Humiliated, Mercedes withdrew from racing before the season was over and began making plans for 1937, plans which were to be brought to fruition by Rudolf Uhlenhaut.

In 1984 he told me, “When I joined the racing team I was made technical manager at first and later, technical director. I knew Alfred Neubauer, of course, but I had had no dealings with him up to that point. He organised the team and I handled the technical side he didn’t mess with me and I didn’t mess with him, so we got along well.

“My immediate boss was Fritz Nallinger. Max Sailer remained as nominal head of the department, but he had been responsible for the 1936 season, so he didn’t dare challenge me! I was responsible for building, developing and running the cars.

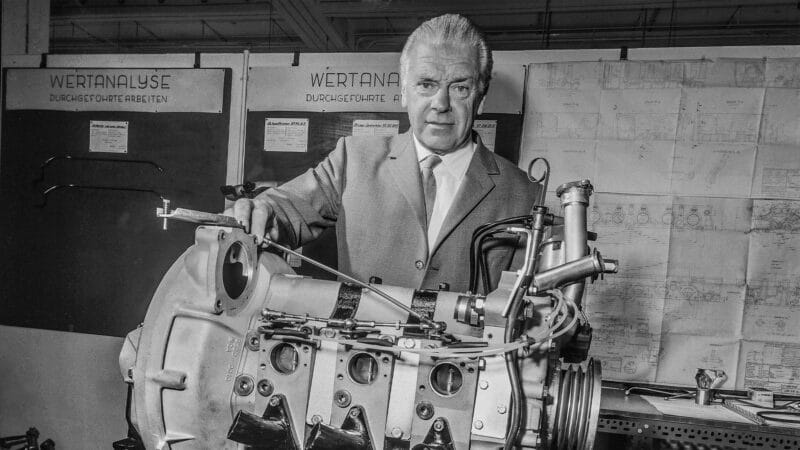

“The problem in 1936 (and before, for that matter) was that Mercedes Benz had nobody in the racing department who could drive the cars, they had to rely on what the racing drivers said and they had no technical knowledge. So, the entire department was reorganised and I was put in charge. I was just 30, which was very young for such a job and I was very surprised to get it.”

Rudolf Uhlenhaut (<em>far right</em>) soon became the driving force behind the on-track triumph of Rudolf Caracciola (middle) and many others

Mercedes

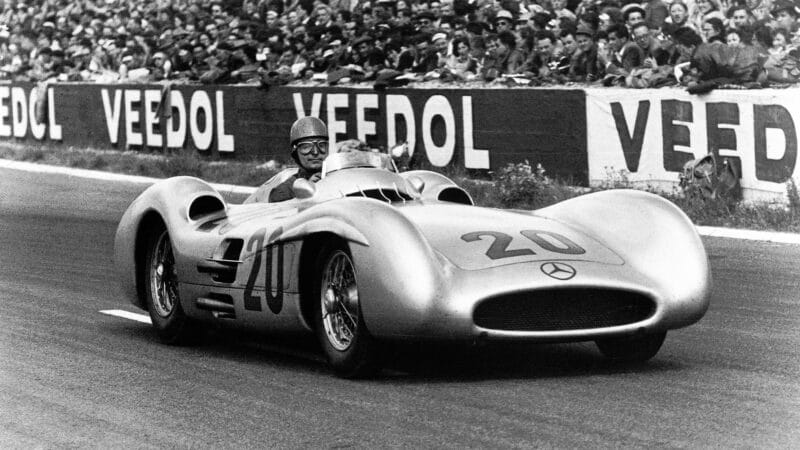

Within days of his appointment Uhlenhaut found himself at the Nürburgring with Rudolf Caracciola, Manfred von Brauchitsch and three grand prix cars, a 1935 model and two 1936 machines. After two days of testing the drivers departed for the Swiss GP at Bern, having made numerous suggestions regarding the cars’ springing.

Left to his own devices “with just a handful of mechanics and no Neubauer”, Rudi decided to see how the racers handled for himself, so he set off round the ‘Ring in the 1935 car, with its swing rear axle, and then a 1936 car, which had a de Dion rear.

“During the four or five years I’d been working on passenger cars we often drove them on the Nürburgring and we always drove them as fast as we could. I found out that driving a racing car was not much different from a passenger car at high speed.” He makes it all sound so easy, but at this point we should bear in mind that we are talking about the old Nürburgring here 17.6 miles (both the Nord and Sudschliefe were then in use) of the most demanding circuit ever built; and that the passenger cars he mentions were the 170 (1.7-litre) saloons. The 1936 GP Mercedes W25 had a 4.7-litre supercharged engine delivering 450 bhp, which was a tad more than that of the 170. Clearly, Uhlenhaut was a driver of exceptional skill with an analytical mind to match.

“My first impressions were of quite simple faults that any engineer could have found. First of all, the frame on both cars was much too weak it bent and vibrated on rough roads. Also, at that time our design department had the idea that the damping of the axle had to be very stiff, so they incorporated both hydraulic and friction dampers. This meant that there was very little movement of the axle against the frame; much of the springing was done in the frame itself. That was completely wrong and the car jumped all over the place because the wheels couldn’t follow the road surface. On one occasion I lost a rear wheel at top speed on the straight. The chassis was so stiff that nothing happened it was just like driving a motorcycle with a sidecar!”