Lunch with Sir Jackie Stewart

For his final lunch, Simon breaks bread with a giant of the sport – triple world champion, F1 team owner and businessman par excellence

James Mitchell

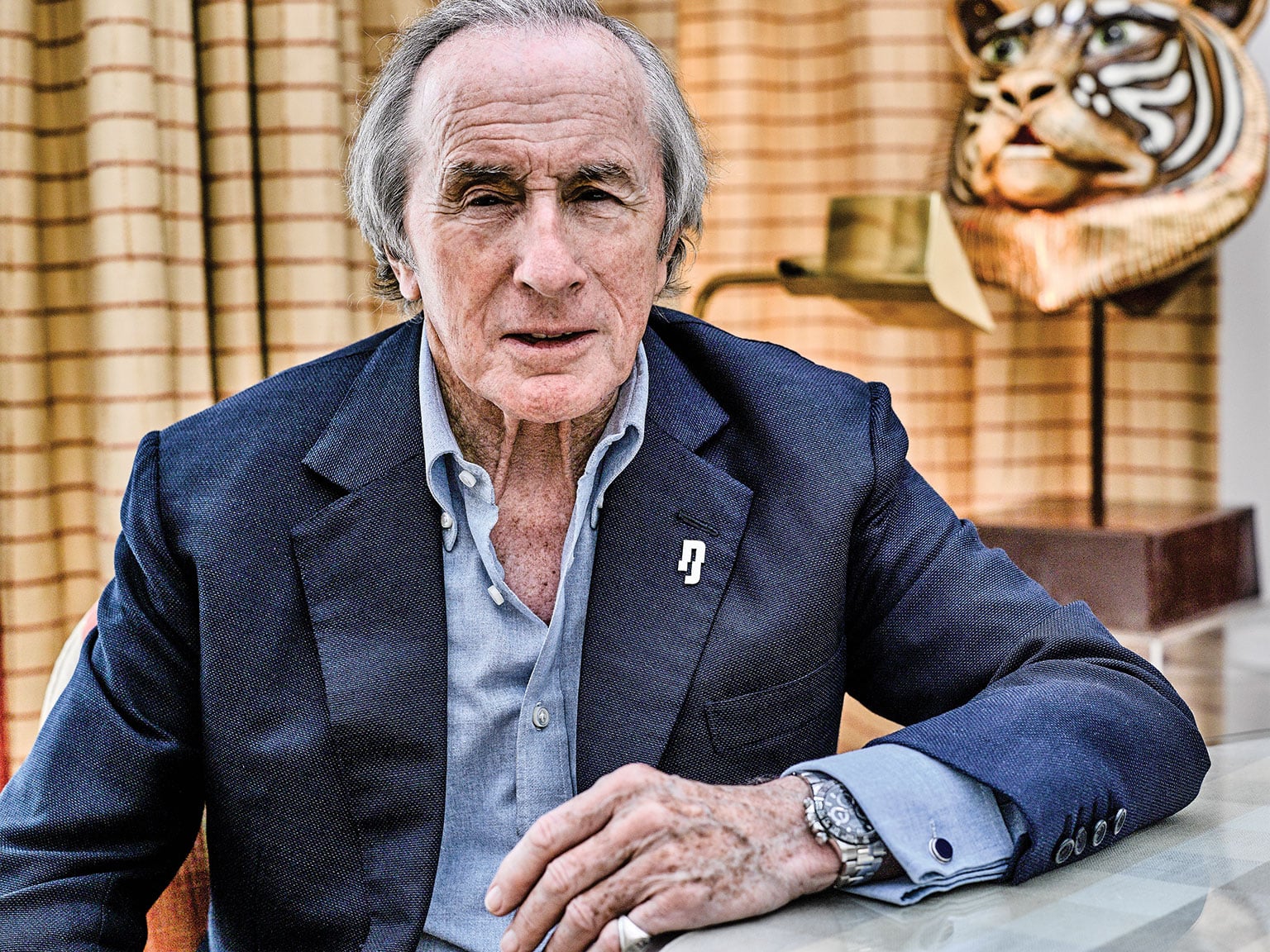

By almost any measure, Jackie Stewart was the greatest racing driver of his era. Now, more than four decades after he hung up the white helmet with the tartan band, Sir Jackie remains a familiar figure. It’s not just because memories live on of his three world championship titles in five seasons, or his 27 Grand Prix wins out of 99 starts. It’s also because of his continuing presence in the public eye: his visible friendships with sporting heroes, businessmen, musicians and royalty; his 40-year worldwide role with the Ford Motor Company; his work as an ambassador for brands from Rolex to Heineken; and of course his three-year stretch as the creator and motivator of his own Formula 1 team. Now he’s back in the news with his launch of a trust to search for a cure for dementia after Helen, his beloved wife of 54 years, began to develop the condition.

