F1 restoration: Jordan 195

Restoration of an ex-Barrichello F1 car is nearing completion and owner Warren Stean is planning its first public demonstration I don’t quite yet have a fully rebuilt and dyno-tested engine,…

It’s always the same when a fresh group of Formula 1 regulations is implemented. Cars appear slightly odd when the first publicity shots appear, but after watching for a few laps you swiftly forget that they ever looked any different. During the opening free practice session of 2009 in Melbourne, however, one car continued to stand apart – not so much for its stance as for the way it was presented. Predominantly white bodywork, a few complementary flashes of fluorescent yellow, scarcely a sponsorship decal worth the name… The team might have been short of resources, but its performance reserves ran deeper than anyone might have anticipated. Jenson Button was on the cusp of winning six out of the first seven races, the springboard to a successful world title conquest that even today, a decade on, stands apart as one of the great and most unlikely achievements in modern F1.

The sport has featured a litany of drivers who became one-hit wonders, but teams? There have been occasional bolts from the blue (newcomer Wolf winning its maiden grand prix at Buenos Aires in 1977, for instance), but nothing that has had the sustained impact of Brawn. It was a story that hinged on an improbable confluence of factors – one manufacturer pulling out, teams pitching in to assist a wounded rival and a top driver exploiting an improbably well-honed chassis while adversaries struggled to catch up… then clinging on to that early-season advantage as financial reality bit.

It’s a story that’s unlikely ever to be repeated at the top level.

In the formative stages of its genesis, the Brawn BGP 001 was destined to become the Honda RA109 – and there was little reason to suspect that would change. After a dismal 2007 campaign, Honda hired former Ferrari technical linchpin Ross Brawn to get its F1 project back on track – and with new rules on the horizon, the Englishman opted for a long-term view. “By the time I came on board,” he says, “the specification of the 2008 car was fairly settled, so my main focus was to restructure the organisation and get stuck into the 2009 programme. We felt there was no point pouring resources into the existing car because we had this big opportunity coming up on the horizon. I’d agreed a three-year deal on the basis that the first would be to build and assess, the second to show what we were able to do and then the third to try to challenge for the championship.”

Late in November 2008, however, Brawn and fellow team director Nick Fry were summoned to Honda’s UK office in Slough. “We were told very simply that they were shutting the operation down,” he says. “We’d had our budget approved for 2009 and everything was in place, so Nick and I really had no idea what lay in store. We were told to return to the factory, let everyone know and then shut it down. Before we went any further, though, we requested our legal counsel and the first thing they did was advise Honda that they couldn’t simply close the factory, because we had more than 700 people and these things require a formal consultation process, to look into viable alternatives. That bought us some time and we were able to start discussing the feasibility of finding a new owner.

“At first we certainly weren’t thinking about taking it on ourselves. That became more of an option when we saw the calibre of those who were expressing an interest in the team. It’s like the old Groucho Marx joke, ‘I wouldn’t join a club that would have me as a member.’ I wouldn’t have wanted to work for some of the people who were trying to buy the assets… It was apparent after a while that there were no serious potential buyers, they were all chancers.”

Eventually, it became clear that the cheapest, most elegant solution would be for Honda to provide a rudimentary budget for the year ahead rather than simply closing the whole operation. Brawn says: “The deal with Honda was, ‘Right, it will cost you X to close the company, pay off the redundancies and all the contracts that you’d be breaching, or we could carry on and take on that responsibility for less than X.’ It was a cheaper deal for Honda and, morally, put it in a much nicer position. It wasn’t great having to lay off 300 people, but we kept 400 and the team remained alive, so Honda effectively paid us a fee to take the thing on – and we had enough money to last the year. It was what I’d call a ‘survival plan’, certainly not a flat-out operational budget.”

With no future technical support from the former parent company, a deal was done to secure the use of Mercedes-Benz V8s – and that meant carving up parts of the original design. “On the Mercedes engine the output shaft was higher than that of the Honda,” Brawn says. “We didn’t have an opportunity to redesign the gearbox completely, we just had to sort of change the bellhousing to make it bolt on to a Mercedes V8. We certainly couldn’t look at changing the rest of the gearbox. The whole assembly – gearbox, rear suspension – was now 8-10mm higher than it should have been because we had to match it to a higher crank. That was probably the biggest compromise, but I don’t think the rest was too troublesome. Mercedes motor sport chief Norbert Haug was very helpful, but aware that his board was slightly nervous about our financial position. We told him not to worry and that we’d pay the whole amount up front, because we had our dowry from Honda so there was no reason not to do that and we wanted to build a good relationship. I think he was relieved when he received his cheque for full payment fairly early in the year.”

