In 2009 it is difficult to comprehend – even though F1 racing was very much a minority interest then, with none of the TV and media coverage of today – how huge a presence Stirling Moss was in the national consciousness. He was one of Britain’s most famous men, and the whole country was galvanised by his accident and hungry for news of his condition. Unlike today, with 24-hour news channels and hourly bulletins on every radio station, back then the BBC Home Service only broadcast the news four times a day. The only exceptions were emergency announcements in time of war, or when the King was dying. Yet I clearly remember, as one of millions horrified by the injuries suffered by the world’s greatest racing driver, that Stirling was treated like royalty. In the days immediately after the accident, when most expected him to die, the BBC ran hourly radio bulletins on his condition.

As he regained full consciousness his will to recover, which had worked miracles after his 1960 Spa accident, began to assert itself. “When I started to come round I knew I’d had an accident, but I didn’t know where or when. Then I realised the left side of me was paralysed, so I started to focus on the bits I couldn’t move. It gave me something to work on. Eventually I started to get a slight movement in one finger of my left hand, so I concentrated on that, then I moved on to the other fingers, and then the whole hand. Lying there, I assumed absolutely that I would get back to racing. I reckoned I’d had much worse accidents – breaking my back and my legs at Spa, I came back pretty quickly after that. So I just thought, I’ve got to get on with this. But gradually it dawned on me that it was much more serious than I’d realised.”

On July 20, nearly 13 weeks after the accident, he left the Atkinson Morley, greeted by a huge press posse outside the hospital. Hobbling on crutches, he took the 11 nurses who had looked after him out to dinner, and gave each of them a small gift. “I went to Nassau to recuperate. But I was still in a bit of a state. I couldn’t remember anything, and my body temperature was different one side to the other. One cold hand, one hot hand. My speech was slurred, so people thought I was drunk. And I had no concentration. To open a door I had to think, consciously, ‘Put your hand on the knob. Now turn it.’ But the press gave me no peace. There were even paparazzi on the roof of the hotel in Nassau, with long lenses. Everybody was asking, ‘When are you coming back? Are you going to race again?’ The papers kept running stories about it. There was a lot of pressure on me to make up my mind. I knew I had to get the decision out of the way.”

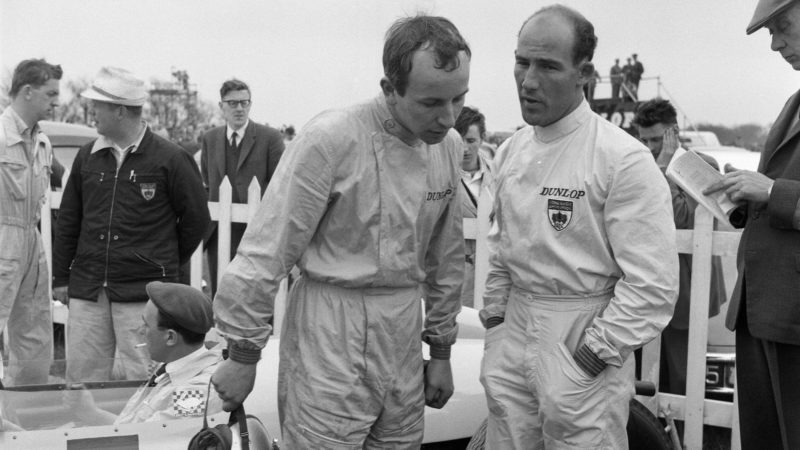

So just over a year after the crash, on May 1 1963, a damp, grey day, Stirling drove a Lotus 19 sports car around an empty Goodwood. As he went through St Mary’s no memories of the accident came back. He drove at proper racing speeds – at one point he spun coming out of the chicane – and his times in the conditions were competitive. But as he got out of the car he knew his decision was made.

“My times were quite reasonable, I was on the pace. But I found that I had to do everything in the car consciously. I’d approach a corner and think, ‘I’ve got to get over to the edge of the road here, I’d better brake now, this is where I should get back on the power.’ It all had to be worked out, nothing was automatic any more. Before, I could always jump in a car on any circuit, and get straight down to within a fraction of my best time. Then, if I wanted to put in a quick one, if I was going for pole, I’d work at coming off the brakes a little earlier, getting back on the power a little earlier. But I couldn’t do that in the same way, it was all a conscious effort. I no longer had the capability I’d had before. That was it. It was a depressing decision to have to take, but it was a very easy decision, because it was obvious to me that I wasn’t what I had been. If I couldn’t come back at the top, there was no point. I didn’t want to come back as second-best, my pride wouldn’t let me. That same evening, back in London, I announced my retirement.

Moss took all 11 nurses who looked after him whilst he was in a coma out for dinner after being discharged

Keystone/Getty Images

“In the years after that I sometimes wondered if I took the decision too early. If I’d waited two or three years I think my faculties would have come back, my concentration and my focus. By then Jim Clark had established himself as the best, and he might have been really tough to beat. When I raced against him he hadn’t reached his maturity: when I beat him, he was no faster than Innes [Ireland], but he got much faster than Innes later. But once I’d said I was out, I was out. If people retire, and then change their minds and come back, well, I don’t like that sort of thing.

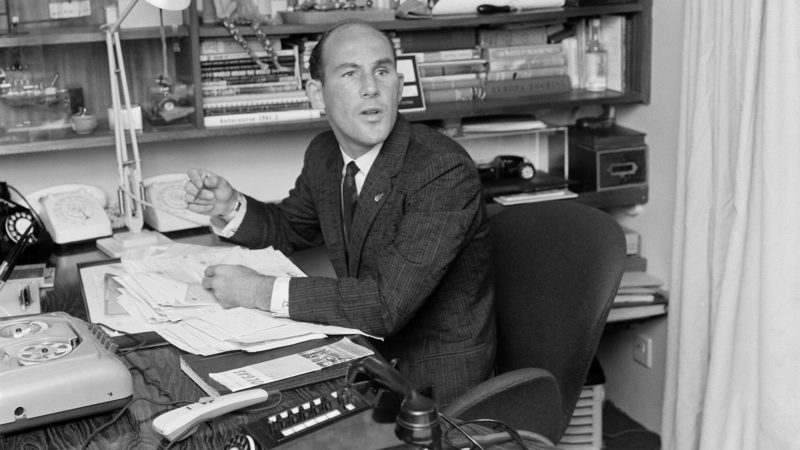

“For years I’d been well paid by the standards of the day. Because I was busy racing every weekend, I didn’t go out and spend money much, apart from chasing crumpet. But I hadn’t salted much away. In my last full year, 1961, I grossed £32,700. Out of that I paid all my own expenses, hotels, flights – I always flew economy – and after expenses I paid tax on £8000. I suppose that was roughly what a good lawyer would have earned in those days. But you paid very high tax rates then, so I probably netted about £3200.