The details of Jackie’s racing life, how he spent his 11 seasons as a driver, are well known. But aside from his four-wheeled achievements, this is a complex man who admits that he is still, with millions in the bank and a knighthood, driven by feelings of inferiority and a fear of failure.

So I proposed that I should take him to lunch to talk about the man rather than the race results. He responded by inviting me to his home in Buckinghamshire. Every house he and Helen have had – their first little bungalow in Dumbuck, his place on the borders of Lake Geneva at the height of his F1 career, now this comfortable mansion where they’ve lived for the past 20 years – has been called Clayton House. He originally devised the name to combine his two early passions of clay pigeon shooting and driving a car at over the ton.

The current Clayton House stands in 150 acres of fine countryside. The lawns are immaculately mown, the hedges geometrically clipped, the horticultural machinery in the crisp barns is as clean as race-ready single-seaters. Scattered around the lush grounds are 47 wooden seats, each carved with the name of a past racing figure whom Jackie has known. A few commemorate men like Fangio and Prof Watkins, but the majority are in memory of friends and colleagues – from Jo Siffert to Bob McIntyre, from Mark Donohue to Roger Williamson – who during Jackie’s life have died racing.

Young hopeful tries Tyrrell’s F3 Cooper, 1964

Motorsport Images

The house is hung with a startling collection of paintings: two Lowreys, a massive Landseer portrait of Sir Walter Scott which dominates the hall, even – astonishingly – a small Turner. Jackie is also fond of modern Scottish painters, and their work is liberally displayed. Several dramatic Zurini automotive sculptures are on view but only a few trophies, just those that are especially cherished among the hundreds that he won. The rest are stored in the outbuildings with all the rest of what Jackie dismisses as his “junk”, along with a pair of Stewart F1 cars that he has retained and the Tyrrells, 003 and 005, that won him two of his titles and which he has bequeathed to his sons Paul and Mark.

There is a large dining room, but we eat in the more informal surroundings of the conservatory. Our meal is cooked and served by the Clayton House staff: Jackie employs 18 people to run his business life, the house and the estate. We start with Scottish smoked salmon from the River Spey, followed by chicken in mushroom sauce and strawberries and cream. Afterwards there are chocolates and camomile tea.

It’s all a long way from Dumbuck and the little house next door to his father’s small garage. “It had two bedrooms, my parents in one, my brother Jimmy and me in the other. I lived there until I was 23, when I moved out to get married to Helen.”

Jackie was about nine years old when he realised he wasn’t like the other kids at Dumbarton Academy Primary. “When it was my turn to stand up in front of the class and read from a book, I couldn’t do it. All I saw on the page in front of me was a dense jumble of letters. The teacher said I was dumb, I was thick, I was idle. The other kids taunted me. I can’t describe the shame and humiliation I felt.” After twice failing his 11-plus young Stewart had to leave the Academy. At 15, to his relief, he left school to work on the pumps in his father’s garage.

“When I married Helen I hadn’t told her that I couldn’t read or write. All through my career as a racing driver, even though I was making speeches at dinners, doing deals, appearing on TV chat shows, I still felt inadequate in anything to do with words. My inferiority complex meant I had to try harder at everything, pay attention to every detail, just to keep up with everyone else. I developed a photographic memory, so that I could recite every corner on every circuit, every braking distance and gear-change point, even for the Nürburgring.

“Years later, when my younger son Mark was 12 years old and struggling at his school near our home in Switzerland, his headmaster suggested he had learning difficulties which should be investigated. In London, after 20 minutes of tests, the specialist told us: ‘Your son is dyslexic.’ I didn’t know what he was talking about, but when he said it was often hereditary I asked to be tested too.

