Racing while paralysed: Sam Schmidt's McLaren controlled by his head

A crash in 2000 left Arrow McLaren SP co-owner Sam Schmidt paralysed. Now technology has given him the opportunity to race again in a converted supercar and Adam Hay-Nicholls gets an exclusive - and incredible - test drive

Sam Schmidt was an upcoming IndyCar racer when a 200mph crash ended his career. Experts thought he would be dead within three to five years

Scott Robinson

Sam Schmidt was on the verge of becoming an IndyCar title contender before he crashed his Treadway Racing G-Force in January 2000, testing at the Walt Disney World Speedway near Orlando in the run up to the Indy Racing League season opener. The 200mph impact broke the then 35-year-old’s back and left him quadriplegic, paralysed from the neck down. It hasn’t stopped him from driving supercars. The American has helped create a one-of-a-kind McLaren 720S which he can steer with his head and accelerate and brake with his breath. And he let me have a go.

From the outside the 720S Spider looks normal – well, normal for a 212mph McLaren – and behind the seats is a standard-issue 4-litre twin-turbo V8 developing 710bhp. But Arrow Electronics – a Colorado-based Fortune 500 company – has fitted optional extras.

Being quadriplegic means that Schmidt has to be craned in to vehicles, hence using a 720S Spider

Arrow Electronics

Inside is a steering wheel on the left and pedals, because a co-driver is required just in case something goes wrong. I join Sam as his co-driver for a few laps of the circuit before he hands his seat over to me (I only had to grab the wheel to avoid the grass a couple of times!). On Schmidt’s side, there are no obvious controls and I take my place on the right-hand-side.

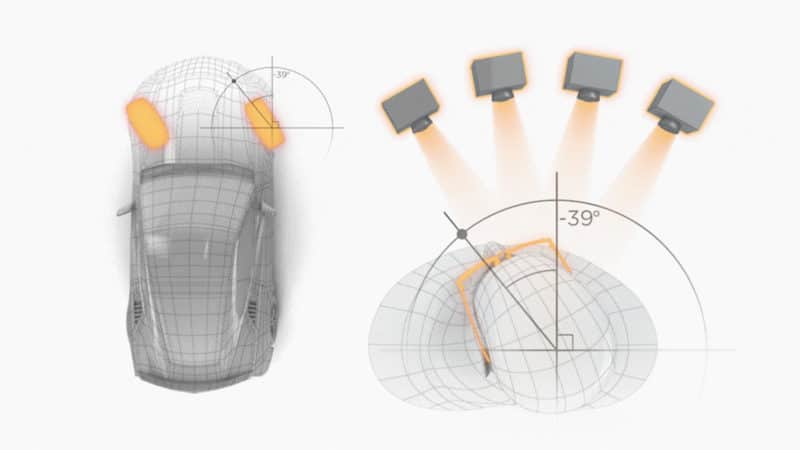

Ahead of me, on the dashboard, are three infrared cameras. I don a helmet peppered with 11 dots. These are reflective markers and they work the same way as CGI, where green-screen actors wear bodysuits with ping-pong balls attached. The car’s cameras measure the angle of reflection. To set it up, an engineer waves a ‘calibration wand’ in front of my face. It’s looks like a window-washing squeegee.

Infrared cameras in the McLaren track the driver’s head movement and the car steers accordingly. At present, a co-driver is also in the car who can take control should any problems arise

My helmet is, in effect, the steering wheel. When I move my head a couple of inches to the left and right the wheels move accordingly. The helmet contains a plastic pipe, like a straw, which is inserted into the mouth. The car is in neutral. When I blow into the tube, the engine revs. The straw has a negative and positive sensor which, via software, adjusts the pedal angles. To brake, you suck.

My co-driver engages gear and I carefully exhale, being mindful to look ahead up the track to Goodwood’s first corner and not be distracted by anything peripheral. Off we go.

Acceleration is achieved by blowing into a pipe – although, as we found, saliva can clog the system. Even so, the semiautonomous mobility system (SAM) means Schmidt can race at speed once again

Once you’ve blown into the tube and are accelerating you bite the end of it to maintain speed. Braking is difficult to gauge and requires a bit of practice, as one tends to pull up rather abruptly with the slightest inhalation. The steering seems to have a half-second delay, so you need to factor that in when taking the turns. The line of sight that one uses is not dissimilar to that which a racing driver would take normally, but you can’t see beyond to the next corner in the same way.

My first couple of laps are pretty good, on the straight bits at least, hitting around 80mph in places. However, excess saliva is a problem; the tube gets full of spit and I’m struggling to apply power. By the end of this short session, my cheeks are red from blowing so hard. It’s like I’ve inflated a dozen air mattresses.

