“He made only one goof the whole time and that was due to the pressure of racing at Trois Rivières. He took off from pole but the lights hadn’t changed and everybody else stood still. So he stops, sticks it in reverse and is backing up when the lights change and everyone else is going forward! He got going, came flying through the field, then flew into the wall. It was kind of funny. So I had these T-shirts made up with stop lights on them, red and green, and, at the next race, when he was at the drivers briefing I got the crew to put them on. When he saw them he just cracked up, all smiles. Then the green light comes on and no-one even saw which way he went. He damn near lapped the whole field.”

By this time Gilles had asked his manager and benefactor Gaston Parent to watch his kid brother to see if he could help. “I had long talks with Marlboro,” Parent recalls. “They were supporting a team in Italian F3 and were interested. We arranged a test at Monza, he came over and he did very, very well.”

Matthews enlarges on just how well Villeneuve went on a circuit he’d never seen, in a type of car he’d never driven: “The F3 lap record fell on his seventh lap. When he came in, Marlboro’s people were pushing the contract into the car. It was a good contract” A point which Parent confirms: “He would have been well paid and I’d fixed a deal with Giacobazzi. They were going to get him an flat in Modena, Agip were going to back him and we’d arranged a ship to bring his motorhome over. But the best part was that in year two the contract said he would be part of the Alfa-Romeo F1 team.”

Jacquo turned it down.

“He didn’t like Italy,” sighs Parent. “He didn’t like the ambience, didn’t like anything. They didn’t live the same as we do in Canada and he wasn’t ready to accept the displacement within that context. At night the eateries closed at 9pm which he didn’t like. They served him Parma ham and he was saying .look, they can’t even cook ham right’. He wasn’t interested. It was self-indulgent, I thought. It goes back to him racing to please himself, not to attain a goal. It’s a funny attitude and completely different to Gilles.” Mauro Baldi duly got the F3 drive and in due time was installed in the Alfa F1 team…

“I didn’t see why I needed to Europe to get to Formula One,” says Jacques simply. “Gilles didn’t”

Parent, exasperated, temporarily walked away. Jacques hooked back up with Shierson who was keen to attempt the Atlantic championship double. Villeneuve duly delivered, dominating the ’81 series. It was a season Shierson enjoyed immensely: ‘That was so satisfying. Everyone was real comfortable with each other and we went out there and smoked ‘ern again, and had a lot of fun doing it. Celine was a critical part of Jacques being happy there too. She’s a delightful person and she was an integral support mechanism for him. Just little things, which are so important for a driver’s well-being. He was a bit of a junk food junkie and she’d make him chips, make sure he was happy. He was very lucky there.”

According to Matthews, “The March we ran was definitely not as good as the Ralts most of the field had. Yet Jacques just won anyway. He was great to work with too. He’s got excellent feel for the car and gives great feedback. He can tell exactly what the revs are at any point on the circuit and what the car is doing in any part of a comer, describe perfectly the car at any point on the lap in a lot of detail. He can’t tell you if it needs different springs or whatever, but as long as he’s got someone who can translate his feedback, he’s extremely good technically.”

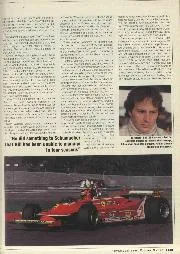

At the end of the season the F1 circus visited America for the final two Grands Prix at Canada and Las Vegas. There was sufficient local interest for Jacquo to rent a drive in the second Arrows at both races. In retrospect, climbing into an F1 car with no preparation, with a team whose resources were stretched tight, desperately trying to make money last until the end of the season, was probably not the smartest move. It was certainly something that Gilles advised against. But Jacques gave it a try anyhow. “It was a spare car and it didn’t work properly,” recalls Jacques. Despite picking up a tow from his brother’s Ferrari at Montreal, he failed to qualify at either event It was the final nail in his coffin as far as F1 went The fact that the engine would barely run long enough for him to complete a lap without it cutting out counted for next to nothing.

In the space of 12 months Jacques had gone from being perceived in F1 terms as the ‘next big thing’ to a slightly sad pale imitation of the revered Gilles. There was another F1 attempt at his home Grand Prix two years later, this time in the hopelessly uncompetitive RAM. Again he missed the cut and the perceptions were sealed.

By then Gilles had been killed and such strange career choices could no longer be tempered by the advice of the one man who could sometimes sway him. There was an emotional ground swell within the family to get Jacques into Gilles’ Ferrari in the aftermath but it was never a serious proposition as far as the team were concerned. By this time Parent had returned to work with Jacques again and hooked him up with Canadian Tire, with whom he ran in the 2-litre class of Can-Am in ’82 and the big capacity class the following year when he took the title.