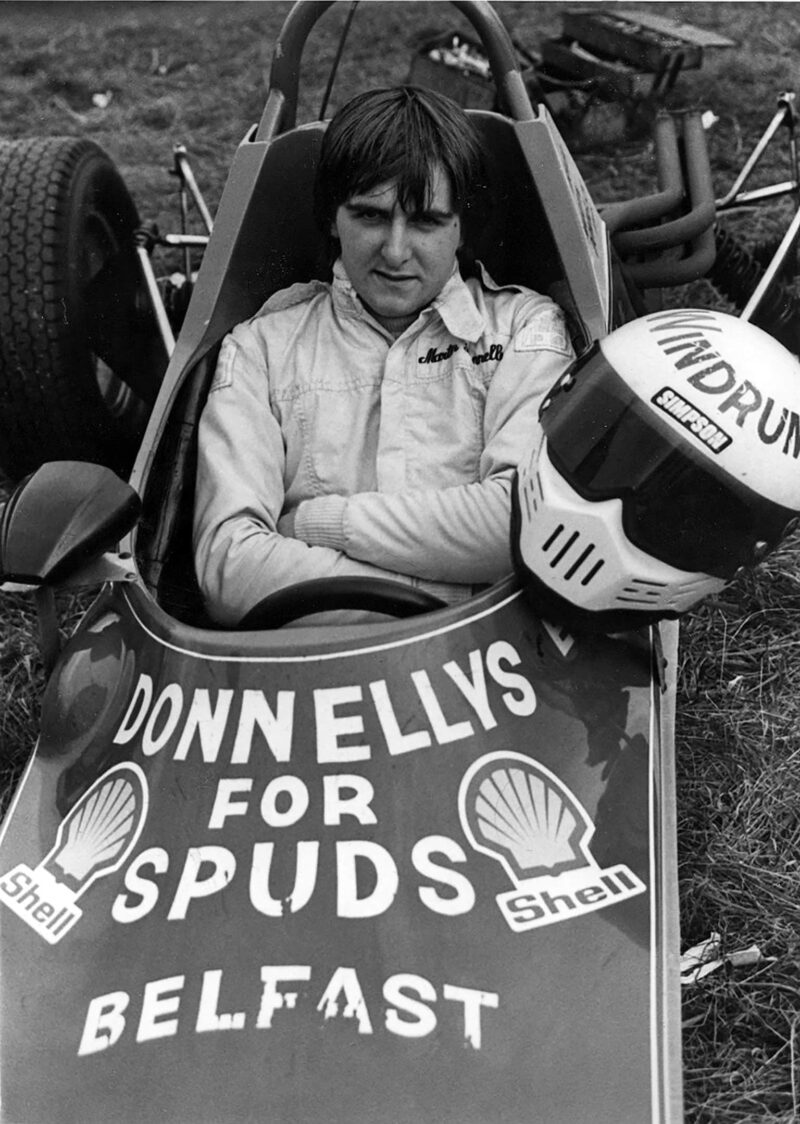

Lunch with... Martin Donnelly

The Irishman was a star graduate of the junior leagues, which is where he earned a living after the horrific accident that ruined his Formula 1 dreams

James Mitchell

A hot, dusty afternoon in southern Spain. It’s September 28 1990, Friday qualifying at Jerez. With eight minutes left, Jean Alesi’s Tyrrell has just produced a ripple of interest in the press room by setting a surprise quickest time. The McLaren-Honda of Ayrton Senna and the Ferrari of Alain Prost, World Championship rivals, leave the pitlane for a late run. Nigel Mansell trudges in, helmet in hand: his Ferrari has stopped out on the circuit with an electrical problem. The session, even for the teams, has a slightly relaxed feel. There’s always Saturday to find another half-second.

Then, abruptly, everything stops. Silence falls, that heavy ominous silence which always means there’s been a bad accident. At the startline the red flag is shown. From my vantage point in the press room I can see across to the back section of the track, and those two very fast right-handers. A Minardi, undamaged, is stopped broadside across the track. In front of it there is wreckage, strewn over a long distance. Beyond it, a bundle is lying in the middle of the track. People are running towards it. Professor Sid Watkins’ medical car is already accelerating out onto the circuit.

The scraps of bodywork in the scattered wreckage are yellow. Camel yellow, worn by Lotus. But Derek Warwick’s Lotus-Lamborghini V12 is in the pitlane. It has to be Martin. Ever-cheerful Irishman Martin Donnelly, so far a strong 14th fastest out of the 30 runners, must be that bundle. It couldn’t look worse.