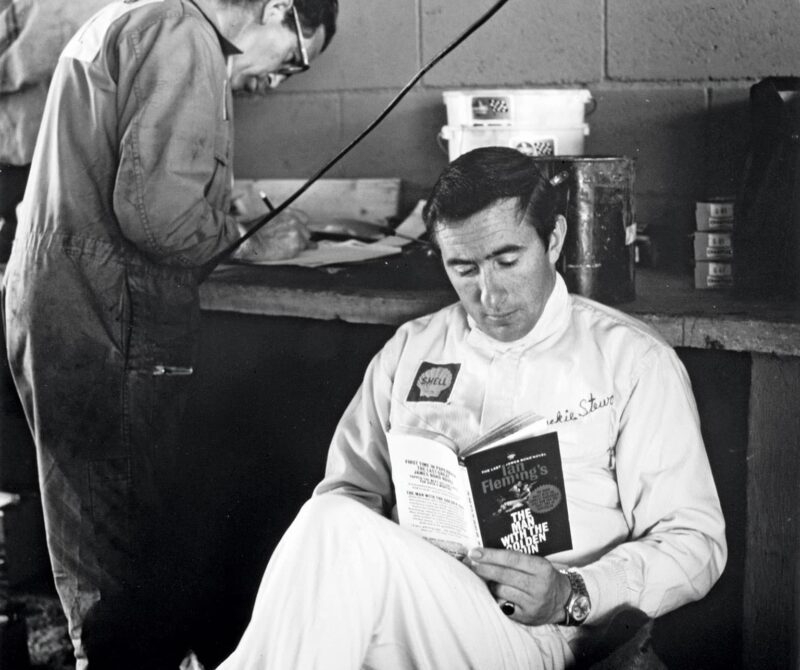

Reading Ian Fleming, but words didn’t come easy for JYS

Motorsport Images

“And so, at the age of 41, I was diagnosed as severely dyslexic. In 1948 the phrase ‘learning difficulties’ hadn’t been coined, and nobody at Dumbarton Academy had heard of dyslexia. All my life I’d been drowning, and now I’d been thrown a lifebelt. I wasn’t thick and stupid after all. I later learned that many successful sportsmen are dyslexic: Muhammad Ali, Steve Redgrave, Carl Lewis, Duncan Goodhew, Sandy Lyle, a long list. When they finally find they are good at something they put into it more passion, more pain, and they succeed.” Typically, Jackie has thrown himself into publicising dyslexia, becoming president of Dyslexia Scotland, and helping to get £1.4 million of state funds allocated to educating universities and teachers’ colleges about the condition.

“To this day I can’t use a computer or an iPhone, I can’t find the letters on a keyboard to tap out my own name. I can’t recite the alphabet past P. One of my PAs goes through my correspondence with me every day, and I dictate my replies. My book Winning Is Not Enough, which runs to 550 pages, took me several years, talking every word into a voice recorder.

“Back in 1954, swapping misery at school for a job in my dad’s garage gave me a different focus. Aged 15 all I was good at was cleaning the floors, washing cars and serving petrol. But I decided to do those jobs as well as they could be done. If I served a customer with his petrol faster and cleaned his windscreen better I’d get a tip. I earned more in tips than I did from my wages, and by the time I was 17 I’d saved up £375, enough to buy myself a brand new Austin A30. I didn’t know it, but that was to be the only car I ever bought with my own money.

“What rescued me was clay pigeon shooting. My father was a good shot, and he set up a small hand trap in our back garden and let me use his 12-bore. When I was 15 I won my first-ever shooting competition, got a huge trophy and £5, and that completely altered my self-confidence. I shot for Scotland, and then Great Britain. I kept shooting until motor racing came into my life at 23. It taught me the first rudiments of mind management. In shooting, if you lose a target you can’t get it back. When I started racing I realised it was just the same: if you make a small mistake you won’t get it back. Every corner, every lap, had to be perfect.”

1970: Ford powers Jackie’s March, and his future career

Motorsport Images

Jackie took his first steps in racing when a wealthy customer at the garage, Barry Filer, offered him drives in local events in his Porsche Super 90, and then a Marcos. He went well, and David Murray, whose team Ecurie Ecosse had run his older brother Jimmy some years before, put him in their Tojeiro-Buick and Cooper Monaco sports-racers. His speed in these rather elderly machines caught the eye of Ken Tyrrell. Tyrrell was running the works Cooper-BMC Formula 3 team, and his chosen drivers for 1964 were Timmy Mayer and Warwick Banks. Then Mayer was killed in the Tasman race at Longford, and Tyrrell had a seat to fill. Jackie was summoned to Goodwood for a test.

“I’d never driven a single-seater, and I didn’t know anything. Bruce McLaren, lead driver in the Cooper F1 team, did the first laps to set a benchmark. Then, after Mr Tyrrell had told me sternly to play myself in gently, I went out. After three laps he called me in, looking displeased: ‘I thought I told you to take it gently!’ I did some more laps, then Bruce did some more laps. Typically Ken played his cards close to his chest, didn’t give me any times. But John Cooper, watching at Madgwick, came running back and shouted to Ken, ‘You’ve got to sign that boy!’ I found out later that I’d beaten Bruce’s best time.

“Ken drove me back to his house for afternoon tea and said, ‘I want you to drive for me. I’m going to offer you £10,000 a year [a huge sum of money then, especially for F3] and you have to give me 10 per cent of your earnings from prize money and bonuses for the next 10 years.’ This rocked me on my heels a bit, so I said, ‘What if I want to keep the prize money and the bonuses?’ He said, ‘Then I’ll pay you £5 a year.’ That was the minimum sum then for a legal contract. I went home to Helen – we had no money at all, nothing except our bungalow – and we discussed it. I phoned Ken back and said, ‘Mr Tyrrell, I’d like to take the £5.’

