Lunch with... Richard Attwood

This English gentleman upset his father by racing for longer than he was supposed to, but success at Monaco and Le Mans in particular made it all worthwhile

James Mitchell

Richard Attwood could never be anything but English. Scion of a prosperous Midlands family with links to the motor car that go back three generations, he was educated at Harrow, and served his apprenticeship at Jaguar in the British Racing Green days of Lofty England. His courteous, relaxed demeanour, his good manners, and his faintly sardonic sense of humour are all definitely old school. And every one of his Formula 1 races was in British machinery — BRM and Lotus.

Yet his finest hour came at the wheel of a German car, scoring Porsche’s first-ever win at Le Mans in 1970 with the fearsome 917. His brilliant works Grand Prix debut at Monaco in 1968, when his BRM finished second to Graham Hill’s Lotus 49, has ensured his place in the F1 record books. But, in a professional career that lasted only seven seasons, he was most in demand as a long-distance sports car driver: one who could always be trusted to combine competitive speed with smooth finesse and a willingness to look after his machinery.

We meet at The Old Vicarage at Worfield, an excellent restaurant not far from Richard’s home on the Shropshire/Staffordshire borders. He chooses asparagus panna cotta and halibut.

“The family firm in Wolverhampton had agencies for Rolls, Bentley, Aston Martin, Daimler, Vauxhall and Standard-Triumph, so I grew up in a motoring atmosphere. My father raced a bit at Brooklands, so it was unfinished business for him, and at first he was keener on my going racing than I was. My first car at 17 was a Standard 10, and I did a race at Goodwood in it, if you can imagine that. Then I got a Triumph TR3A and did a year of club racing. It was totally standard, up against cars with Webers and glassfibre panels, but I did win a race at Oulton Park when it was wet. For 1961 I wanted to modify the TR to make it competitive, but my father said, ‘Don’t bother with that. You want a single-seater. We’ll get one of those Formula Juniors.’ I didn’t really know what he was talking about, but he saw it was the way to go. Without him I wouldn’t have done a damn thing.

“He got me a Cooper, probably because it was available. A handful of other locals were doing FJ — Bill Bradley, Jeremy Cottrell, David Baker and Alan Evans, who ran a car for John Rhodes — so we called ourselves the Midland Racing Partnership. But each of us owned his own car and employed his own mechanic. At the time I was doing my Jaguar apprenticeship. Having been competitions manager there, Lofty was now assistant managing director. He kept a close eye on all the apprentices, and he rather liked it if one or two of them went racing. Sometimes when I was meant to be at work and wasn’t, because of my racing, I’d find I had been magically clocked in.”

During 1962 Richard ventured to Monaco, and immediately got himself noticed in the Formula Junior race supporting the Grand Prix. His privateer Cooper finished second in its heat to Peter Arundell’s works Lotus, and in the final he was running second to Arundell when the engine failed. Monaco was to run like a thread through his single-seater career.

“We knew MRP was never going to get much recognition unless we ran as a works team, so for 1963 we pooled our resources. David Baker negotiated a deal with Eric Broadley to buy three Lola Juniors at a big discount and run them for Bill Bradley, David Hobbs and me. And I won the Monaco FJ race. That really put me on the map, because people realised I hadn’t got the best car, or the best engine.” He had to get past the Brabhams of Frank Gardner and Jo Schlesser to do it, but his smooth, accurate pace around Monaco proved unbeatable.

But at Albi in September, battling with Peter Revson, he crashed, breaking a leg. With typical honesty he blamed himself. “I was focusing on the back of Peter’s car instead of the track, and I ran wide on a fast right-hander. I reckon it took me my first four years in racing to learn completely the art of total concentration.”

Meanwhile Richard had had his introduction to Le Mans. “Eric Broadley had just done his Lola GT, which I think was an absolutely iconic car, more so than the GT40 itself. It was so small, so cute, and for its time so clever.

“Le Mans was very last-minute. Two Lolas were entered for John Mecom’s team, but when Mecom realised the cars were unlikely to be ready he pulled out. But Eric was still determined to run. So he called on his FJ drivers, Attwood and Hobbs, because they were going to cost him virtually nothing. There was a frantic struggle to get the car finished in time. It was driven down by Eric, with a mechanic in the passenger seat with his toolbox on his knees. They worked on it on the ferry, and I think it broke down a couple of times on the way through France.

