Smoke and Heat: Lotus in the JPS days

Mike Doodson was Lotus's PR man during the tumultuous early days of JPS sponsorship. Here he relives the drama

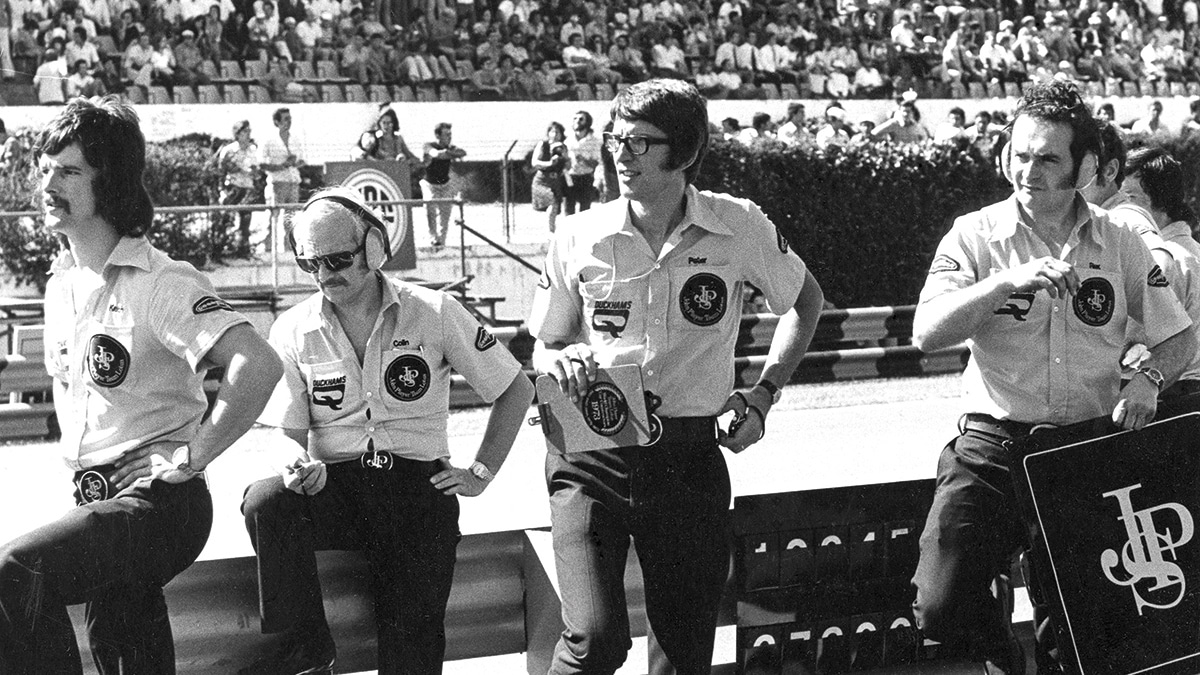

Fully branded: JPS logos everywhere in Argentina 1973. Colin Chapman (sitting), Peter Warr and Eddie Dennis look the part on the pitwall.

Grand Prix Photo

Although I had no more than a small role as the team’s press officer during the black-and-gold glory days of the Lotus 72, I had a ringside seat at someof the not always proper events that went on behind the scenes at John Player Team Lotus, as recounted below. Lawyers please note: only a few of the alleged wrong-doers are still with us.

I was recruited to the job early in 1972 by Peter Warr, who had managed Team Lotus very capably for Colin Chapman since 1969, and with whom I had become friends during my two seasons as F1 correspondent for the weekly newspaper Motoring News. Warr did not have to press me very hard: at the time my salary at MN was a slum-level £1000pa (augmented by £200 from the position I briefly occupied as deputy ed of its monthly sister publication, Motor Sport) – and Warr was offering £3000.

