The ones that got away: 8 great lost rally cars

It isn’t just track cars that can end up on the cutting room floor. These rally radicals from the likes of Audi, Peugeot and even Proton might have taken the world by storm, but as Anthony Peacock reveals, they were destined for lesser things

Part house brick, part Porsche 911 in styling terms. Audi’s abandoned Group S effort wasn’t pretty, but boasted up to 1000bhp

Volkswagen Polo WRC (2017)

The real shame about a few of these unrallied cars is that they could have become world-beaters. In the case of the 2017 Volkswagen Polo WRC, there’s no doubt about it.

The last Polo was built to the exciting new 2017 WRC regulations, when the cars sprouted bigger wings, brasher attitude and a lot more power. Volkswagen had been the dominant team (with Sébastien Ogier) since 2013, winning 43 of the 53 rallies it entered. Which made it all the more shocking when the company suddenly canned its WRC programme in November 2016 following the infamous emissions scandal. By that point the new Polo WRC was only a couple of months away from its competition debut in Monte-Carlo, so virtually complete.

Dominant in rallying for four years, Volkswagen’s success would have surely continued with the beefier 2017 Polo. The car, wearing a Red Bull zebra camouflage, was tested by Marcus Grönholm

Marcus Grönholm was one of many drivers to test it subsequently and described it as the best rally car he had ever driven. Enough said.

Lancia Delta ECV

Believe it or not, there was actually something even faster and crazier than Group B that was originally planned to replace rallying’s most outlandish era. And that was Group S, which was intended to come in for the 1988 season – to respect a five-year period of rule stability that was promised with Group B. But of course Group S never came to fruition thanks to a series of fatal accidents in Group B, which convinced the sport’s rule-makers that a more powerful successor to those regulations might not be a terribly good idea.

Nonetheless, many manufacturers already had their cars prepared: first and foremost Lancia with the Delta ECV, which stood for Experimental Composite Vehicle. It was 20% lighter than the S4 it replaced and was the first rally car to use computer-aided design. Power came from a revolutionary ‘Triflux’ twin-turbo engine, which was nonetheless incredibly hard to drive, with very little torque at low revs followed by a wall of power as those turbos kicked in. The ECV (and subsequent ECV2: an evolved version) never competed but it remains a monument to what might have been.

Audi Quattro ‘RS002’

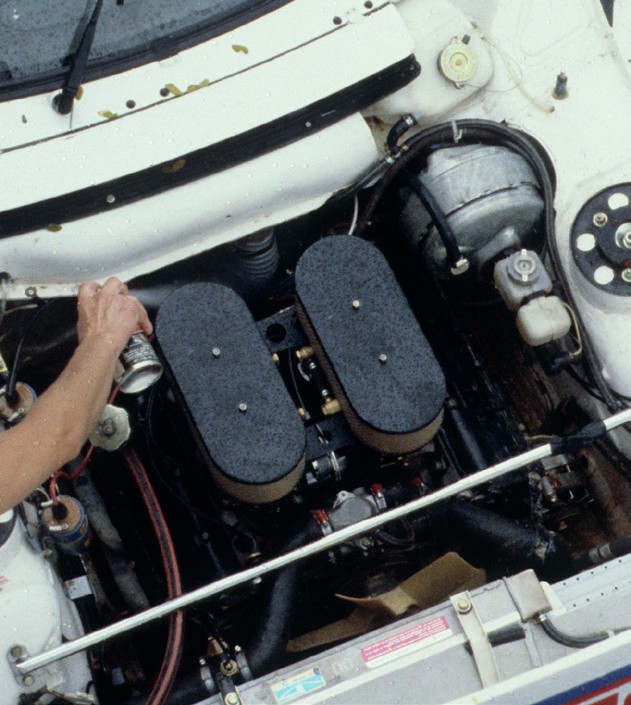

This was another Group S special and what it lacked by way of looks it made up for in sheer effectiveness. It resembled an aerodynamic house brick that had mated with a Porsche 911, but that unprepossessing exterior hid around 1000bhp, according to some people.

The ‘RS002’ – although it was never officially named – was a top-secret project. Rumour had it that not even Audi’s top bosses were aware of it, and testing was moved to an obscure corner of Czechoslovakia to avoid spies, both from within the company and outside it.

“What if?” – that’s the question you have to ask about the top-secret Group S mid-engined Quattro

Audi’s rally engineers such as Roland Gumpert knew that the days of the front-engined Quattro were numbered, faced with the mid-engined rally specials that were in vogue as the 1980s progressed. Audi’s top management, however, wanted to stick with a concept based on the road cars for marketing purposes. So you can imagine their fury when they found out what was being secretly worked on.

