Vern Schuppan: The Motor Sport Interview

From co-driving a 956 to Le Mans victory and helping Adelaide get its own F1 GP, to the perils of supercar projects. Aussie adventurer Vern Schuppan expounds on precious moments and big characters

Vern Schuppan arrived in Britain at the end of the 1960s with enough money to buy and race a Formula Ford

Getty Images

Motor racing’s path from Down Under to Up Top is well trod: Jack Brabham, Denny Hulme, Alan Jones. It’s too far to travel to fail. Though South Australian Vern Schuppan’s pilgrimage did not lead to such vaunted Formula 1 success, it resulted in most things else, including victory at Le Mans, an Indianapolis Rookie of the Year and two Macau Grand Prix wins.

He won state championships in karts and national titles either side of the Equator – UK, Australia, Japan – in formulae Atlantic and 5000 and a Group C sports-prototype. He set fastest lap on his Bathurst debut. He drove for racing gods Dan Gurney, Graham Hill and John Surtees; for team chiefs as chalk and cheese as John Wyer and Sid Taylor; and for himself – finishing third at Indy in a five-year-old McLaren crewed by “a lawyer, a policeman, a doctor”.

Having rocked up in England in 1969 with £2000 in his pocket – to buy, prep and run a Formula Ford – and supportive new wife Jennifer on his arm, this former “larrikin” of back-home infamy aboard sideways Simca Aronde and Riley Pathfinder was soon at the wheel of a Formula 1 car.

If it had four wheels and an engine, Schuppan “stood on it from the get-go”. If an offer of a drive was “half-decent”, he accepted it. He competed in: Alexis, Macon, Merlyn and Palliser; BRM, Ensign, Hill and Surtees; Chevron, Elfin, Lola and Trojan; Eagle, Lightning and Wildcat; Fords Capri, Falcon and Granada; Mirage and works and privateer Porsches; and – for his last and victorious race before retiring in 2018 – the Talbot-Lago that had sparked his imagination 63 years before.

Today he lives with Jennifer overlooking the Adelaide grand prix circuit that he helped make a reality. Covid restrictions have at last given him a chance to delve into cardboard boxes full of memorabilia, some of which he displays now in a pair of glass cabinets.

He views it all with a wry grin and twinkling eye while nursing an evening drink: G&T (taken with a cucumber slice) or whisky mac. Spend as long as he has in and around this sport and one is bound to experience its dark side: High Court torture, the desolation of bankruptcy and the agony of a spoiled friendship.

But good guys able to laugh at themselves tend to bounce back. That friendship has since been restored; and so, too, has the ex-Steve McQueen Ferrari road car – from Spider to original Berlinetta – for which Vern received more than £6m at auction in 2014.

Motor Sport: Did your family have a motor sport background?

Vern Schuppan: “No. Dad [Norm] started out as a garage mechanic, moving to a small farming town called Booleroo Centre where he looked after the town’s lighting plant. I was four weeks old when we moved to Whyalla. He learned to fly there and won a couple of cups – I have them here – in a Tiger Moth. Then he bought a Moth Minor, a single-wing, twin-cockpit thing. He sat in the back flying it – and filming on an 8mm movie camera – with me on Mum’s lap in the front. I still have black-and-white footage of us over the blast furnaces and shipyards.”

Did he encourage your racing?

VS: “We had a beach shack 27 miles of rough road away from Whyalla and Dad would let me sit on his knees and steer the car. He would go fast enough so that I could have opposite-lock on. I was probably only five or six years old at the time.

“The local Standard agent, he also took me, Mum and my sister to the 1955 Australian Grand Prix in a slopey-back Vanguard. My first race, I was 12. Reg Hunt had a Maserati 250F and everybody expected him to win – but Jack Brabham did in a Bobtail Cooper. The car I remembered most, however, was Doug Whiteford’s beautiful, French blue Talbot-Lago. It finished third.”

So your father did encourage you?

VS: “Well… My parents sent me to Adelaide’s Lutheran Concordia College and every weekend I rode my bike to Elfin’s, where Garrie Cooper was designing and building Formula Juniors. He let me wander around. And that’s what really started it.