But, almost exactly 20 years later, it’s Martin sitting opposite me in the Mulberry Tree restaurant at Attleborough. He seems fit and well. His scatter-gun speech delivery, his deadpan Irish humour, are as they always were. It’s only when he walks that you notice his left leg is stiff, and one of his shoes has a built-up sole. He shows no resentment about the accident that destroyed a promising Formula 1 career in its first full season. He continues to work in motor sport – it’s all he knows – and still lives in Norfolk, close to Snetterton, where he arrived 26 years ago as a naïve but determined Irish lad to start his professional career. In fact, racing has been a force in his life from the cradle.

“My father loved it all his life. Where we lived in West Belfast wasn’t far from the Dundrod circuit, and as a boy he’d go up there across the fields and hedges to watch the racing. He saw Moss and Fangio and Hawthorn in the 1955 TT, they were his heroes. He had a vegetable business, sold to the shops in the city and supplied the schools. Never had much money, but he was a hard-working man. Up at 3am, three cups of coffee and four cigarettes and out the door. He was a terrible man for the smoking. The bed was full of burn holes where he’d fallen asleep with a fag going. His road cars looked like ashtrays. That’s why I never smoked, I hated it.

“I went to the races from when I was in nappies. He’d work down the market Saturday morning, finish at midday, pick me up, drive his Sunbeam Rapier or his Hillman Imp to Kirkistown. Tape up the headlights and paint numbers on the doors, go racing. It was more an excuse for him to be with his mates, Archie Phillips, Duncan Macken from Donegal, big Dave, George Windrum, Harry Johnson. They were all drinkers. The bar was a tent in the field by the paddock, cowpats up to the counter. Then they’d race over to Miss McBride’s little pub in Kircubbin, that was their special stage. Then on to the Wildfowler Inn at Greyabbey. By then they’d really be away. I’d sit in the car, and my dad would say, ‘See that young fellow in the Rapier there? Give him these crisps and orange juice for me.’

In 1985 Van Diemen for FF2000 with Frank Nolan backing

Motorsport Images

“By the time I was eight, while he was in the bar at Kirkistown after a meeting, I’d start his car, move the seat right forward and go round and round. I’d go steady past the pits in case anybody was watching, and then go hell for leather once I was out of sight. My dad had this idea in his head that when I turned 17 we’d go racing together. He was always a saloon car man, but he saw what Tommy Byrne, Mick Roe and Derek Daly had done, and he realised Formula Ford was the way to go. So he bought an ancient Crosslé to race until I was old enough, and then he’d pass it on to me. He tried it out at Kirkistown, but he didn’t like being so close to the ground, seeing the wheels moving up and down and the rain on his helmet. So he said to his friend Joey Greenan, ‘You race it, and when Martin’s old enough you can be his mechanic.’ Fine, fine, says Joey. So that Friday night Joey and I go down to Kirkistown, he does some laps, then he stuffs some coats behind me so I can reach the pedals, and off I go. The old man on the gate says, ‘There’s a couple of goats grazing round the back of the circuit, just keep an eye out for them.’ That’s how I got into single-seaters. I was 12 then.

“We lived in a rough area of Belfast, sectarian violence, youth gangs, people trying to get you for the IRA when you were young. My parents didn’t want that for me, so when I was 11 they sent me to a boarding school in the Republic, run by Irish priests. It was hard, and I was very homesick. They came to see me on a Sunday halfway through my first term, and my mother said, ‘Give it three years, and then if you still feel like this we’ll pull you out.’ So I thought to myself, bloody hell, I’d better just get on with it. It toughened me up, prepared me for coming to England later.

“You had to be 17 to race then, but when I was still 16 my dad and I worked out a routine. At a race when we signed on he’d say, ‘Show your licence’, and I’d say, ‘You’ve got it.’ He’d say, ‘No, you’ve got it.’ And I’d say, ‘I left it on the kitchen table’, and they’d say, ‘Well, we know who you are. Bring it next time.’ We’d just have to make sure we always signed on with a different official. So we got away with it.”

