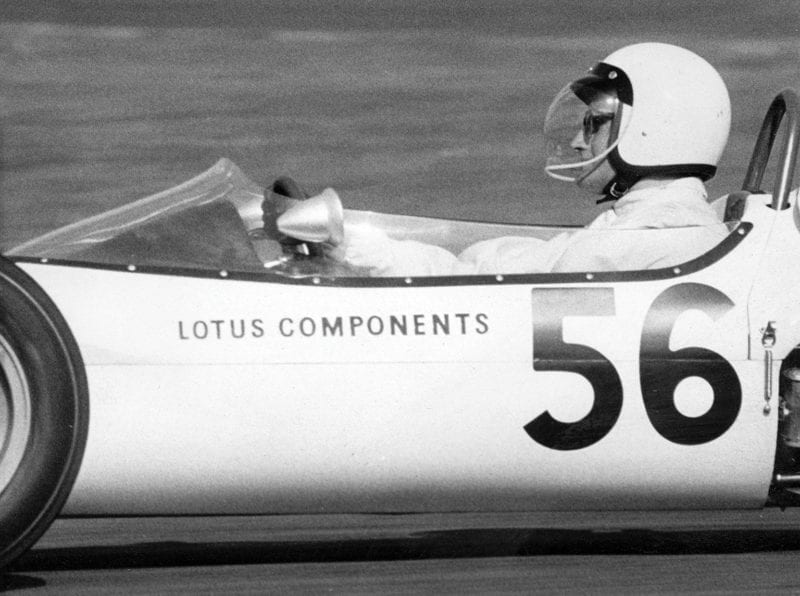

“I tested it at Snetterton, and the thing was undriveable. Awful. It would spin, very slowly. It had so much inertia in all that drive train – the drive shafts, the diffs front and rear and the central diff, all of which had to speed up and slow down in response to throttle and brake. And once you’d started to slide it was gone. They took me to the French Grand Prix, so that was my first F1 race, and it did its usual trick of melting the fuel pump.” John did four more Grands Prix with the 63: at Silverstone a long pitstop failed to cure gear selection problems, so with the car jammed in third gear he droned round to finish 10th and last. Monza, Mosport Park and Mexico all brought retirements, but in a fine effort he qualified at the Canadian track halfway up the grid. “It went well there because Mosport is all fast sweeping curves, where stability is important. That’s why the 56 4WD turbine car worked well at Indianapolis, because in that environment you haven’t got the delicate balance all the time between throttle and steering, you’re committed to one balance.

“But on twisty tracks it was a disaster. It was long and heavy, and slow down the straights because of transmission power losses. The improvement in F1 rubber meant that you didn’t have any more grip than the 2WD cars, because of the understeer. So Chapman put more and more torque through the rear wheels, which turned a car which might have had some potential as a 4WD car into a terrible rear-wheel-drive car.” At the end of 1969 season the 63 was consigned to history. Its sensational replacement was the Lotus 72.

“The thing about Lotus was – perhaps it’s the engineer in me – if you wanted to be somewhere where there was new stuff going on all the time, where there was excitement and you were at the spearhead of design, Lotus was the place to be. Chapman was a great opportunist, and his designs were in many respects extremely elegant, for example using one bracket or one pick-up point to do several jobs. I found him very inspiring, and when he was in inspiration mode he could get anybody to do anything.

