1969 Italian Grand Prix race report: Stewart’s sixth seals it

Jackie Stewart and Matra International, run by ken Tyrell, win the driver’s and constructor’s championships respectively after a thrilling race; top four cars separated by 0.19sec at the finish

Matra's Jackie Stewart won his first F1 title with victory at Monza

Motorsport Images

When practice began a 3pm on Friday there was a feeling of apprehension in the air, for those teams using Cosworth-Ford V8 engines were very jumpy about the recent unreliability of the engines, and the expensive breakages that had been occurring.

Even in pre-race testing there had been breakages, and there was a distinct shortage of engines in the paddock. With all the competitive cars using the Northampton-built engines, Cosworth were almost certain to win the Italian GP, but the big question was “at whose expense?”

Qualifying

Practice had barely begun when Ickx came to rest on the far side of the circuit with his Brabham (BT26-3), having seized the Cosworth engine due to an oil pump failure. Brabham himself was running all right with BT26-4, making his first re-appearance in racing since his Silverstone test-day accident, and Courage was running well with the Frank Williams Brabham (BT26-1), completely rebuilt since its Nürburgring crash. Another car that had been completely rebuilt was the Walker/Durlacher Lotus 49B/7, it, too, having crashed in the German GP.

The works Lotus team had three cars, 49B/10 for Hill, 49B/6 for Rindt and a 4wd car for Miles. While the two old cars were performing well the engine in the 4wd car had a misfire and before it could be found the gearbox chewed up an internal oil seal, which put paid to any further practice. The internals of the centre-mounted gearbox and the fore-and-aft power take off had been completely rearranged since the last race, some major redesigning having taken place.

The Tyrrell team entered three Matras, the two MS80 cars for Stewart and Beltoise, and the 4wd car MS84 for Servoz-Gavin, but this third entry was merely to ensure an alternative car for Stewart, the Frenchman not actually driving it.

The McLaren team did not enter their 4wd car as it was still undergoing some redesigning, and relied on the two cars they have raced all season, M7A/2 for Hulme and M7C/1 for McLaren.

Jochen Rindt put his Lotus in pole position for the race

Motorsport Images

They were not their usual happy selves as Italian law had served a summons on them for a paddock incident of two years ago, and seized their small van as security. However, the racing cars were running well and Hulme was proving to be very competitive. Surtees and Oliver were driving for the BRM team, both with the latest P139 cars, and former with the original car and the latter with a brand new and untried one. The fuel system gave trouble on the brand new car and it was a long time before Oliver could get started. As a stand-by they had the earlier P138 car.

Bonnier was entered with his Lotus 49B, but it was not repaired since its Oulton Park crash so he was a non-starter, but the Swiss Moser was running with his privately-owned Brabham, having recently done some Swiss mountain hill-climbs with it.

Most unusual for any Italian Grand Prix was the sight of only one Ferrari in the pits, and no sign of Enzo Ferrari himself. The car that appeared was 0019, a chassis used already this season, but the engine was of 1968 type. This had the inlets on the outside of the vee and the exhausts in the centre, whereas the 1969 engines had a reversed layout, but it was felt that the 1968 type was more reliable, and at Monza the engines have to work very hard. This car was being driven by Ernesto Brambilla, better known for his F2 Ferrari driving, and one felt that Ferrari was using him as a scapegoat for the fact that the red cars are no longer competitive.

Amon was entered and the intention was that they should practise with the brand new 312B, and if it was competitive he would take part in the race. If not, he would not compete with an old car. The new Ferrari has a flat-12-cylinder engine, developed from the 1965 engine of 1½-litres and this year’s 2-litre hill-climb engine, each of the opposed banks of six cylinders having two camshafts. A completely new back-bone chassis has been built for this car and Maranello was pinning all its faith on it. it was a case of a brand new car, or nothing, as far as Amon was concerned, and as things turned out it proved to be nothing, for the new engine broke while on test at Modena.

This left the meeting with a very empty atmosphere, which was most unusual, for Monza usually produces a paddock full of mechanical interest and new things, and now there was nothing.

With nothing new to be tried and the well-proven cars all a bit apprehensive of their Cosworth engines, practice was not up to the usual Monza standard, and the three and a half hours dragged by.

McLaren’s own car suffered from the dreaded Cosworth disease of a broken camshaft, which meant that the valves and pistons all became mangled together, and it was noticeable that Surtees was doing as much practice as anyone, though his BRM engine was not running properly at high rpm.