“The final straw was that, although the Lola had wing mirrors, the scrutineers said it had to have an effective inside mirror, and that just gave you a view of the air intake to the carburettor. Eric had been without sleep for days and he was ready to throw in the towel, but Peter Jackson of Specialised Mouldings was there and they hacked away at this lovely car until the scrutineers let it through. We went well in the race, but we had gear selection problems — dirt got into the cable-operated mechanism going down the centre of the car. We managed to cope with it until, early on Sunday morning, David arrived at the Esses in neutral and crashed.”

Attwood works his magic at Monaco in 1968 in a ageing BRM

Motorsport Images

At the end of 1963 Richard earned the premier Grovewood Award as Britain’s most promising young driver. Through his Lola contacts there was a well-paid Ford sports car contract in the offing, and BRM had been in touch too. “That was when my father said, ‘Right, lad, you’ve had a good time, you’ve earned your colours. Now you can come back into the business.’ He was an autocrat, and he expected me to say, OK Dad. But my prospects in racing were looking good, so I decided to keep at it for a while longer. It soured our relationship, and when I did stop racing and joined him in the early 1970s he never gave me any real authority. He was still working when he died in 1981, and in order to distribute the family shareholdings the whole business was sold. It was very sad.

“When I got the Grovewood Award, Raymond Mays offered me a BRM test contract. I did hardly any testing, but they did let me drive in the Easter Monday Goodwood race. There were a lot of retirements, and I finished fourth. As it was a Monday [BRM owner] Sir Alfred Owen was there — he never went to Sunday races because of his religious beliefs — and afterwards he shook my hand and said, ‘You drove a great race. Would you like to do some more?’ But it was the only race I did. I practised the four-wheel-drive BRM for the British Grand Prix, but 4WD never worked even with 3-litre F1 cars, so it didn’t have a hope with the 1500cc F1.

“The first race of my Ford contract was in a Shelby Cobra in the Nürburgring 1000 Kms, driving with Jo Schlesser. A Cobra round the bumpy old Nürburgring — it was a ridiculous car. All the Cobras crashed or fell to pieces, and we had various stops to repair things that had broken. Eventually Carroll Shelby said to me, ‘Please, just finish.’ We did, in 23rd place behind a couple of Abarths — but we won the class and earned Ford the points.

“Jo Schlesser was a wonderful guy, very funny. He made jokes about everybody and everything, and could take off all the important people in motor sport. He was like the Graham Hill of French motor sport. His death at Rouen in the air-cooled Honda in 1968 should never have happened. That car was totally unsorted and I’m sure he was out of his depth. But as a Frenchman he wanted to drive it in the French Grand Prix.

Lola supplied cars to Midland Racing Partnership for F2

Motorsport Images

“At Le Mans I had my first race in a Ford GT, again with Jo. I was flat out on the Mulsanne Straight when I saw flames in my mirror. I kept the throttle fully open in case it sucked the flames back in and put the fire out, but that didn’t work, so I stopped by the signalling pits and got out. I thought I ought to do something, and I’d just started to open the bonnet catches when there was a whoof and I thought, ‘Maybe I’ll leave it’. So I stood by and watched it burn.”

For 1964 MRP had been promised a monocoque Lola for the new 1-litre Formula 2, but until it was ready the old FJ Lolas were converted to F2 spec. In the space of four weeks Richard was second to Jim Clark at Pau and again at the Nürburgring, and won at Aspern. But as other new F2 cars came on stream the Lola became progressively less competitive. When the monocoque car finally arrived, well into the 1965 season, Attwood and his South African MRP team-mate Tony Maggs finished 1-2 in the Rome Grand Prix at Vallelunga, beating F2 king Jochen Rindt into third place.

“Formula 2 was a wonderful system to teach the younger drivers how to run with the established guys, because most of the F1 stars did F2 too. You knew everybody and it was very friendly. In fact, MRP had a little Christmas party in a pub in Wolverhampton, and just for fun we invited Jim Clark and Graham Hill. We never thought they’d come — but they both did! Imagine that happening today with Lewis Hamilton and Jenson Button. Actually Jim Clark’s long-time girlfriend Sally Stokes was originally from Wolverhampton: it may well be that Jimmy met her at our party.

