This place is full of busy. The B38 to Glenavy and B154 to Dundrod, divergent at this point, are pulsing arteries. And then some trotting rigs clip by: Ulster is nothing if not oddly juxtaposed. Which is why a 126mph lap record is deemed still acceptable here as the rest of the UK snuggles into its Nanny State way of life. Ireland has always been different: open minds to closed roads. It was even so in the days of Empire: the Gordon Bennett race of 1903 was based at Athy in the Republic, while the RAC TT was run at Ards, sited on the opposite side of Belfast to Dundrod, from 1928-36. Soon after the cessation of WWII, Ulster Automobile Club decided they wanted the TT back. For this they needed a new track. Dundrod was first mooted in ’47 and rumours firmed up when in ’48 Ulster AC cancelled their Trophy race on the Ballyclare circuit, stating that they preferred to wait until the new circuit was ready. By late ’48 the secret was out; JW Haughton, PB Webb and W Grigor, surveyor to Antrim County Council, were the movers and shakers, and the track was ready by 1950. That August saw Peter Whitehead’s Ferrari 125 win the Ulster Trophy at Dundrod, averaging 84.32mph over 111 miles to beat the ERA of Bob Gerard.

The following month the TT returned, and on 16 September, the eve of his 21st birthday, ‘wonder kid’ Stirling Moss came of age. He’d been in touch with the major manufacturers in a bid to land a sports car drive, to no avail. They knew he was quick, too quick for his own good perhaps, and politely declined. Tommy Wisdom knew better, took a calculated gamble (they were to go Dutch on any prize money) and offered Stirling the wheel of JIATK988, his aluminium-bodied XK120 – the car of every schoolboy’s dreams. Stirling had his arm off. He might have thought better of it, though, after setting a slow time in first practice. It was only a glitch, however. He was fastest the next day and led the race from the second lap to the last, averaging 75.15mph for 224.45 miles to win on the road and on a handicap. His feat the first of seven TT wins was made all the more meritorious because it tippled down throughout, the press tent falling (literally) victim to the accompanying howling wind. He’d shed his 500 specialist tag and nobody that day would have guessed his first GP victory would be still five years away.

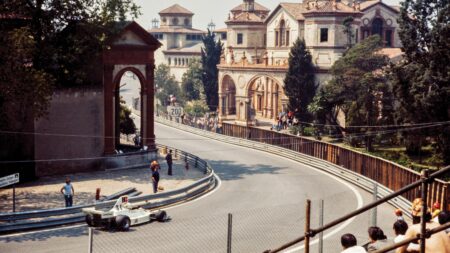

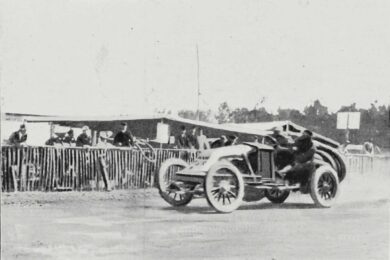

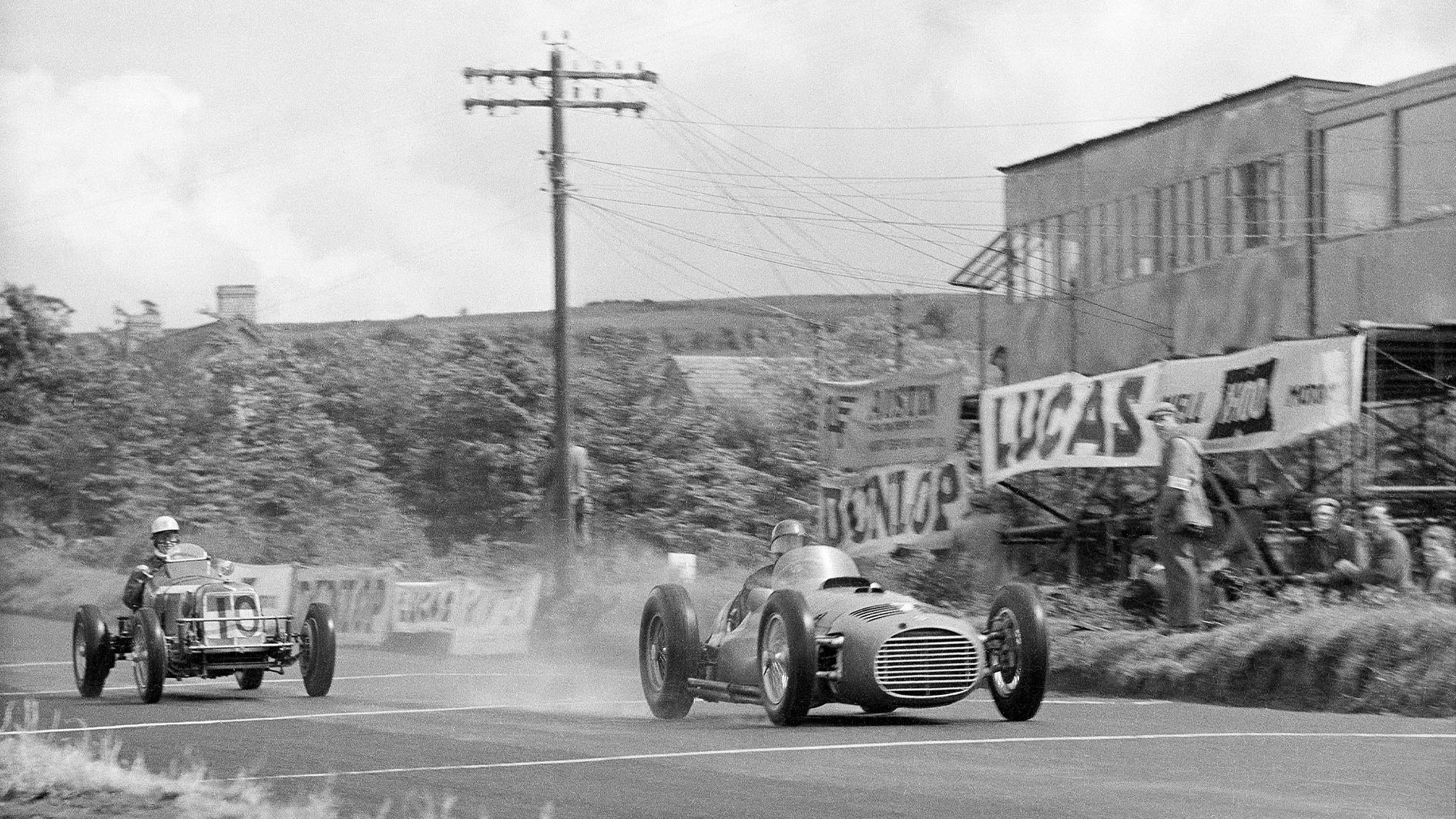

…and blasts past the ERA of Ron Flockhart

Getty Images

Moss won the TT again in 1951, dominating proceedings in the new C-type Jag, averaging 83.55mph to beat team-mate Peter Walker. He was upstaged that year, however, by the performance of world champion Dr Giuseppe Farina in June’s Ulster Trophy.

At the last minute his entry was changed from Maserati 4CLT to Alfa Romeo 159, a 400bhp device capable of almost 190mph a whole new ball game. He won, of course, and set a lap record of 4min 44sec (94mph) that was to stand for four years. But how much faster could he have gone had he been pressed harder?