“Two weeks later I had my first outing for him, the opening round of the F3 championship at Snetterton. It poured with rain. It was only a 10-lapper, but I won by 44 seconds, and took home £186.” All that season Jackie was virtually unbeatable, winning the British F3 Championship and European races at Monaco, Zandvoort, Reims and Rouen. “At the end of the year I’d made £10,000, so I reckoned I’d given Ken the right answer.

“That October I went to the Earl’s Court Motor Show, which is where deals got done in those days. On the Ford stand I was drooling over a creamy white Zodiac with chrome wheels and red upholstery. A man leant on the rail next to me and said, ‘How do you like it?’ I said, ‘It’s fantastic.’ He said, ‘I’m Walter Hayes, and I know who you are. If you sign a contract with Ford I’ll give you that car, and £500.’”

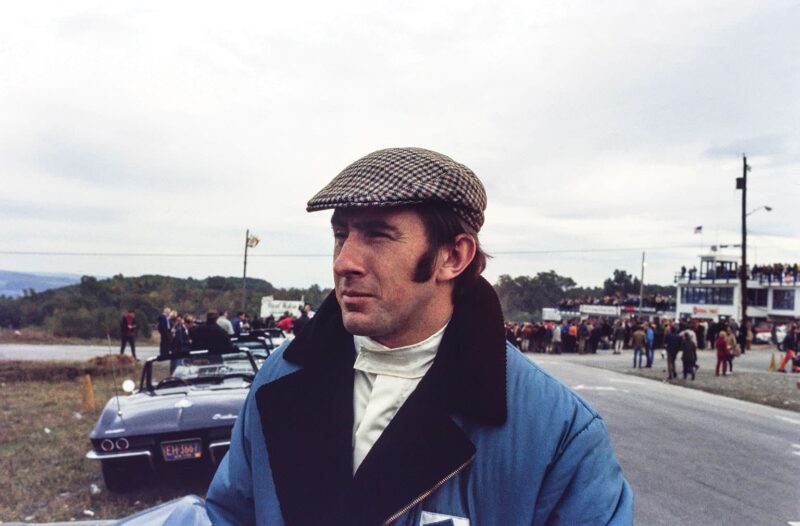

1973 US GP would have been Stewart’s century, had it not been for death of team-mate Francois Cevert

Motorsport Images

It was a very shrewd move by Hayes, who was Ford’s director of public affairs and the man charged with changing its image from cheap and dreary to virile and high-performance, using initiatives like the Cosworth DFV F1 engine and the Lotus Cortina. His deal with Jackie lasted from 1964 to 2004, and involved Jackie in much more than publicity work. By the end his contract stipulated 52 days a year, much of it testing pre-production prototypes and preaching vehicle dynamics to the technical staff in Detroit.

Jackie’s F3 success inevitably brought Formula 1 offers, and for 1965 – still only his second season as a full-time professional racing driver – he joined BRM as No2 to Graham Hill. He finished in the points in his first Grand Prix, was on the podium in his next three, and won his eighth, at Monza, finishing third in the world championship. “Jim Clark was world champion again that year. Since my first days in racing in Scotland Jimmy had been my hero. He helped me a lot, and we became very close. At one point we shared a flat in London. In those days drivers relaxed together, and Helen and I went on holiday with Jochen and Nina Rindt and Jim and Sally Stokes, who was Jim’s main girlfriend at the time. Jim was clever: he had a lot of girlfriends, and he managed things so that each of them thought she was the only one.”

Jackie’s perfectionism, and his determination to hide his problems, made him concentrate on every detail out of the car as well as in it. “Graham taught me so much. He was a very good public speaker, and I watched how he did it. He had a little black book with all his jokes written down. I couldn’t do the black book, but I got some good jokes and remembered them. Graham always dressed well: he told me you had to go to Savile Row to get a good suit. I found Kilgour, French & Stanbury were a bit constipated, so I went to Doug Hayward. You’d go in there and there’d be Roger Moore getting new suits, or one of the Rothschilds. Racing drivers have big necks and I have short arms, so I went to Jermyn Street to get my shirts made, and I got George Cleverley to make my shoes. He made shoes for everybody, from Winston Churchill to Danny Kaye. He worked until he died at 92, but the firm is still going, and I’ve never bought a pair of shoes from anyone else.”

Jackie began to grow his hair very long, which was the norm for rock stars then but unheard of among racing drivers. Was this, I ask, done for marketing and image reasons, the 1960s equivalent of Lewis Hamilton’s tattoos and bling? No, says Jackie somewhat unconvincingly: it was just that when he moved to Switzerland he had a different man to cut his hair.

