A light upon the Shadows — The magnificent machines of a man of mystery: Book review

Don Nichols’ Shadow team was more than just a curio of F1 history. A new work reveals the full story, says Gordon Cruickshank

Jean-Pierre Jarier was a star for the team, even if 1975’s DN5 was troublesome. He’d score a season best of fourth at MontjuÏc in Spain

Getty Images

So you want to write a biography? You’ll be well served if you find someone who achieved something notable yet has mystery, even notoriety to his back story. And if that story begins with a tornado tearing a car apart and your infant subject being hurled into the woods and lost for hours then you’ve hit the ground running. That’s Don Nichols, creator of Shadow cars and of many a myth, who did nothing the ordinary way. No wonder Chapter One of this hefty work is titled ‘Born to Battle’.

Pete Lyons reported on Shadow’s Can-Am and Formula 1 entries in their time so he has an insight into the cars on track, but more importantly Don Nichols sat down with him late in life to create this handsome biography, in the characterful setting of the old man’s warehouse stuffed with the relics and reminders of his racing career. Thus we have the first-hand account interweaved with the written record, and if some of Nichols’ stories sound stretched, well, Lyons has done as much as he can to confirm things…

And battle is how the story proceeds; after going early into the army he was a Pathfinder paratrooper, landing in the first minutes of D-Day and battling on through the Battle of the Bulge to end of war demob – after which he re-enlisted. It’s this period in Japan through the Cold War that raises the rumours of clandestine activities. Asked to talk about this, Nichols tells Lyons “I can’t talk about that. Not proper to discuss it.” Which may or may not confirm anything at all. But it does add some sauce to spice an entertaining story not only of racing but of engineering artistry. For it seems Nichols viewed his work as engineering art – he is proud to show off to Lyons parts of his cars that he feels deserve admiration.

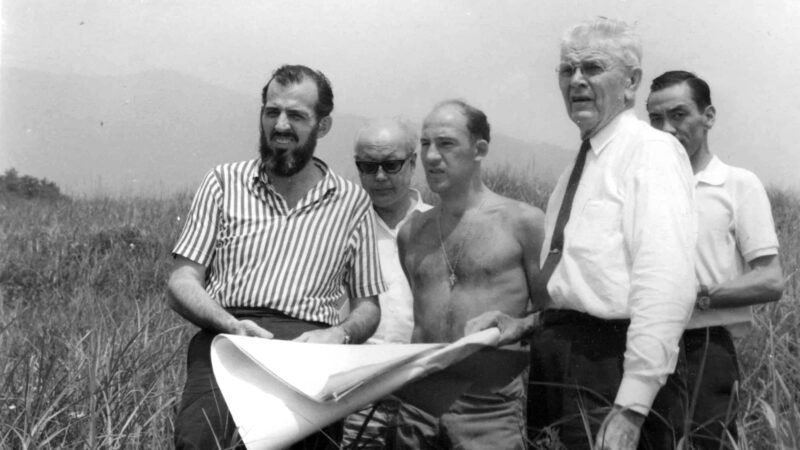

Don Nichols (left), Stirling Moss and NASCAR track designer Charles Moneypenny planning Fuji

Pete Lyons

That Japan period, in which he made his first fortune, also cemented a connection with racing. He dabbled behind the wheel, but more significantly sparked off what became Fuji raceway, attracting IndyCar, Can-Am and Group 7 events, even hiring Pedro Rodríguez to drive his Lola. He was never going to do things the small way. But more mystery surrounds what happened to his business; he just says “It wasn’t advisable for me to go back to Japan”.

Back in the US with a full wallet Nichols, open to ideas, meets Trevor Harris who has this crazy plan for a lowline Can-Am car. One of the pleasures of this book is the richness of the visual material: Nichols appears to have kept everything, from complete cars and engines down to the paperwork – his racing licences, drawings and concept sketches of the original AVS Shadow, so low you could trip over it. There are also scores of great photographs of the early builds illustrating the horizontal steering wheel and bazooka air intake that never reached the track.

Lyons continues with the same depth not only from Nichols’ own recollections but also others involved, such as Peter Bryant, who took over as designer after the Can-Am kart flopped. Along with generous details of the next car, Bryant also makes an interesting comment about the man he was dealing with. Nichols kept playing The Impossible Dream from the Don Quixote musical, and Bryant decided that he saw himself as “a kind of Quixote, tilting at windmills and trying to reach unreachable stars”. Well, as Lyons makes clear, Nichols sometimes got close.

As we proceed through the increasingly conventional Can-Am cars (running on UOP’s unleaded fuel stiff with eye-watering acetone) towards F1, the facts keep coming – interviews with designers, crew members and suppliers, workshop photos of the build process, and promotional material, delivered with Lyons’ lively writing. Including the detail that it was Jackie Oliver, the team’s Can-Am driver, who turned Nichols’ eyes towards Europe and F1. You can find the GP results anywhere – promising moments, disheartening failures and a single victory – but it’s what was going on in the background that’s fascinating. Such as the proposed WSC machine Tony Southgate designed (the wind-tunnel model is illustrated as Nichols kept that too) and his comments about the Man in Black, who steered his huge black Cadillac around Europe. Southgate reckons the symbol of the caped figure “suited Don down to the ground, but the only comment I got from him was that there was a once a cartoon comic figure called ‘The Shadow’, at which point he got a bit embarrassed and went silent”.

That black livery was excellent branding. In the paddock the vast UOP Shadow artic dominated rival team transporters and helped radiate the sense of a wealthy outfit, though in truth money was tight. Southgate says: “you never knew where the money was coming from”. Yet Nichols is quoted saying “we were spending more money than most – two or three million a year”. Another dichotomy is Nichols’ own character. Some saw him as open and approachable, others as secretive, aggressive and ready to do you down in a deal. There are plenty of references in the book to arguments over who owned what, and of course the ‘Sharrows’ affair when Nichols sued Jackie Oliver’s new-born Arrows for copying his design. Oliver is open about it, but all Nichols will say to Lyons about Oliver’s departure is “I don’t blame him. I couldn’t pay him”. But Nichols battled on, always fighting on many fronts at once – F1, Can-Am, F5000 and, back at the skunkworks, on electric vehicles and military Jeeps, and who knows what business deals. One colleague reports “his business ethics were terrible”. But he achieved plenty, drew drivers such as Redman, Follmer, Jones and Pryce, and always provided great copy. This makes a great read, and as Nichols died in 2017, it’s probably also the final word.

Shadow—The magnificent machines of a man of mystery

Shadow—The magnificent machines of a man of mystery

Pete Lyons

EVRO | ISBN 978-1-910505-49-6

Shadow—The magnificent machines of a man of mystery

Shadow—The magnificent machines of a man of mystery