Breakfast With... Scott Pruett

Serial sports car champion, IndyCar star and a NASCAR podium finisher, one of America's most versatile drivers has called time on his career... to focus on producing wine

Lyndon McNeil

For four decades he has been as much a part of America’s sporting fabric as The Super Bowl, The Kentucky Derby and popcorn – less celebrated, perhaps, but an equally constant presence. And a successful one, too. To put Scott Pruett’s career in context, he began racing when Graham Hill was en route to his second Formula 1 world title, notched up his first significant championship success before Sebastian Vettel was born and has raced against pretty much everybody from AJ Foyt to Fernando Alonso via Dale Earnhardt and countless Unsers and Andrettis.

Headline accomplishments include 11 major sports car titles in his homeland, plus five outright victories in the Daytona 24 Hours and a class win on his only appearance at Le Mans. Beyond that, he has been a Champ Car race winner, a NASCAR front-runner and has also tried his hand at Australia’s V8 Supercar series. And the first time he drove a single-seater? That would be in an official Formula 1 test at Estoril, more than 30 years ago.

To paint a fuller picture, the 58-year-old agrees to meet for breakfast at Goodwood, where he is fresh from Lexus ambassadorial duties at the Festival of Speed. The original plan had been to hook up at the estate hotel, but that was forecast to be a touch hectic in the hillclimb’s immediate slipstream. The agreeable alternative is to use the charming café within the old control tower on the Goodwood Motor Circuit’s perimeter, where Pruett orders a sausage-and-egg sandwich (“I’ve never tried one of those before”) and the rather more familiar accompaniment of black coffee.

Given his competitive roots, it’s appropriate that a track day for Ford Mustang owners commences just as we sit down.

“It’s so long ago that I honestly can’t recall whether it was his idea or ours,” he says, “but my dad got my brother and I involved in karting when I was eight years old. I grew up on a farm and remember there being a yellow kart on the premises, although the only thing that really sticks in the mind is the chain continually falling off. I did my first race in northern California in 1968. It started with local events, then regional, then at a state level and I went on to take my first national title when I was 13.

The successful Ganassi-Riley BMW of Pruett, Montoya, Rojas and Kimball at Daytona in 2013 – Scott’s record equalling fifth Rolex 24 win

Motorsport Images

“I just kept going and going: I come from a very traditional, middle-class family, without much extra money, so it was based on graft. My dad was great. He said, ‘I’m not going to force you to race, but if you want to do it I’ll try to help.’ We did all our own work and, to ease the financial burden, started up a kart racing business, building motors and so on – my dad worked in aerospace and his firm’s claim to fame was manufacturing re-entry engines for the Space Shuttle. There was no obvious career path for me so I carried on karting and kept winning, eventually doing so at a professional level. I took part in the 1981 world championship in Parma, against Ayrton Senna – among others.

“I never imagined I’d be able to do the Daytona 500 or the Indy 500. As a kid it was never even a thought – it all seemed just too far away, so I just kept my head down and focused on karting and the next small steps that lay ahead. One of the guys that really inspired me, as a youngster at a racetrack, was Dan Gurney. He took the time to sign an autograph and chat to me for a bit – he was an absolute superstar, but made time for everyone. And he wasn’t just a great IndyCar guy – he was a great everything guy. I always hoped I might emulate just a tiny bit of what he achieved.”

SO, WHEN DID the thought occur that, actually, he might be able to carve a living from racing?

“Things were quite different back then,” he says, “because to find drives you had to make phone calls or write. I started sending letters to car companies and teams and was very fortunate to receive some help from Mike Kranefuss, at Ford Motorsport. I was by now into my early 20s, still winning in karts, and got my first opportunity to drive a racing car in 1983, with Mike’s help. I tested an IMSA GTP Mustang at Elkhart Lake and everything went well. That started the ball rolling – it seemed a little late to be making the change, but all the time I kept talking to people, to see what might be available, and in 1984 I got a call from a team asking me to share its GTU Mazda RX-7 with a gentleman driver. It was usually a midfield to back-of-the-pack car, but we ran in the top 10 and that attracted a bit of attention.

