Lunch with... Gordon Spice

He was sacked from a £10-per-week job – by his own father – and never saw the point of gyms, but that didn’t prevent him standing on the podium at Le Mans

For a driver who claims motor racing was only ever second to his commercial activities, Gordon Spice’s track record is striking. He never won Le Mans, but twice finished third and notched up a few class victories. He never won the British Saloon Car Championship outright, but took several class titles. He was thrice crowned in the Group C2 division of the World Sports Car Championship, cars bearing his name conquered many an endurance race on both sides of the Atlantic and he won the last major event on the original Spa road circuit, complete with Masta Kink. He also thought it a good idea to graduate directly from Minis to Formula 5000: it wasn’t, though he did eventually score a race win.

To explain his rationale, he invites us to meet him at La Cloche, a French restaurant within The Carpenters Arms, a traditional country pub in Sunninghill, Berkshire. Now a trim 76, Spice starts with Serrano ham and melon before moving on to steak frites, washing them down with a single Virgin Mary and a few glasses of still water.

By his own admission, Spice had a privileged upbringing. On their respective 21st birthdays, he and older brother Derek were given cars. “It had to be black,” he said, “and I could choose between an Austin A40 and a Mini. Derek already had an A40 and had started souping it up while on national service in Holland. When he returned he fitted a Downton F3 engine and began racing it at Goodwood. One day he asked if I’d like to have a go during a test session and I thought it was terrific fun, so I decided to try racing.”

Gordon’s A40 was soon written off, when rear-ended on the Chiswick flyover, and he used the insurance settlement to buy an MG TF. “That was an absolute disaster,” he says. “I entered four races in 1962, qualified for only two and didn’t finish either, so I got no signatures on my licence.

“I was working for my father at the time as a chocolate salesman. My feeling was that I shouldn’t have to use my birthday present as a company car and that he should buy me something better for business use, which he did. That year he paid me £10 a week and sixpence a mile, so the fuel allowance was more profitable than the salary. I used to jack the car up and wind the odometer forwards to claim more miles, and thus more money for racing, but Dad caught me at it one morning, so quite rightly fired me. That forced me to find another way to make a living and I ended up selling encyclopaedias. In the space of three months I’d accumulated about £5000 – a huge amount at the time, especially for somebody who had been on a tenner a week. I sold quite a few, they weren’t cheap and the commission was good.

Driving a 1-litre Mini for the Arden team, Spice was a class-winning seventh in the 1968 British Saloon Car Championship

Motorsport Images

“That gave me enough to buy a Morgan Plus Four and go racing, but I soon realised I knew bugger all about it so went to work for Morgan specialist Chris Lawrence on a voluntary basis. I was allowed to prepare my car there and benefit from his expertise, because in those days you had to change a Morgan’s stub axle pretty much every time you went out. That was how I got into proper racing. For 1964 I put an SLR body on it, but wrote the car off first time out at Goodwood – I crashed at the chicane when the wall was still made of bricks. That was pretty much the end of my Morgan career, but I’d learned a lot.”

Lawrence was also involved in the Deep Sanderson Le Mans project, in which Spice got to make his Le Mans debut in 1964. “Hugh Braithwaite was the nominated lead driver and I was only a reserve,” he says, “but Hugh was fairly well established by then and after one practice lap he decided he wasn’t driving it, so I was in. Chris ran out of water during the first hour, and in those days you weren’t allowed to top up until you’d done a certain distance, so the car was disqualified.”

Spice had invested personally in the Deep Sanderson project, but promised money from elsewhere never materialised, Lawrence was badly injured in a road accident after the race and Spice returned to the UK to discover he needed to sort out various creditors. “That was all going very nicely until Chris reappeared one weekend and took away all the stock and equipment – he wasn’t my favourite person at that point and I called in the receiver.

“One of the creditors had been Downton Engineering, so I called [co-owner] Bunty Richmond, told her what had happened and explained that no more payments would be forthcoming as the company had been wound up. She asked whether I’d like a job – they offered me a role as sales manager, which is how I got into driving Minis. I was on a wage plus commission, but I really wanted to race so asked if they would lend me engines to use in my Mini at the weekend if I took a slightly lower salary. I hadn’t actually bought a Mini at that point, but knew Downton encouraged their employees to race, as a sort of test-bed – and that’s what happened. Throughout my Mini days I was very much aided by Daniel and Bunty Richmond because I had free engines – even after I left at the end of 1965 to start my own accessory business.