On March 6, 2009, little more than three weeks before the season-opening race in Australia, the team was formally rebranded as Brawn GP. “That wasn’t my idea,” Ross says. “Our legal counsel Caroline McGrory proposed it. We had a whole range of possibilities and I wasn’t keen on any of them – one was Pure Racing, which made me gag. We even looked at calling it ‘Tyrrell’ again, to honour the team’s roots, but that had complications for the Tyrrell family. Caroline suggested ‘Brawn’, other directors were keen, and I was hugely flattered.”

“Our times were disallowed because they assumed Jenson cut the chicane”

The team wasn’t quite ready for the start of pre-season testing – and Brawn admits that he and his colleagues were puzzled when they saw rivals’ lap times. “We had all our numbers,” he says, “and realised that either we’d missed something, or else we simply had a better car than anything else running at that time. We weren’t sure which, because there seemed to be such a disparity. The engineers kept poring over our figures and coming to the same conclusions, so we thought we’d see what happened.”

The answer was a pace-setting performance at the BGP 001’s first appearance in Barcelona, when Rubens Barrichello posted what would be the week’s fastest time. Before that, team-mate Button had also caught the eye with some searing laps. “I think our first few quick times were disallowed because they assumed Jenson must have cut the chicane,” Brawn says, “but for us it was a realisation that our calculations had been correct. Jenson was quick, yet saying that the balance needed some work. We were already running with a fair bit of fuel – but added more to quieten things down a bit. It was clear, though, that we had an advantage of one second per lap or more over the opposition, which is pretty unusual.

“You have to bear in mind that it had never entered our heads that we might be a title challenger. We were in survival mode just to get on the track. We thought we might be able to pull in some sponsorship if we could notch up some good results.

“That was our mindset, there was no thought about winning races, but as soon as we started running the car we realised the scale of the opportunity that was suddenly presenting itself.”

He knew, though, that the likes of McLaren, Red Bull and Ferrari had resources to facilitate a swift recovery. “There was nothing in our cupboard,” he says. “In F1, by the time you’ve run a car for the first time you usually know what’s coming along – you have all the targets for when you’re going to introduce upgrades. Classically, the opening European race in Barcelona is where you see the first big changes, but we had nothing – our car was our car and that’s all we had. We used two chassis for the first part of the season, built only three in total and managed just a few gentle upgrades here and there.

It was en route to Barcelona that Brawn strolled forward from about row 17 of an EasyJet Airbus to chat to fellow passengers, pontificating that he might in future have to stretch the team’s budget to embrace Speedy Boarding, for the sake of extra legroom. It wasn’t unusual to see Brawn and his colleagues using budget airlines during the season; on a return flight from Istanbul, EasyJet customers were surprised to find the previous afternoon’s race winner Button in their midst – and perhaps more so still when he voluntarily walked down the aisle with a rubbish bag towards the journey’s end, assisting with the cabin clean-up.

“We gained more recognition as the year went on,” Brawn says, “and British Airways started offering me complimentary upgrades, but of course people read that the wrong way. It was perceived to be, ‘Oh, they’re winning now, they’re starting to spend money,’ but that simply wasn’t true. It was BA that very kindly invited me to turn left when boarding and I should have had enough nous to realise that somebody would pick up on it and write a shitty article. I remember reading that I was ‘still travelling first-class’, but there was no way we would have paid for that. I wasn’t going to turn it down, though…”

Button’s role as a temporary cabin steward coincided with the end of his winning opening salvo. The BGP 001 remained effective into the second part of the season – Barrichello emerging triumphant at Valencia and Monza – but this was the era of 10 points for a win and eight for second place, so six victories from seven races (one of those with half-scores awarded, following the rain-enforced cessation in Malaysia) had earned the championship leader a cushion of only 26 points. That would be enough to protect him, but why did his performances tail off slightly during the summer?

“It’s an intriguing question,” Brawn says. “Getting the correct tyre temperatures was challenging, as ever, and there were a few races where we just couldn’t do that. We didn’t know as much about tyres as teams do now in terms of management and sensitivity. There are all sorts of tricks teams pull today to get tyres into their working range, but back then we sometimes just couldn’t switch them on.

“Jenson had been driving beautifully, but he has a very smooth, economical style and that made him a bit more critical to tyre temperature than Rubens was, which didn’t help. But I think the pressure of what had come to be regarded as a slam-dunk world championship had an effect. Perhaps sub-consciously he began to drive a little more conservatively. When you start coming up against pressure, all sorts of thoughts enter your head – not just for Jenson, but for me and the rest of the team. I think we all got a little bit anxious – I was probably one of the only ones who had been in a world title fight before, not that it made me any more capable of dealing with the situation – so we probably didn’t function as well as we could have done, but Jenson recovered magnificently.”