Once past 17 Martin did every event he could in the old Crosslé, all over Ireland. “One Bank Holiday weekend we managed four events: Kirkistown, Mondello, and the hillclimbs at Croft and Donegal. At Phoenix Park, against all the local heroes in their new cars, I led the opening laps. It was all good learning experience, and it was good craic for Dad and his mates. Then a builder called Frank Nolan stumped up five hundred quid to get us to the Formula Ford Festival at Brands Hatch. We wrote on the nose of the car, ‘With thanks to Frank Nolan’. I got a mention in Autosport, they called me the Belfast schoolboy.

Early FFord backing came courtesy of Donnelly Snr’s veg business

Motorsport Images

“My dad would drive from here to Timbuktu if he could help you out. But after a few Bacardi and cokes he could get a bit crude and rude, and sometimes he’d overstep the mark. One year when I won a race at Brands and he’d come over to watch, I went to the bar to find him after the race. His mates said, ‘Your dad didn’t see you race. He had a few too many scoops, got a bit friendly with somebody’s girlfriend and the boyfriend laid him out cold. We scraped him up and put him in the ambulance, nee-naw, nee-naw, he’s up to Sidcup Hospital.’”

The well-worn Crosslé gave way to a year-old Van Diemen with a borrowed engine. Martin won a lot of races in Ireland, and got through to the final of the 1982 FF Festival. Then he got a place at Queens University in Belfast to read Mechanical Engineering. “I’d been there two weeks when I got a phone call from Frank Nolan. Frank had built a lot of houses in the Republic, but he made his real money out of central heating. You’d give him the key to your house at 8 o’clock in the morning, come back at 8 o’clock at night and he’d be in and out, dusted, done. Most heating firms would come into your house and make a mess for a week. He wanted to give a young Irish driver the chance to go to England and take on the big boys. I said to Frank, ‘I’ll have to talk to my mum and dad.’ Dad couldn’t afford to help me any more, and Mum decided it would be better if I did it properly, rather than just race at weekends and drink away what they’d spent seven years of boarding school fees on. So we persuaded the university to hold my place for one year, and off I went to England. I never went back.

“When I got to England I went up to Norfolk and [Van Diemen boss] Ralph Firman and his wife Angie put me up while I looked for somewhere to live. I found an 80-year-old lady living in a bungalow who wanted some company. I paid £25 a week to stay in her spare room, big old bed, feather mattress. She fed me, darned my socks, took my phone messages. She was lovely, and I stayed there for four years. You won’t believe it, but her name was Mrs Happy Breeze.”

Backed by Frank Nolan, Martin moved up to FF2000 with a new Van Diemen, winning first time out at Cadwell Park, then at Donington and Brands. He also dominated the Irish championship, but mid-season there were queries about the legality of his Zagk-prepared engine. Nolan asked for a voluntary engine strip, and when the camshaft was found to be incorrectly modified he insisted Martin give up the 48 points he’d scored in the Irish series up to then. Starting mid-season on zero, Martin came through to win the title in the last round. In late 1984 he switched to a Reynard run by Rushen Green Racing, and won the BBC Grandstand Series.

The 1985 FF2000 season, both the British and Euroseries championships, developed into a head-to-head battle between Martin and the talented young Canadian Bertrand Fabi. Martin won at the Nürburgring and Brands Hatch, and was leading at Zandvoort when a cracked exhaust set the bodywork on fire. In the penultimate British round at Oulton he had to win to stay in the title hunt. “I took pole, led into the first corner, and Fabi hit me. We both went into the barriers, and he was champion. I could say it was deliberate contact, but if I’d been in his situation I’d probably have done the same. He was a hard competitor, focused on going all the way. For 1986 we were both moving into F3. In February Bert was testing at Goodwood for West Surrey and he went off. He died in hospital next day.”

F3000 debut in 1988, and a sombre win after Johnny Herbert’s accident

Motorsport Images

Martin’s first F3 mount was a Ralt run by Swallow Racing. The season was to cost £160,000, with £80,000 coming from sponsor British Telecom and £80,000 from Frank Nolan. But in April, after the first three rounds, Frank Nolan died suddenly. “He’d been a friend and mentor as well as a sponsor. A hard task-master, didn’t suffer fools, and used to write me letters saying if I didn’t produce the results he’d pull out. But he’d paid enough upfront for my F3 season to keep things going.” That year Martin had wins at Donington, Oulton and twice at Silverstone, and wound up third in the British F3 Championship. In the Cellnet Awards – successor to the Grovewoods – he won the top prize, ahead of Johnny Herbert and Gary Brabham. Things looked good for 1987, but they didn’t turn out as planned.