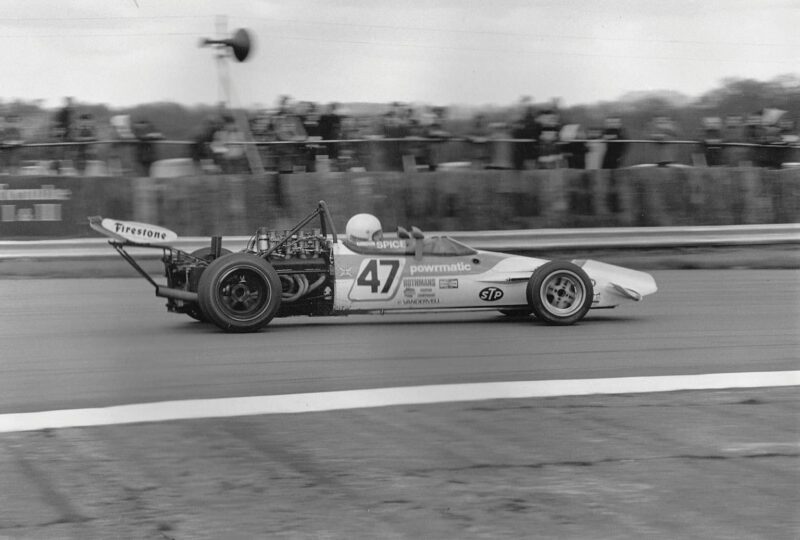

Steps up to F5000 in 1972. He raced the Kitchmac – a modified McLaren M10B

Motorsport Images

“I raced Minis for three seasons as a privateer in the British Saloon Car Championship. At Brands Hatch once, I think in ’66, I knew Jim Clark would lap me at some point in his Cortina. I’d never been in the same race as him before and he was a real hero of mine, so when I saw him coming up behind I left lots of room as I was turning in to Paddock. I was so busy watching his wheel-waving antics, so in awe, that I got on the marbles and whacked into the sleepers. That was the end of my season, all because I was watching Jim Clark.

“When I started to get better results, Daniel Richmond said to me, ‘Look, we can go on lending engines but you mustn’t beat the works cars’ – they were using Downton motors, too. I was very aware of that in the first race of 1967, supporting the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch, and the factory drivers had been having all sorts of trouble so I found myself in the lead. I waited for John Rhodes – made it quite obvious, actually – and let him through, but John Handley was nowhere to be seen so I finished second. I’d done my best, but you never know the repercussions so I went to see the main trade suppliers – we relied on people like Dunlop and Champion, who were the main supporters of saloon car racing back then. I pointed out that I had a car that could beat the works Minis, though I wasn’t supposed to, so asked if I could be paid the same bonus for finishing third as I would if I won. To my surprise they agreed – and as they had a healthy bonus scheme that was very profitable. That was how I could afford it – and it justified what I was doing because I’d always felt a bit guilty about racing as I was primarily a businessman, which remained the case throughout my career.

“When I launched my accessories company the timing was very lucky. In the 1960s, remember, cars were very sparsely equipped – they didn’t always have things like wing mirrors, aerials, interior mirrors or heaters… They were incredibly basic and my shop in Ashford exploited this. And because of my weekend activities I also got involved in selling racewear – the RAC MSA had brought in all sorts of rules after Peter Procter’s fiery accident at Goodwood in 1966. It became mandatory to wear properly protective clothing, so we began selling overalls, fire extinguishers, helmets and all that sort of stuff. We operated as a retailer for about a year, and then we went wholesale. It was a one-stop cash-and-carry – and for all the glamorous stuff such as crash helmets we also had anti-freeze and all the other crap that went with car accessory shops.

“It was also quite good to have someone with a bit of racing experience – me, basically – floating around the shop to chat to customers. They loved it. I could tell them that such and such was the best helmet with some credibility. Go and look for a car accessory shop today and all you can find is Halfords, which I consider to be rather expensive. Every town used to have an accessory shop or two, because people used to do DIY maintenance as they couldn’t afford garage prices. That’s all gone by the board with modern cars.”