“Dad was mad at me: ‘If you go to Britain, don’t come back!’“

“I worked for Dad from the end of that year and began getting bits together to build a Junior. There were always a number of rolled Beetles at our panel-beating business, but when I grabbed a VW gearbox, Dad said, ‘No way are you going car racing! If you give this up I will help you buy a go-kart.’ It was probably the worst thing he could have done. He started racing go-karts, my sister started racing go-karts and we became a racing family.”

How bold was your decision to travel to the UK given that you had no experience of car racing?

VS: “Dad was more than mad at me: ‘If you go, don’t come back!’ In my mind, however, I was convinced I would make it. I had won countless go-kart races.

“Apart from karting, I was driving all the time: I had a car for two years before I had a licence. Local VW dealer Alan Melville, who had raced motorbikes, asked if I would like to drive with him and an observer to Perth and back in one of the new 1300 Beetles. Leave Friday, back Sunday: 3000 miles, much of it on unmade roads of the Nullarbor. We drove flat out. The VW dealer in Perth fitted new shock-absorbers and we drove flat out all the way back. A 78mph average.”

Another F1 chance came in ’74 with Ensign, but in Germany his N174 failed. His seven races with the team weren’t happy ones

mcklein

Final F1 outing in a Surtees TS19 at Zandvoort in 1977

mcklein

Vern, centre, with wife Jennifer and 1985 Indy 500 winner Danny Sullivan at 2022’s British GP

Grand Prix Photo

Did Jennifer take much persuading to make the UK trip?

VS: “Not really. I said to her, ‘If I don’t make it as a professional driver within two years we’ll have had an amazing adventure and we can do whatever you want to do.’

“I had been to the UK before. I was all set to go on a working holiday when a mate asked if I’d delay because he wanted to come, too. My plan was to go to the UK via Japan and the Trans-Siberian railway, get a job with a team and get into car racing that way. I delayed for two years, by which time Jennifer and I were serious. So when I went in 1965 it was for only four months. I was itching to get back – and gave myself two years the next time.”

You were in F1 after two full seasons. How?

VS: “My first lucky break came on my third race weekend. I entered my car, an Alexis, in three Formula Ford races in different parts of Britain because more often than not fields were full and you wouldn’t be accepted. Lydden Hill’s organisers told me to come down and that I’d get a race if there were no-shows. Eventually they started me from the back of a Formule Libre race: I got fastest lap and finished in third.

“That led to a factory drive with Tony Macon, who built Formula Fords mainly for the American market. As I recall, I was on pole six times but just couldn’t get it off the line. The gearlever went straight into a spherical ball joint and when you pulled from first into second it would swing around and not go into gear.

“Upon my return from competing in the winter Temporada in Brazil in a British Airways pilot’s Merlyn – an eight-race series from Fortaleza in the north to Curitiba in the south; that was a great experience – one of my first races was at Crystal Palace in a new Formula Ford Alexis loaned to me by the factory. There Hugh Dibley – along with Neil Johnson, who ran BRM’s commercial division – asked if I would like to drive one of his cars: a Palliser, with engines by BRM. I had a pretty good year and they wanted me to do another, suggesting that I could win the championship. But because my plan was to move up each year, I persuaded them to let me do Formula Atlantic, a more powerful and sophisticated car than Formula 3. I won the Yellow Pages Championship in 1971.”

That Atlantic Palliser also used a BRM engine. Was that the next link in your motor-racing career chain?

VS: “I used to drive to the BRM factory in Bourne and hang out there. Eventually Neil introduced me to the owners: ‘Big Lou’ Stanley and his wife Jean, who had white hair piled up in a big beehive. They made a fantastic promise: ‘If you win the Formula Atlantic championship, we will give you a Formula 1 test drive.’ I got a contract for 1972 – races, testing, reserve driver – and the first time I sat in an F1 car was on the Friday before the Oulton Park Gold Cup. The BRM P153 was fantastic to drive. Like a big Atlantic. I finished fifth ahead of some big names.”

