When you see it, what strikes first is the colour. Some 39 GTOs were made in two different body configurations and by no means were all in red. But to see this one in its pale green BRP livery, complete with Innes Ireland’s tartan strip across the bonnet, is to put its identity beyond doubt.

The focus of its restoration was not to make it ‘as new’. On the contrary, the brief handed down to Neil Twyman was to return it to its original state and, as Gregory confirmed to me, “competition Ferraris didn’t come out of the factory in showroom condition; they were racing cars and distinctly rough around the edges”. This is why there is next to no trim in the cockpit, with its tubular spaceframe exposed in places. It has one black windscreen wiper and one that’s silver – because that’s how it raced in period. Even the external bonnet catches that are so distinctive on other GTOs are nowhere to be seen, because the car never had them when new. And its original nose, which was replaced many years ago, has been refitted.

History recalls that 3505GT’s first outing was indeed to have been in the Sussex Trophy at the Easter meeting at Goodwood in 1962, but with Moss in a coma and Ireland already paired up with a UDT-Laystall Lotus 19 (with which he duly won the race), the Ferrari sat on the sidelines. Understandably Gregory’s thoughts were for Stirling in his hospital bed, not the GTO in the paddock. “I’d flown down to Goodwood for that meeting but had to get someone else to take the plane back. I was in no fit state at all.”

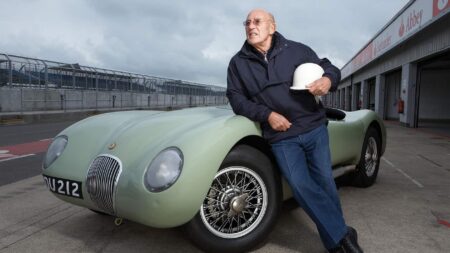

‘35050GT’ is back at the track where it had its finest hour

M Howell

Instead it made its race debut at the International Trophy meeting at Silverstone in May, where The Kansas City Flash, also known as Masten Gregory (clearly no relation), came home second. Its first win arrived later that month at Brands with Innes at the helm, so hopes were high for Le Mans where these two lead BRP drivers were to share the GTO. “It all started just fine,” recalls Ken Gregory, “with Masten and Innes driving beautifully.” But it was not to last: 11 hours in the dynamo failed and, with a rapidly dwindling supply of sparks and lights, the GTO was retired. Clearly it’s a defeat that rankles Gregory to this day. Despite the fact that there were no fewer than six GTOs in the race he does not hesitate to point out that it was his GTO that was leading them all (and the class) at the time of its retirement. Racing is full of what ifs, but it’s perhaps worth mentioning now that the GTO that inherited that lead not only duly won the class but overall was beaten to the top step of the podium only by a works Ferrari prototype.

How appropriate, then, that in all these circumstances its day in the sun would finally come and that it would be at Goodwood with Ireland at the wheel. Surprisingly he makes no mention of the 1962 Tourist Trophy in his autobiography All Arms and Elbows (and if you haven’t read it, you must) other than to say, “I also won a race or two in the new GTO Ferrari”. But the fact remains it was an epic encounter.

This time there were five GTOs in the race, four of them locking out the business end of the grid. On pole sat Ireland and 3505GT with John Surtees (in his first race in a Ferrari), Mike Parkes and Graham Hill mere tenths behind. To give some idea of the GTO’s superiority, Jim Clark’s Zagato Aston DB4 GT qualified in seventh place, three full seconds off Ireland’s pace, with Mike Salmon’s Zagato next, a further three seconds behind Clark. The question was not whether a GTO would win, but which one.