“Tony Maggs was one of the two nicest people I met in motor racing. Lucien Bianchi was the other. In 1965 Tony had an accident during a race at Pietermaritzburg. Something broke on the car, and a child watching in a prohibited area was killed by the wreckage. Tony was distraught, and decided to retire there and then. He’d been driving in sports car races with David Piper, and he suggested me as a replacement. One of the first races I did for Pipes was in his old 275LM in the Reims 12 Hours, with Lucien as co-driver. The car was absolutely singing. Lucien was the ideal co-driver: as fast as me, always looked after the car, and you knew if anything was going to go wrong it wouldn’t be his fault. I was really cut up when he was killed at the Le Mans test weekend in 1969.

“At the end of 1964 I told Ray Mays my contract with BRM was a waste of time: I’d done one F1 race and not much testing. He didn’t want to let me go, so he came up with a proposal to lend a works-spec BRM V8 engine to Tim Parnell for one his Lotus 25s so I could go F1 racing. Well, for someone who’d barely done F1 that sounded pretty good. The other driver in the Parnell team was Mike Hailwood, about whom I knew nothing except that he was a bike man.

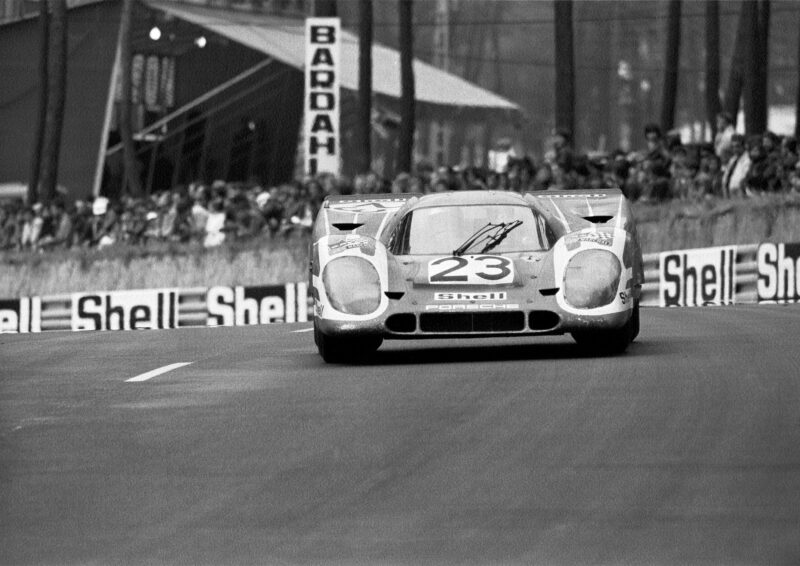

Scoring a historic Le Mans win for Porsche in 1970 aboard the 917

Motorsport Images

“I went down to the Parnell place at Hounslow to sit in the car before it went off to the first round at Monaco. It had the usual little tape labels under the switches to say Fuel Pump and Ignition and so on. But by the gear lever there was a label saying Gear Lever, and on the steering wheel there was a label saying Steering Wheel. That was Mike taking the piss. I was coming in with a works BRM engine, and he had the bog standard engine and was paying for his drive. He probably thought I was a jammy rich bastard and a public school poof.

“We got to Monaco and he was very off-hand with me. We both retired in the race, but we went to the prize-giving and started getting a few down us, and we just hit it off. We were still going at 5.30am, by now with a couple of girls. Mike always liked the ladies. Turned out he was born two days before me, and his upbringing was very similar to mine, so we had a lot in common. He was such a talented racer: as well as being the best on two wheels, he definitely had enough ability to make it to the top on four. He was multi-talented: he could pick up any musical instrument and play it, he mastered water skiing straight away, he always seemed to be able to do anything. We were close friends for the rest of his life. One evening in 1981 he went out in his Rover with his two young children to collect some fish and chips, and a truck did an illegal U-turn in front of him. Mike and his daughter were killed, his son survived. The truck driver was fined £100.

“I did eight championship Grands Prix with the Parnell Lotus-BRM, but it was never competitive. At Spa in the rain I had a big off. I was just trying too hard in a car that was three years old. On the Masta Straight I hit a river of water running across the road, went sideways for about 400 metres and then hit a telegraph pole. The pole stoved in the monocoque and wedged me into the cockpit, and I’d hit it with my head, but fortunately I was conscious. But I couldn’t get out of the car, I couldn’t move.