Lotus’s racing activity (F1, F2, F3 and sports cars) had been sponsored by Player’s Gold Leaf brand since 1968, initially to the tune of £85,000. For 1972 the cars would wear the funereal colours of Imperial Tobacco’s new John Player Special brand. No doubt a useful increase in budget reflected the attempted eradication of Lotus’s hard-earned identity.

To liaise with Players and to churn out promotional material Warr had used the services of two pals, Noel Stanbury and Barry Foley. Both men had been keen competitors in the flourishing Clubman’s racing category, for front-engined Lotus 7-type sports cars.

Foley, a graphic artist, had designed the JPS logo and livery for the F1 cars. He was much better known, though, for drawing the popular Catchpole strip cartoon which entertained the readers of Autosport every week for 24 years.

Stanbury-Foley set up business in premises in Stratford, east London. I don’t remember being given a precise outline of my duties, perhaps because I was the very first of a new breed of press agent, uniform and all.

Although I was to accompany the team to virtually all its races, and to assist the press, the latter function did not always sit well either with Warr or with the understandably cagey Chapman. Though willing to reflect for the media on last week’s race, their ferocious competitiveness rendered them frustratingly unforthcoming about the stuff that the press really wanted to know, namely whatever upgrades they had in mind for next week’s confrontation with Tyrrell and Ferrari.

Nonetheless, Messrs S&F were determined to exploit the potential of their client’s sponsorship. An important leg in the ‘liaison’ they had envisaged was for the Lotus name to be dropped altogether in favour of ‘John Player Special’. At one planning meeting I was instructed that my mission was to patrol the press room, overlooking journalists as they toiled at their typewriter keyboards and to demand that the word ‘Lotus’ be expunged in favour of ‘John Player Special’.

I protested in vain that most of the pressmen in F1 were friends whom I respected, and that this amounted to unethical editorial intrusion. Although the matter ground on for a while, it was eventually settled by Chapman himself, who stolidly continued to refer to his cars as Lotuses when talking to the press. Sometimes he would hesitate and use the ‘correct’ nomenclature, but never convincingly.

“The dump was closed, so we had to use our ingenuity to liberate our fuel”

‘Affection’ is not a word that you’ll often see attached to Chapman. In my first season of reporting F1 I was close to Jochen Rindt, whose respect for his team boss sank noticeably lower as the 1970 season wore on, even after he’d won four GPs in a row. I was in the Lotus pit at Monza when Jochen was killed on the day before the Italian GP, and I was aware of the doubts that hung (and still hang) over Chapman’s insistence on running the Lotus 72 without wings.

Now there was the vexed question of my personal transport. The sponsorship deal required Players to pay my salary and expenses, and Lotus to supply a Lotus Elan. Warr stalled me for weeks. Then he informed me that an Elan Plus 2 had been selected for me, but that it would be delayed, “because we have to get the chairman’s scratches polished out of the roof”. Chapman had been giving it a ‘test’ when he flipped it into a Norfolk ditch.

Once rebuilt, it was a lovely looking car, but hardly dependable. Its weak point was the rubber driveshaft doughnuts. One failed me en route to the British GP. I managed to get towed to a Lotus dealership in central London, but despite the black and gold livery the service manager refused to book me in. As he pointed out, the workshop was packed with immobile Elans, all in need of unobtainable replacement doughnuts. Warr wangled a pair for me, but I had to collect them myself. In Norfolk. By train.

I had other adventures with the Elan. The most terrifying was when Emerson Fittipaldi, desperate to get home to Switzerland from Silverstone, commandeered my car for the dash to Heathrow. Halfway there, at top speed on the M1, a huge bang signalled that a rear Dunlop had delaminated. “Don’t worry,” Emerson shouted through the din, foot still hard down, “one did the same on my Elan. It’ll be OK.”

