Fire Inside: Interview with Simon Pagenaud

Destined to never race in Formula 1, Simon Pagenaud set his sights Stateside. Chris Medland talks to the Frenchman about IndyCar success and how he still loves “the feeling”

Jonathan Ferrey/Getty Images

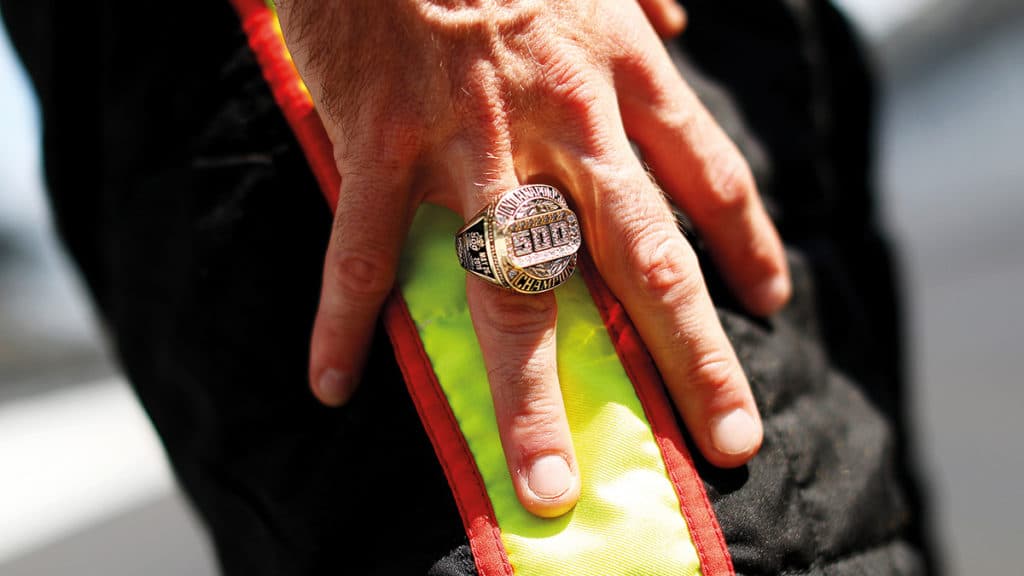

As Simon Pagenaud perches on a picnic bench watching the likes of Michael Jordan and David Beckham stroll past him in the Miami Grand Prix paddock, he’s a contented man. An IndyCar champion and Indy 500 winner, it’s not the fame and fortune of the A-list celebrities in America that he might have been dreaming of, but the chance to be a regular in the Formula 1 circus.

The Frenchman hit headlines in the F1 community during the first Covid-enforced lockdown in 2020, crashing into Lando Norris during an online race. But he could well have been on the grid himself long before Norris – who he calls “an amazing talent” – was even karting had he been taking his real-life racing more seriously at an early age.

“For every kid growing up in Europe, the dream is Formula 1,” Pagenaud admits. “And it starts in karts. I did go-karting but at a very low level with zero pretension to become a professional driver. We used the same chassis for seven years, and I think we had one engine for five years. It was really low budget.

“But it taught me to work on my go-kart myself, and it taught me to work hard with tough equipment. So I didn’t get it all at once. Then my chance was really when I won the [FFSA] driving selection in Le Mans, and that money basically helped me start in racing.

“Originally I was just going there to get my licence to drive on track before I was 16 years old. I ended up winning and my dad was out of sorts, not understanding what was happening next. So we started racing!

“I finished second the first year of single-seaters with zero experience of really high-level racing. Renault was a huge help to continue forwards, but I think it cost me at the same time. It helped me in a way but it cost me because I wasn’t like a Max Verstappen at 18 – I wasn’t ready.

“I would say having friends at 18 kind of impacted my discipline a bit. It meant it took me a little longer to get there and learn the job because I also had nobody really teaching me the job of a racing car driver. So fitness came later, mental training came a bit later, and discipline too.

“I had the chance to have a contract with Renault F1. I had a chance, a far chance to think about Formula 1. And then I realised when I was about to try and go to GP2 that I didn’t have the budget, I didn’t have the connections and I hadn’t made a big impact.”

