiser to launch a successful series,” reckons Rihon. “And the Cosworth engine is easy and relatively cheap to maintain, with plentiful parts.”

The restoration is the work of two Arrows old boys, Kevin Drew and his mate Andy Thackham. Drew worked in the team’s sub-assembly department during the 1990s Footwork era, while Thackham is a veteran from the days of the Oliver/Tom Walkinshaw alliance. He was in the pitlane in Hungary 1997, when Damon Hill came so agonisingly close to what would have been the sole Arrows F1 win. So these cars mean something to them.

Glorious in simplicity, but also truly bespoke. Arrows spares are tough to come by

Lee Brimble

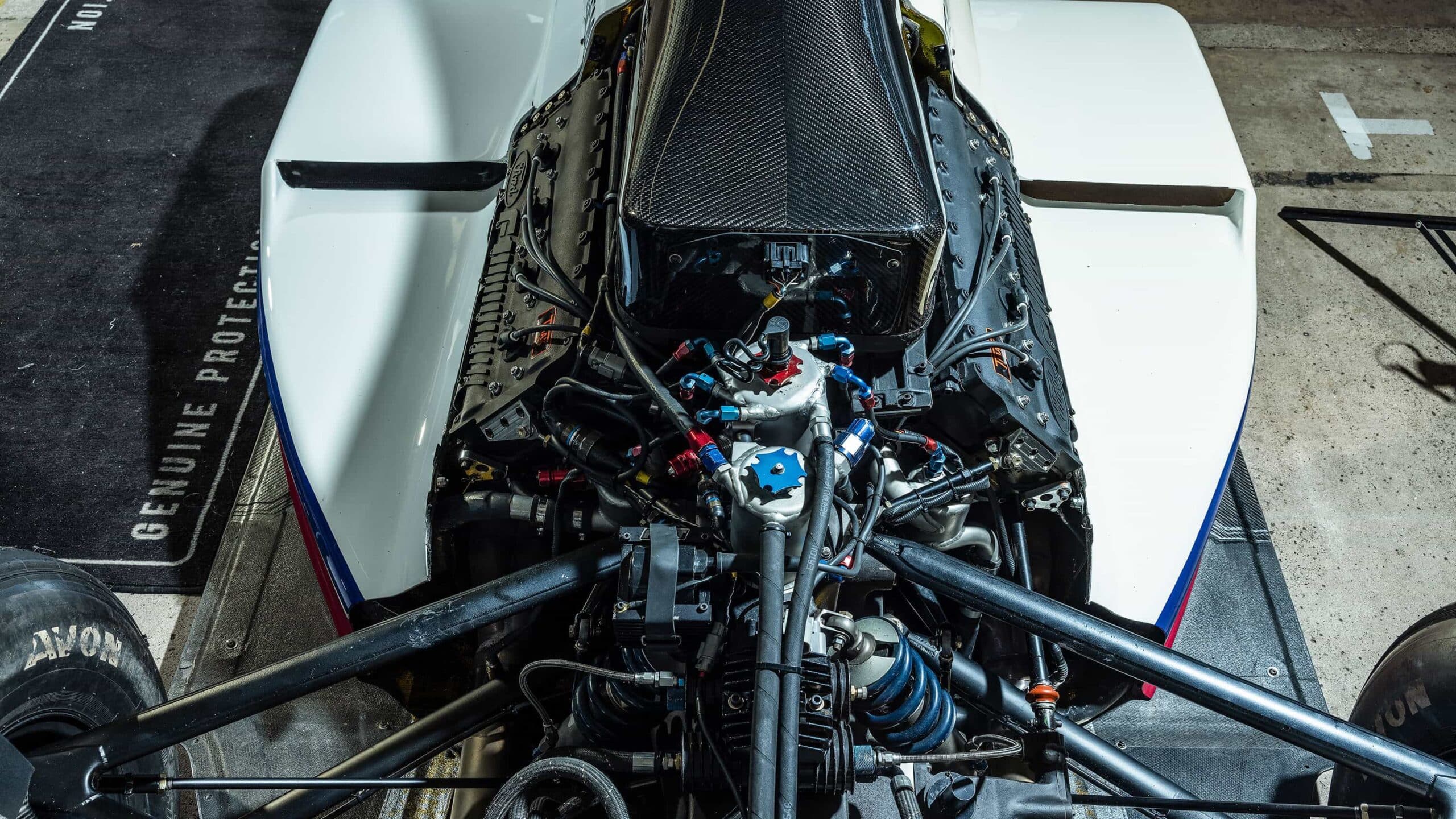

“We bought one [no9] from Belgium, damaged and in bits,” explains Drew. “The front end was complete but the rear was anything but.” The chassis spent time in New Zealand as a show car before restoration in Belgium. In 2019 it ran in a demo at Imola, but a rear wing failure led to a crash that cracked the gearbox casing. Rihon bought the car soon after. “We wanted to get the car out quickly, but we fell afoul of the gearbox casing,” says Drew. “Nobody had any. So we bought the second car [no.10] from Jackie Oliver, nicked the gearbox and the rear suspension and put it on the first car. We were up and running.”

This is the A11 Padmore drove at the one-off Goodwood SpeedWeek in 2020 (see sidebar further on). “From there, we wondered what to do with the pile of bits we had left,” says Drew. “So we decided to put the second car together again. There are no bits for these cars, everything is bespoke to Arrows. So it was a long haul on the gearbox. That was the main problem. Also the carbon-fibre was cracked and had accident damage, and various other bits and pieces were not available, so had to be remade. Then all of a sudden it all came together. The gearbox casing turned up, I assembled it and we had two cars.”

“The DFR was a breath of fresh air. To be honest, the A11 could and should have won races”

No9 was already fitted with a low-mileage Nicholson McLaren Ford Cosworth DFR, but no10’s power unit was a period dummy, so another was acquired and rebuilt. “They are both DFRs but they have different power,” says Drew. “One has a lot more torque. We don’t rev them as high as in period, but they’re reliable.” There’s another difference we can’t see. Cheever’s car has a removable panel on the seat back bulkhead to accommodate the American’s larger frame and height. In all, it’s taken four years to get to this reunion, as a weekend project. “I actually built a car in my shed at home and didn’t have the facility to get it out because I have a narrow passageway…” chuckles Drew. “So we built it, took it apart to get it out and reassembled it where we now keep it. That’s grass-roots racing.”