“I’ll always remember Jenson coming to me that morning and saying, ‘Don’t worry, I’m going to do it this afternoon.’

The final denouement came in Brazil – the penultimate race of the season – where Button scythed through from 14th to fifth to push the title beyond the reach of remaining rivals Sebastian Vettel and Barrichello. Brawn says: “I’ll always remember Jenson coming to me that morning and saying, ‘Don’t worry, I’m going to do it this afternoon.’ I think he’d had a quiet night with his Dad beforehand and realised this might be his only title opportunity. He drove brilliantly that day, overtook when he could, didn’t do anything stupid, pushed hard when necessary – a perfect job. But you could see it in his demeanour – there was no hint of anxiety, he turned up with an attitude of ‘Right, we’re going to do this’ and it wasn’t just false bravado – he genuinely had a spring in his step. When he crossed the line I actually burst into tears, something that had never happened before.”

Coincidentally, the team had picked up sponsorship for the weekend from a local beer company, Itaipava.

“To celebrate,” Brawn says, “Itaipava hired a downtown São Paulo club that was fairly, erm, raw… We went there and had an all-nighter, one hell of a party. I was 55 at the time and more sensible than some of the others, so it was lovely to watch younger members of the team completely letting themselves go. My wife Jean was with me, which was nice, and we did participate a bit, but we spent much of the night as observers, watching this wonderful thing going on – drivers, mechanics, the whole team. It was a night I’ll never forget.<

“I’d been lucky to taste success with other teams in the sport, but nine months beforehand this would have been inconceivable, so circumstance made it particularly special.

“I felt very proud of what we had achieved, and I still do: we had a team that competed for one year and has a 100 per cent title-winning record… It probably won’t happen again and our [note that he doesn’t say ‘my’] name is on those trophies.

“That can’t be taken away.”

Post-script

A month beyond Button’s title-clinching drive at Interlagos, Mercedes-Benz announced that it was to purchase Brawn GP… and Button signed a contract to switch to McLaren for the 2010 season to partner Lewis Hamilton.

“I went on holiday when the season was over,” Brawn says, “and Jenson phoned to tell me he’d decided to leave. We’d done a sensible deal for him with Mercedes and everything was looking pretty good, so who knows what might have happened if he’d stayed? It was disappointing after all we’d been through, but we got over it and we’re still good friends.

“The Mercedes thing was good and bad. It was obviously great for the team’s future, but with all the necessary bureaucracy it took forever to get the deal done and that caused us to miss the boat for 2010, because we didn’t have the funds we needed. It wasn’t until 2012 that the team got back on top of things .”

He remained part of the set-up until the end of 2013, when Lewis Hamilton marked his departure with the tweet, “Ross has been a great leader and teacher for me. He has built the foundations for us to succeed in 2014!”

Quite prescient, that.

The three Brawn GP cars survive, but only one is a runner

Just three Brawn GP 001 cars were built and only one of those, chassis 02, is in driveable condition. The team’s tiny budget meant few spare parts were made and many of these were scrapped after the Mercedes takeover.

Chassis BGP 001 01 Raced by Barrichello in the first 13 GPs until he crashed in qualifying for Singapore. Two wins, two fastest laps. Later rebuilt, now owned by Jenson Button, minus engine, gearbox and other parts.

