the fia

"The FIA, as well as learning how to measure barge boards, needs to differentiate between fighting for position and deliberate obstruction"

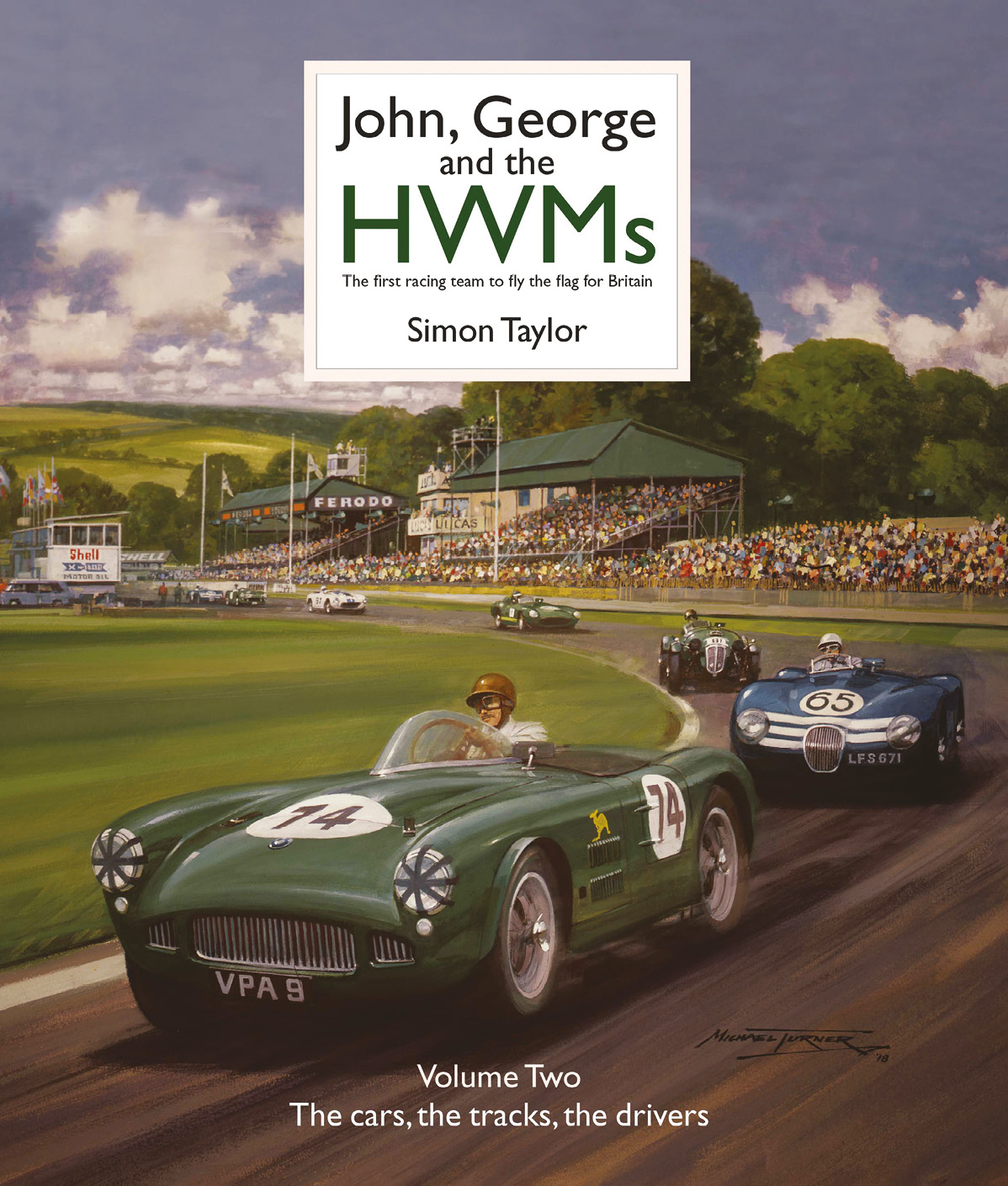

Simon Taylor, published by EVRO, £130,

ISBN 978 1 910505 32 8

Not an easy team name for ‘furriners’ to pronounce, yet when this unknown outfit with its chunky, purposeful-looking Formula 2 cars began snapping at the heels of the Continental works teams in the early 1950s it was suddenly a name to watch.