“There were no marshals, nobody around except a couple of spectators watching the race in the rain. I gesticulated to them frantically and they came over and lifted the car away from the pole, but the front of the car had collapsed around my feet, which were totally jammed beyond the remains of the pedals. I wriggled and strained but I just couldn’t get out. Then, whoof, the car went on fire, and suddenly, somehow, I’d got myself out of it. I was burned a bit — we had those two-piece Les Leston overalls then, and the fire got me around the join. The car burned for 20 minutes. With nobody around, I would have died quite quickly.

“Colonel Ronnie Hoare, who ran Maranello Concessionaires, the British Ferrari agents, was an old fashioned chap, a sort of unconscious snob. I’d done Le Mans with Piper in his P2 in 1966, but for the ’67 race he thought he had the perfect team, me and Piers Courage, because Piers had gone to Eton and I’d gone to Harrow. I always had a stripe in the Harrow colours painted down my helmet, so Piers decided he might as well do the same with the Eton colours. Piers was just a lovely man. We drove down to Le Mans in his Porsche 911T and I still remember that induction roar from the carburettors, so much better than fuel injection. In the race the Colonel’s P3/4 lasted 15 hours before the oil pump went. I finally finished Le Mans for the first time in 1968, seventh place with David Piper in his trusty green 275LM — he’s still got that car, and he’s still racing it.

In the fast but unreliable Alan Mann Ford F3L during the 1968 Nurburgring 1000km

Motorsport Images

“Also in 1968 I drove the Ford F3L sports car for Alan Mann. I know Frank Gardner didn’t like the F3L, but with that DFV engine it was a dynamic car, way ahead of its time. The day Chris Irwin had his accident at the Nürburgring, Frank and I were paired in the other one. Alan Mann says to this day there were bits of a rabbit embedded in the front of Irwin’s car which might have caused the accident, but I just think Chris got into this fantastic thing and started driving it like a Formula 2 car, and you couldn’t do that. Frank and I knew the score, we were going to bring it home. But on the first lap I was coming down to Adenau Bridge and I heard clunkety-clunk underneath the car. David Hobbs was following me in a JW GT40 and he saw something bouncing past him. For some reason I guessed what it was: the brake pads on the right front had fallen out. I nursed the car back to the pits without touching the brake pedal — fortunately there was so much torque reversal with the DFV you could use the engine braking — and I got new pads fitted and was off again. But it was in vain: later on the electrics died.

“I’m not saying the F3L was easy to drive, but it was so fast you could make time to nurse it through the corners. I put it on pole for the Tourist Trophy at Oulton Park, and I was 10 seconds in the lead on lap 10 when the differential failed. Funnily enough, David Piper had nominated me as reserve driver for his Ferrari that day, so when the F3L stopped I took over the Ferrari and finished second, about 10 seconds behind Denny Hulme’s Lola T70.

“I’d done no more F1 apart from a drive in a Cooper-Maserati in the Canadian GP in 1967. I’d been doing a lot of tyre testing for Coopers at Goodwood, so that was a sort of thank you. Then in May 1968 Mike Spence, who was in the BRM F1 team with Pedro Rodriguez, was killed at Indianapolis. I knew him better than most. His wife Lyn was the sister of Tony Maggs’ wife Gail, and I’d spent a lot of time with them all.

“I got the call on the Tuesday before Monaco. I think it was Tony Rudd who rang me. At Nice Airport I bumped into Louis Stanley, who was married to Alfred Owen’s sister and reckoned he held great sway over the BRM team. ‘What are you doing here?’ he said. I replied, ‘I’ve come to drive your car in the Monaco Grand Prix.’ He was absolutely incensed, because he hadn’t been told. I guess he didn’t think I was good enough to drive the car. The works BRMs were meant to be numbered four and five, but Pedro had No 4 and I was No 15, along with Piers at No 16 in the Parnell BRM. That was a Stanley snub, because he didn’t want people to think I was a works driver.

“Pedro had the new P133, I was in the old P126, but I qualified sixth and he qualified ninth. Monaco was very bumpy then, so I worked away with [BRM mechanic] Alan ‘Dobbin’ Challis and softened my car up, put the tyre pressures right down and got it handling howl wanted. I was second by lap 17, and by the end of the 80-lap race I was 2.2 seconds behind Graham Hill’s Lotus 49. On the last lap he was already waving to the crowd, and he caught sight of me out of the corner of his eye at one of the hairpins and had to get going again. He’d paced the whole race, winning at the lowest possible speed like you should, but he was a bit pissed off not to get fastest lap.” Richard’s 1min 28.1sec in the old BRM was a new lap record.