DFR engines were a hit

Lee Brimble

Warwick has an old set of USF&G overalls, the Megatron patches dating them to 1987-88 when Arrows ran the rebadged BMW turbos. There’s always a sense of pride when a racer can still slip into his old togs. At 68, Warwick looks trim and in fantastic shape.

He’s invited Oliver along, and the car’s designer is supposedly on his way, too. That would be one Ross Brawn. He’s kept a low profile since stepping away last year from his heavyweight role as Formula 1’s technical director, having overseen the introduction of the new ground-effect regs. So will he show? Not yet. While we wait, driver and team principal roll back the years to the ‘return to atmo’ season.

Since 1987, F1 had undergone a phased transition from turbos back to 3.5-litre normally aspirated engines. Now, in 1989, a new generation of sculpted, vacuum-packed F1 cars with airboxes sprang into life. Arrows was one of only four teams, along with dominant McLaren-Honda, Ferrari and Lotus, that had stuck with turbos to the end, enjoying what turned out to be its best season: fifth in the 1988 constructors’ standings with Brawn’s svelte A10B design.

The twins back in action. Warwick is in no9, with Nick Padmore filling Eddie Cheever’s shoes in no10. The A11 has aged well – and so has Warwick

Lee Brimble

Brawn had joined Arrows mid-1986 after a long apprenticeship at Williams and a spell at Carl Haas’s short-lived Ford-backed F1 team, where he worked with Neil Oatley and almost intersected with Adrian Newey (a big what might’ve been). At Arrows he grabbed the chance to be chief designer. The A10 and these A11s would be his only ‘solo’ F1 designs.

What did he bring to Arrows? “Attention to detail, organisation, getting the most of the people around you,” says Warwick. “He’d identify who was best for each job and he controlled it that way. I think he knew he wasn’t the best aerodynamicist or suspension guy. He was top notch, don’t get me wrong. But he got the people who would do it better and brought them together as one unit. It’s so easy not to be together.”