As expected, Stewart and Rindt set the pace, but Hulme was right there with them, and Beltoise and Brabham were not far behind, all these being under 1min 27sec for the lap, which was fast but not as fast as expected, bearing in mind that last year practice had nearly seen 1min 26sec broken, Surtees taking the Honda round in 1min 26.07 sec.

There were various fiddlings about with aerofoils and nose fins, all very indecisive, the difference between the aerodynamic aids fixed at minimum-drag positions and no aids at all, hardly affecting lap speeds. Hulme summed it up after trying his car with nose fins and rear aerofoil and without either, when he reported that things were no better and no worse!

Practice on Saturday was for the same time, 3pm—6:30pm which was more than enough time, and once again Ickx was a spectator for his Brabham broke almost at soon as he had started. A spare engine had been installed, but this one suffered a camshaft breakage, as did the engine in Hill’s Lotus.

There were too many Cosworth engines breaking for peace of mind and Cosworth Engineering had explained it as “a bad batch of camshafts”. The trouble was that you did not know you had a bad one until it broke!

BRM were getting a bit desperate in their efforts to make the Surtees car run properly at peak rpm and had fitted ram-boxes over the intakes, but a bad water-pump leak stopped the car’s progress and Surtees practices with the old car.

Oliver was not much better for his engine died on the far part of the circuit when the end fell off the ignition distributor rotor. Aerofoils and fins were continually being taken off and put back, among those experimenting being Stewart, Hill before his engine broke, and Siffert.

The 4wd Lotus was still in trouble with its misfiring engine and Miles spent most of the time doing single laps, finding no improvement, though the gearbox was behaving itself. The Ferrari effort was now confirmed as one rather dated car, and despairing of Brambilla being able to keep up even with the two BRMs and Moser’s Brabham, the decision was made to let Rodriguez try the car.

The Mexican had been hanging around the pits all afternoon and went out first of all wearing Brambilla’s overalls and crash-hat, later changing to his own. Although he beat Moser’s time, he would not beat the BRM’s, but at least he could keep up, so a story was put out that Brambilla had an old arm injury which was giving him trouble, and Rodriquez took his place officially.

Last year, in an identical car, Rodriguez recorded 1min 28.20sec, this time his best lap was 1min 28.47sec! Rindt, Hulme and Stewart were still setting the pace, and all three got below 1min 26sec, Rindt being the fastest with 1min 25.48sec, a speed of 242.161kph. (150mph as near as makes no odds), but there seemed to be a reluctance to go out and thrash round trying to beat each other.

Brabham and Siffert tried vainly to help each improve their times by slipstreaming, but with all the fast cars using Cosworth engines there was not much anyone could gain, unlike the days when Ferrari or Lotus had a definite straight-line speed advantage over their rivals.

Saturday night saw some further engine changing, Lotus borrowing one from Rob Walker to put in the 4wd car as they had failed to trace the misfire, and their only spare engine had to go into Hill’s car and the Brabham team borrowed an engine from Williams to get Ickx into the race, even though he was on the back of the grid, but the young Belgian boy was not exactly bubbling over with enthusiasm for the event.

Race

Jackie Stewart leads into the Curva Sud on the first lap

Motorsport Images

There was a lot of indecision over the use of aerofoils and nose fins, and when the cars assembled at the pits preparatory to the 3:30pm start, it was seen that both McLarens had aerofoils and nose fine, but both works Lotus 49B cars were without either; the Lotus 63 had nose fins and its forward leaning aerofoil, but Siffert had removed all his aids, as had Stewart, though Beltoise retained the lot.

Both the works Brabhams had nose fins and rear aerofoil, as did the lone Ferrari and Courage’s Brabham, but Moser had removed all his. Oliver’s new BRM had nose fins and a two-piece rear aerofoil, one piece on each side of the centre exhaust pipes, while Surtees had a wide deflector plate across the rear of the engine and over the echaust pipes.

“The organisers made a feeble attempt to send the cars off, but it all went wrong because Hulme was not ready to go”

As Stewart had qualified in the Matra 4wd car, as well as his MS80, it was brought to the pits just in case anything went wrong, but it was not needed and was wheeled away when the cars went off on a warming-up lap. In spite of there being only one Ferrari in the race, with virtually no hope of success, an enormous crowd, estimated at 100,000, lined the circuit, but they were quieter than usual, though Stewart, Siffert and Hill were received vociferously.