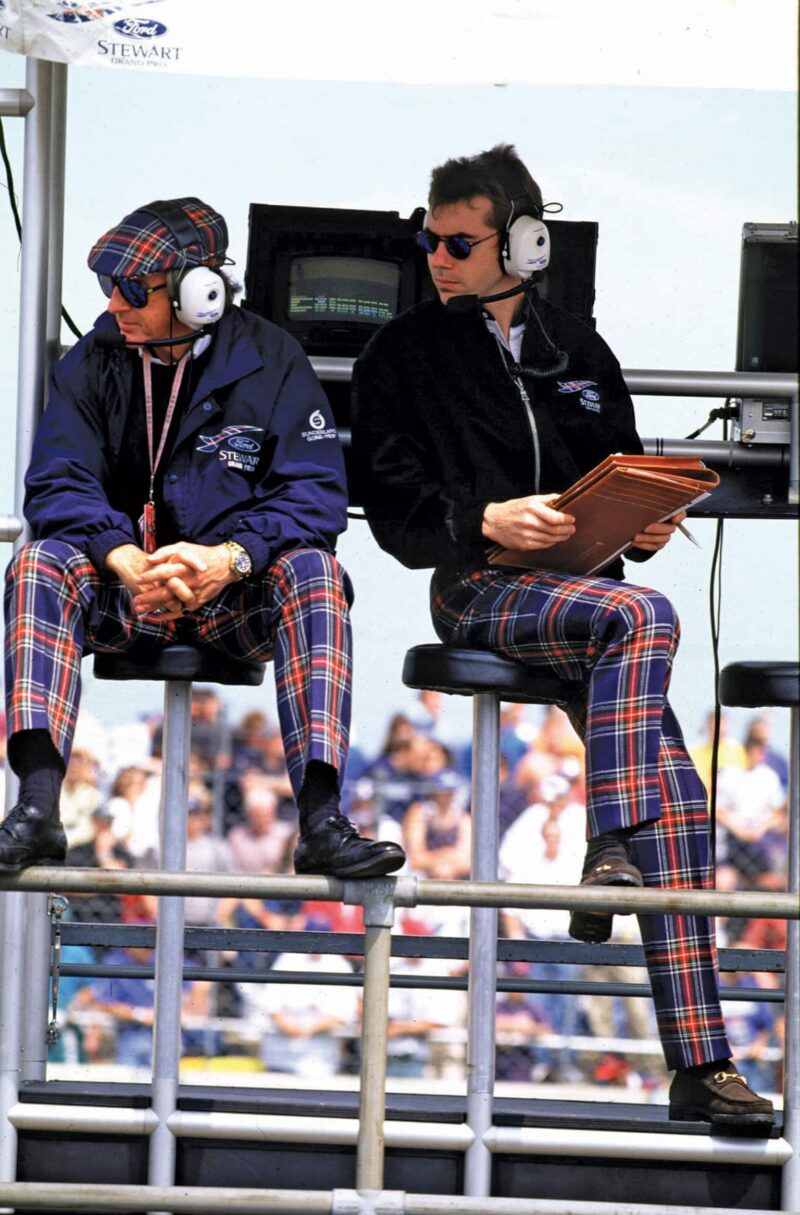

JYS was reluctant to become an F1 team owner, but Ford persuaded him

Motorsport Images

Jackie did three seasons with BRM. In 1966, three weeks after scoring a great win at Monaco, he had the worst accident of his career at Spa. During the first lap of the Belgian Grand Prix, going through the Masta Kink at around 170mph, he hit a river of water and aquaplaned off the track. He hit a telegraph pole, demolished a hut, and ended up trapped in the wreckage soaked in fuel. Incredibly, there was no sign of any marshals or emergency crews. Fortunately two other drivers who had gone off at the same spot, his team-mate Hill and Bob Bondurant, came to his rescue. Hill had to borrow a spanner from a spectator’s car to remove the steering wheel and get him out. It was half an hour before he was taken on a grubby canvas stretcher to the so-called medical room, where the floor was littered with cigarette ends. This accident, which could so easily have been fatal, convinced him that drivers needed to insist on safety facilities at all circuits being improved.

By 1967 BRM’s star was on the wane, and the heavy H16 was a great disappointment. Jackie was now also racing in F2 for Ken Tyrrell, who was running the British arm of the French Matra team as a prelude to his Formula 1 ambitions. These were realised in 1968, when Ken hired Jackie to race the V8 Cosworth-powered Matras while the French team ran their own V12 cars.