It was a storybook drive for a stand-in driver, and he was duly retained as BRM No2. “But Monaco had disguised the power disadvantage of the old BRM V12 against the DFVs. As the season went on the car got less and less competitive, despite various development tweaks, different nose shapes and so on. Louis Stanley decreed there was nothing wrong with the car and it was all the drivers’ fault. So he fired me and put Bobby Unser in the car, because he’d won Indianapolis that year. Shows the brain the man had. Unser did one race, qualified 19th, blew up two engines and crashed. Not a very good choice. Louis Stanley was a buffoon.

“But I did do Monaco the next year, for Lotus as a one-off. The rear wings had fallen off Hill’s and Rindt’s 49s at Barcelona, and Jochen was hurt, so I suppose Colin Chapman thought, that Attwood seems to be quite good at Monaco, better get him in the car. That’s when I realised how bad the BRM had been. The 49 was a racing car, it was alive, made the BRM feel like a lumbering old thing. And the power of the DFV was like an electric shock in comparison.

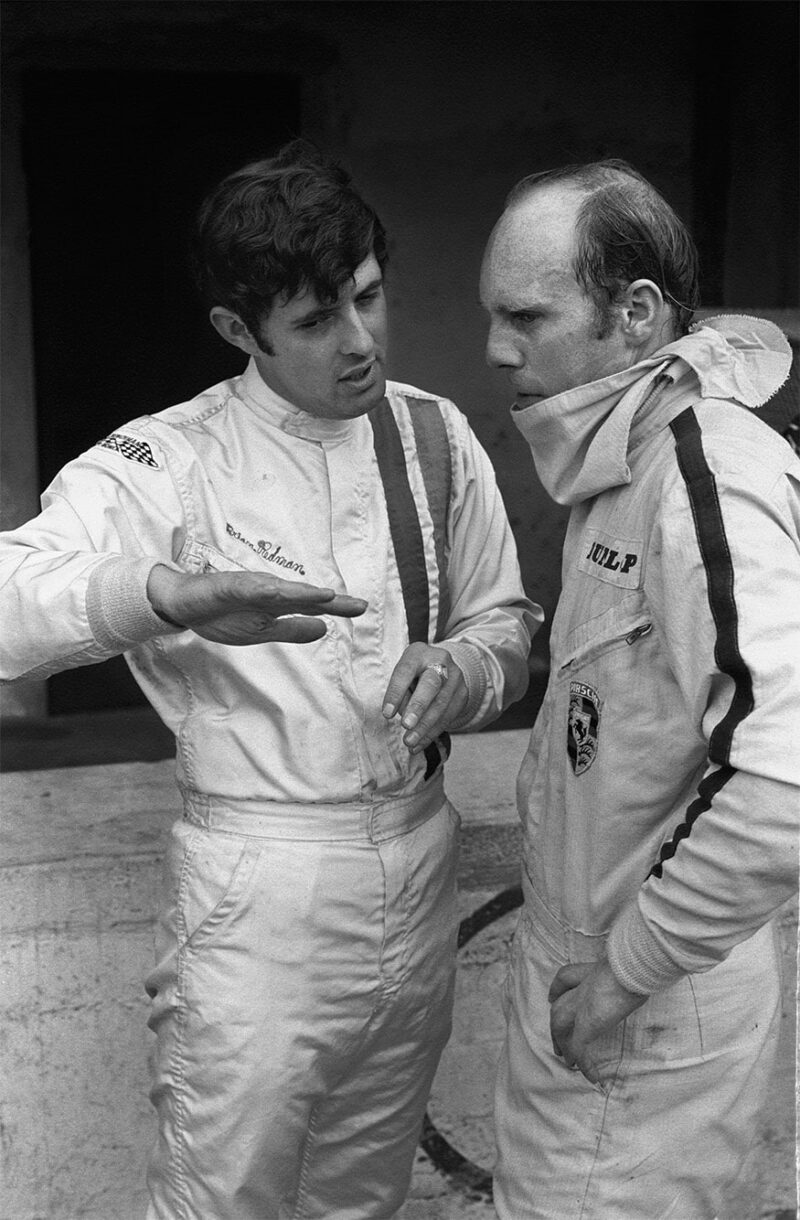

Discussing 917 handling with Brian Redman

Motorsport Images

“During the race the gear knob fell off and was rolling about in the cockpit. I thought I’d better retrieve it in case it got jammed up with the pedals, and also the thread on the gearlever was shredding my hand. It took several laps. I could only reach it under hard acceleration, when it rolled back towards the seat. Finally I managed to grab it and screwed it back on again. I finished fourth. I also did the German Grand Prix that year in an F2 car: Frank Williams’ Brabham BT30. Frank didn’t really want to run it, but the organisers paid him some serious cash, and he paid me quite well. I finished sixth overall, although I wasn’t allowed to claim championship points.

“For 1969 I had two good sports car offers. John Wyer wanted me in his team of Gulf GT40s: we’d always got on well, and I was going to be paired with Hailwood, which would have been huge fun. But Porsche was embarking on a massive programme. I was really torn. The money was more or less the same, but the GT40 was basically six years old, and I knew Porsche was the future, so I took that.

“I was second with Vic Elford in the BOAC 500 in the 3-litre 908, but by then Porsche had come up with the big flat-12 917. As everybody knows, in its early unsorted form it was just dreadful, but Vic was desperate to drive it at Le Mans. And he asked for me as his co-driver. I could have killed him. In the race the car needed refuelling every 50 minutes, and we did double stints from the start. It had four exhausts, two out the back, one under each side, level with your ears. I was deaf and had a blinding headache for the entire race. My neck ached because the thing was so fast, nothing at Le Mans had ever had that sort of power, and I had to drive resting my head against the rear bulkhead. On the Mulsanne Straight it was wandering about all over the place, airborne at the back, then airborne at the front. When you got to the Kink you had to come off the throttle to get it back down on the ground, then you had to turn the steering a bit to get it to lean on its outside tyres. It was a nightmare. In the night we did triple stints, two and a half hours, to give each other some rest time. I was drained.