Spice’s Lola T332 ahead of Richard Scott’s newer T400 at Snetterton, a couple of weeks before the test accident that ended his season

Motorsport Images

For 1968 he joined Jim Whitehouse’s Arden team to race a 1.0-litre Mini in the BSCC and ended the season as class champion, which earned him a chance to race a Britax-backed Downton-run works Cooper S the following season. “I suggested that Arden hire Alec Poole to replace me,” he says, “which they duly did… and he went on the take the title outright. I often remind him that he owes me for that.

“I had another decent year in ’69 – and a spin-off from that was that I got to meet José Juncadella, who had taken on the Cooper concession for Spain. I did quite a lot of the initial testing for them and he asked whether I’d like to share his ex-Paul Hawkins Ford GT40 in a few races.

“Driving it should have been a culture shock after a Mini, but I found it much easier – and far less physical. It just went where you pointed it, a wonderful feeling. There was quite a healthy sports car championship in Spain at the time and many of the locals had stars driving with them. I was very much a non-star, but Alex Soler-Roig had Jochen Rindt sharing with him and there was a lot of competition. I got plenty of seat time, too, because Juncadella was only really interested in doing the start and the finish – he thought the bits in between were boring, which was terrific for me because I was getting the practice I needed. He’d phone up out of the blue and say, ‘Are you free this weekend? Come over.’ He’d always send me a first-class ticket – I’m not sure he knew any other class existed.”

At this stage, aged 29, Spice’s career took an unforeseen diversion. “I’d decided that I really fancied making a go of racing – so in 1970 I tried to tackle the European F5000 Championship on my way to F1, although that plan didn’t quite work out. I drove the Kitchiner K3A and managed about half a season before running out of money. Our budget – which included buying both chassis and engine – was £1500. It was a clever little car, but very unreliable: with its short wheelbase it was a bit like driving a Mini, in that you could throw it sideways to slow it down. We got some results though, including a fourth at Monza. I was also racing an Arden Mini in the BSCC, on the understanding that F5000 took precedence, but by then I’d rather lost interest in Minis if I’m honest. I did it because I said I would.”

For 1971 he acquired a McLaren M10B that Howden Ganley had raced successfully the previous season. “They were offering good start money for the Argentine GP,” he says, “a non-championship race that admitted F5000 cars. I just had to finish both heats, because the prize money was so good, and I took Tony Kitchiner with me as my mechanic. Halfway through the second heat my neck went – I was never all that fit. The challenge was just to keep the car on the track, so it was a matter of survival. I came back loaded, which kept me going for that season.

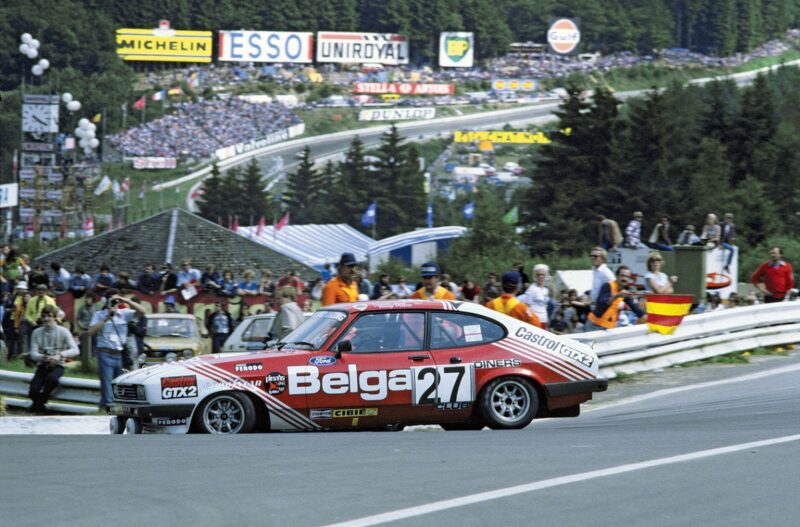

Spice teamed up with Peter Clark to take class victory and fifth overall in 1975 Spa 24 Hours

Motorsport Images

“I knew nothing about the mechanical side of racing, but Tony reckoned he could do a better car and for 1972 the modified M10B ended up as the Kitchmac. He was a lovely man and a total enthusiast, but I think he was working very much on gut feeling rather than science.” The car obtained some decent results – including a fourth at Mallory and a sixth at Silverstone – before he ran out of funds.