Jackie’s three Grand Prix victories that year included an unforgettable day at the Nürburgring when, in dreadful conditions of fog and rain, he beat the rest of the field by more than four minutes. Despite missing two rounds because of a wrist injury he finished second in the championship. From 1969 the Tyrrell/Stewart partnership clicked into overdrive, and in the next five seasons, first with Matra-Ford and then with Tyrrell’s own chassis, Jackie was champion three times.

With racer son Paul, core of Stewart Grand Prix

Motorsport Images

Throughout his career he was always a prodigious worker, racing when time allowed in everything from sports and touring cars to the Indy 500. He persuaded Goodyear to give Tyrrell an exclusive tyre testing contract, going to South Africa in the winter and doing two full Grand Prix distances a day at Kyalami, every day for two weeks. “Every lap had to be under the record to understand fully the behaviour of each compound and construction.

“As well as F1 for Tyrrell, I was making public appearances to honour my contracts with Ford, Goodyear and Elf, I was doing stuff for Moët champagne and Rolex, and I’d also started working on American TV as a commentator for ABC’s Wide World of Sports. Plus I was racing in the Can-Am Series for Carl Haas in that L&M Lola, which was a terrible thing. I only won two races in it. I’d fly from wherever the Grand Prix was to wherever the Can-Am race was, I’d go straight from the plane to do a public appearance at a shopping mall, then do a dinner that night, and be at the track next morning for practice. After the Can-Am race I’d have to rush to catch the first plane out and make it to the next Grand Prix. Police escorts to the airport never quite seemed to work, and I found the quickest way through the crowds was to persuade an ambulance man to give me a ride, siren going, lights flashing. With all that and the work for Ford and Goodyear and ABC TV, in 1971 I crossed the Atlantic 87 times. But I won the world championship again, and that season I earned a million pounds, quite a sum in those days. But I also contracted mononucleosis and developed an ulcer, although I only missed one Grand Prix while that was sorted out.”

Jackie was now devoting a lot of time and energy to racing safety. He reckons that, during his 11-season career, 57 drivers died in different types of racing. “In 1968 there seemed to be no end to it. On April 7 I was in Spain, ironically inspecting the safety provisions at the Jarama circuit, and I got the shattering news that Jimmy had been killed in an F2 race at Hockenheim. Exactly one month later, May 7, my former team-mate Mike Spence died at Indianapolis. A month after that, June 8, Lodovico Scarfiotti was killed in the Rossfeld hillclimb. One more month, July 7, Jo Schlesser was burned to death in the French GP at Rouen. And four weeks after that I was racing in that wet German Grand Prix at the ’Ring. After I’d taken the chequered flag and come back to the pits my first words to Ken Tyrrell were: ‘Is everybody OK?’

“I decided that Formula 1 drivers had to make their voice heard. There were some simple things that could be done, not very expensive things, that could make the tracks safer. And the marshalling and medical facilities at many circuits desperately needed to be improved. I was in the best position to take a stand. I’d been making my views felt ever since Jimmy’s death, and the fact that I could then go out and win at the ’Ring in the wet showed that I wasn’t making a noise because I couldn’t win races. I was making a noise because I didn’t want any more people to be needlessly killed.

BRM F1 seat in 1965 came about after just a year of F3

Motorsport Images

“I made myself very unpopular, with the race organisers, the track owners, the governing body the CSI, even with the journalists. Denis Jenkinson on your Motor Sport, hugely respected and about the best writer of all on F1 racing, dubbed me and the drivers who agreed with me ‘milk and water’ racers. Even Ken Tyrrell wasn’t happy, because he thought I was burning myself up with all this stuff. A lot of the drivers were shy of publicly saying they agreed with me, and one or two actually believed I was wrong. Jacky Ickx, for one, thought I was being unreasonable. But the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association, made up just of us F1 drivers, elected me their president.”

In 1969 four more drivers with F1 experience were killed: Lucien Bianchi, Paul Hawkins, Moises Solana and Gerhard Mitter. Then 1970, and on June 2 Bruce McLaren died testing his Can-Am car at Goodwood. Less than three weeks later Piers Courage was burned to death in the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort. Taking all levels of motor sport into account, in that spring and early summer a shocking total of 17 racing drivers were killed in just four months.

“A few days after Piers’ death most of the F1 drivers came to London for Bruce’s memorial service at St Paul’s Cathedral. Afterwards we all gathered in [BRM boss] Louis Stanley’s suite at the top of the Dorchester Hotel. I said, ‘Look, this is ridiculous, we can’t go on like this.’ Jochen Rindt had just come back from inspecting the Nürburgring ahead of the German Grand Prix, and he’d asked for a few reasonable changes: marshals with fire extinguishers around the circuit, run-off areas in a couple of particularly dangerous places.