“Swallow had switched to a new Reynard, and we couldn’t get it to work. In the first six rounds I scored just nine points. Swallow said they couldn’t afford to keep running me if I wasn’t getting results, and I was dropped. I went to see Glenn Waters, who was running the Intersport Ralt-Toyotas for Damon Hill and Massimo Monti, and asked him to give me a break. He said he’d run me in the next round, which was at Thruxton, and then decide. I had a great battle for second place with Gachot and Herbert, and finished third, so Monti went back to Italy and I was in. We won at Oulton and Brands, pole and second place at Zandvoort, second at Spa, Silverstone and Snetterton. So after that disastrous start I was third in the championship.” In the second half of the season he’d scored more than twice as many points as Johnny Herbert, who won the title.

“Then we went out to Macau. In first qualifying I wasn’t feeling well, and I wanted to leave the big effort to the next day when the circuit would be well rubbered up. But my engineer Andy Thorby insisted I try for a good lap. So I did, and it was provisional pole. Overnight a typhoon arrived, qualifying was cancelled, and we were all holed up in the Hyatt.” Come race day, from pole Martin pulled away on the tortuous round-the-houses track to score his most important victory yet.

“That got me my first F1 contact: Peter Collins from Benetton asked me to do the Estoril test. And Marlboro tried me at Donington for Mike Earle’s Onyx F3000 team. I was quickest by half a second, but the drives went to Volker Wiedler and Russell Spence. So it was back to F3 with Intersport. But it was a really good deal, because Cellnet gave me and Damon a £10,000 retainer each, plus a £1000 bonus for a win and a free Ford Escort to drive around in. That was unheard of in F3 then. Plus we had free mobile phones. All the Brazilian drivers used to borrow them to call home.”

1989 proved more tricky. Donnelly lost Vallelunga because the Reynard’s nose cone hadn’t been crash tested

Motorsport Images

The six front-running British hopefuls were now known as the Rat Pack, and they had names for each other. Johnny Herbert was Little ’Un, for obvious reasons. Julian Bailey was Grumpy. Damon Hill was Secret Squirrel, because he played his cards close to his chest. Mark Blundell was Mega. Perry McCarthy was Mad Dog, after a character in the Catchpole cartoon strip. And Martin was Yer Man, because of his Irish habit of prefixing the term to anybody’s name. By mid-season he was running second in the British F3 Championship to JJ Lehto, ahead of Gary Brabham, team-mate Damon and Eddie Irvine.

Ex-F3 entrant Eddie Jordan was now in F3000, running his Camel Q8-sponsored Reynards for Herbert and the Swede Thomas Danielsson. “Mid-season Danielsson had to stand down because of an eye problem. EJ came to see me at the July F3 Snetterton, which I won from pole.” Martin slips effortlessly into a fine parody of Jordan’s fast-talking, expletive-ridden sales patter: “‘You’re the man, I’ve been watching you, I want you to drive for me, I’ll take you to the f***in’ top’ – the things he tells every driver. He wanted £30,000 to put me in Danielsson’s car for the last five rounds of the season. I said, ‘OK. I’ll get on the phone to Mrs Nolan.’ What EJ didn’t know was that Frank had died without making a will, and all his assets were locked up. I didn’t have a sniff of £30,000. Eddie gave me a contract under which he got 15 per cent of my earnings, but I thought 15 per cent of nothing wasn’t a bad deal, so I signed. Then he said, ‘Here’s the other contract’. It was with a company called Eddie Jordan Management, and it tied me in for six years. I thought, this is a bit of a scam, but I reckoned I had no choice, so I signed it. Then we went to the Bank Holiday Brands.”

The EJ Reynards qualified first and second, Herbert leading Donnelly until an accident stopped the race. At the restart Donnelly took the lead: behind him Herbert and Gregor Foitek tangled in that enormous pile-up which injured Johnny dreadfully. After a two-hour delay Martin took a sober win in his first F3000 race. A week later, in the Birmingham Superprix, he finished a close second to Roberto Moreno.