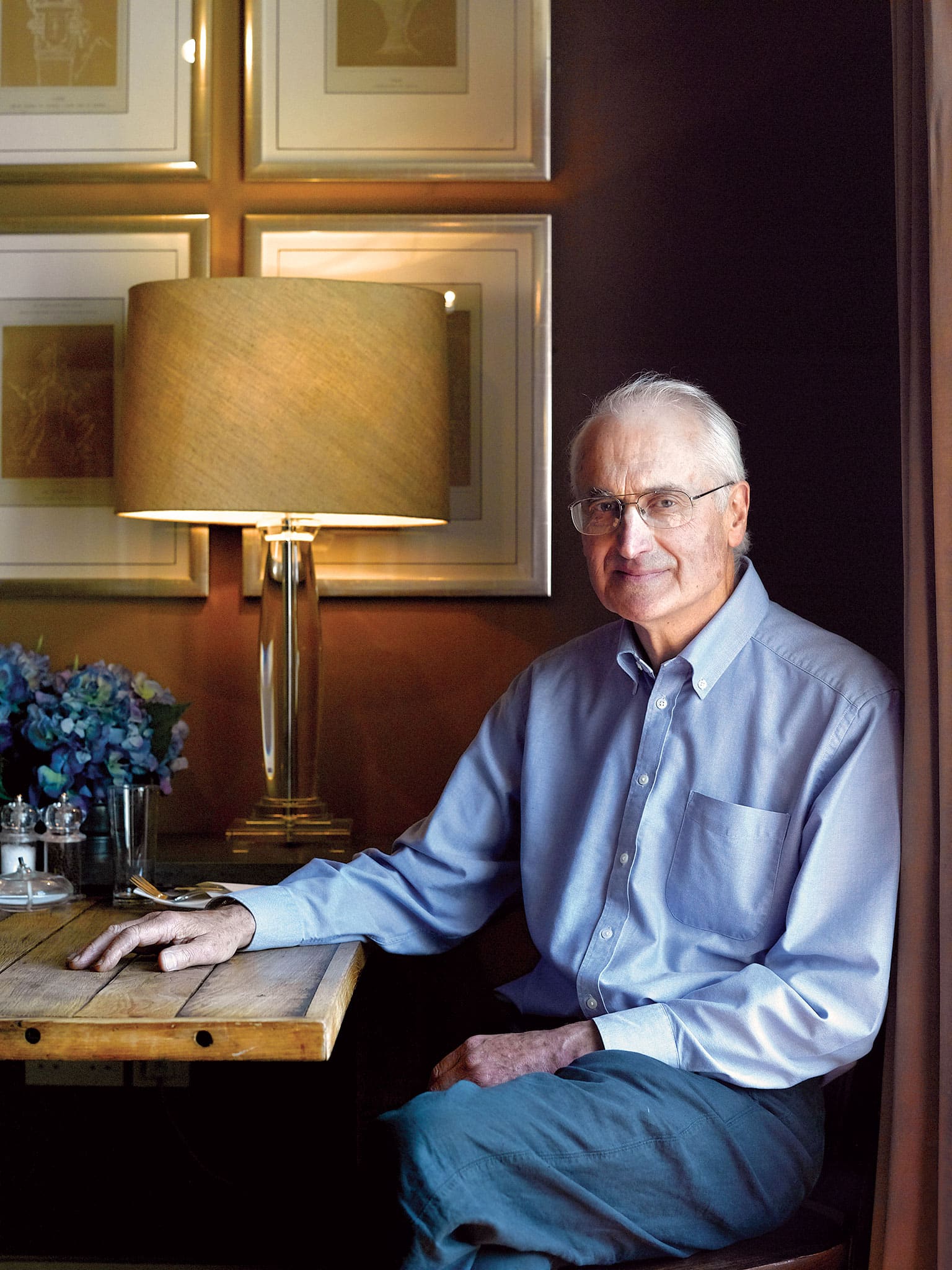

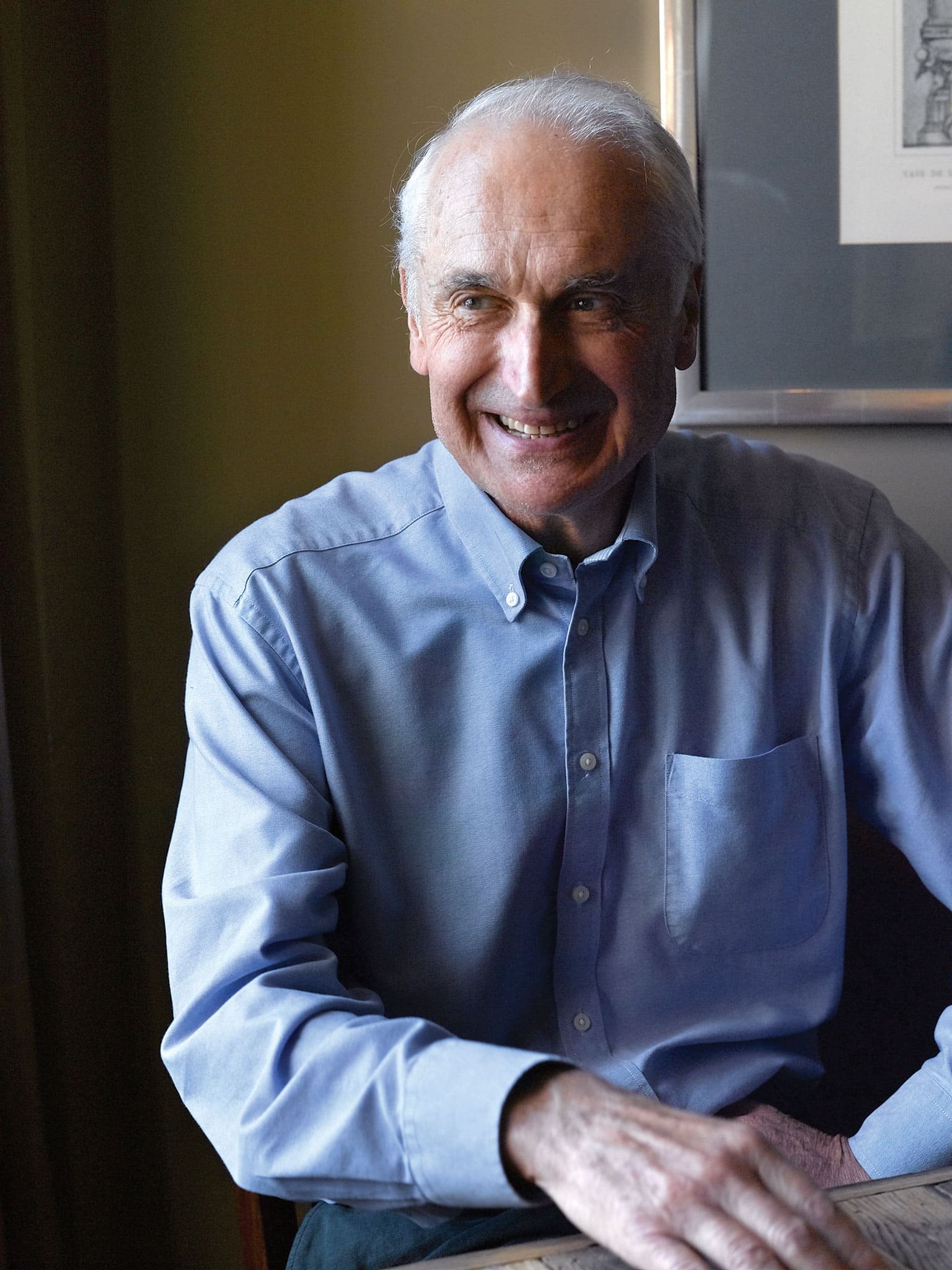

Back at Lotus in the 1990s, with Herbert and Hakkinen, both “lovely guys”

Motorsport Images/Sutton

“But once he had an idea he pursued it to the death, and he would argue that black was white. If I’d had more experience, and the knowledge I have now, I could have stood up to him when we went through the debacle of the anti-dive and anti-squat suspension on the original 72. But I was only 25, with less than half an F1 season under my belt. Chapman wanted someone who would race for Lotus and not ask any questions. He’d say. ‘They’re my cars, you don’t tell me what to do with them’. And I wasn’t part of Chapman’s inner circle. I had no money at all: he paid me £300 a race, and out of that I had to pay my own expenses. Once, flying back from a race, I was so broke I had to ask him if he could give me some money. He pulled a big roll out of his pocket, peeled off a few notes and gave them to me. He regarded me as a sort of grease monkey.

“I don’t think Maurice Philippe, who had to interpret Chapman’s concept and do the detail design, was in a position to stand up to him either. But once they got rid of the antis, and going into the Fittipaldi era when they’d put it together properly, the 72 was a great car.

“Towards the end of the 1969 season, at Watkins Glen, Graham Hill had the accident which broke his legs. He wasn’t deemed to be fit, so I found myself No 2 in the F1 team to Jochen Rindt. In fact Graham signed for Rob Walker and did a full season. I was sent to South Africa to do winter tyre testing in the 49, and by the time we got to the South African Grand Prix I’d had quite a lot of time in it. I finished fifth, with Graham sixth in the Walker 49.

“I got on very well with Graham. We flew to lots of places together, and he was very supportive. I think he identified with me as somebody struggling along, just as he had done in his early days. Jochen, on the other hand, kept his distance. He’d make a sarcastic comment and then retire to Bernie’s motorhome and play gin rummy. He didn’t see me as F1 material. He was probably right. Somebody said I didn’t look like an F1 driver, I looked like a geography teacher, and I should have been wearing a chalky tweed jacket with leather elbows.