Pagenaud had won races in every series – including against the likes of Lewis Hamilton – until he reached Formula Renault 3.5 in 2005. Then he hit a crossroads. With Polish driver Robert Kubica comfortably taking the title and with no fewer than four other Frenchmen ahead of him as he finished 16th overall, Pagenaud took a risk to save his fledgling racing career.

Simon Pagenaud was astounded by Lewis Hamilton’s talent

Getty Images

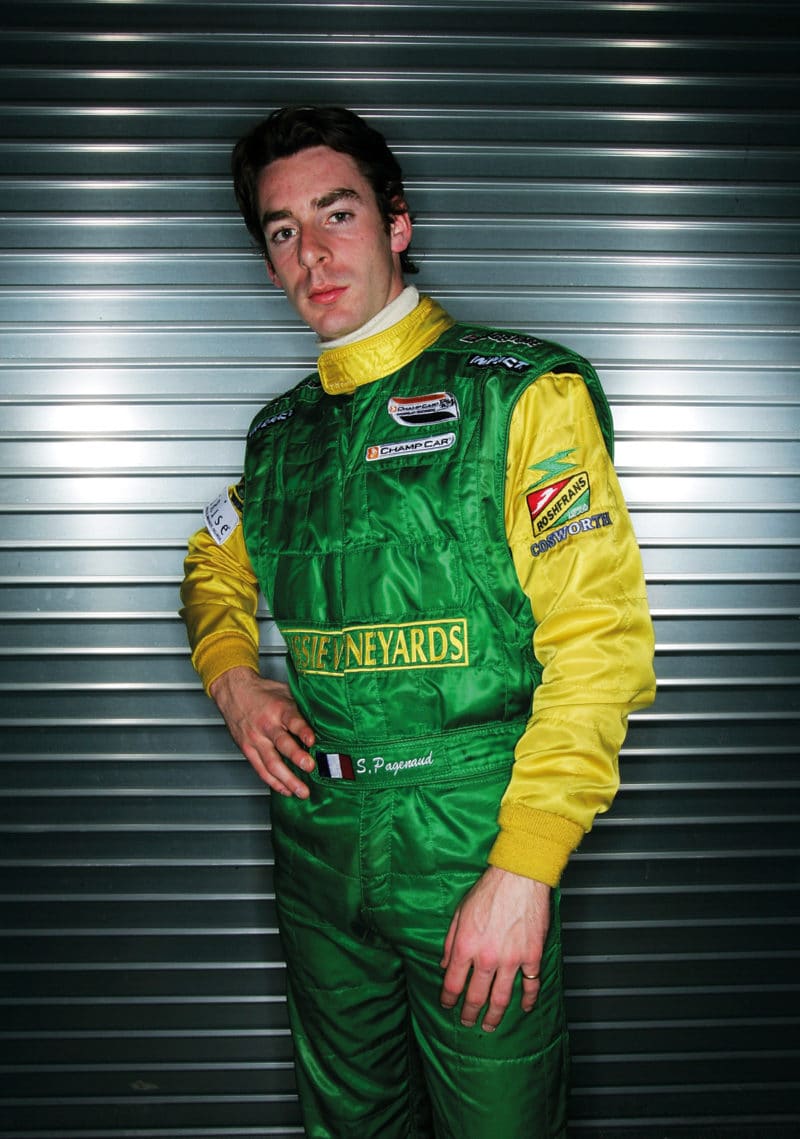

In Formula Renault days; racing a Panoz in Champ Car, 2007

Jonathan Ferrey/Getty Images

With Frédéric Le Floc’h

DPPI

“I felt like I had to turn it around, and I felt like now I finally knew exactly what I had to do to be at the top level, but I hadn’t shown it enough. So then I decided, ‘OK, either Japan or the US,’ and the US had a great programme with the Atlantic Series.”

At a time when there was no social media or websites to help him get in touch with teams in the United States, despite all but turning his back on his F1 dream, Pagenaud was able to lean on a future grand prix driver to open doors: Sébastien Bourdais.