“Ross Brawn was my most successful designer,” states Oliver. “He was the best, which he proved when he went on do other things afterwards!”

“The trouble with the turbo era for us was we had the Megatron,” says Warwick. “Even the works BMW engine [he’d sampled at Brabham in 1986] wasn’t great. The Megatron was heavy, lumpy and had a lot of lag. It didn’t have great horsepower, the fuel consumption was poor, therefore we had to pour more fuel in than other teams. Then you came to the DFR, and it was a breath of fresh air. You ran much less fuel, had instant power, it was more neutral to drive, responded to set-up and was a very stiff car. To be honest, it could and should have won races.”

“I went underneath the ambulance, took the bumper off and broke my back”

That was always a tough call against McLaren, which transitioned seamlessly to the new era with the brilliant Honda V10-powered MP4/5. Back then, the A11 didn’t have the visual wow factor of Newey’s achingly pretty Leyton House Marches, lacked the elegance of John Barnard’s stunning Ferrari 640 and Jean-Claude Migeot and Harvey Postlethwaite’s neatly proportioned Tyrrell 018, and missed the hard-edged purpose of Patrick Head’s Renault-powered Williams FW12C – but standing alone at Donington today, it sure has aged well.

In reality, the A11 only finished seventh in the 1989 constructors’ standings, behind McLaren, Williams, Ferrari, Benetton, Tyrrell and Lotus. In his third season, Warwick clearly had the better of Cheever in qualifying and usually outraced him too, in what turned out to be the American’s final F1 season. The highlights were Derek’s fifth first time out in Rio (it could have been a podium without a sticky pitstop); an inherited fourth at Imola; Cheever’s podium third in his home town of Phoenix, one of his finest F1 drives; Warwick’s sixth on the grid in Monaco (although he stalled and caused a red flag at the first start, then lost his electrics after only three laps); and the one that really got away: Montréal. In a rain-afflicted Canadian GP, Warwick led for four laps before Ayrton Senna passed him. That Senna suffered a rare engine failure late in the day, handing Thierry Boutsen a first win for Williams, leaves Warwick convinced he would have won – had his DFR not blown.

Gearbox casings proved a real challenge, but the twin A11s are back running.

Then Warwick suffered a daft (but serious) injury. “It was a demo run up Bouley Bay hillclimb in Jersey, in a 100cc Parilla kart,” he says. “After the first run I was two-tenths quicker than everybody, so it got serious. Then when I went over the line the thing seized and spun me. There was a garage car park and they put an ambulance facing out to stop anyone going into this gap. I went under the ambulance, took the bumper off and broke my back. The fingers that come off your central spine, I broke six of them. Then I had a very interesting phone call from Mr Oliver.”

Not a flicker from Jackie. “I was an ex-driver so I sympathised,” he says, deadpan. “Never give a racing driver a steering wheel and four wheels and expect him to demonstrate only.”

That’s when rising Formula 3000 star Donnelly entered the frame, making a fraught F1 debut at Paul Ricard for the French GP. The Northern Irishman picked up damage in Mauricio Gugelmin’s famous flying shunt at the start, then switched to the spare car for the restart – which is how he ended up driving both of ‘our’ A11s. In a car set up for ‘oversteery’ Cheever, he finished a respectable 12th without a working drinks bottle.

Bulldog Warwick was back for the British GP, typically against the odds. “I was in hydrotherapy and did all sorts to get better for Silverstone,” he says. “Just to get in the car I had to have injections. Jackie was very unhappy, didn’t want to talk to me and, if I remember, threatened to fine me $25,000. Which I paid him, obviously. Cash.

“Where do you get these memories from?” sighs his old boss. “There’s a new tablet coming out soon to stop memory loss…”

Warwick and Cheever were by now a proper double-act, having shared Jaguar Group Cs at TWR in 1986. This was year four together, their third at Arrows. So… ‘frenemies’? “We were definitely that,” says Derek. “Eddie is a particular character: a lovely guy, honest, very strong principles. But he’s got a chip on his shoulder.