“I’d more or less given up on racing after my failed attempts at F5000,” Spice says, “but a chap working for me at the time – Ernie Ungar – had come from Ford in a bid to bring some discipline to our company. He introduced me to a friend of his, Stan Robinson, who owned Wisharts Garage in County Durham and wanted to go racing. He asked if I’d like to drive a Capri for him in production saloon racing and that was the start of my long Capri association.

“We did reasonably well that year and I suppose one of the highlights was finishing second to James Hunt’s Camaro on the Tour of Britain. I knew James well and thought he was a bit unsporting on that occasion, because we were quite close and the final stage was a hillclimb, which he ran on foot beforehand. I thought that was completely outside the spirit of the thing, because I couldn’t have walked it let alone run it. He consequently knew which way the corners went, and won.

“I enjoyed the Tour of Britain while it lasted – and it really highlighted the difference between racing and rally drivers. One year I was on a foggy forest stage and knew Ari Vatanen was starting behind me, so I thought I’d wait for him to come by and then track him – but he came flying past and within 10sec had vanished. That illustrated how much better the rally drivers were. I thought I might at least have been able to follow, but there was no way. I couldn’t see a bloody thing…”

Inspired by results, Robinson decided to step up to the BSCC for 1974… with a Plymouth Hemicuda. The car never worked properly, though, and Spice rarely appeared. And then he took a holiday in Portugal.

“While I was there I met a chap called Chris Reed, who would pop down to the local post office to wire some money to Hexagon Racing whenever they needed it. They were short of £10,000 to run John Watson in the Canadian Grand Prix. I asked how often he’d been doing this and he said he was able to afford it, at which point my ears pricked up. When I told him I was a failed F5000 driver, he asked whether I’d like to try my hand at F1. I didn’t think I was quite at that level, but I did say I’d like a proper crack at F5000. He was up for it, so we bought a second-hand Lola T332 – quite a good car, but I was still basically a businessman competing against serious drivers who were doing this on a full-time basis.”

Spice shared the Dome RL with Chris Craft, but a lack of tyre temperature meant it was a handful at Le Mans

Motorsport Images

There was a risk that round two at Oulton Park might be cancelled, following a heavy snowfall, but marshals and volunteers cleared the circuit and the race began in bright conditions on a track surrounded by banks of snow that had been melting awhile. “The organisers suggested we should try wets, but I went out on slicks because I didn’t think I had time to change tyres. There was absolutely no grip, though, so I came in to switch to wets while most of the others – who hadn’t felt comfortable on wets – did the opposite. Wets were the right call – I think Teddy Pilette was on them, too, and led initially. When he dropped out I found myself in the lead – that was my first major international victory.”

During the summer, however, his season – which he was dovetailing with a Capri drive in the BSCC – ended brutally.

“I was testing the Lola at Mallory and didn’t realise a front tyre was deflating. I went straight into the Esses sleepers at some speed. I think my knees ended up somewhere behind my neck, I lost my front teeth, needed skin grafts and was off work for three months.

“The first time I was allowed out of hospital on day release, I was in a wheelchair and, after visiting the office, a few colleagues took to me to a nearby pub. At the time the only thing I drank was Carlsberg Special Brew, but I was a bit out of practice as I hadn’t been able to drink for a few weeks. I had three or four, so was fairly pissed, but that gave me the courage to call the ward matron and tell her I was going to discharge myself the following day. I did just that and went to the Caribbean to recuperate. I’ve not touched another drop of Special Brew, but learned to drink rum while I was away and that has been my only tipple ever since – a direct consequence of my F5000 shunt.

“I also promised that I wouldn’t ever race an open car again. A few years later, when Dome asked me to share its Zero RL with Chris Craft, the cockpit originally had a small aperture at the top, but I agreed to drive so long as they put a flap over it so that I wouldn’t break my word.”