The organisers made a feeble attempt to send the cars off on the warming-up lap in order of the best practice times, but it all went wrong because Hulme was not ready to go, and was actually last at a time, alternate rows being staggered to the right side.

As Rindt was in pole position, with Hulme alongside him, he should have taken charge of the grid as it moved up to the starting line, but he was more intent on jumping the start than keeping things in order. Instead of moving up to the chequered start-line he hung back, and Hulme hung back with him, while back in the fifth row Hill was nothing like in the right place.

With the front row not coming forward properly the starter panicked and dropped the flag and the 15 cars got away to a rather ragged start. The race was over 68 laps of the road circuit and Rindt made a dragster-like start, followed by Stewart, but Hulme’s McLaren hesitated in second gear and he was engulfed by most of the others.

This hesitation was caused by having a rather higher first gear and second gear, compared with the others using Hewland gearboxes. Needless to say it was Stewart and Rindt who led the pack on the first lap, the Matra and the Lotus being side by side, though the French car was fractionally ahead. McLaren, Siffert, Courage and Beltoise were right on their tails and there was a small gap between them and Hulme, Brabham, Hill and the remainder.

On lap 2 the whole field were nose-to-tail, with Stewart at the head and Moser at the tail, while Ickx went into the pits to report a wavering oil pressure gauge needle. It had been a last-minute rush to get his car finished in time for the start, so it was not surprising that an oil union had not been tightened properly, but it was two laps later before he could rejoin the race in last position.

There was little doubt that this was going to be another Rindt versus Stewart battle, but with the accent being on engine power rather than driving ability it was a question of who was going to join battle with them. The 4wd Lotus lasted but three laps before its borrowed engine broke, and after five laps the race took on a definite pattern. Stewart was determined to lead at all times, mainly to keep ahead of any trouble that might occur from a bunch of cars running so close at an average speed of nearly 145mph, but Rindt was equally determined to not lose an inch, remembering Chapman’s pre-race warning, that the only time he wanted to see him in the lead was on the last lap.

Siffert had command of the rest of the Cosworth-powered cars, McLaren, Courage, Hulme, Beltoise, Brabham and Hill following him in close order. Already the two BRMs were being left behind, as was the Ferrari and Moser’s Brabham. After his bad start Hulme was gaining ground rapidly and on lap 6 was behind Siffert as Brabham went by the pits emitting a puff of smoke from the rear of the engine. He did not reappear for the fuel line to the injection unit became detached, but the smoke was from oil leaking from a joint on the oil filter!

It was Rindt who led at the end of lap 7, and Hulme was now third, for Siffert had had a “moment” braking for the Parabolic Curve and had dropped behind Courage, and next lap the leading bunch appeared out of the Parabolica with Hulme leading from Stewart and Rindt.

Next time round Stewart was leading and the others were lined up neatly behind him in line-astern formation, in the order Hulme, Courage, Rindt, Siffert, McLaren and Beltoise, all being in each other’s slip-steam.

Hill was on his own, some way back, followed by Oliver and Rodriguez at intervals for Surtees was heading for the pits. Two laps previously his engine had sounded a bit flat, and the lap before it had made a very funny sound.

Earlier, the right hand exhaust tail pipe had fallen of Hill’s Lotus, having become detached at the joint where the four pipes merge into one; they wayward pipe had struck the front suspension of the Surtees BRM, denting a wishbone, and then bounced on to the engine and cracked the ignition coil. It was three laps later that the BRM rejoined the race and Surtees had to make another stop before the car got going properly, after which it sounded crisper than a BRM has sounded for a long time.

Moser retired at the pits with fuel feed troubles on lap 10 so that the lone works Ferrrari was now running in last place, apart form Ickx who was two laps behind. This obviously depressed the vast crowd, for they did not seem to mind who was leading the race, there being the same enthusiasm for Stewart, Rindt or Hulme. In spite of the right bank of cylinders exhausting from four short pipes, instead of a long tail pipe, the engine in Hill’s Lotus seemed to be all right and he was gaining rapidly on the bunch of cars in front of him, having a clear track to drive on and an objective to aim for.

Within half a dozen laps he was in the slip-steam of the Matra of Beltoise, who was tailing the leaders consistently and keeping up well, and we now had a group, and there was nothing to choose between any of them, all using Cosworth V8 engines and Hewland gearboxes, though chassis frame and suspensions were spread between Matra, Lotus, Brabham and McLaren and Dunlop, Firestone and Goodyear were providing the grip on the corners.