Of course, we know HWM didn’t become another Williams, or even an Aston Martin. From two West London garages, in Hersham and Walton, it blossomed into an amazingly active racing team and subsided once more to a successful (and continuing) car dealership – at least avoiding the fate of Connaught and Alta who simply withered. Those are the bookends of Simon Taylor’s work describing how engineer John Heath and racing driver George Abecassis formed a business and a racing team and ended up building their own cars, until Heath’s death on the Mille Miglia in 1956 put paid to a brave competition effort.

One volume of this classily boxed pair covers that story, a second the cars, tracks and drivers, and Taylor diverts on the way into ‘chapterettes’ on people, things and places such as fiery mechanic Alf Francis, the HWM badge (based on John Heath’s family arms) and the importance of hill-climbing – something dear to Simon’s heart.

But first, the sub-title: “The first racing team to fly the flag for Britain”. I tackled Simon over that, and he referred me to his Introduction, which says “Other cars had worn the green with distinction down the years, not least Napier, Sunbeam, Bentley and ERA…”, but that HWM’s “exhausting programme of three or four cars at two dozen or more events a year represented a comprehensive programme that had never been attempted before”. Which is a fair defence. Tiny as it was, HWM would race wherever there was start money, its offset cars doubling as sports or F2 entries, and often mixing it with grand prix machinery. While BRM floundered, HWM was showing that handling and grit made up for power and cash, paving the way for British glory to come.

Simon came to the subject in a romantic way: as a schoolboy he was gripped by a picture of the ‘Stovebolt Special’ (an HWM sports car packing a Chevy V8, in case you’ve never heard it tackling Prescott), dreamed about it long after and 43 years later bought it. He’s competed with it ever since. The burgeoning HWM files he assembled from that point were the basis for the book, and he has clearly burrowed into every written record and tackled everyone relevant he can find, using personal letters and photos to flavour the history with reminiscences both amusing and tough.

“It was a tight-knit operation on a borderline budget which gave Moss his first works drive”

Many photos of the team in the workshop, loading trucks or pausing at customs posts give you a rich taste of what it was like to grind over mountain passes in a 30mph converted bus with feeble brakes, one person trying to sleep in a hammock while one drove, with bribes of booze and dirty pictures to smooth border crossings and the constant risk of getting lost. One mechanic dropped off the back of the convoy and was found in tears unable even to recall which circuit they were heading for. Another was discovered shivering and snow-covered hours after the race car he was steering broke loose from the truck towing it, and nobody noticed. Yet they were so keen they put up with all this even though Heath told them he could only afford fish and chips and Woodbines as overtime pay.

Does that make them sound a shambles? They weren’t. That was the normal life of a race team then, and this was a tight-knit operation on a borderline budget which nevertheless gave a young Stirling Moss his first works drive. Moss raced an HWM more than 40 times and in his Foreword points out that for a while HWM was the most successful British single-seater team of all. In Formula 2 the Alta-engined cars were fast if not always reliable – the eternal story when money is tight – and attracted such drivers as Peter Collins, Lance Macklin and Duncan Hamilton, and if the 1954 essay into F1 failed, the later Jaguar-engined sports cars held their heads high, especially the two which raced as HWM 1 (the first of which contested the Mille Miglia with Motor Sport’s DSJ as navigator).

All that is mere results; more interesting is hearing what it was like to work for, or to run, a little team. How draughtsman/engineer Eugene Dunn discovered the team designing its chassis with chalk on the shop floor, or that they called Heath ‘The Baron’ while the mechanics were ‘the ‘Orribles’. Yet that was jest; the boss would muck in when needed. Languid and always dapper, Abecassis, of course, had a racing career outside HWM and Taylor weaves that into his tale along with the 1950s racing scene. Heath also raced but knew he wasn’t in the same class, so it’s sobering to learn that he had “a funny feeling” about that fateful Mille Miglia, reluctantly going ahead just because everything was arranged. More painful is a picture of the hasty will he scribbled the night before “in view of the hazards of motor racing”.

A year or so after that crash the team’s racing dried up and HWM reverted to dealing in competition and road cars of all sorts. It still exists in the same place, now the world’s oldest Aston Martin dealer.

A mere 19 cars emerged from the HWM works and Vol 2 lists their stories, along with HM Altas, Healeys and Facel Vegas and a coupé that might have sired some road cars – plus a section headed Of Arguable Ancestry – before detailing tracks where they raced (nice maps and posters) and adding profiles of HWM drivers. Amusingly this volume starts with a warning “Beware chassis numbers!”. Packed with quality illustrations, both sections feature Michael Turner paintings on their covers. But it’s those insider stories, entertainingly relayed, that make this so much more than just a history.

This title is available on the Motor Sport Shop