A winner’s trophy at the Oran Park 100, the opener of the 1976 Rothmans International series.

Fairfax Media via Getty Images

BRM had by then gained a reputation for being madcap. What was your experience?

VS: “They sent me to Nivelles for the Belgian Grand Prix. When Peter Gethin crashed during practice they gave my car to Helmut Marko. My second outing with BRM wasn’t until the John Player Victory Race at Brands Hatch in October: I finished fourth after qualifying 15th because I hadn’t been able to get out before it rained.

“After that I got a call from team manager Tim Parnell inviting me to test at Silverstone. Big Lou’s next call invited me to tea and scones at the Dorchester. It was going to be a two-car F1 team in 1973 – me and Clay Regazzoni – and he wanted me to sign there and then. Crikey! You’re supposed to take those things home and read them, aren’t you? Lou said, ‘Do you realise how many young men would cut their right arm off for this?’ I signed pretty quickly. Then they signed Jean-Pierre Beltoise. It was going to be a three-car team. I went home to Australia for Christmas thinking I’d cracked it. But on the way back I picked up a Daily Express at Heathrow. Its back page said ‘BRM signs Lauda’. That was a shock.

“Surtees, a lovely bloke socially, was a nightmare to drive for“

“I did the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch in March because ‘Regga’ had burned his hands at Kyalami. I qualified on the front row alongside Niki and Beltoise and was running third 10 laps from the finish when Clive Santo’s F5000 car took me out. I also did the International Trophy at Silverstone: a freezing, windy day. When a load of sleet blew across the track during practice I hit the barriers at Becketts. During the race the handling was terrible. We found out afterwards that a shock had been damaged in the crash.

“Nevertheless, I enjoyed a busy season of testing for BRM and being well paid for testing for Firestone and John Wyer’s sports car squad. The downside was that my contract prevented me from driving for another F1 team through 1973 and possibly 1974. All momentum was lost as far as F1 was concerned.”

You would drive for strong characters in F1: Mo Nunn, Hill and Surtees. All were ex-racing drivers. Help or hindrance?

VS: “They were very different personalities. However, I’m sure that ex-racing drivers who later in life design, build and run their own cars are unable or unwilling to admit that the car is the problem and inevitably feel that if they got back behind the wheel that they could do a better job. And you can’t drive for someone who rates the car and not the driver.

“It’s doubly difficult if the team’s other driver is going well, like Tony Brise in the Hill at the 1975 Swedish Grand Prix. Usually I adapted pretty quickly. On this occasion I jumped out of an F5000 car in America, flew to the UK, sat alongside Graham in his plane to Anderstorp – and liked neither the car nor the track. It was very deflating to be off the pace in practice. You felt a bit of a tosser!

“Surtees, a lovely bloke socially, was a nightmare to drive for. The TS19 of 1977 had a wide sports car-type nose and was an understeerer. We lapped two seconds quicker testing at Österreichring with a nose with fins. When we got back to England, John was so… angry. That wing hadn’t been on his list of things to try. He sent me out in practice with the wide nose back on.”

You had diversified by then: sports cars and Formula 5000 in Europe, America and Australia. Wyer and Teddy Yip: same planet, different worlds?

VS: “Referred to as ‘Death Ray’, Wyer could be frightening. My first drive for him was Le Mans ’73. They put me in the Mirage at night so that Mike Hailwood and John Watson could sleep. I had done two stints before refuelling for a third. Going through Tertre Rouge I spun on marbles strewn on the track by another car. Hitting the Armco at an angle going backwards the car flipped. Disorientated and trying to find the master switch in the dark was not as scary as contemplating what to say to Wyer. Only years later did team manager John Horsman tell me that the engine had been about to drop a valve.

“Teddy Yip was a real character but could be difficult. One Friday night before an F5000 race at Riverside, he said, ‘Right, boys. Quick! We are going to Las Vegas.’ He took them off my car and flew them and myself there for the night – then flew us back the next morning in time for qualifying.

