I scored a few points, but as the season went on, I wasn’t very happy with my car. Every time they filled the fuel tank I had a strange sensation I felt I had less space, as if the chassis was bending. I noticed it again at Monza; I couldn’t drive the car in a straight line. I didn’t do much testing, but after I tried Nelson’s T-car at Silverstone, I was convinced there was something wrong with my chassis.

Because my place in the team wasn’t guaranteed — I had a race-by-race deal — I didn’t complain too loudly about the car. I knew Emanuele Pirro was pushing to get my seat.

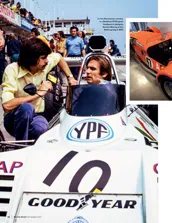

Charlie Whiting was my engineer, and he knew about the problem, but I think it was down to me to say something, so finally I told Gordon Murray. They said were going to make a new chassis for Nelson, and I’d have the T-car.

Brands was the first race with it, and suddenly, I was right there. I was fourth in first qualifying, but I had problems on Saturday so I started seventh. I felt very good in the car, and chose the harder tyres for the race, so I didn’t need to stop — we didn’t have refuelling in those days. I wanted to stay out and keep my rhythm.

With a new chassis underneath him, Surer was quick to battle at the front

Mike King/Allsport/Getty Images

I gained a place from Prost at the start, and on lap six Rosberg spun and Nelson hit him. Although it was Nelson I just thought, “OK, two out!” I didn’t care who it was, they were just two drivers who were difficult to pass.

In reality I only gained one place because Stefan Johansson passed me in the Ferrari. At the beginning I struggled because the tyres were too hard, but then it got better and I started passing cars. Stefan was no problem, and then I passed Elio de Angelis to go third. Then came Senna.