“I did a few more events with the team, including Daytona in ’85, but carried on karting to stay sharp. Mike Kranefuss called again later that year, because Ford wanted me to share a GTO Mustang with Bruce Jenner at Elkhart Lake. We led for quite a while, finished third in class and that really gave me some momentum. I was then invited to share Brooks Racing’s Thunderbird with Darin Brassfield in a Camel GT race at Pocono – and we won…”

The upshot was the offer of a full-time contract with Jack Roush Racing and Ford, a springboard to three major championship successes in as many seasons – two in IMSA with a Mustang bracketing the SCCA Trans-Am title in a Merkur XR4 Ti. “I have some great memories of that period,” he says. “In ’86 I drove at Charlotte one Saturday, finishing third with Bruce, then Jack flew me to Riverside, where I picked up my SCCA licence on race morning, started at the back of the grid and came through to win. I loved Riverside and wish the circuit still existed. We had so much success in a relatively short period of time and I was always wondering about the next step. How could I get into IndyCar? Could I make it to Formula 1?”

Late in 1987, his Ford connections helped him to get a taste for the latter.

After making his single-seater debut in 1988, Pruett did a full 89 season in a Truesports Lola-Judd, and took two podium finishes

Motorsport Images

“I was invited to test Larrousse’s Lola-Cosworth, at Estoril. I won in Trans-Am at Mosport Park on the Sunday, then flew to Portugal for a couple of days. It went pretty well – I was about 1.5sec off regular driver Philippe Alliot, which I didn’t think was too bad as I’d never previously driven any kind of open-wheeler, let alone an F1 car. Bernie Ecclestone was very supportive – and keen that an American should race in F1 – but I didn’t see how I would be able to make that jump and so started looking more closely at IndyCar.

“I was talking to team owners and they’d say, ‘Well, you’re doing great in sports cars but we’ve never seen you in an open-wheeler.’ So I had to take a gamble. I figured the best way to show what I could do was to get myself in an Indycar – and the only way to do that was to hire one. So I took all the cash I had, borrowed from friends or anybody else that would lend me money, rented Dick Simon’s Lola for the 1988 Long Beach GP and was running in the top 10 when the engine failed. During the summer I received a call from Machinists Union Racing, after regular driver Kevin Cogan broke his arm in Toronto. They wanted to know if I could fill in for a couple of races. I did Meadowlands and Mid-Ohio and gave a good account of myself, so suddenly people were paying attention. Jack Roush was pushing me to go with him to NASCAR in 1989, but I’d decided I definitely wanted to race open-wheelers.”

Towards the year’s end, an approach from Truesports boss Steve Horne culminated in a three-year contract and a promising rookie campaign. Pruett led in Detroit before finishing second, took another podium at Meadowlands, was co-Rookie of the Year (shared with Bernard Jourdain) in the Indy 500 (where he finished 10th, which ironically would remain his best result in the event), made his first oval start at Phoenix and took eighth in the final standings. The foundations for a strong 1990 appeared to be in place.

“My back was sore, but I didn’t realise it was broken. I remember seeing my left ankle swing through 90 degrees. It was almost as though my foot had fallen off”