The suits instantly ordered all the prototypes to be crushed – but there was thankfully just one survivor, which now lives in Audi’s museum.

Proton Putra WRC

Proton has competed with great success in Group N (effectively as a rebadged Mitsubishi) and to some extent in Super 1600, with the diminutive Satria – which was even driven by the great Gilles Panizzi on the 2010 Sanremo Rally. But although the partially state-owned company from Malaysia never competed at the very top of the sport, it came incredibly close in 1998 thanks to this remarkable Impreza WRC lookalike.

The family resemblance is no coincidence, as the Putra WRC was also built by Prodrive. It never rallied, but with so much Impreza DNA having gone into it, it could eventually have been incredibly successful. It might even have entirely transformed the image of the brand, just as rallying did with Subaru. But that’s all ancient history now – although it was only recently that Proton claimed paternity of the Putra WRC project at all, having previously denied its existence. The two prototypes now reside in Proton’s motor sport department.

Toyota MR2 222D

Toyota has been one of the most prolific manufacturers in rallying throughout the Group A and now WRC era, not to mention Group B with the Celica Twin Cam. But the Japanese manufacturer also prepared a Group S challenger, based on the MR2.

It was a logical choice, with its standard mid-engined layout perfectly translatable into competition. The 222D project actually bore little resemblance to the standard MR2 in the end, with a much wider track and the characteristic pop-up headlamps replaced by more reliable fixed units.

Only two Toyota 222D development prototypes exist today; this one is at Toyota Motorsport in Cologne

A variety of engines was trialled, as well as both two-and four-wheel-drive layouts. One of the test drivers was Ove Andersson who said: “You never knew what it was going to do. It could swap ends at any time and without warning.”

A total of 11 prototypes were rumoured to have been built before – to Andersson’s relief – the whole Group S idea was canned.

Ferrari 288 GTO

A Ferrari had of course finished on the WRC podium before, courtesy of Jean- Claude Andruet on the 1982 Tour de Corse in a 308 GTB. The 288 GTO was in many ways the heir to that car in the Group B category – with the crucial difference that it never got to compete. Powered by a 2855cc V8 twin-turbo engine, the power-toweight ratio was phenomenal, although it was only meant for asphalt. The 200 road-going examples were built for homologation requirements by June 1985 but with Group B cancelled before the end of 1986 there was nowhere left for it to compete. So the 288 GTO was sold to Maranello’s loyal customers instead, gaining a following that probably surpassed anything it would have achieved in rallying.

Peugeot 305 V6 Rally

A few years before the introduction of the fêted 205 T16, Peugeot made something of a false start by deciding that its designated Group B car was in fact going to be the 305, a model that had been in production since 1977. But the heart of it was somewhat older: the V6 engine and running gear from the 504 Coupé rally car, a rugged warhorse that had proved to be an effective weapon on African endurance rallies.

Once highly regarded by French taxi drivers, it seems unthinkable that the dreary 305 could have won the hearts of rally fans quite like the 205

The end result was an odd-looking machine that didn’t resemble the staid 305 at all, but a change in management put the brakes on the project. This was far from bad news, as the season for which the 305 V6 Rally was meant to be introduced – 1983 – was also the debut year for the 205 road car. In the latest management reshuffle, a certain Jean Todt was put in charge of Peugeot’s competitions department, and he had an idea…

Ford Escort 1700T

With the prospect of having an uncompetitive car, Ford pulled the plug on its rear-wheel-drive 1700T, and so began the RS200 venture

Perhaps the most famous of the unrallied cars was the Ford Escort 1700T, the car that had the unenviable task of taking over the mantle from the Mark I and Mark II Escorts. The road car that replaced them was front-wheel drive, but for the mooted rally version, only rear-wheel drive would do.

It was designed as a Group B challenger, but unlike many of its four-wheel-drive or composite rivals, the new Escort was much more straightforward: it used a modified steel body from the XR3 road car, and a 1700cc turbocharged engine that had its roots in the BDA unit used so successfully by its forebears.

Malcolm Wilson, who now heads up M-Sport, did much of the testing and the early form looked promising. But production of the 200 road cars required for homologation was hit by delays. And those delays proved crucial, as by March 1983 Ford’s bosses realised that their new rally car was ultimately unlikely to be competitive against bespoke Group B machinery such as the Peugeot 205 T16. Something more specialised was required, and that was how the four-wheel-drive RS200 was born – once the plug had been pulled on the unfortunate Escort.