Stewart led consistently until lap 17, followed at first by Hulme, then by Rindt and then by Courage and on lap 18 the young driver of the Frank Williams Racing Brabham actually led the field over the timing line. Next time round Stewart was back in front, no doubt having made some mental notes of Courage’s driving ability and any weak points he might have.

As the eight cars streamed away on their twentieth lap there was a round of applause from the great crowd of spectators for Brabham, who came walking back to the pits. Collecting some wire and tools he later returned to his abandoned car and refitted the fuel pipe and drove back to the pits, but the leak from the oil filter sealing ring was too bad to allow him to continue.

For three laps the eight drivers maintained station in the order Stewart, Courage, Siffert, Hulme, Rindt, McLaren, Beltoise, Hill and it looked as though a case off “stale-mate” was setting in. But no, on lap 22 Hulme passed Siffert and on lap 23 he passed Courage, and all the while the overall race average was rising steadily, it now being 233.9kph, having started out at 231.2kph this indicated that they were all driving as hard as they could go under the circumstances, and were not playing games for the benefit of the crowd.

On lap 24 the brakes on Hulme’s McLaren began to fail and he dropped rapidly to sixth place, then to eighth and after that lost contact with the leaders completely. The brakes became so inoperative that he gave up pressing on the pedal and relied on using the gearbox to slow up for the corners, having to lift off at 500 metres on the back straight, instead of 150 metres before the Parabolica.

In addition Hulme’s clutch was not freeing so he was changing gear without pressing the pedal and was reduced to cruising round using only the accelerator pedal. Under these conditions he could not hope to keep pace with the leaders, but he was managing to keep ahead of Oliver and Rodriguez who were the only two remaining runners on the same lap as the leader.

On laps 25, 26 and 27 Rindt led, and Stewart dropped back to third place, no doubt summing up the Lotus opposition from behind, as well as watching Courage, who was in second place, and on lap 28 the little Scot was back in the lead.

Piers Courage secured 5th place and two championship points in his Williams Brabham

Motorsport Images

The fire extinguisher on Oliver’s BRM began to come adrift and he was black-flagged in to the pits, which put him two laps behind, and meanwhile the lone Ferrrari was lapped by a great mass of Cosworth power, and Rodriguez could not even keep the red car in the combined slipstream.

Next to drop out of the leading pack was Siffert, when his engine began to go off song and he was back in seventh place by lap 31 and struggling in vain to say with the rest. Rindt led for a lap, then Courage, then Stewart again, while Hill got up to fourth place and this leading group were having a good clean-cut race, for there were not groups of stragglers on the circuit to impede their progress, only Rodriguez, Oliver, Ickx and Surtees who were all spread out and not affecting the issue at all.

On lap 35 McLaren looked as if he was going to lose contact with the leaders, but after a couple of laps he rallied and was on the end of the line of seven cars once again. Hill got into third place on lap 36 and as Stewart crossed the timing line he had the two Team Lotus cars of Rindt and Hill side-by-side behind him and the mythical thought crossed the mind that the two Team Lotus cars could get together and make things difficult for Stewart, for his team-mate (!) was back in fifth place. On the next lap Rindt led, with Stewart, Hill, Courage, Hill, Beltoise and McLaren nose-to-tail behind him.

Having let any likely opposition have a go out in front, so that he could watch them closely, Stewart now led consistently at the end of each lap, though he occasionally let Rindt or Hill go into the lead at the Lesmo corners, only to repass them before the back straight.

The unfortunate Hulme was caught and passed by the leaders on lap 42, and Siffert was falling further and further back. After sitting behind Rindt for a while Hill moved back into second place, and the Austrian dropped as low as fifth, but even when running in-line the six cars passed quicker than you would write down their numbers.

“The unfortunate Hulme was caught and passed by the leaders on lap 42”

At 50 laps the order was Stewart, Hill, Courage, McLaren, Rindt and Beltoise, with Siffert nearly a lap behind and Rodriguez about to pass the brakeless Hulme. Still running were Ickx, Oliver and Surtees, but all too far back to be of any consequence, and Oliver was to disappear shortly when his oil pressure disappeared.

During the next ten laps Hill remained in a very persistent second place to Stewart, and there was something about the way the number one Lotus was pressing on the leading Matra that gave the impression that Hill could well come out the victor at the end of this race.