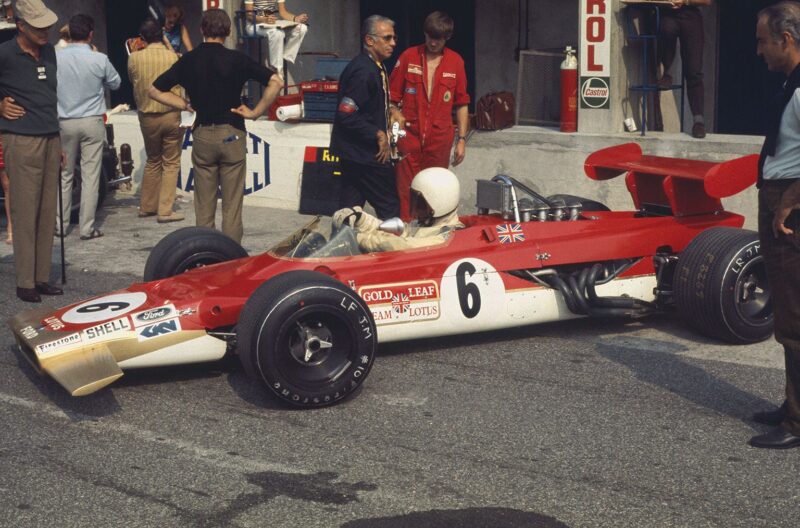

“The first time I raced the 72 was in Spain, and it was so bad I didn’t qualify. It was no better at the Silverstone International Trophy, where I started from the back of the grid. Jochen was just in front of me, qualifying slower than some of the F5000 cars. The car had done no testing, and it had mega amounts of anti-dive and anti-squat. The angled suspension links provided resistance to braking dip and acceleration squat, so when you put the brakes on you were trying to jack up the front. If you have more than 100 per cent anti-dive, as the 72 had, braking at 1G you could take the front springs off the car and nothing would happen, because all the longitudinal loads were being absorbed by the links, not the springs. The braking grip was terrible and there was no braking feel at all, no sensation of anything happening until you saw the front wheels locked and smoke pouring off the tyres. The same under acceleration: the thrust was still going through the top radius arm, but it was also trying to jack up the back of the car, so the suspension locked up and you got no traction.