Braking on the car is controlled by sucking a pipe. Schmidt has been working with Arrow Electronics since 2014 on the ‘sip-and-puff’ system of driving, which was used in the project’s previous cars – including a Corvette

Arrow Electronics’ Joe Verrengia, director of the SAM (semi-autonomous mobility) project, describes Schmidt as “an astronaut for the disabled community”.

“The desire to get out of the wheelchair and push the limits has been there since day one,” says Schmidt, 58, back in the pits. At the end of 1999, Sam was on a high. He was a rising star in the Indy Racing League, and won his first race late that season, in Las Vegas, after 27 goes. He also achieved two second places and a third. “I was one of the favourites to win the title in 2000,” he tells me. “I’d just won my first race. I had a six-month-old and a two-year-old, and a beautiful wife of seven years. Everything was cruising along splendidly. Then, at a pre-season test in Florida, I hit the wall at 200mph and blew apart my C3 and C4 vertebrae. I couldn’t breathe for well over four minutes. Fortunately, the safety crew got me resuscitated and into a helicopter. My wife was told if I made it through the night I’d be on a ventilator and in bed for the rest of my life, which might be three to five years.”

The accident turned the Schmidt family’s lives upside down, but Sam defied the grim prognosis. His wife Sheila found an ‘aggressive’ rehabilitation programme in St Louis, where his neck was stabilised and he was weaned off the ventilator. He had professional athlete insurance. After six months, he was able to leave hospital and continue his rehabilitation at home in Nevada. “I quickly came to the realisation that I had it pretty good,” says Sam.

While at Goodwood, Schmidt exhibited an exoskeleton suit devised by Arrow Electronics with robotic engineering researchers at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee

Arrow Electronics

In September 2000, he visited the Brickyard to watch its inaugural Formula 1 grand prix and meet fellow quadriplegic Sir Frank Williams. “His main message was: focus on your purpose in life and don’t give up until you get it. Frank was helpful.”

The following year, Schmidt established his own racing team, which would go on to score seven Indy Lights championships and win 10 IndyCar Series races so far. He’s yet to reach his goal of winning the Indy 500, but the team – now christened Arrow McLaren SP (he’s the ‘S’) – finished second this year. His team also secured pole position at Indianapolis in 2011, which Sam describes as “like crack – you want more”.

His energy is inexhaustible and his optimism inspiring. “If you sit around and do nothing you’ll get nothing in return. If you find your passion, if you have the right attitude and you’re willing to put the time in, whether that’s exercise or studying or whatever it takes to achieve your goal, you can get there.”

Schmidt showcased Arrow’s SAM McLaren at low and moderate speeds on Goodwood’s incline, reaching 115mph

Arrow Electronics

Schmidt at Goodwood in the specially adapted McLaren 720S Spider

Arrow Electronics

Schmidt winched into position at Goodwood

Arrow Electronics

Running a multi-million-dollar business seems all the more incredible when one learns it takes Schmidt three to four hours just to emerge from bed, get washed, eat breakfast and leave the house every morning with the aid of his full-time nurse. He takes over 100 commercial flights a year, with the inability to move any of his limbs. He needs to be craned from his wheelchair into any mode of transportation, including the McLaren – hence why he has a Spider with retractable hardtop.

Sam’s determination was, he says, always there. “I don’t think you get to the top levels of motor sport without having perseverance and determination. My last name wasn’t Foyt or Unser or something. I had to find how to get there, to the Indy 500. That was my life’s goal. I got there just through sheer grit. This [challenge] is very much the same thing, although solving spinal cord injury is something that’s going to take a lot of time, energy and money, resources, and we’re still working on it. We’ve made more progress in the last five years than the previous 20. It can be frustrating because it is so slow. But projects like this [SAM car] really re-inspire me as far as the capabilities of technology and what you can accomplish if you get the right team.”

Schmidt with the paralysed three-time 500cc world champion Wayne Rainey at the Festival of Speed. Rainey rode his 1992 Yamaha YZR500 at Goodwood, which had been specially modified

Arrow Electronics

The SAM project started nine years ago, and was christened with the acronym before Sam Schmidt was involved. Arrow Electronics launched it as a corporate social responsibility (CSR) not-for-profit programme to innovate technological benefits for disabled people. You don’t even have to be a petrolhead to acknowledge that driving equals freedom. Joe Verrengia, who is responsible for Arrow’s CSR programmes, heard about Schmidt and sent him a text to see if he’d like to be involved – as an astronaut. The driver texted back: ‘Don’t know you guys, but if you build it I’ll drive it.”