It wasn’t as though we were asking for Armco barrier on both sides of an entire 14.5-mile track. But the circuit people refused to do anything. Nothing at all.

Stewart in ’68, the year before his first title

Motorsport Images

“I said, ‘If we put up with this and go to the ’Ring we’ll have no power to influence any other track to spend any money on safety. We mustn’t go.’ That didn’t go over at all well: most of the members didn’t like the idea of a boycott. So I called for a vote. I said if I was outvoted I’d resign from the GPDA, because I couldn’t condone going to the ’Ring when they’d refused to do anything at all. It was looking like I would lose, then just before the vote was taken Jack Brabham stood up. ‘Jackie’s right. If we don’t refuse to go, we’re out of it.’ That swung the vote, and we agreed that I should tell the organisers of the German Grand Prix, which was six weeks away, that we wouldn’t race at the ’Ring.

“There was a hell of a row. In those days 375,000 people used to come to the German Grand Prix, and it was important to the economy in the Eifel region. I had death threats. But of course they couldn’t run the race without us. It was hastily moved to Hockenheim for that year, and by the following year the Nürburgring lot had made most of the changes we’d asked for.

“But then in September came that black Saturday, Jochen Rindt’s death at Monza. Jochen and I were very close, and Helen and Nina are still best friends. The Rindts were our neighbours in Switzerland, and Jochen used to spend more time in our house than he did in his own.

“It was Saturday practice. I was in the pits about to go out, and Peter Gethin, who was driving for McLaren, came in and said ‘Jochen’s had a big shunt, it doesn’t look good.’ I rushed to race control, and they told me he was being brought by ambulance to the medical centre. When I got there they were bringing Jochen in on the back of a VW pick-up thing. His injuries were terrible. He never liked wearing the crutch straps on his seat belts, and he had submarined forward in the impact. There was a lot of blood, but he wasn’t bleeding. So I knew his heart wasn’t beating, and I knew he was dead.

Mementoes include Stewart and Tyrrell F1 cars

“I still had to go out to set a grid time. I was in the car waiting for Ken to send me out – I was still in the blue March 701, because the first Tyrrell wasn’t ready – and I pulled down my visor and burst into tears. Then I had to go out, and it was like throwing a switch. I had a job to do. The concentration kicked in and I did three laps, qualified on the second row. Then I came back in, got out of the car, took off my helmet, and burst into tears again. Somebody gave me a bottle of Coca-Cola, I drank it, and then I did something totally out of character for me. I smashed the bottle against the wall, shards of glass everywhere. In the car I was in control, out of the car I was not in control.” The March shouldn’t have been a match for the Ferraris, but in the race the next day Jackie led the slipstreaming group for 17 laps, and finished second.

During 1973, as it became increasingly clear that he would be world champion again by a comfortable margin, Jackie decided it would be his last season. He told Ken in confidence, but didn’t tell Helen because he didn’t want her to be counting down, race by race, to his retirement. In the Stewart household the dangers could never be forgotten. “Jo Bonnier was another close neighbour in Switzerland, and our elder son Paul, aged seven, went to the same school as little Kim Bonnier. Two weeks after Jo was killed at Le Mans, on the school bus Kim said to Paul, ‘My daddy’s dead, and your daddy’s going to be next.’

“The final Grand Prix of the season, at Watkins Glen, would be my 100th, which seemed like a good point to finish. François Cevert had been my No2 for four seasons, and he’d become my friend, my protégé, almost my younger brother. Ken had decided he would be the team’s No1 for 1974: he’d told me, but he hadn’t yet told François.”

Two weeks previously in the Canadian Grand Prix at Mosport Cevert had tangled with Jody Scheckter, hurting his legs, and it was decided that he and Jackie should spend a few days in Bermuda so that François could recuperate before Watkins Glen. “We stayed in this beach club, and most of the other guests were rich Americans who were, let’s say, no longer young. The place was like a morgue. So on the third day, sitting in the dining room at dinner with everybody talking in hushed tones, François saw a piano in the corner and said, ‘I’m going to wake them up a bit.’ As you know, he was a brilliant pianist, and he launched into some loud boogie-woogie. This didn’t go down at all well, and some of the old dears were summoning the management to get him to stop. So he moved seamlessly into Beethoven’s piano sonata No8 in C minor, The Pathétique. After that they all adored him.”

At Watkins Glen the accident happened during Saturday morning’s practice. Tyrrell was running a third car for Chris Amon, and when Jackie came over the brow and saw the road strewn with blue bodywork, he assumed it was Amon who had crashed. “Then I saw Chris walking towards me beside the track. I slowed and gave him an enquiring thumbs-up, but he gave me a grim-faced sign back. That meant it must be François. I stopped, got out of my car and ran towards the wreckage. Jody was walking back towards me, and he said, ‘Don’t go there, you don’t want to see.’ But of course I had to, he was my team-mate. It was a terrible sight, his body was horribly mutilated. I stood there two feet from him, in total shock. Ken withdrew the team from the next day’s race, and my career as a racing driver was over.”