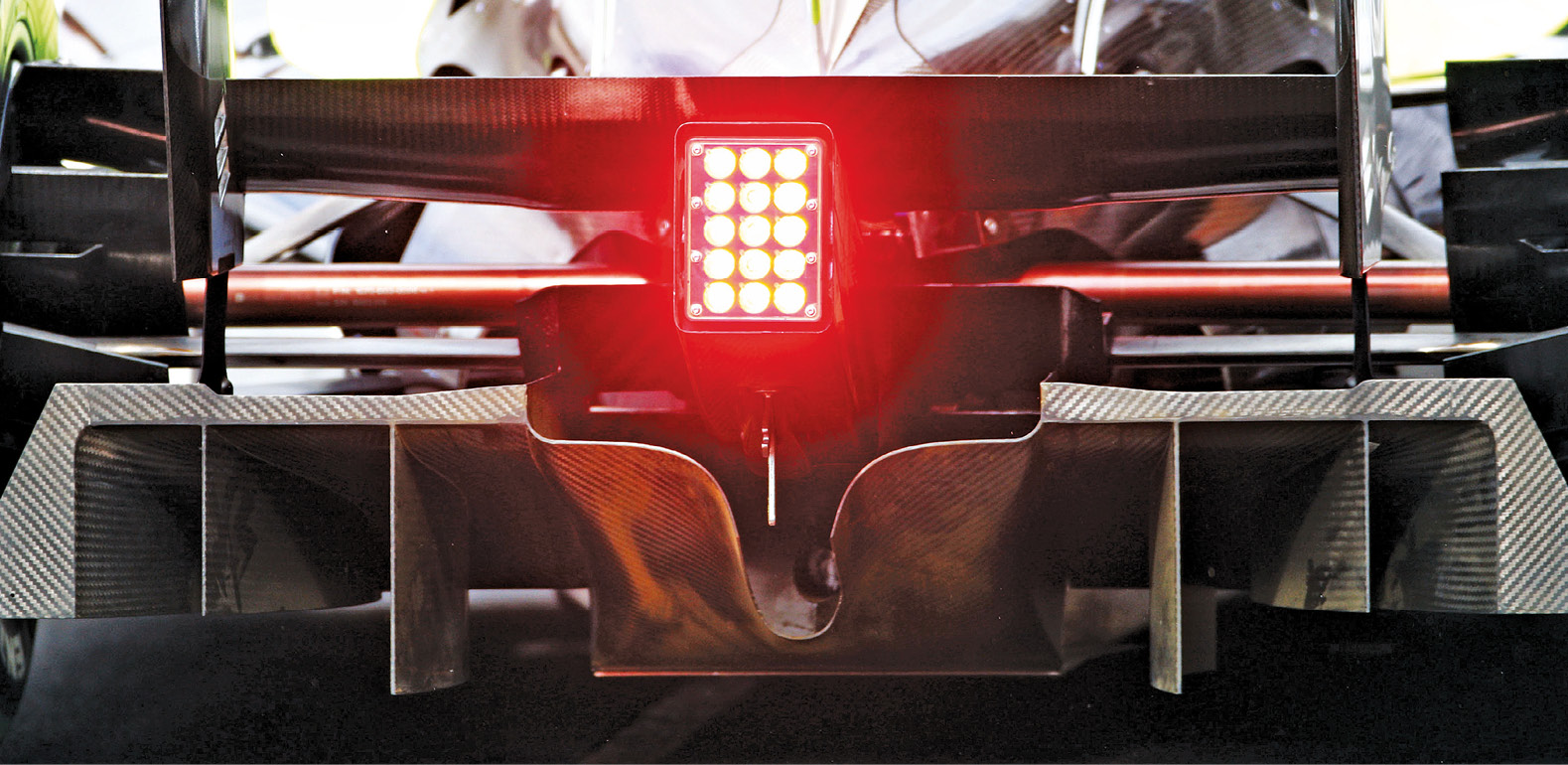

Chassis BGP 001 02 Button’s car for every practice and race – the title winner with four poles and six victories. Used by Mercedes GP for two years as a demo car in silver livery, now owned by Ross Brawn. Returned to running state by D3 Racing Solutions. It’s the one photographed on these pages.

Chassis BGP 001 03 Used for Barrichello’s last four races. Pole in Brazil, fourth in Abu Dhabi. Now owned by Mercedes, but not running.

The 2009 season began contentiously, but Ross Brawn believes there was more to his team’s success than trick aero

The dawn of the 2009 season was scarred by protests, rivals arguing that Brawn, Toyota and Williams contravened the latest regulations with their diffuser designs. While most took the wording of the rules literally, with single-piece diffusers of uniform height and length, the other three capitalised on a loophole that appeared to allow the central section of the diffuser to stop short of the car’s flat floor, creating an opening that permitted air to flow above the diffuser and generate extra downforce.

The FIA eventually ruled that this was legal and other teams copied it, but Brawn would be the only one of the three originators to win during the season. The practice was outlawed for 2010.

“Everyone talked about the diffuser,” Brawn says, “but I believe our success was due to the way our whole car was integrated. With new rules the interpretation always needs clarifying. We were spotting potential loopholes and FIA technical director Charlie Whiting quite often said, ‘Interesting, nobody else has asked that’ – so we deduced that we must be ahead of the game. I think we came up with a nicely integrated car, with all the aero packages working well in harmony and the double diffuser was a nice add-on.

“The idea was devised by a Japanese engineer who was working on the aero programme. We used to give them various projects with which to play around and he came up with this interpretation that we didn’t grasp initially, until we explored it more fully. That became the focus of attention, but in some ways we were quite happy for that to be the case. We knew the benefit of our diffuser compared with a normal design, but the big thing was the car’s overall integration. I honestly think we would have won races with a conventional diffuser, because we had started working on the new rules very early and were higher up the learning curve than anyone else.”