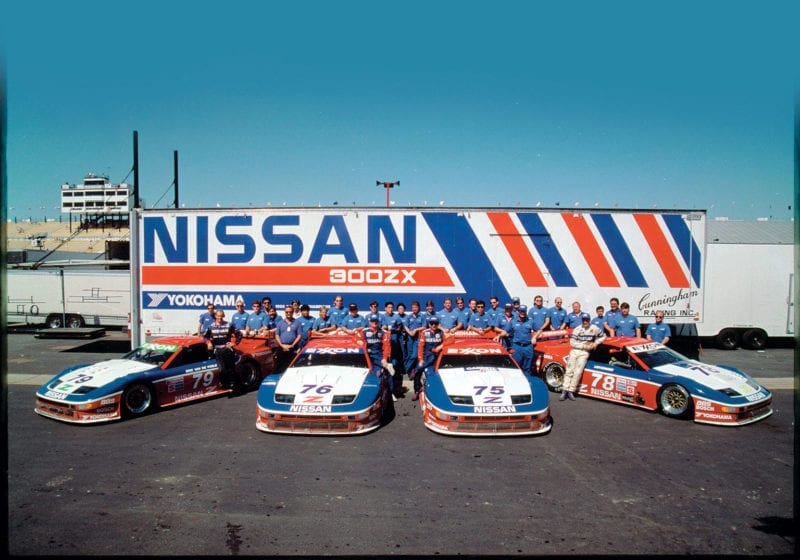

Pruett scored the first of his five Daytona victories in a Nissan 300ZX, shared with Steve Millen, Butch Leitzinger and Paul Gentilozzi

Motorsport Images

“I was really looking forward to it,” he says, “but we did a pre-season test at West Palm Beach and unfortunately one of the bleed screws on the rear brakes hadn’t fully been tightened. It was a simulated street track, with very little run-off. As fluid leaked out, the balance bar swung and I had a little bit of front braking but nothing at the rear as I was trying to turn onto the back straight. I hit some cement barriers head on – they estimated the impact speed at 100-110mph – and everything was just crushed. I recall sitting there, looking at the car, my legs and everything being a crumpled-up mess. My back was sore, but I didn’t realise it was broken. I took my helmet off and threw it up and over the cement wall, because I didn’t want it bouncing back and hitting me.

“Even though they had really good safety equipment at the track, they weren’t used to dealing with carbon fibre and it took 90 minutes to cut me out. They didn’t give me any pain relief, so the whole thing was excruciating. I knew my legs were a horrific mess and one of the last things I remember, as they finally got me out, was seeing my left ankle swing through 90 degrees as they loaded me into the helicopter. It was almost as though my foot had fallen off. On Saturday they put my back together, about eight hours of surgery, then on the Sunday they did the best they could with my legs and knees, which took another seven hours. It was two days before my 30th birthday and I celebrated the occasion in a hospital bed, just happy to be alive.”

Did he fear at any point that this might signal a premature end to his racing career?

“Some of the doctors thought so,” he says, “but for me it was a defining moment because it made me realise how badly I wanted to be racing – and I was determined to do whatever it took to get back on track. That was my sole motivation – I didn’t care about anything else. I treated my recovery as a job. I spent a couple of weeks in a bed, three months in a wheelchair and then progressed to crutches with a back brace. As soon as I could, I’d show up at 8.30, do all the physical therapy stuff until noon, then I’d take a lunch break and train again afterwards, because the parts of my body that worked had to be kept in shape for whenever I got back behind the wheel.”

That would be in October, seven months beyond the accident.

“I was still wearing back and leg braces when I arranged to test a Trans-Am car. I didn’t have medical clearance, but needed to do it for my own psyche. I’d been working so hard and had to find out how it would feel, to know that I could still do it, that I wouldn’t be scared of something happening again. I got back in and loved it, got that shot of adrenaline I needed. When [noted US racing doctor] Terry Trammell found out, he was on the phone yelling at me. He cussed me up one side and down the other, but I think that was mainly protocol. He was the one who regularly put all the IndyCar guys back together, so he knew the situation and understood the way drivers think.”

By January he was racing again, sharing a TWR Jaguar XJR-12 with Davy Jones, Raul Boesel and Derek Warwick in the Daytona 24 Hours and winning the following month’s IROC season-opener, curtain-raiser to the Daytona 500. Time, then, to return to CART.

In Patrick Racing’s Lola-Cosworth, Pruett challenged for victory at Indy in 1995 before retiring. He went on to win the Michigan 500 later in the year

Motorsport Images

“For 1991 Steve Horne had built his own all-American car, the Truesports – the chassis was fantastic, but our Judd engine didn’t perform so well against the Chevrolets. We had a pretty solid season and at the end of it Chip Ganassi made me an offer to race for him, but it was contract extension time and out of loyalty I decided to stay with Truesports. The team secured a supply of Chevy V8s for ’92, but this time the chassis wasn’t so good. Bobby Rahal had a go to see whether he could help, but he came away saying the car was terrible. Steve left during the summer and at the end of the season the operation folded, so I was sitting there, one year into a three-year deal with a team that no longer existed. That was a pretty tough awakening.”