As it was in period. Warwick’s former ‘office’ hasn’t changed much during restoration

“We had an issue at Monaco. I was sixth quickest and went back out on soft tyres to do a quicker lap and he baulked me out of the tunnel. I went by him and he stuck his middle finger up. You don’t do that. I was already revving at a million miles an hour, so I sideswiped him and put him in the barrier [at the swimming pool]. He didn’t speak to me for ages. In Phoenix we were going to a sponsor thing for USF&G [US insurance company], got in the lift, stopped at a floor and Eddie got in. He turned his back on me. I just said, ‘Eddie, this is pathetic, we’re friends really.’ He turned around and laughed his head off. From that moment on we were back playing golf again.”

“It was a Senna/Prost situation, but in the middle of the grid,” says Oliver.

The partnership broke up as Cheever headed back to the States and IndyCar, and Warwick joined Lotus. “Jackie was struggling for budget, Lotus made me a good offer and its car was reasonably competitive,” explains Derek. “I took the Lotus because I thought it gave me a better chance, selfishly. But the Lotus in 1990 was a disaster. It tried to kill me a couple of times and almost did kill Martin Donnelly [at Jerez]. I thought it had actually when I got to Martin [after his practice crash]. It hurt me leaving Arrows because my relationship with Jackie was pure, really good. He always paid me on time, always gave me what I asked for, but he was budget-limited. That was the problem with this car. We were trying to save money on a car with which we could have won races. It was time to move on. Unfortunately I went back to an engine, in the Lamborghini V12, that was an anvil, a big bloody thing. I had a habit in my career of making the wrong move, and this was one.”

Warwick reunited with an old friend

Oliver also lost Brawn who, according to Jackie, broke his contract to join Tom Walkinshaw and his Jaguar Group C programme. “I had great legal advice,” says Oliver. “If someone doesn’t want to work for you, you can put them on gardening leave but you’ve still got to pay them. A waste of time.”

Speaking of time, Warwick slips away to don those old overalls, as the two cars are prepped for our session. Just as Derek is getting reacquainted with his old ‘office’, a tall figure appears at the back of the garage. It’s Brawn.

“We tended to start well, but then faded because we lacked the resources to develop the cars”

Is that a paternal glint in the eye as he checks out the A11s? Brawn doesn’t appear the sentimental type, but he’s enjoying blowing the dust off this old chapter. For all the success at Benetton, Ferrari and his own Brawn GP team, he has a soft spot for Arrows. These cars have aged well, I venture. “They have, they are still quite elegant, I must say,” he smiles. “Very compact and relatively simple.” And light: about 730kg with driver and a full fuel load versus more than 900kg for today’s hybrids at the start of a grand prix. That’s progress for you. So, what were the challenges of transitioning from the turbos to atmos?

“Just getting used to a different set of proportions and requirements in terms of the engine,” says Brawn. “The radiators are tiny on these things. And the turbocharged engine was messy. A four-cylinder turbo engine was not an easy thing [to package], with subframes and all the rest of it, whereas this engine was fully stressed, very compact. Yes, in some ways simpler but also more difficult to extract performance because everyone was working from a similar base.”

The budget limitation at Arrows was always a drawback. “Yeah, and that was always the frustration,” he says. “We tended to start the year well, then faded a bit because we didn’t have the resources to develop the car.”

Suddenly, the engines fire in glorious unison. Time for some laps. After a couple behind our camera car, Warwick and Padmore (who can’t believe his luck!) are let loose for some fun. They run mostly in formation, the DFRs at full song as they revel in having Donington to themselves. For Rihon, Drew, Thackley and the others gathered, these are special moments.

Afterwards, as Derek sips water and allows his stomach to settle, Ross recalls Canada 1989 and the team’s near-miss. “I was having breakfast with my wife Jean this morning and she asked, ‘What is it you’re going for today?’ I said we had the old Arrows running, the one we nearly won Montréal with and then the engine broke. She remembers being up in the suites above the pits and shouting down because they could see the rain coming. We were weighing up what we needed to do and she was shouting at me, ‘There’s rain coming, we can see it.’ That was our weather forecasting in those days! We broke the crank because you were using quite low revs in the rain, Derek.”

“Yeah, there was a vibration in the car,” says Warwick.