“Sid Taylor was running the F5000 cars and never had enough money. Things kept breaking. Eventually I tried to talk Teddy into letting Sid go – but they were an item even though he treated Sid terribly at times. In the end I couldn’t tolerate it any more. My racing was going nowhere with them.”

Schuppan played his part in bringing F1 to the streets of Adelaide, which hosted grands prix from 1985-95. He now lives near the track

Simon Bruty/Allsport

Porsche took nine out of top ten places at Le Mans 1983

GP Library/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The Schuppan 962CR was aimed at the Japanese market but it bankrupted Vern

Dan Gurney gave you your Indianapolis 500 chance in 1976. How easily did you adapt to an oval?

VS: “To begin with, due to the 12-degree banking, you felt like the car should be flying off the road. You couldn’t touch the brakes and any lift had to be minuscule to keep the boost up with that big turbo. And it’s uncomfortable. Without a neck brace of some sort you can’t hold your head up and you’re all bent out of shape by the g forces.

“The Indy drivers were cool guys, fooling around and poking fun. They were fantastic with me. Lloyd Ruby came across with a wide belt with a big handle to ratchet it and told me to pull it down tight until I couldn’t move. And after I had qualified, Mario Andretti walked past and said, ‘Hey, nice job.’ A compliment from one of my heroes.”

Indycars would mirror your F1 career somewhat, with partial campaigns and one-offs for teams running different makes. Was that frustrating?

VS: “Though it had been a one-off with Dan, I was hoping to get more races because of it. The problem was that many of the business people buying a car to do Indy knew nothing about racing. I drove for the Wysards in 1977 and won the ‘Jigger’ Sirois Award for the unluckiest driver who didn’t make the race. The crew chief was an old boy who missed me on the watch and waved off my first attempt to qualify. The water pump failed on my second. And they forgot to fuel the car for my third; I ran out on the fourth and final lap.”

“We had led for 19 hours when the left-hand door blew off“

Is that why you decided to go it alone?

VS: “I reckoned I could do a better job than many of the small teams. In 1980 I had been in Tom Sneva’s back-up McLaren and couldn’t believe how good it was. Tom crashed his new ground-effect Phoenix and needed my car: starting from last, he finished second. McLaren had stopped racing at Indy but still had an M24 sitting in Detroit. I bought it and ordered a new Cosworth engine for 1981. Unfortunately, it didn’t handle anything like as well as Tom’s had and I scraped into the race.

“I had asked John Horsman to help run the team and he decided we were not getting enough downforce. The night before the race he cut a chunk off the rear wing’s trailing edge and raised it by that amount. They didn’t want to tell me what they had done. He came on the radio early: ‘How’s the car?’ To his relief I replied, ‘Good.’ It was after that race that I got the call from Porsche.”

Schuppan on his way to victory at Oran Park in 1976 in the Lola-Chevrolet T332 of Theodore Racing

Fairfax Media via Getty Images

Was Porsche the sort of team you could have done with earlier in your career?

VS: “Porsche was different. With Wyer, you had to memorise all the information all of the time so that Horsman could write it down. Porsche never even asked how the car felt. They had such confidence that they had got everything right. Very German.

“The 936 of 1981 had been pulled from the museum and fitted with a modified version of the engine originally destined for Indy. Its spaceframe with heavy-duty welds looked awful compared to the tidy aluminium monocoque of the Mirage – but it was the best sports car I had driven.

“The right-rear let go at 236mph on the Mulsanne Straight during practice. It was the first time they had used tyre pressure sensors: there were four warning lights on the dashboard. I told the Dunlop guy that there had been no warning and he admitted with some embarrassment that the blowout was caused by one of the sensors coming off and going through the tyre.”

Did you think you would never win Le Mans: third, fifth and second twice? Even when you won in 1983 in a Rothmans Porsche 956, you almost didn’t.

VS: “We had led for something like 19 hours and I was in the car when its left-hand door blew off after the Mulsanne Kink. The first repair utilised an aluminium strip riveted across the top of the door and roof. The second, demanded by officials, involved punching a hole in the roof and a buckled strap so that the driver could still open the door if necessary. It held but didn’t fit well and the airflow over the intercooler was affected.