Did he harbour any thoughts of trying his luck in Europe at that stage?

“Not really. You have to keep your finger on the pulse of all the things that are going on – who’s coming, who’s going, which drivers might be out – and doing that in just one series was a full-time job. I was looking around for rides, picking up bits and pieces but nothing really solid. I did, though, have a very strong relationship with Bridgestone from my karting days – I’d been a factory driver for several years – and they invited me to try a Formula 3000 car that they’d brought over to Riverside.

Pruett at Laguna Seca in 1999, when he switched to Arciero-Wells to focus on developing Toyota’s Indy engine. He took pole at Fontana

Motorsport Images

“Bridgestone had acquired Firestone in 1988 and I was still really close to many of the guys. It turned out that they were bringing the Firestone brand back to IndyCar and would like me to be the test driver, with Patrick Racing. That all came together at the end of 1993 – and at the same time I got a call from Chevrolet, asking me if I’d represent them in the Trans-Am championship, and then Nissan wondered whether I might be free to do the Rolex 24 at Daytona. The Nissan was on Yokohamas, I was testing IndyCar Firestones and the Camaro was on Goodyears – it was all a bit crazy, but I scored my first outright Daytona victory with Nissan [with Butch Leitzinger, Steve Millen and Paul Gentilozzi], took the Trans-Am title and covered about 15,000 test miles with Firestone.

“Rolling into 1995, I maintained my relationship with Patrick, scored my first IndyCar win in the Michigan 500 and was very disappointed not to win Indy. Scott Goodyear and I were back and forth between first and second. In the briefing they’d said you weren’t allowed to pass the safety car before the green flag. I was leading with 18 laps to go, somewhat jumped the restart and came around Turn Four to find the safety car going slowly – so I got off the throttle and Goodyear, who had a full head of steam, came past. He was a little faster than me, but my car was better in traffic, so I was confident I’d get by once we caught some slower cars. What I didn’t know was that Raul Boesel had blown his engine and dropped a little oil at Turn Two. I slid up the racetrack and just touched the wall, enough to break the wheel. I slid back down and caught the fence on the inside. Scott then got the black flag for jumping the restart and Villeneuve came through to win [having at one point been two laps down]. It was a crazy day at which I’ve always looked back and thought, ‘Damn, that one got away.’ The Indy 500 had slipped through my fingers.

“Perhaps that conditioned my thinking at Michigan later in the year. Al Unser Jr and I were involved in a straight fight. Coming towards the last lap I knew he was probably going to slipstream past me, which he did, so I decided to try a dummy to the inside and then head straight back to the high line and stick to my guns: it was going to be chequers or wreckers, I didn’t care. I was so close to that elusive first victory… if I crashed, so be it. He tried to cover as I went to the inside, so I went back to the top of the raceway, we ran side by side through Turns Three and Four and I won by inches.”

Or 0.056sec, according to CART’s official timing.

Switching to NASCAR in 2000, Pruett predicted it would take three seasons to mount a challenge. He was then dropped after just one…

Motorsport Images

“I honestly believe I could have fought for the IndyCar title in 1995, ’96 and ’97,” he says, “but I was hammered by engine failures.”

He added another win to his CV, at Surfers Paradise in 1997, and the following year had what would on paper be his best season to date: there were no victories, but three podiums and consistent strong finishes helped him to sixth in the standings during what would be his final season with Patrick.

“At the end of the year I received a call from Cal Wells, asking if I’d like to join his IndyCar team for ’99 to assist with Toyota’s engine development programme. It was tough, with a number of failures, but we all know that big manufacturers eventually get these things right. We qualified third in Australia and ran strongly, then took pole at Fontana [average speed 235.398mph] – a first in the series for Toyota.

“I’d by now done 10 years in IndyCar and I’m one of those guys who likes driving anything, so when Cal looked at getting involved in NASCAR for 2000 I thought, ‘Why not have a look?’ The Toyota thing was off and rolling and looked like it was going to be good, and Cal was happy for me to switch, but before I committed I said, ‘Look, everybody has to realise that we have a brand-new team and driver in NASCAR terms, so our first year is going to be really tough, in the second we’ll be finding our way and in the third we’ll be ready to challenge for wins. It was a case of, ‘Yeah, yeah – we understand.’