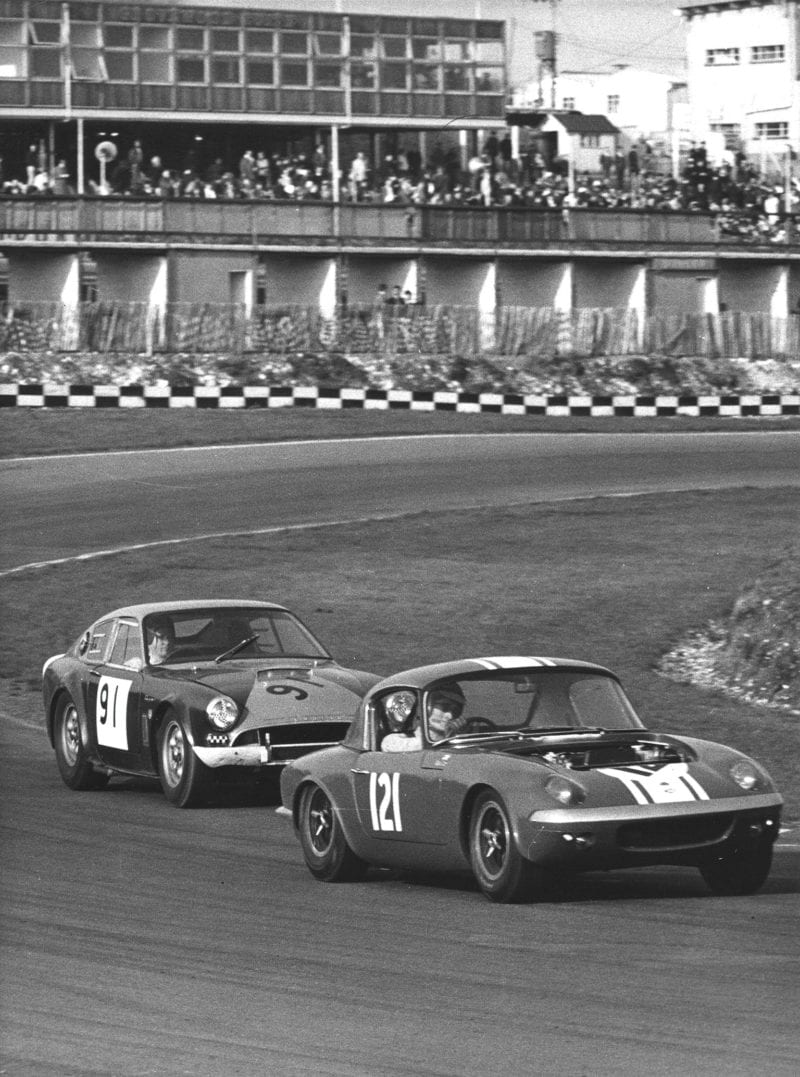

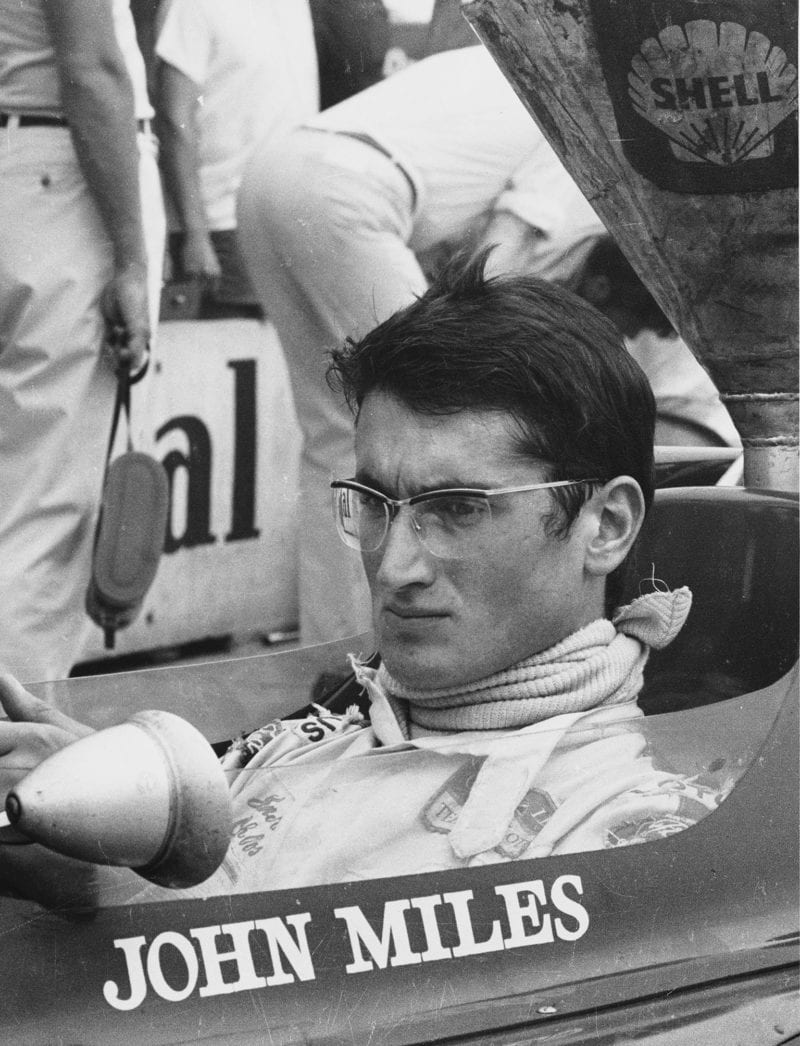

Miles struggled with dead duck Lotus 4WD 63 until Chapman moved on to other ideas

Motorsport Images

“Jochen said to Chapman, ‘I don’t like it, and I’m not driving it’. After the Silverstone disaster Tony Rudd, who was then engineering director on Lotus road cars, told Colin he’d tried anti-dive at BRM years ago and the drivers hated it. Somehow he was able to persuade Colin to bin it. Then there was a typical Lotus panic. The whole monocoque had to be changed, and it turned into a huge saga. They altered it in stages, and the first time I got a fully parallel car was at Zandvoort in late June. That was Jochen’s first victory in the 72. I qualified eighth, and ran sixth until I spun five laps from the end and John Surtees’ McLaren got past. By then the car was falling to bits.