“With 20 of the 24 hours done, we were leading by six laps. Then the gearbox broke. We knew it was coming: it was getting more and more difficult to get gears. The casing had cracked and the gearbox was sagging down, and it was leaking oil as well. But I didn’t feel disappointed. I couldn’t have cared less. I was just delighted to get out of the car.

“In the debrief we told the factory the aerodynamics were all wrong, but they didn’t believe us. They changed everything else on the car, but they didn’t change the shape. Brian Redman tested the car and told John Horsman of JW it was just as bad, and John said, ‘Let’s take off the tail section.’ Brian went out with the back end of the car naked, and immediately it was better. That’s when they finally got the message.

“Next February Porsche rang and said, ‘Herr Attwood, what configuration do you want for Le Mans this year?’ They had the new 5-litre engine by then, but I asked for the 4.5 because I thought it would be less strain on the transmission, and short-tail bodywork because I reckoned it would be more predictable. My choice of co-driver was Hans Herrmann. I didn’t speak German and Hans didn’t speak English, so we had to communicate in sign language, but that was fine. At Le Mans you didn’t want the fastest co-driver, you wanted somebody who was reliable, and I knew he was that. What I didn’t realise was how much he wanted to win Le Mans, having lost it by a few feet the year before in the closest finish ever.

“That year it rained a hell of a lot. Choosing the 4.5-litre engine was a mistake, because the 5-litre had so much more torque. We only had a four-speed gearbox instead of the five-speeder on the 1969 car. And we weren’t allowed to use first gear for the two slow corners, Mulsanne and Arnage, only for getting out of the pits, because they didn’t want us to strain the transmission. We had to go from 25mph to 230mph using three gears, and we were losing 6sec a lap to the 5-litre cars. I knew we hadn’t a chance — but we won. Well, we didn’t so much win as everybody else lost.” Six of the eight 917s retired, and nine of the 11 Ferrari 512s. The Attwood/Herrmann 917 was in the lead by 2am, and stayed in front for 14 hours to the flag.

What Richard forgot to mention, until I reminded him, was that he was very unwell that year. “Oh, yes. Sore throat, swollen glands, and I couldn’t eat or drink anything because I couldn’t swallow. All I had throughout the race was some milk. Afterwards I couldn’t face the victory celebrations and crawled away to bed. I got home and saw the quack, and he found I had mumps.

