“In the history of grand prix racing, there’s one era when I wish I’d been an adult and that was the 1960s,” he says. “It was such an amazing period, actually not just for racing but for life on this planet. There was so much change going on. People got liberated.

“Looking back on ’66, you had two of Dad’s previous team-mates in Dan Gurney and Bruce McLaren coming out with their own grand prix cars to try and become the first to win a championship in a car of their own production.” But it was Jack who was ahead of the game.

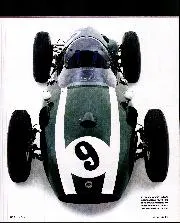

He was supposed to be winding down the driving by this time, thanks to the pincer pressures of his age and a burgeoning customer racing car business. He had Gurney and promising Kiwi Denny Hulme to hold the front line – until Dan left to form Eagle. As F1’s ‘return to power’ 3-litre era dawned, this was no time to throttle back. Armed with an American-sourced V8 tuned by old contacts at Repco, mated to a typically no-nonsense spaceframe from his plain speaking partner Ron Tauranac, Brabham was ready to make hay. The rule change, despite a three-year notice period, appeared to catch most on the hop – especially when Coventry Climax made the shock announcement that it wouldn’t play to the new capacity. Yes, Colin Chapman and Cosworth were sowing the seeds for the DFV, but that was more than a year away from bloom. Meanwhile Ferrari had its heavy, sports car-derived V12, but with John Surtees at its head Maranello was still well placed – until politics pushed the ’64 champion over the edge. After his final win in red at Spa, he walked and pitched up at past-its-best Cooper.

Brabham consequently stormed through the summer, claiming four grands prix in a row – the French, British, Dutch and German – to lay hold of an unchallenged crown.

Brabham was successful first with Cooper, then his own eponymous team

Bernard Cahier / Getty Images

The perception has lingered that Brabham’s achievement in ’66 is undervalued in comparison to the feats of others such as Clark during the same era. Perhaps it’s the ‘interim’ nature of that Grand Prix season, as teams scrabbled for short-term, or at least severely compromised, power solutions. Jim Clark’s Lotus, for example, was hobbled first by a Climax engine of only two litres, then by BRM’s hulking (and unreliable) H16; likewise Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart in the constructor’s works cars. But rather than undermine Brabham’s success, his nous to develop a winning package should enhance it – and as ever, his ability behind the wheel couldn’t be underestimated.

“Brabham was a pioneer in more ways than one”

“As a driver, my own purple patch – where I was at such a level that whatever car I drove I felt I could beat anyone – was 44,” says David. “The same age that Dad retired. When I turned 40 I looked at what Dad achieved at the same age in ’66 and it blew me away: how he was able to focus on the business, focus on the race team, develop the cars in all the formulas, then jump into a grand prix car – against guys who only raced, remember. And they were bloody good, too, the likes of Clark, Graham Hill and so on.