“I tried to get contacts, but then really Sébastien would help me the most because he was already established in the US. He was winning everything, so a phone call from him was going to do everything and I’m sure he had phone calls from a lot of people. But Sébastien and I had a solid French friendship, I’d say a relationship that might have been different than the others.

Driving for Oreca-Matmut, left, in qualifying at Le Mans 2008

Mike Hewitt/Getty Images

“So Sébastien made some phone calls and we went to the US with my dad. We went to the Mexico City race and met a lot of people there and that’s where everything started basically. What I learned in the US is that’s very much the American culture to network. I found that being there, showing my face, sending emails, introducing myself was going to make the difference. And it did. I just kept harassing people and I kept trying on the phone and I think it helped me because those connections helped me for the future.”

Pagenaud’s diversion away from the European ladder took him to a similar point in the American system, joining the Walker Racing-backed Team Australia set-up in Champ Car Atlantic.

In a championship that featured future IndyCar race winners Graham Rahal and James Hinchcliffe, it turned out to be his one shot to make it into the top level – at the time – Champ Car series, and he duly took the title.

“I was finally at the level I was supposed to be at, and basically it was a reset button because nobody knew me in the US. But I came in and I won and I made that impact – and it shaped my career for the rest of it.”

Yellow and green of Team Australia from the 2007 Champ Car series.

Jonathan Ferrey/Getty Images

Stepping up to Champ Car alongside Will Power in the same team, it was a good rookie season for Pagenaud, where he went up against a driver with “tremendous speed, different than most drivers… Just magic speed out of nowhere.

“Will would be doing the same lap time as you would, but then suddenly when it was most important, there would be magic speed coming from him more than the car and he would transport the car to a lap time it wasn’t supposed to do.

“I would say having friends at 18 impacted my discipline a bit”

“I definitely learned from that a lot because as a driver you always look to make the car feel what you need for you to go that fast. But Will could go in a different dimension. It was really impressive in the same way as Lewis can do it or has done it in the past.

“It was a great year with a smallish team, we had some good racing. I finished eighth in the championship as a rookie, which was strong and really good expectation for the future. But all of a sudden in the winter the series stopped.”

After finally feeling like he was on the verge of making it into a top-level open-wheel series, Pagenaud was back to a position where he was having to try and make contacts and put his name about.

Schmidt-Hamilton, IndyCar, 2012

Robert Laberge/Getty Images

A win in Meyer Shank Racing’s Acura at the Daytona 24 Hours

Brian Cleary/Getty Images

Pole for Peugeot at Le Mans 2010, from left, Pedro Lamy, Pagenaud and Sébastien Bourdais

JEAN FRANCOIS MONIER/AFP via Getty Images

“The funny thing is there was a bit of a war between Champ Car and IndyCar, so the team owners from IndyCar wouldn’t talk to me or I wasn’t known enough. And again I had to do the work. So that year, basically at the end of 2007, I started making connections in the IRL [Indy Racing League] and in the meantime went sports car racing.

“I was managed by Derek Walker at the time and he said, ‘Listen, just be the best driver in sports car racing. And then when you’re done with that, you can try to be the best in IndyCar racing. But right now your chances are in sports cars. I understand your dream is to go to IndyCar but you’ve got to make the best of it to have a chance.’

“It was war for Champ Car and IndyCar, teams wouldn’t talk to me”

“So I really did that. But I did lie to Gil de Ferran when he hired me and he asked, ‘Do you want to be a sports car driver forever?’ I said, ‘Absolutely. I want the deal. Yes!’ But I was lying. I just wanted to be the best sports car driver, win Le Mans and show myself and have a chance in IndyCar later on. It worked!”

Joining De Ferran Motorsports in the American Le Mans Series meant a relationship with Honda – under its US racing name Acura – began in ’09, and Pagenaud’s work convinced the engine supplier that he could be a good fit for IndyCar, opening doors to conversations that had previously appeared off-limits.