Ten years later, when Paul was 17, he announced that he wanted to be a racing driver. Jackie and Helen were dismayed, but Paul was adamant, and in the end Jackie decided that, once Paul had finished university in America, the best way to approach it was to do it properly. Paul Stewart Racing was launched with all the Stewart efficiency, and fielded cars in the single-seater formulae for a variety of drivers as well as Paul, including a young David Coulthard.

“PSR won 13 championships, but Formula 1 was a big step. What happened was the Ford Motor Company was involved in Formula 1 with Sauber, and wasn’t getting anywhere.

“In 1995 I was flying to Dearborn on one of the Ford private jets with Jac Nasser, soon to be the president of Ford, plus Neil Ressler, the company’s chief technical officer. They asked me what I thought they should do. I said: ‘You should get out. You’re not going to win anything with Sauber.’ They said they had to stay in, because their international dealer network felt it was important.

“So I said I’d run an F1 team for them. They could put up the money, and I’d do it for cost plus 10 per cent. They said, ‘The board will never agree to Ford owning an F1 team. You should do it yourself.’ I wasn’t keen on that, but Paul liked the idea, and I got talked into it. I told Ford I’d do it if I got the engines for nothing and they paid half the driver costs.

“So Stewart Grand Prix happened, with Paul as chief operating officer and me selling the sponsorship. We had HSBC, Hewlett Packard, Lear Corporation, Texaco and others, and we were very well-funded. In the three years we ran the team we never lost money. In fact we made £5 million profit every year. In our fifth Grand Prix, Monaco, Rubens Barrichello finished second. In our third season we were fourth in the Constructors’ Championship ahead of Williams and Benetton, and Johnny Herbert won us the German Grand Prix.

“Then Ford said they wanted to buy the team. I didn’t want to sell. I wanted a family business that Paul and I could grow. But they kept coming back. First they offered $100 million. I still said I wasn’t selling. Then they raised their offer to $130 million, and we went with that.

“Under Ford it was a disaster. The cars were painted green and branded as Jaguars, but over five seasons it never really worked. Neil Ressler ran it first, but had to return to America when his daughter got very sick. He appointed Bobby Rahal, who had run a good Indy team, but was lost in F1. Then they tried Niki Lauda, but he was rarely ever there. Then it was Tony Purnell, who’d been running an electronics company that Ford had bought. In the end Ford sold it to Red Bull for almost nothing. And Red Bull has done rather well with my old team…

“People say Formula 1 must have been better in my day, the good old days. But they were the bad old days: look how many people got killed.

“On the whole I think Bernie [Ecclestone] has been good for Formula 1. It wouldn’t be what it is today without him. But some things are difficult to agree with – like the threat of losing the British Grand Prix. Bernie says, if you can’t pay we’ll go somewhere else, there are lots of new places that will pay. But the new places don’t have the heritage, the history. Formula 1 needs a British Grand Prix, it needs Monaco, it needs a German GP and an Italian.

“If I were at the top of Mercedes today, I’d get out now while they’re on top. It can’t get better, and they can’t afford to be second. Remember what they did in the 1950s: come in for two years, win everything, walk away. But if I was Honda, I’d stay in until they become real winners. They have massive resources, and there’s an awful loss of dignity for them, and for McLaren. They must stay until they get it right.

“As for the Lewis and Nico thing: in my time you never needed to try to out-psych your team-mate because there was usually a proper No1 and No2. At BRM I was number two to Graham, and sometimes I beat him, but he was never the prima donna, he never once played a card against me. I don’t approve of the public wrangling between those two, and I blame the team for that. It wouldn’t have happened under Ken Tyrrell.”

Now Jackie is working full-time on his new trust. He calls it Race against Dementia, and he is pursuing it with all his usual energy, determination and attention to detail. “I’ve put in £1 million to start it off. A pharmaceutical billionaire who has just sold his company has put in £1 million. This week a well-known businessman put in £100,000. The website is getting lots of hits, people are sending in fivers and tenners, which is really wonderful. We’ve put together a really good advisory group to ensure we use the money fruitfully, and we’re looking for a medical Adrian Newey or Gordon Murray to drive the research.

“Around the world there are 45 million people suffering from dementia, and now that people are living longer there is a one in three chance that you will get it in your lifetime. The cost of caring for dementia sufferers in this country is more than the cost of caring for sufferers of heart disease and cancer combined.

“It’s an epidemic, and a cure has got to be found. This is the most important thing I’ve ever done in my life.”