F1 debut with Arrows at Paul Ricard in 1989

Motorsport Images

“Now EJ was saying, ‘F***in’ great, you’re on your way, but where’s yer f***in’ money? Ye’re fleecing me.’ I just said, ‘I’ll talk to Mrs Nolan’, but of course I had no way of coming up with any 30 grand. Next round, at the Bugatti circuit, I was second again. Then Zolder: I started from pole and was leading when the gearbox broke. Final round, Dijon, I won. We’d spent nine weeks in F3000 and we’d ended up third in the championship. Now that EJ realised I was good for him, he stopped asking for money which he knew would never come and became my pimp, selling me for rides with poxy Japanese sports car teams. So he got his money that way. I reckon I hold the world record for pounds-per-mile earned in 24-hour races. Three races, £170,000-worth of EJ deals, and I didn’t do 10 racing yards. I did Le Mans for Nissan, with Grumpy and Mega. Lap five Julian crashes into a Jaguar at Mulsanne, out. Daytona for Jaguar with Patrick Tambay and Derek Daly: lap one, second corner, Daly comes off the banking and hits Mick Roe’s Nissan, Irishman against Irishman. Third one was Nissan at Le Mans again, gearbox broke on the warm-up lap.

“For 1989 EJ offered me £50,000 to stay with him in F3000. ‘Camel loves you, Marty, I f***in’ love you, just sign here.’ The contract said that 15 per cent of the 50 grand he was paying me had to go straight back to him. I said, ‘No, EJ, I won’t do it. You’re getting 15 per cent of everything else I’m getting, but you’re not going to get 15 per cent of your own money back.’ I was at the lawyer’s offices the whole day. He kept bursting in: ‘Have you signed it yet? This is your opportunity. Just f***in’ sign it. I can go with anybody else. Get me Massimo Monti on the phone. D’you know what ye’re costing me? This’ll be the greatest team. What’s the f***’s going on? Have you signed it yet?’ But I held out for the full £50,000. Took all day. So for 1989 it was me and Jean Alesi.”

The season started well: Martin outpaced the field at Silverstone until engine trouble intervened, and then won round two at Vallelunga – only to lose the win and the points because his Reynard’s nose hadn’t undergone the required crash test. He won at Brands, on the anniversary of his maiden F3000 victory, but otherwise he went backwards, frequently out-qualifying Alesi but losing points with tangles and thumps. Alesi took the title.

Scoring big points in 1987 F3 with the Ralt-Toyota

Motorsport Images

But now F1 was beckoning. For 1989 Peter Warr signed Donnelly as the Camel Team Lotus reserve driver alongside Nelson Piquet and Satoru Nakajima. Then in January Piquet was hurt in a fall on his yacht, and it seemed that Martin would get his first GP ride sooner than expected. “They flew me out to the test in Rio, and there was no way I was ready for it. Piquet and Nakajima were midgets, and the car was so small I couldn’t do 15 laps before getting cramp in my legs. I wasn’t fit enough, and in the heat and humidity I was gasping for air. Fortunately Nelson healed enough to do the race. But I carried on testing. For the Imola test I took along my friend Ed, who used to run Ed’s Café on the old A11 near Snetterton. In their FF days Senna, Gugelmin, Moreno, Guerrero, all those guys used to eat truckers’ food at Ed’s. We were walking past the McLaren garage and Ayrton came running out, gave Ed a big hug and said, ‘What are you doing here? Have you brought me my bacon sandwich?’

“At the pre-GP Silverstone test in June I made headlines in the weeklies because I was eighth fastest overall, quicker than Piquet. Then Derek Warwick hurt himself in a charity kart race. EJ was on the phone at once to Jackie Oliver at Arrows. ‘Jackie, have I got an opportunity for you, yeh, look at the Silverstone times, Marty’s the next kid on the block, yeh, he’s f***in’ mega.’ So I was in the Arrows for Paul Ricard. Jean was a bit ticked off, because he was leading the F3000 championship, he was a French driver, and it was the French GP. Two days later Michele Alboreto, who was driving for Tyrrell, had a problem because he was a Marlboro driver and Tyrrell were sponsored by Camel. So EJ makes another phone call. ‘Ken, have I got an opportunity for you, yeh, Alesi’s the next kid on the block, yeh, he’s f***in’ mega.’