“It was going through this harmonic in the rev range,” says Brawn. “But I also think it was a dodgy crank, so it might have been Cosworth finding an excuse…”

“It was hand-to-mouth. But Jackie kept the Arrows team alive for a very long time”

We press him on the cars he designed himself: the A10, this one and the glorious Cosworth HB-powered Jaguar XJR-14, essentially a grand prix car in sports car threads. “The early days of Benetton I was pretty heavily involved in design too,” Brawn gently pushes back. “Rory [Byrne] was chief designer, but I’d say I pretty much shared duties in those days because I’d come from designing cars, so you don’t just stop. I was really grateful to have the weight taken off my shoulders by Rory, but I was still involved. In fact, I was still involved even in the Ferrari days, but to lesser degrees. I would stay in touch with what was going on and sometimes make hopeful suggestions. There are details on the Ferraris I can pick out that I know I was instrumental in encouraging or suggesting. But these are the cars I can genuinely say I designed. The last one I designed was the XJR-14.”

Warwick leads a very lucky Nick Padmore around Donington. During his three seasons with Arrows, Warwick finished fourth four times, but never made the podium with either the A10 or A11. Cheever was third at Monza in 1988 and also on home turf in Phoenix in 1989, their final year together

Lee Brimble

Like Warwick, Brawn didn’t enjoy letting Oliver down when he left for TWR. “It was hand-to-mouth,” he says of life at Arrows. “Jackie was very passionate, but never quite had the resources. Still, he kept this team alive for a very long time.”

In hindsight, the diversion to sports cars with TWR worked out perfectly. By the British GP of 1991, as the XJR-14 was cutting a swathe through the World Sportscar Championship in the hands of, among others, a rejuvenated post-Lotus Warwick, Walkinshaw had cut a deal with Flavio Briatore to begin a new alliance at Benetton. Brawn was back in F1, quickly forged a partnership with Byrne – and when Michael Schumacher was scooped out of Eddie Jordan’s grasp later that summer, a new superpower gathered steam. You could say leaving Arrows made sense.

“Tom had F1 aspirations and a plan laid out,” says Brawn. “It didn’t quite happen in the way we expected, because he was hoping to take Jaguar into F1. That was the plan, but it didn’t work out. But overall it did work out!”

As for Oliver, there’s a tinge of regret that his stars didn’t quite align. “The departure of Derek to Lotus and Ross to the Jaguar programme was the biggest loss for us,” he says. “When they went I got all the money I’d dreamed of through Footwork.”

“The really big money comes with success. And success was always just out of reach”

Wataru Ohashi’s mail-order corporation came in for 1990, acquiring a stake in the team to turn the A11Bs red and white. A year later, factory Porsche V12 power promised a game-changer, only for the engine to prove a disaster – a strange blemish on Porsche’s competition record. Typical Arrows luck. “Although the Porsche engine was a disappointment, Derek and Ross – Ross in particular – would have sorted it out,” asserts Oliver.

“This guy worked his ass off to get us the money to go motor racing,” says an ebullient Warwick. “It wasn’t wasted, squandered or put behind closed doors. It was all put into the race car – but it wasn’t quite enough. We had to cut a few corners, but we did so together.”

“I’m a good salesman, it was one of my strengths, I could raise money,” says Oliver. “But the really big money comes with success. And success was always just out of reach. The difficulty with F1, and it’s the same now, is the major successful teams have control, and they use every method to prevent a team from the back of the grid displacing them. As Eddie Jordan said when he got involved, welcome to the Piranha Club.”

The Arrows reunion crew, from left: Jackie Oliver, Ross Brawn, Paul Willow, Jean-Lou Rihon, Derek Warwick, Chris Davies, Kevin Drew, Andy Thackham and Nick Padmore

Lee Brimble

After the Footwork era, Oliver struck a new alliance with his old nemesis Walkinshaw, before selling his share in Arrows to Morgan Grenfell. Under Walkinshaw, the team went under during 2002, taking the once-great TWR empire with it.

“There are no private F1 team owners any more,” says Oliver. “The privateers died off when Frank Williams died. Wealth and power rule the day.

“But I survived. I was an F1 team owner for 30 years and I’m still standing. As Bernie said to me, ‘You never won a race, but you lived long enough to prove a point.’”

Our thanks to Jean-Lou Rihon and Donington Park, and all who contributed to the Arrows A11 revival