“That year Steve McQueen was making his movie Le Mans. I was hired to work on it for $150 a day, although we got double when the shooting involved something dangerous, like nudging another car to move a lever that triggered an onboard camera to pan as you went by. I was in a 917, doubling for Steve, and Mike Parkes doubled for the Ferrari actor in a 512. We were still there in November. They changed scriptwriters, they changed directors, it all went hugely over schedule and over budget, and it was all a bit of a lash-up.

“Early on we were all having a bit of a lairy go for the cameras, out of Mulsanne and up the straight towards Arnage, and Steve in another of the 917s was keeping up with us — until he missed a gear and blew the engine. The only available replacement was a brand new one from Porsche at huge dollars, so the film company made an insurance claim. The insurers asked how it had happened and found out that Steve had been driving. They didn’t realise the star was actually doing the stunts, and of course if he’d been injured the film would have been scuppered. So he wasn’t allowed to drive any more. He was really upset about that.

“Parkes and I used to eat with Steve in that restaurant in the trees off the Mulsanne Straight. He didn’t want to talk about movies, just about racing. He was a genuine, knowledgeable racing buff. He respected us because of what we did, and we respected him because he could make huge money and we couldn’t. He liked kippers, so I brought him some from England. He also asked me to find him a JAP-engined Morgan three-wheeler. He ended up with a couple of them, I think. Great fellow, but very American, of course. Different language to us.

“When we did those shots with the 917s and the 512s it was at pretty much full racing speeds, so there was always a risk. You had to be on it from the moment you started, and with all the hanging about there was a concentration problem. When it was time for a shot and I got my helmet on I would get myself mentally fixed, like I was going into a race. One morning I was in the lead car, Mike Parkes was chasing me and David Piper was chasing him. We did our run up to White House, got to the end, and Mike said, ‘Where’s David?’ He’d gone off on the left, the barrier had folded back and he went straight over it. The car disintegrated, with him still strapped into the cockpit. He was flown straight back to England, but they couldn’t save his leg.