“So we’re both at Paul Ricard for our first Grand Prix. I qualified 14th in the Arrows, Jean qualified 16th in the Tyrrell. At the start there was that huge pile-up with Gugelmin’s March up in the air. I didn’t think I’d hit any wreckage, but they found a kink in a wishbone, so I had to take the restart from the pitlane in the spare car. It was set up for Cheever and I found it very difficult to drive, with massive oversteer, and there was no drinks bottle. I plugged on and finished 12th. The Pirellis on the Tyrrell worked very well and Alesi had a really good race, finished fourth. He stayed with the team from then on. If EJ had made the first phone call about Jean and the second one about me a lot of things might have been different…

“But I did get my F1 drive for 1990. Lotus offered me £1 million for a three-year deal, which EJ thought was ‘mega’ as he was getting 15 per cent of it. But I’d been through the EJ School of Scams. I said I wanted one point two. Eddie was horrified. ‘This isn’t f***in’ F3, Marty. You’ll screw the deal.’ But I stuck to my guns, so EJ went back in and said to Fred Bushell, ‘Our driver says it’s not enough.’ In the end Warr and Bushell agreed to £1.2 million: £200,000 for 1990, £400,000 for ’91 and £600,000 for ’92. Warwick came over from Arrows, and I was his number two. He got £1 million just for one season. He was a hugely competitive man: very nice out of the car, sociable, fun, speak to anybody, but when he put on his helmet he grew horns. But I out-qualified him in six of the 13 races we did together, which gave me a bit of extra motivation.” Unfortunately Martin’s Lotus-Lamborghini only finished in five races, with a seventh and a couple of eighths.

Starting racing again with Martin Donnelly Racing Team

Motorsport Images

“Jerez was the last European F1 race of 1990, and things were looking good for 1991. EJ was coming into F1, and I was the first driver he ever offered an F1 contract to. But I said to EJ, ‘Why would I want to sign for you when you’ve got no F1 experience?’ On the Friday morning in the Jerez paddock I signed an option letter from Lotus and got a $40,000 cheque – separate from the retainer, to just guarantee my services. We went 10-pin bowling on Thursday night, and I had parma ham for dinner. That’s all I remember of that weekend.”

In the closing minutes of Friday qualifying Martin was powering through the fast right-hand sweeps at the back of the circuit when his front left suspension collapsed. At 140mph the Lotus speared head-on into the barriers on the left, and immediately broke in two. The front half disintegrated into scattered bits that were hurled along the left side of the track. The rear half came to rest some 60 feet away. The driver, his crash helmet split by the initial impact and with the back of the seat still strapped to him, was tossed like a rag doll to land on the track further on, his legs bent at impossible angles.

The next car to arrive was the Minardi of Pierluigi Martini, who quick-wittedly stopped broadside across the track so no other car could run over the inert form lying in front of it. All the other cars stopped behind. In his marvellous 1996 book Life at the Limit, Sid Watkins explains what happened next.

As soon as Sid got to the scene he opened Martin’s visor, and saw his face was turning blue from lack of oxygen. Clearly death wasn’t far away. Sid cut the straps to remove his broken helmet, and then forced apart his clamped jaws and got an airway in. Once Martin’s colour had started to improve, Sid set up intravenous infusions and then turned to his legs which were, to use Sid’s unemotional language, displaying “obvious deformities”. Having put these into inflatable splints, he got Martin onto a stretcher and into the ambulance to take him to the medical centre. Only now did Sid become aware that Ayrton Senna had been standing just behind him, silently watching everything that was being done. After an hour’s work in the medical centre, Martin was flown to hospital in Seville, Sid and his colleague Jean-Jacques Isserman in the helicopter with him. They worked on him until the early hours of the next morning. Among his other injuries, a scan showed severe bruising to the brain.

“The Lotus boys said when they went to get the car, most of it went in bin bags, shards of carbon fibre mixed in with syringes. As for Ayrton, he’d been watching a man he knew near death, bone sticking out of his legs. He told a journalist that seeing me like that made him realise how fragile we all are. Then he went back to the McLaren garage, got in the car, put his visor down, and when they ran the last eight minutes of the session he set the fastest lap anybody had ever done round Jerez.”

On Tuesday Martin was flown back to London and thence to the helipad on the roof of the London Hospital. At first things looked reasonably encouraging, but on Tuesday night he went downhill. On Wednesday he was in renal failure. There were also head and chest problems. Then came another blow: a torrential haemorrhage developed in one of his legs. Sid came under strong pressure from his medical colleagues to amputate, but he refused. It was six weeks before doctors were able to make his kidneys function again. Eventually the artery and the fractures started to heal correctly.

“I was in a coma for seven weeks, and when I started to regain consciousness my voicebox wasn’t working, because I’d had tubes down my throat for so long. So I never said anything. They were worried that I might have some brain damage. Then one day my fiancée Diane was sitting beside the bed, and a nurse came round to take some blood. When he put the needle in he hurt me. Apparently I grabbed him and said, ‘That f***ing hurts!’ and Diane said delightedly, ‘He spoke! He spoke!’