“I think we had a pretty good season, given that everything was so fresh, and I had my most memorable race at The Brickyard, swapping places constantly with Dale Earnhardt Sr as we scrapped for about ninth. At the end he came up to me and said, ‘Hey Pruett, I think you’re finally getting this shit figured out.’ That’s a cool memory.

Celebrating with Max Papis in 2004 after clinching what would be the first of four Grand-Am titles

Motorsport Images

“Unfortunately, our sponsor Tide’s management regime changed and at the end of the season they went to Cal and said, ‘We’ll extend the contract by three more years, but we want you to get rid of Pruett and put Ricky Craven in the car.’ So that’s what happened. I was pissed off at the time and decided I’d had enough with racing, so I went to work for ESPN and Speed, as an analyst at all the Champ Car races. Then I received a call from Corvette. ‘Hey, d’you want to come and do Le Mans?’ They needed an extra driver for the longer races, so I went to Le Mans in 2001 and shared a class win.”

“I still have the contract Chip Ganassi offered me in 1991 – the one I didn’t sign – and I wasn’t going to make that mistake again”

He consequently has a 100 per cent strike rate at La Sarthe, so why hasn’t he been back?

“I talked about it,” he says, “but I wanted to have a chance to win outright – and I wasn’t close to any of the manufacturers who were in a position to challenge at that time. Later in 2001 Chip Ganassi called and invited me to do a couple of NASCAR rounds. I started filling in for him on some of the road courses [he finished second at Watkins Glen in 2003, third at Sonoma in 2004] and that helped me start rebuilding my relationship with Chip. I still have the contract he offered me in 1991 – the one I didn’t sign – and I wasn’t going to make that mistake again.

“In 2002 I was still doing some broadcast work and driving occasional races for Chip, but I was really beginning to miss being behind the wheel – and being in the paddock environment made it that much worse. I knew I had to get back in a car and had the good fortune to be called by Rocketsports, to see if I wanted to drive its Jaguar XKR in Trans-Am. We won about eight races in 2003 and took the title, then Chip called and offered me a full season in Grand-Am with Lexus… and we went on to crush the record books for the next dozen years. Race wins, titles, victories in the Daytona 24 Hours and at Sebring – it was just an incredible run.”

On his only Le Mans appearance, Pruett shared the class-winning Corvette

Motorsport Images

He was champion with Max Papis in 2004, then Memo Rojas in 2008, 2010, 2011 and 2012 and added four more victories in Daytona’s endurance showpiece to draw level with Hurley Haywood as the most successful driver in the event’s history. Is there a secret to Daytona success?

“The trick is never to put yourself in a bad position when passing – don’t go to the outside unless you know exactly who is in the other car – wait a moment until you can pass on the inside. You come up against buy-a-ride doctors, lawyers and one-off racers. In the middle of the night some of them have no clue where they’re doing, but if you get hit – no matter what – then it’s your fault.

“When I started out in the 1980s teams sometimes won Daytona by 10 laps, but in the modern era the cars are so robust that you can drive the crap out of them for 24 hours and you’re sometimes winning by seconds rather than laps. You can’t afford to have any delays at any time, because that will eliminate you from contention. They start 70-odd cars on a 3.3-mile track, it’s really, really hectic and the craziest time is between about two and four in the morning, especially if it starts raining. You can’t see much, the track’s slippery, it’s not easy for professionals to settle into a rhythm and then you get the variable driving standards…”

As Ganassi switched from Lexus to BMW and Ford – part of the latter programme involving development of the twin-turbo V6 that would subsequently be dropped into the company’s GT racer – Pruett remained on board before opting to rejoin Lexus to work on its RC F GT3. “It was a pretty tough decision for me to leave Ford, with whom I’ve had such a long relationship,” he says, “but I really love the Lexus culture. It was supposed to happen in 2016, but things tripped up slightly and we ran the car only in some tests at Fuji, before doing a full season in 2017. I’d been around long enough to know the first year would be tough, but you’ve just got to bite the bullet and get on with it. We learned so much and it has been great to see the car in Victory Lane this season, not just in the US but also in the Blancpain series in Europe. It feels good to have been a part of that foundation.”