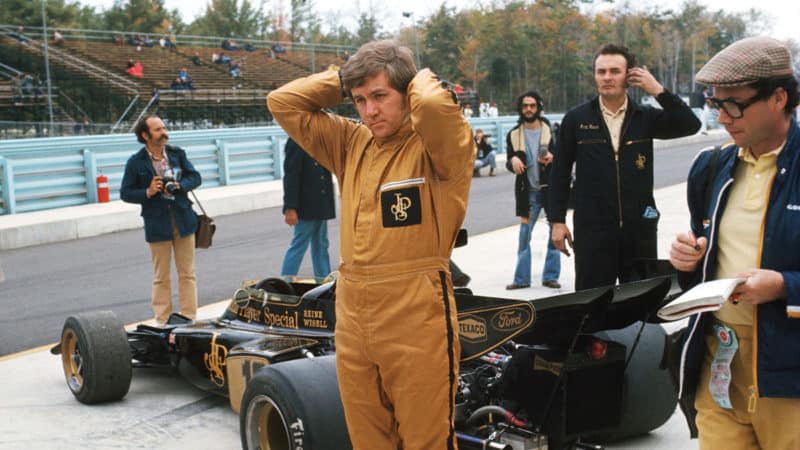

No Lotus branding on Dave Walker’s overalls at the ’72 US GP as journalist Jabby Crombac takes notes

Grand Prix Photo

Then there was the occasion in 1973 when I was ferrying our two drivers to the opening of a Texaco service station in London and we were stopped by a cop for making an unauthorised right turn. Fortunately, he must have been an F1 fan. You should have seen his face when he peered into the cockpit and recognised world champion Fittipaldi and Ronnie Peterson. We got away with that one.

Lotus was notorious for bending rules, and the most egregious instance that involved me was at the French GP in 1972, held at the scenic road circuit of Clermont-Ferrand. It had been decided we would hold a dinner on the Friday for the British media in an attempt to drum up a bit of enthusiasm for the team’s second driver, the Australian Dave Walker, whose skills in F3 had not transferred at all comfortably to F1.

I reserved a small dining room at a Michelin-starred restaurant in central Clermont and put out invitations. To add gravitas to the occasion, also present would be Geoffrey Kent, the main man at John Player and an ex-RAF officer. This would be a major test of my press officer-ish skills. I yearned for nothing to go wrong, but…

Our fuel sponsor, Texaco, made a racing brew which had been despatched as usual from America. For the Clermont-Ferrand race it had been agreed that the fuel would be delivered to a fuel dump on an out-of-town industrial estate. However, soon after our cars had ceased running for the day, I received instructions from Warr, who knew I spoke French, to go with two mechanics to pick up the fuel. As the dump had been closed for the weekend we would have to use our ingenuity to liberate our gasoline.

When I protested to Warr that I was due to host the Walker dinner party, he insisted that my first priority was to the team, and that anyway I’d be back in a couple of hours. Needless to say, I wasn’t. Gaining access to the dump had required wire cutters and a lot of scuffling in the dirt, with the result that I arrived two hours late at my own party ina state of dishevelment, which went down poorly with the self-regarding Mr Kent.

Doodson today

And what of Dave Walker? By coincidence, I bumped into him at least 10 years ago while visiting another racing driver friend on Australia’s Gold Coast. We found him on the marina where he had a boat hire business, recognising one another immediately despite him showing signs of a bad road car accident.

Stanbury-Foley did not survive a scandal late in 1973 when a Player’s executive – with whom they were involved in a Portuguese holiday property scheme – was summarily dismissed, for reasons that the company never revealed. Noel Stanbury later became a sponsor-finder for Ken Tyrrell

After 18 months of intermittent service, the black and gold Elan Plus 2 broke down on the M40, suddenly and mysteriously, in mid-winter, obliging me to abandon it.

Early in 1974 I successfully applied for the post of sports editor at Motor magazine, where I resumed my globe-trotting career for almost 10 years before going freelance. For several of those years my life was shared by a woman I had met when she, too, was employed at the office in Stratford. Among the many things for which I have to thank her was her insistence that I stopped smoking.

This month it will be 50 years since I stubbed out my last cigarette.