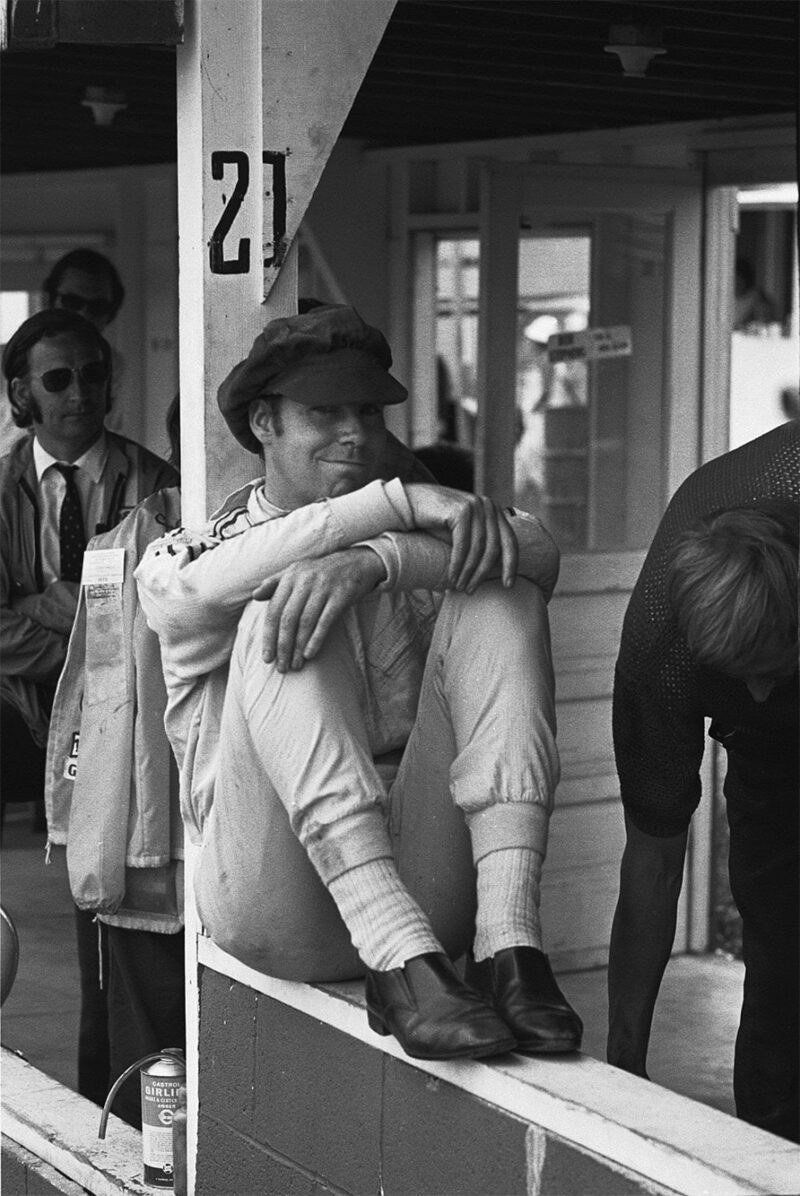

“In 1971 I did fewer races, weaning myself off it. I’d got married in 1969, my wife and I wanted kids, and I wasn’t going to have children until I’d stopped racing. Most drivers, when they stop, don’t have anything to do, but I had the family business to go to — not realising I’d left it seven or eight years too late for my father. But John Wyer asked me to drive a JW 917 at Le Mans, with Herbie Muller as my co-driver. I knew he was a wild boy, but I got him to understand what Le Mans was all about, and he did an impeccable job. We were leading at half-distance when a synchro cone fell off and the car jammed in gear. I got it back to the pits and it took them ages to sort it out. The Marko/van Lennep 917 had the same problem about three hours later, but by then they knew how to mend it and it took them half the time. So we were second.

Attwood only raced professionally for seven seasons before the family business beckoned

Motorsport Images

“My other sports car race that year was the Osterreichring 1000 Kms, but Pedro Rodriguez did almost the whole race. I just filled in. I’d driven with Pedro quite a lot: he was a funny little guy, but what a constitution he had. The race was 170 laps, and he did 157 of them. After he’d done three hours they brought him in, put me in the car, he had a pee and a drink, rested for a few minutes and then he said, ‘I’m ready to get back in now.’ So they brought me in, and he drove to the end. We won by two laps.

“I was only given about five laps of practice for that race. That year I wasn’t in a car every weekend, and if you’re slower than your team-mate you feel pressure, because you feel you’re going to let him down, or let your team down. You’re more likely to throw it off the track if you’re struggling to get up to the other bloke’s speed. And the old Zeltweg was a scary place. Past the pits and uphill through that adverse camber right, with the barrier on the left — no way could I take that flat in the 917. I said to Pedro, ‘You’ve got to help me on this. How do you take that corner flat? “Easy’, he said, ‘You just take eet flat.’ That was the only help I was going to get from him! Pedro had such faith in that car, he’d driven it such a lot, and he had it set up with the minimum of downforce to take that corner flat and still maintain the speed around the circuit. So when the IN board was shown I risked John Wyer’s wrath by staying out for another lap, and managed to get within a couple of seconds of Pedro’s time. Then I relaxed: I was happy with that.

“Then I retired. I divorced myself from motor racing completely and worked for my father — earning one sixth of what I’d been getting as a driver. But in 1984 Michael Salmon persuaded me to do Le Mans with him for the Aston Martin Nimrod team. It was a disaster. In the other car were Ray Mallock, who was very quick, and the American Drake Olson. At around 9pm John Sheldon was in our car: Michael and I had both done our first double stints and we were together in the pits, on a high because it was going really well. Suddenly everything went quiet. When that happens at Le Mans you know it’s something bad, but you don’t expect it to be your car. Sheldon had gone off at the Mulsanne kink. Very big accident, destroyed the car, caught fire. And this fellow Olson drove straight into the wreckage. Both Astons out in the same accident.”

Today, an energetic 68, Richard is much in demand as a historic racer. He has taken part in every Goodwood Revival, in others’ cars as well as his own BRM P261. Most weekdays he is working for Porsche, Ferrari or Audi, giving demonstrations and track-day tuition, and the day before our lunch he’d been lapping MIRA in an R8 with the Minister of Transport aboard. He has sold his own Porsche 917 after 22 years of ownership, but still has an Aston Martin DB2/4 in his garage. His professional career ended more than 35 years ago, but cars still play a major part in the life of this English gentleman. He’s evidently happy about that.