“[Co-driver] Hurley Haywood and I were called to the control tower to await the finish and our victory celebration. There, we saw on a TV screen smoke pouring from the left-hand cylinder bank. I’d handed the car over to Al Holbert for the last 30 minutes and warned about the rising temperature. He told me later that the engine had locked exiting Arnage on the last lap and that he had dropped the clutch, which thankfully freed the engine and just got him home.”

Were 956 and 962 big steps up?

VS: “My first experience of a ground-effect car; the early 956s had very heavy steering and the faster you went, the more grip you had. Going through the long right-hander onto the pits straight at Fuji was so fast, the steering so heavy, it was hard to believe how the tyre stayed on the rim.

“Nova Engineering, the best team in Japan, approached Porsche about buying a 956 and Helmuth Bott asked if I would like to drive it. Jetting back and forth from the UK I won the Japanese championship in 1983. By late 1987 I found myself racing in Japan against my own Porsche team. I can’t believe they allowed me to do that.”

“We lost virtually everything and I needed a break“

Now you were the driver running other drivers. How would you judge yourself?

VS: “Pretty good, I think. I had enough experience to know what drivers want. And I had picked mine because I thought they were the best: Jean Alesi, Bob Wollek, Johnny Herbert, Brian Redman, Derek Bell, Geoff Brabham, Hurley Haywood, Price Cobb, Kenny Acheson, Emanuele Pirro. If a driver told me there was a handling problem, I believed him.”

Your Le Mans victory led to another intriguing phone call…

VS: “Our state premier John Bannon hosted a business lunch in my honour. There he announced that Adelaide was going to run a grand prix. Out of the blue. The government official put in charge was John Mitchell, who called to ask if I knew Bernie Ecclestone: ‘What’s he like? We have offered to fly him out, roll out the red carpet, but he’s not returning our calls.’ As I was about to return to the UK, John asked if I’d talk to him.

Brabham and Bob Jane, who owned Calder Park Raceway near Melbourne, had already spoken with Bernie, so he said to me, ‘You must be the only guy in Australia who doesn’t know that I’m not interested in a grand prix in Australia.’ I told him about Adelaide even so: a street race in the middle of a city, full financial backing from local government and city council, and beautiful stately homes lining the circuit. At the end of all that he promised to take a look at it.”