“As my consciousness came back I worked on getting better. I was really determined, because in my naïveté I thought I could go to Willi Dungl’s clinic in Austria and he’d do for me what he had done for Niki Lauda, get his magic wand out, wave it, and I’d be racing again in March. But I didn’t leave hospital until February 14, four and a half months after the accident. I wasn’t in a fit state to leave, but I went, in a wheelchair. Niki flew me to Dungl’s, and on the second day one of the physios came to my room and chained up my wheelchair. ‘Willi says you use crutches only now.’ I couldn’t stand up, but I went down to breakfast on my crutches. We did seven hours a day of different therapies and exercises. It was very hard work, but I stuck to it.” And in April Martin was able to walk down the aisle and marry Diane.

“But, after all that pushing and shoving, in the end I had to accept I was never going to get back to F1. One big problem was that the muscle down the front of my left thigh was fused to the bone and I couldn’t bend my leg. The cockpits were much smaller then, and you had to be able to get out of the car, from being fully belted in, in five seconds. I’ve had a lot of operations since, the most recent one only last March. I took out medical insurance when I got to F1, went to what I could reasonably afford without leaving myself skint. I had a £200,000 payout in the event of an accident and £200,000 medical costs, which back then was all right. But with the hospitals, Willi Dungl’s clinic and everything else, all that money got spent. The last two operations have been paid for by the BRDC.

“I had to earn a living, and I had no qualifications because I’d given up university to go racing. But my racing life had been an education, so I decided to put all that to good use. In 1992 I set up Martin Donnelly Racing. We kicked off in Formula Vauxhall Lotus, and we went into F3 in 1996. Our best achievement was winning at the British GP meeting against Jackie Stewart’s team. But I soon realised there were five big teams giving away subsidised deals, and they got the real talent, and the drivers that were left were the weekend warriors. Drivers would say, ‘The money’s coming through next week,’ so you’d get into your own back pocket, and then the money never came. MDR closed in 2004. Most of my work is for Lotus now, helping them with projects like developing the Evora. I drove Mario Andretti’s F1 car at the Classic Team Lotus day at Snetterton. I’ve got the Donnelly Track Academy, and I race one of the Lotus Elises from time to time. I did a race a few weeks ago for Ginetta. And I’m involved in coaching an 18-year-old Spanish boy, Ramon Piñeiro, who’s going really well now in Formula Palmer Audi.

“I don’t live in a big flashy house, I don’t drive a big flashy car. I’m just happy I can put food on the table for the family. Diane and I aren’t together now, but we’re still on good terms. We’re both happily married again, and she lives nearby. My oldest boy, Stefan, is 17, he wants university, a car, all those things, and somehow by hook or by crook we’ll get to it. Julie and I have two children, Charlotte is eight and Owen is five.

“I don’t feel bitter at all now about what happened. At first I did feel bitter, big time. When you’re in F1 you’re treated like a king, free cars, free clothes, free everything. You don’t have to go to work. Racing cars isn’t work, you’re just being paid a pile of money to enjoy yourself. I had my three-year deal with Lotus, everything was moving well, and then somebody switched off the light. One moment the light is on, illuminating the room, and the next moment it’s off. Everything you want to achieve is taken from you. It’s hard to deal with. I wouldn’t say I got depressed, because I’m not that sort of person, but there were times, through all the operations, when I did get low. I caught MRSA during one of my spells in hospital – that took a long time to kick. But motor racing is dangerous. It’s down to you. No one puts a gun to your head and says, ‘You’ve got to drive that car today’.

“I’ve been back to Jerez. An Italian magazine journalist took me out to where I had the accident, pointed to the place where I hit the barrier, but it meant nothing. I look at the pictures, I know those are my overalls, so it must have been me. But it doesn’t say anything to me.

“Ayrton Senna’s death, May 1 1994, did say something. When I first came to Norfolk he’d just joined Lotus, and he had a flat in Norwich. I knew him pretty well. I could never have aspired to the level that Ayrton reached, because he brought a new dimension to Formula 1. When he had his accident it was a massive reality check. Ayrton was World Champion three times over, he had his millions, his businesses all built up behind him. But he had no family, no son, no daughter to leave behind. I’ve got a fantastic family, and I’m content. I’ve learned that there’s more to life than racing cars.”