For 1976 he was back in the BSCC, driving a Wisharts Capri – the first of five straight seasons in which he would be class champion without ever taking the title outright. From the following year he would run under the Gordon Spice Racing banner, with his cars prepared by Peter Clark and Dave Cook at CC Racing Developments in Kirkbymoorside.

“They had been my mechanics in 1973,” Spice says, “and when I set up my own team I helped them start their new business. It was far cheaper basing the cars in North Yorkshire, with local labour rates, and transporting them a fair distance to race meetings, than it was having them located nearer the circuits.

Leading Vince Woodman, and Rouse and Win Percy at Mallory Park in the BSCC 1980

Motorsport Images

“I enjoyed the Capri era. Although I won the class championship several times, I didn’t mind not winning the title outright because I understood the logistics of the multi-tier class structure. We weren’t an official Ford works team, but probably the next best thing. We got a lot of publicity – not on a level the BTCC gets today, but enough to generate good custom for my business. It was never on TV back then, but the kind of people who bought car accessories, rally jackets and so on tended to be fans of saloon racing.”

There were also other diversions, such as racing a Charles Ivey Porsche 911 at Le Mans in 1978 (“My first proper drive there, I suppose. The works team could change a gearbox in 40 minutes with an army of mechanics – but Charles could do it single-handedly in 45. If he hadn’t had to do that we’d have won our class”) and the aforementioned Dome.

“Over the Le Mans weekend that was possibly the most dangerous car I’ve ever driven. It had been fine at Silverstone, but in France we just couldn’t generate any tyre temperature. For political reasons we had to run it on Japanese Dunlops that were like concrete. It was impossible to get any heat in them. It was very fast – I think we were second-quickest down the Mulsanne Straight – but very difficult to drive. Before the start, I said to [co-driver] Chris Craft, ‘There’s no way this thing is going to last 24 hours, so I think the first man in should park it.’ I won a coin toss, put him in to bat and wasn’t expecting to see the car after an hour or so – but he kept coming past. I started getting ready for a stint, thinking he might have ratted on the deal, but then one of the fuel pumps packed up and it stopped out on the track. I was so relieved. It was obviously a disaster for the team – I kept my helmet on for a bit so that they couldn’t see I was smiling…”

Spice heads for third place in the Rondeau M379 he shared with Francois Migault at Le Mans in 1981

Motorsport Images

He finished third overall at Le Mans with Rondeau in 1980 and ’81, the first of those also yielding a GTP class victory, but says the pick of his victories during this period came in the 1978 Spa 24 Hours – the final major race on the full, 14-kilometre track.

“That was particularly sweet,” he says, “because I’d been trying to win it for a few years. It was also quite lucky, because we’d been suffering punctures during practice – Goodyear flew in a more durable compound for the race, but I had a blowout near Blanchimont, which put me in the barriers and did a bit of damage, so we had to come from behind. Chris Craft had a blowout at Burnenville, too, and damaged his wrist, but for which I’d have kicked Teddy Pilette out of my car and put Chris in.

“Teddy was a really good single-seater driver, but perhaps not quite so quick in a Capri. It was politically good to have a Belgian in the car at Spa, but we were running in the colours of Belga cigarettes and I hadn’t realised he was contracted to Gitanes. I qualified on the front row and before the race Teddy said, ‘Gordon, I want to be paid for this.’ I pointed out that he’d agreed to do it because it was a bloody good car to be in. I didn’t want to fall out with him – and certainly didn’t want to have to find another driver at that point – so asked him if we could sort out a deal afterwards. During the race, however, he didn’t behave very well, wearing his Gitanes jacket while giving press interviews and so on. I was furious and when it came to the final stint – he was supposed to drive for the last hour – I wouldn’t let him in the car. I liked Teddy, but wasn’t sure I could trust him on this occasion. The pit marshals came across and tried to tell me I would exceed my permitted time in the car, which wasn’t true, but that was quickly sorted and off I went.”

