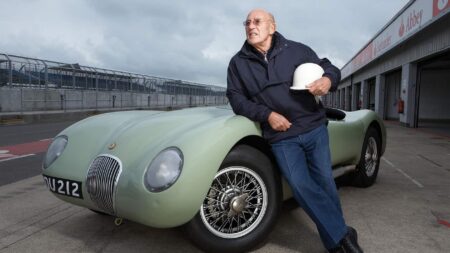

The name of Monaco Motors might not be familiar, but that of the man who ran it undoubtedly will be. Although John Wyer would go on to be probably the greatest team manager in the history of sports car racing, back in 1948 the Monaco Motors payroll comprised Folland and his wife Joy, Ian Connell (who would co-drive with Folland in the race), Wyer and his wife Tottie. Such were the traditions of the times that the ladies were responsible for cooking and timekeeping, Wyer was team manager and first mechanic with Connell as second driver and second mechanic. As first driver, Folland alone had but one task, which Wyer considered fair enough on account of him being the owner.

In the 2-litre class two opponents were more noteworthy than others. First was a brand-new works Aston Martin in a team run by John Eason-Gibson (whose job Wyer would soon inherit and in time bring Aston the World Sports Car Championship and outright Le Mans win it so craved). This first post-war Aston was a pure prototype, the first car conceived under David Brown’s patronage and the first of a line that would only retrospectively come to be known as the DB1. It had a unique body and St John Horsfall and Leslie Johnson at its wheel. The other car was Luigi Chinetti’s 2-litre Ferrari 166 V12, which not only looked and sounded amazing but would set fastest lap before retiring. Folland was much taken with it.

At first the race went brilliantly for what can now be referred to as Red Dragon. Wyer’s policy of determining the precise speed at which the Aston could safely be driven and ignoring everything and everyone else soon paid dividends as, in typically filthy Spa weather, the car climbed the leaderboard throughout the night, its vast fuel tank allowing it to run four hours between fills. But the works Aston was doing similarly well, too. As the last changes approached, Eason-Gibson suggested the two Astons did not fight each other but worked together to ensure a one-two finish with, of course, the factory car coming first. Folland and Wyer reluctantly agreed, only to see the works car increase its pace to extend its lead. Wyer protested; Eason-Gibson pleaded ignorance. But Wyer reckoned his car was quicker and knew it would not need another fill, the two advantages being enough to cancel out the works car’s half-lap lead.

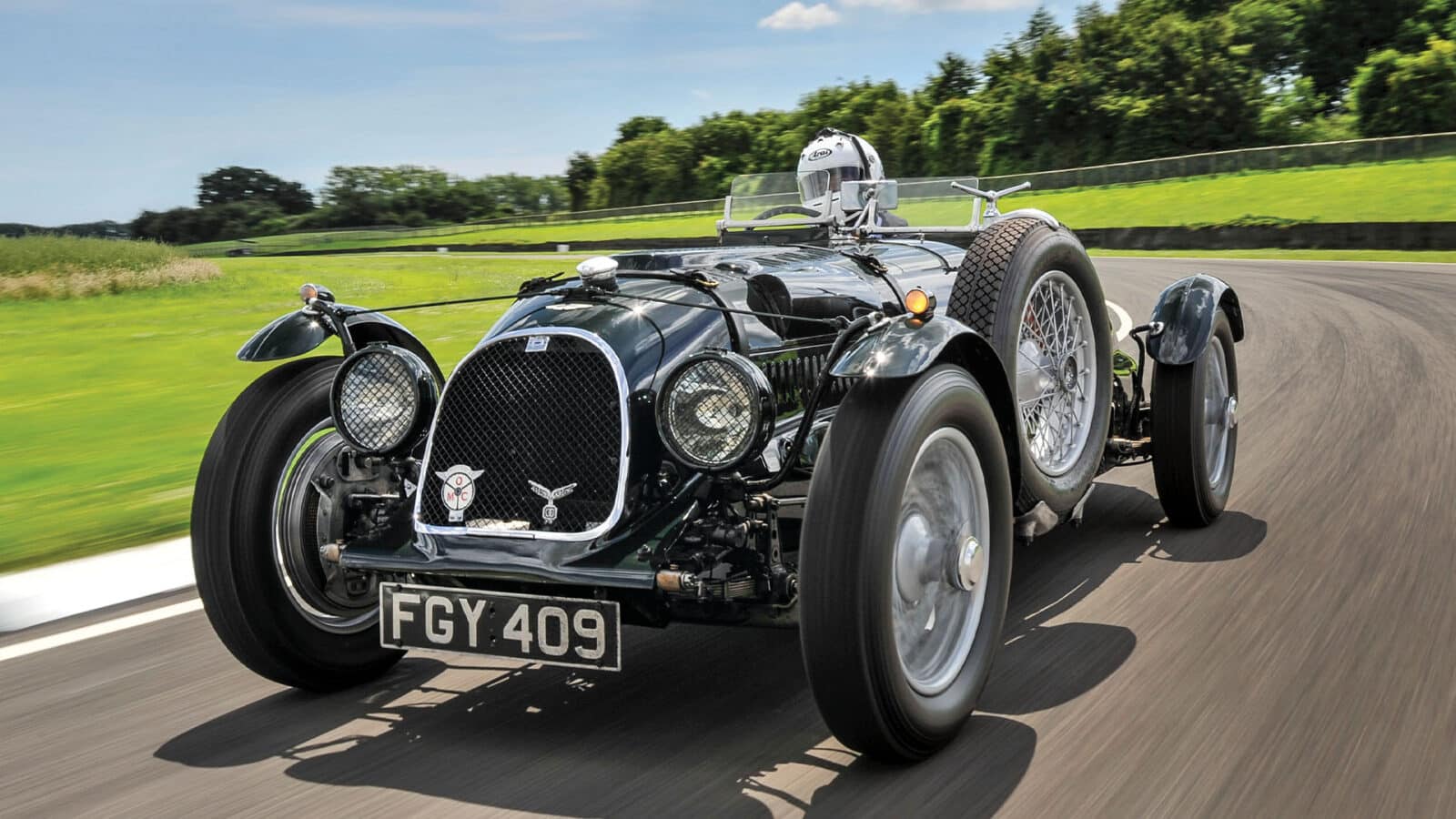

Cockpit looks more Twenties and Forties

Stuart Collins

In the end, however, as Connell pulled away for the last time, the vast fuel tank split, pouring petrol over the rear tyres and causing the car to spin at Eau Rouge, off the track and down a bank into an unrecoverable position. The race was lost, but under the circumstances Connell had good reason to be thankful not to suffer an ending far less happy than this. Two months later the duo took Red Dragon to third at the Montlhéry 12 Hours. The following year Folland was joined by Anthony Heal to race Red Dragon at Le Mans, a dozen years after its debut there, but once more engine failure thwarted the team.

If you look at Red Dragon now and compare it to images taken in its heyday you’ll not struggle to spot that it appears today in somewhat different form. In fact it looks rather more like an early Ferrari than a late pre-war Aston Martin. This is not a coincidence. Chinetti’s performance in the Ferrari 166 at Spa in 1948 had not gone unnoticed and Folland became determined to have one of his own. In January 1949 Wyer and Folland travelled to Italy, met Mr Ferrari and Ingegnere Lampredi and negotiated the purchase of the 166 Spyder Corsa raced by Nuvolari in the previous year’s Mille Miglia. Sprayed green and wearing Welsh dragons, the Ferrari took victory in the Lavant Cup at Goodwood first time out with Folland driving, and he then modified the original Red Dragon’s bodywork into the 166-mimicking form it carries to this day.