The fuel-system on Courage’s Brabham began to play up as the tank levels fell and starvation set in, which dropped him rapidly out of the battle, and it must have been heart-breaking for him to feel the car slow right down and watch the remaining five disappear into the distance, especially as he had been in the lead on a number of occasions. By lap 57 he was completely out of sight of the lead and could only hope to keep going to the end, with his engine coughing and spluttering as air bubbles got into the injection system.

With only eight laps left to run the ultimate phase in this fantastic race, of which the average speed had risen to over 236kph, was about to take shape. The order was Stewart, Hill, Rindt, Beltoise and McLaren, two Matras against two Lotus, but this was obviously a race of individuals and not teams, and McLaren was watching them all from the rear. Siffert had been lapped and was also caught by Rodriguez, the Ferrari running strongly but not fast enough.

At 61 laps the order was Stewart, Hill, Beltoise, Rindt, McLaren; at 62 laps it was Rindt in third place; at 63 laps Rindt was in second place. On lap 64 the left-hand drive-shaft on Hill’s Lotus broke and that was his end, so the order was Stewart, Rindt, Beltoise, McLaren. On lap 65 Stewart let Rindt lead into the Lesmo corners, but repassed him again on the back leg, while McLaren got into third place.

The tension was now terrific and Ickx coasting into the pits out of fuel went almost unnoticed. On lap 66 Beltoise was back in third place and the four cars were nose-to-tail. As they raced down the back straight Siffert rounded the Curva Parabolica in a great clud of blue smoke as a piston collapsed and he coasted into the pits.

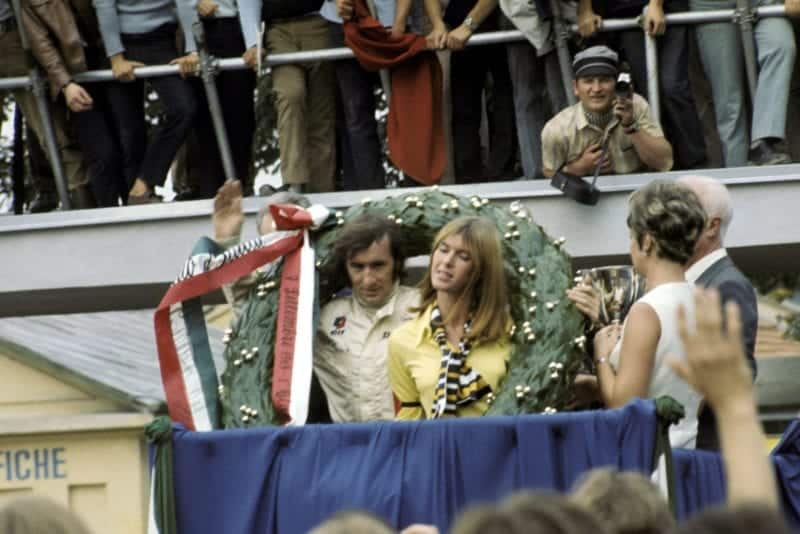

Stewart celebrates on the podium with wife Helen

Motorsport Images

The four cars appeared through the blue haze, the driver’s no doubt on razor-edge reflexes in case there was a car in the smoke haze of oil on the corner, and when they burst into the fresh air it was Stewart, Rindt, Beltoise, McLaren, but it was anybody’s race. Nose-to-tail they started the last lap and into the Lesmo corners Rindt took the lead. Out of the Variante Curve on to the back straight Stewart was in front again.

One more corner to go. Last minute braking for the Parabolica and Beltoise shot by on the inside, in a do-or-die effort that was a personal ambition to win, not a calculated manoeuvre to help his team-mate. Going too fast he ran wide, putting Rindt off any move he was planning and Stewart chopped across to the inside and led out off the corner in the sprint up the finishing straight.

“With Rindt on his right, Beltoise on his left and McLaren behind Rindt the Scot led them over the line in the closest finish for four cars ever witnessed”

With Rindt on his right, Beltoise on his left and McLaren behind Rindt the Scot led them over the line in the closest finish for four cars ever witnessed in a Grand Prix. The time-keepers estimated that nineteen-hundredths of a second covered the four cars.

Not only had Stewart won the 40th Italian Grand Prix but he was now unbeatable on points as the 1969 World Champion Driver, and after six Grand Prix wins nobody will dispute the title. Courage arrived a sad fifth, followed by Rodriguez, Hulme and Siffert, and the huge crown poured onto the track and the presentation of the victors laurels disappeared under a seething mob of wildly enthusiastic spectators.