Having previously taken a class win in the Sebring 12 Hours, Pruett added an overall win in 2014, sharing with Memo Rojas and Marino Franchitti

Motorsport Images

But he is presently watching the car only from the sidelines, having opted to call time on his career after the 2018 Daytona 24 Hours, which yielded a 29th overall and ninth in class.

Why was this year the right time to stop?

“I think every driver gets to a point where they start looking at a race from the chequered flag backwards, not from the green flag forwards – and I’d reached that. I was also able to retire on my own terms rather than anybody having to help me out through the door. I want to get on with my next chapter. I loved everything about racing and what it offered me, but my wife and I have written four children’s books, I have my Pruett Vineyard and am kept busy as an ambassador for Lexus and Rolex… You reach a stage where the reality of life, the reality of getting older, hits home. I’m in the gym, training my ass off, and my body doesn’t respond as it did when I was younger. My son is 18 and just has to look at a set of weights to get bigger!

“I just began to realise how thankful I was for all the great times the sport has given me, all the memories. When I look at the guys I raced with or against – Klaus Ludwig, Hans Stuck, Bob Wollek and Derek Bell from sports car racing in the 1980s, Mario and Michael Andretti, Al Unser Sr and Jr, Rick Mears in IndyCar… the list is endless. When you look at all the rivals I’ve encountered across my career, it’s a Triple A list. People ask for my best memory, my best race, my best championship, but there are so many that it’s impossible to choose. How can you compare giving Corvette its first Le Mans class win with going wheel-to-wheel with Al Jr at Michigan? I’ve been incredibly lucky – and even shared the track with Fernando Alonso in my final race.”

Pruett spent 2017 developing and racing Lexus’s RCF GT3. He retired after driving the car at Daytona this year

Motorsport Images

Can he explain the secret of his longevity?

“I wish I knew,” he says. “All I can say is that I passionately love the sport. I’ve always made sure I was properly prepared – I never want to look back and say, ‘I should have been smarter, I should have trained harder.’ It’s too easy not to. I was always one of the first to arrive at the track in the morning and one of the last to leave. I’d chat to my guys, study the data and everything – but it was natural. I loved the sport, so it didn’t seem like work – and when things are like that you can’t get enough of it. I’ve loved every moment, but reached my decision because I wanted to spend time on other stuff, like my winery and my family. When I was racing I always used to repeat a message when I was interviewed, ‘Hi to my family at home.’ My two younger ones thought I was inside the TV…”

Are there any circuits on which he wishes he’d been able to compete?

“Probably only Monaco,” he says.

Has he settled into any kind of daily schedule, post-racing? “Not yet,” he adds. “Ever since Daytona I’ve been trying to find my new ‘normal’. I spoke to Danny Sullivan about this and he told me it took him about two years to re-establish any kind of routine after he’d quit racing. But I’ve got plenty to keep me occupied.

“I think my interest in wine probably comes from my upbringing, growing up on a ranch. I love the outdoors, but the whole thing has been an unexpected adventure – and something I wanted to do myself. I did all the soil study, all the climate study and obtained advice from some of the best people in Napa Valley, which is an incredible area for wine and not too far away. I didn’t get into this so I could say I had a vineyard – I only wanted to make wine if I could do so at the highest level, the same approach I took with my racing. I cleared the land, planned the plants and got it all established. I’ve been tempted to expand, but have decided I’d like to keep it as a small, intimate business.”

Does he have any particular recommendations?

“I’d like to hope that everything we make is good,” he says, “but for racers the Championship Cuvée Syrah is pretty cool.”

And is that absolutely, definitively it for racing, after 50 years behind the wheel? He wrinkles his nose, and smiles, “Perhaps Daytona,” he says. “I love that place. I know I’ve retired, but if I had the right opportunity to drive a potentially winning prototype, I’d have to think about it. Maybe number six is out there for me…”