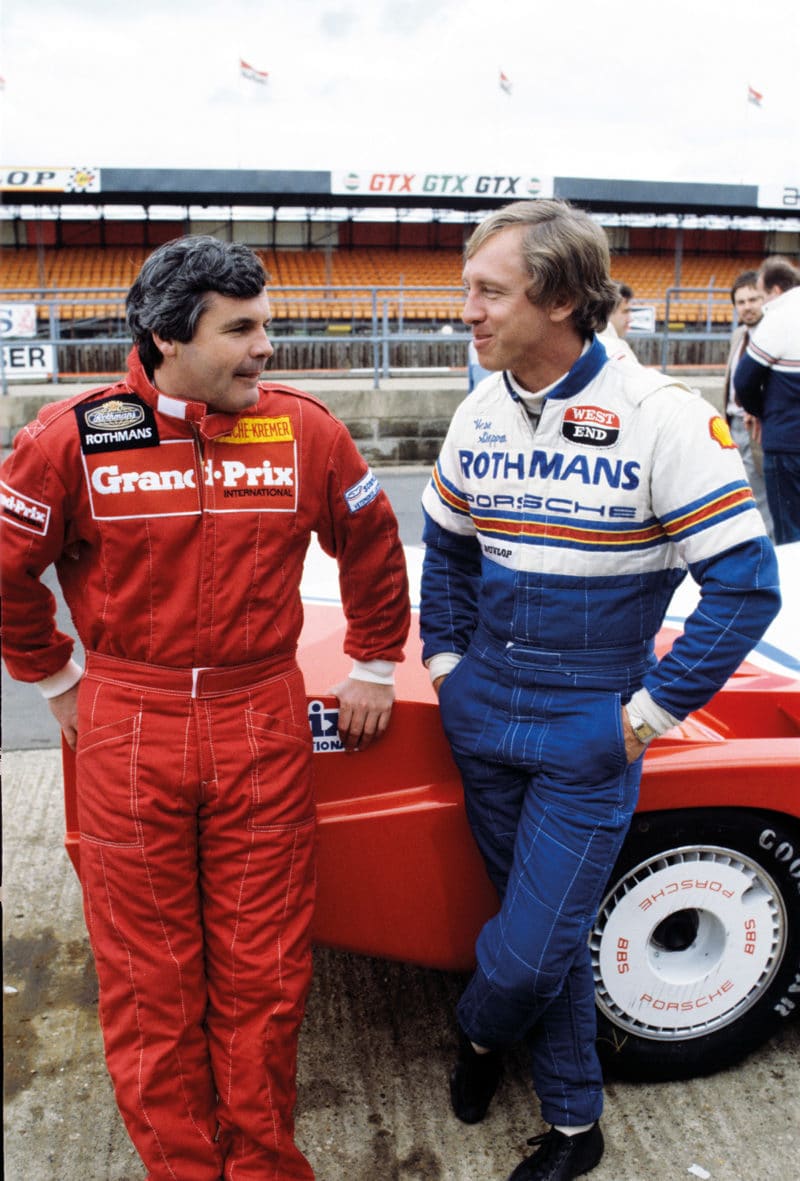

With team-mate Alan Jones at the 1983 Silverstone 1000Kms

Mcklein/Reinhard Klein/Colin McMaster

Your 962 road car project was less successful. What is your side of the story?

VS: “Japanese investors approached me about building a street-legal version of a Le Mans-bodied 956. I agreed it could be done but said we would probably have to do 25 cars to make it viable. We developed one of my cars as a mule, met the emissions standards and were tooled up to start. Then they decided they wanted a more practical GT-like car, which set the project back by 18 months.

“When the financial crisis developed in Japan the investors informed me that they would not take delivery until each car had been sold. They literally turned the tap off. I went to Japan and persuaded them to take 10. They reneged on that and said they would take three. In order to stay in business and pay our creditors, I asked for three letters of credit: £350,000 each, to give to the creditors. They flew over to inspect the cars, which were booked on a British Airways flight for the next day. Their lawyers then persuaded a High Court judge in an emergency meeting delayed until that morning that they had the right to another inspection.

“I was given a court order and rang BA: ‘You want us to bring back a Jumbo that is taxiing now, full of passengers, and unload it – and you can’t tell us who is going to pay for it?’ As soon as it took off, those lawyers phoned Barclays and told them I was in contempt of court and not to pay out on those letters of credit. They went out of their way to bankrupt me.

“We lost virtually everything and I needed a break from the UK. I met Stefan Johansson, who asked if I would set up an Indy Lights team. When his sponsor’s first cheque to me bounced, I told him it wasn’t going to work. He offered a half-share of the company.”

Did discovering Scott Dixon ease the pain?

VS: “New Zealand racing driver Kenny Smith, an old pal, had told me that Scott was the best young driver he’d seen and we arranged an Indy Lights test at Sebring. Heading into the first corner Scott got in the way of Lights driver Felipe Giaffone, who went by him shaking his fist. On the next lap, at the same corner, Scott outbraked him and drove away from him. Shortly after that I flew to New Zealand and negotiated a 10-year contract for Johansson Motorsports. Unfortunately one of our main sponsors pulled out and to keep going I agreed to forego my retainer until things picked up. I was owed a lot of money by the end of 1999 and walked away from motor racing.

“A few years later the organisers of the classic Adelaide Rally asked if I knew of a former Ferrari grand prix driver who might be interested in taking part. The only one I knew was Stefan and I was persuaded to make the call. He liked the idea, we buried our grievances and he came to Adelaide. These days we’re good friends. You have to move on.

“I don’t look back and think, ‘Why did I do this or why did they do that?’ There was a good reason why Lauda was in that BRM. It’s just how motor racing is. Mainly I think those years were great and, with a wonderful family and lifestyle, things still are.”