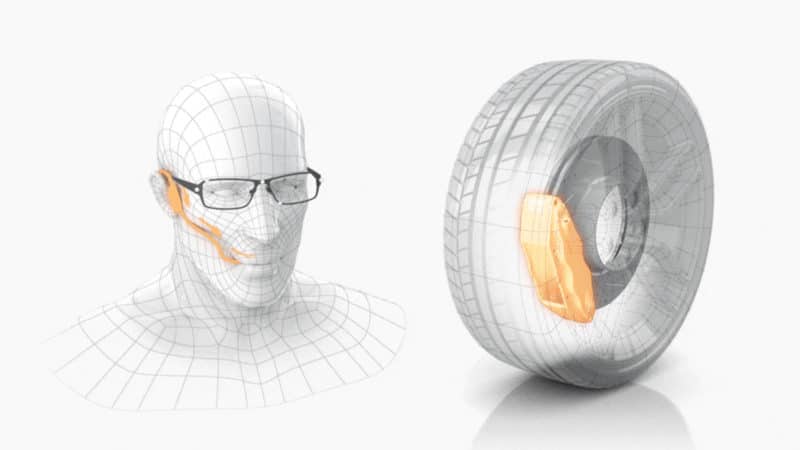

The McLaren is the second SAM car, having recently replaced a Corvette which had been developed over many years. Originally, Schmidt had a system where the car would accelerate when he put pressure on his headrest. To brake, he would bite. He started with ovals where you only need to turn left. Fourteen-turn road courses came later. Given Sam’s head has become a joystick, it begs the question – what happens if he sneezes? Did you know that quadriplegics cannot sneeze?

A young Schmidt

Sam Schmidt

Of course, he’d rather still be an able-bodied racing driver than a team owner and quadriplegic pioneer. “Today I’d probably be racing some nice vintage race cars”, he says, looking around the Goodwood paddock. “You never know where life is going to take you, but it’s been a great experience being a team owner, challenging, but like anything else it’s about putting the right people in the right places and letting them do their job.”

“In some ways,” he says of this Arrow project, “it’s better than racing because this is driving with a purpose. This technology can help people with their daily living. I’d love to see it help people get back to work. Maybe a farmer driving his harvester or a forklift or something. Because a lot of times that’s all people are asking for, the ability to put food on the table, be the breadwinner.”

Verrengia adds that the technology is not for sale, “but I would give it to you for free if you have an application that’s interesting”.

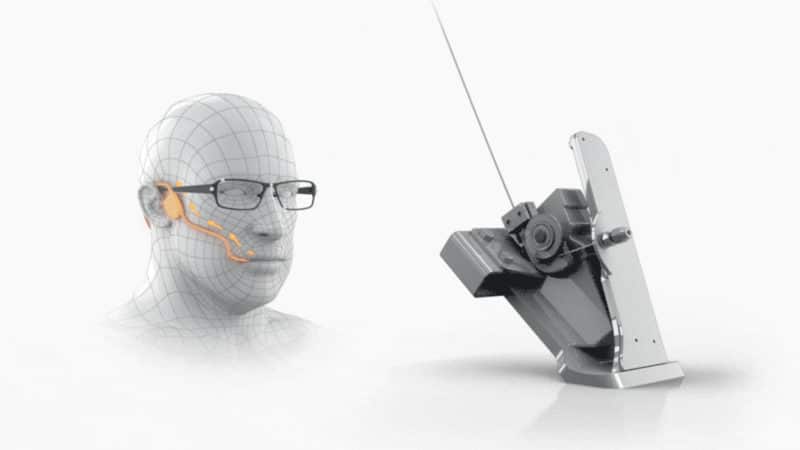

Schmidt is not restricted to closed circuits. The state of Nevada has given him a unique driving licence which allows him to drive on public roads. He doesn’t need to wear a helmet either, as Arrow has fitted reflective dots to a set of Oakley sunglasses which take care of the steering just the same.

It is hoped Arrow Electronics’ tech could help people with disabilities “put food on the table”

Arrow Electronics

The McLaren is in a constant state of development and its three NaturalPoint 13W Prime wide-angle IR cameras are soon to be replaced with a more advanced artificial intelligence camera, which will be more precise and offer greater security through facial recognition – although if someone got in this car to steal it they’d probably find the controls unfathomable anyway.

The constant R&D reminds Schmidt of how things used to be when he was pushing for better lap times. “They keep advancing the car and I keep showing up to try and push it forward. It’s a great collaborative effort and it feels like I’m a professional driver again, because I give my input and someone else has to find the money to make it happen.”

Driving his SAM car up the hill at the Festival of Speed is one of many bucket-list items Schmidt has ticked off since his accident. “I’ve controlled a sailboat with my chin, swum with sharks, flown a hot-air balloon, jumped out of an airplane with my kids – me and my kids try and do some challenge together once a year. They’ve had plenty of rides in the car.”

Does he get as much of a thrill driving the way he does now? “You know,” Sam says, “I think it’s still a thrill.”