Overjoyed at Baltimore with his second IndyCar victory of 2013

Rob Carr/Getty Images

“Back then the regulation [in sports cars] was open. We could do whatever we wanted. And Gil nurtured me as his protégé and he taught me everything about the technical side of motor racing. So I brought a lot of feedback to Honda on the engine development and they liked that.

“When it became the new era of the DW12 in IndyCar, Honda thought I could be the development driver. I made the connection between Schmidt and them and they helped Schmidt with the engine lease basically to get me a full-time seat. So that was a lot of work in the background, a lot of my connections that ended up working long-term.”

While racing for Schmidt was the big opportunity in getting a full-time IndyCar ride, there was to be another step. Two wins in each of 2013 and 2014 resulted in top-five championship finishes, and soon Roger Penske came calling.

“When I first signed my contract with Schmidt, there was a lot of emotion. I remember sitting in my apartment in Indy and thinking, ‘Wow, OK, well, I’m at the top of the pyramid now. I’ve got to make it count.’ And that was certainly the same the first time I talked to Roger Penske. It’s like, Rick Mears has driven for him, all these amazing drivers, and you’re thinking about the history and being part of the history. ‘Wow, OK, I think I’ve done something pretty cool, but now let’s make it legit and let’s win races.’ So that was a very special moment at the end of 2014.”

At 32, Pagenaud delivered on that aim, adding his first IndyCar championship in a year when he felt the car and engine package suited his driving style perfectly. He nearly defended the title a year later, finishing runner-up, and a dream Indy 500 win in 2019 led to another championship near-miss.

But after seven years and great success with Penske, the Frenchman took on a different challenge by joining Meyer Shank Racing this season.

Basking in the moment at the 2019 Indy 500 with Team Penske – Pagenaud was the first Frenchman to win the race since Gaston Chevrolet in 1920

Chris Graythen/Getty Images

“I have qualities I wanted to use that Penske didn’t need because it’s such an established team. It’s like a Mercedes, it’s like a Ferrari – the driver comes in and they bring feedback, but they want the drivers to drive because everything else is set up. With how I am, I love personal performance analysis and the technical aspect of racing. I also wanted to take the next step of my career and help a team progress and go to the top, to do something that for the future I also might think about as a second job later on.

“It’s something that I’m really interested in, not only just driving, but the management side, the performance analysis or performance consultant – that is something I’m really into.”

Given his evolution, Pagenaud is well-placed to judge a variety of drivers and their skills, having raced some of the biggest names in junior categories, US open wheelers and at Le Mans. While Giedo van der Garde gets an honorary mention, aside from Power there’s one driver who he’s proud to have raced against even earlier in his career.

“I felt like Lewis’s car was inferior, but I couldn’t shake him off”

“Lewis Hamilton, number one. There was a race with him in Assen, in a Renault 2000, it was 2003 and we battled. I honestly felt like I had the best car that day. He was with Manor. I felt like his car was inferior, but I couldn’t shake him off and he damaged his front wing on my rear tyre, and kept racing like nothing happened.

“He just had something different. It seemed like he was floating over the racetrack and you felt like when the car wasn’t there, he was still able to put it on the front row, second row. That was special.

“But also Lewis always had this reputation right away. We were growing up in go-karts and obviously McLaren was behind him. He had this aura around him. But certainly in terms of driving, he’s one of the drivers that surprised me the most.”

In IndyCar, Pagenaud departed Penske in 2021 and now wants to take his new team, Meyer Shank Racing, to the top

James Gilbert/Getty Images

Perhaps Hamilton will have been surprised that the driver who held him off that day never quite got to F1, but Pagenaud certainly worked hard to open other doors that led to one of the more eclectic and successful career stories in modern motor sport. And it has plenty of chapters still to be written.

“I want to bring Meyer Shank Racing to the top with me as the driver. And I don’t know how long that’s going to be. I hope it’s going to be for another 10 years, quite frankly. I have so much fire in me to drive. I just love the feeling.

“We’ll see after that. Certainly, if there’s room at Meyer Shank Racing or somewhere else, or if there is backing behind it to build my own team, why not?”