The Capri era formally ended at the end of 1982, the final year that the BSCC ran to Group 1 regulations. “By the end of 1981 it was clear that Rover’s SD1 was now a better racing car,” Spice says, “so I went to see Ford, told them the Capri had had its day and that I felt my team could do a good job for them with its Group C sports car programme – the C100 project hadn’t been without its problems. We agreed a deal, but then Stuart Turner came in as motor sport boss and axed both Group C and the Ford RS1700T rally programme. I think we would have had a bloody good car – it was a Tony Southgate design, effectively a prototype of the Jaguar XJR-6 that he later produced for Tom Walkinshaw.

Spice has the distinction of winning a race on the full Spa circuit, sharing with Teddy Pilette in 1978

Motorsport Images

“Ford was very generous after pulling the plug, though. They paid my driver salary – more than I’d ever previously earned from racing – and all the equipment became ours. I asked whether I could buy their existing cars, but one went in the crusher and the other was converted into Transit Supervan 2, so that was the end of that.”

It would also be a trigger for the launch of Spice Engineering.

“I had all the kit you needed to run a team, courtesy of Ford, but no cars. Then Ray Bellm turned up, agreed to buy half the assets and we agreed to go 50/50 on a new company.

“In 1983 I shared a Tiga with Neil Crang in a couple of endurance races. It was very obvious to me that the car would never be competitive with a Chevy engine, which it had at first, so I suggested switching to a DFV and making a decent Group C2 car. That was the basis of the first Spice Tiga – we basically copied the front end of a Porsche 956, lightened the car and made it a bit shorter. We raced that in 1984 and 1985 (taking a class win at Le Mans) – and then the first true Spice appeared the following season.”

It was the dawn of a purple patch, Spice’s Group C2 cars proving popular – and successful – with customers in the World Sports Car Championship and IMSA’s North American equivalent. There were multiple class victories – and titles – in both series, with Spice himself sharing further Le Mans success in 1987 and ’88.

“I think sixth overall at Le Mans in 1987 stands out,” he says, “because that was pretty much unknown for a C2 car. We won the class a few times in that period, then in 1989 we went C1 – which theoretically should have suited the team, but didn’t because the Cosworth DFR engine proved unreliable. The C1 project – and the decision to can Group C2, which wiped out what had been a very nice niche market for us – effectively bust the company, because promised funds never materialised and sponsorship proved elusive. We should have stopped racing before we did. We probably had the technical ability to compete in C1, but we simply didn’t have the money to take on the likes of Toyota and Peugeot.”

Spice chassis raced on successfully into the 1990s, but the man himself retired after Le Mans 1989. “My accessory business was in deep trouble at that stage, I’d had no seat time in the car, I wasn’t driving well and it wasn’t particularly fun,” he says. “Tim Harvey was in the sister car and was consistently a second or so quicker than me, not a lot around Le Mans – but I didn’t enjoy that, either! At about five in the morning I felt the engine tighten. I mentioned this to Ray Bellm when I handed over, because we didn’t want a 30 grand rebuild on our hands. Ray did a couple of laps, then came in, concurred with my analysis and agreed that we should park it. At that point I had a flash of inspiration and decided to retire.

“I have been extremely fortunate, given that I wasn’t ever properly committed to the sport. I never went near a gym, I never stopped drinking on the eve before a race, I never stopped smoking like a chimney – and have only stopped now because doctors told me I had to. I wouldn’t want to be a racing driver today, given the monastic lives so many of them seem to lead. If someone had said to me, ‘You have to make a decision: you can either go on drinking and smoking, or else be a racing driver,’ I know which I’d have chosen.

“It wouldn’t have been motor racing.”

Born 18/4/40, Enfield, England

1961 Tests brother’s Austin A40 1962 Starts competing in MG TF 1963 Switches to Morgan Plus Four 1964 Le Mans debut, Deep Sanderson 1965-69 Raced Minis in the BSCC; class champion in ’68 1970-72 European F5000 1973 Production saloons, Ford Capri 1974 BSCC, Plymouth Hemicuda 1975 F5000, one win; BSCC, Ford Capri 1976-80BSCC class champion, Ford Capri 1980 Class winner and 3rd overall at Le Mans, Rondeau 1981 3rd at Le Mans, Rondeau 1984-85 WSCC, Tiga 1986-88 WSCC, Spice 1985 & 1987-88 Le Mans class winner & Group C2 champion