1966 Italian Grand Prix race report: Scarfiotti brings it home but Brabham is champion

Ludovico Scarfiotti becomes the first Italian to win Italian GP for Ferrari since Alberto Ascari in 1952; Jack Brabham is crowned World Champion

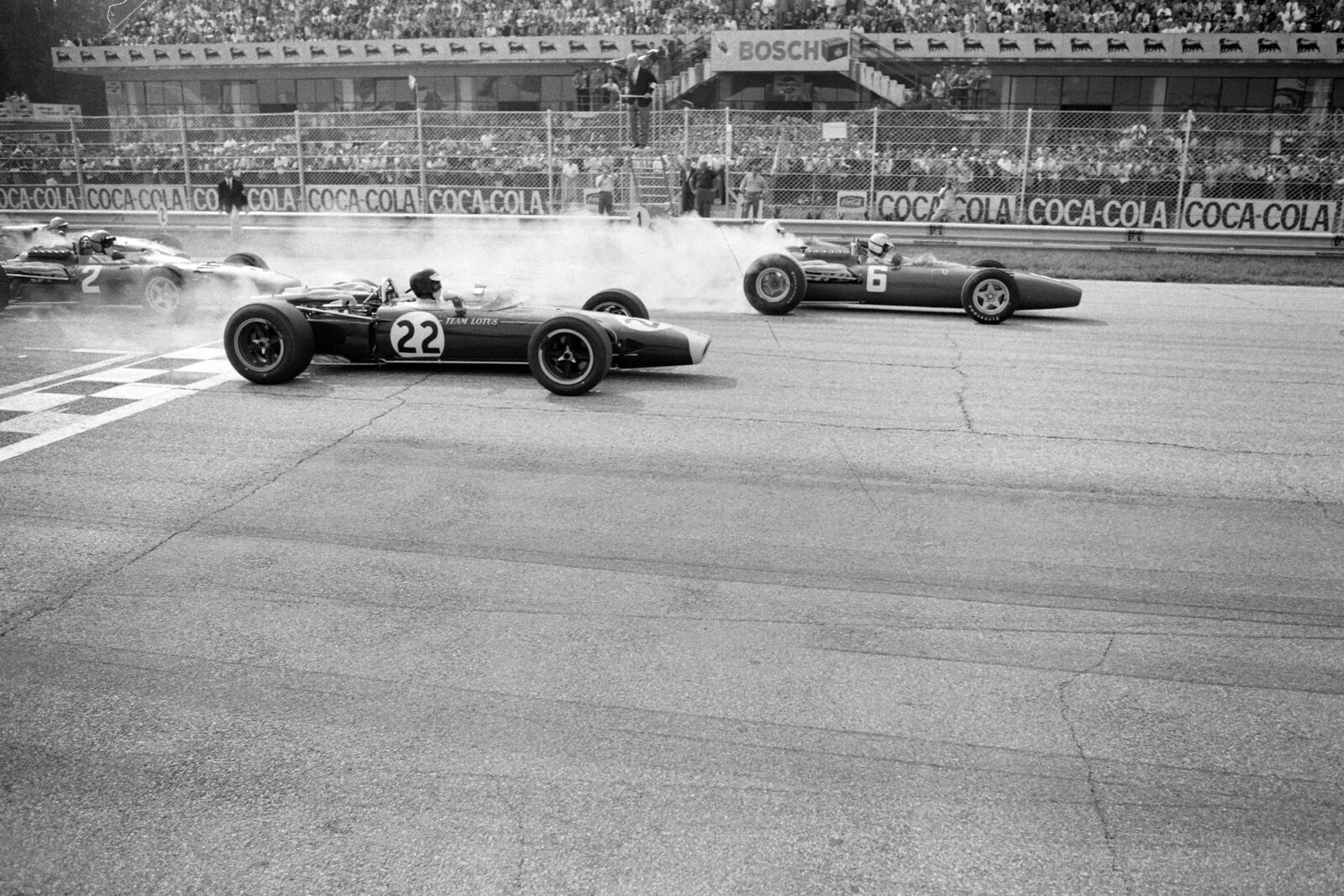

Ludovico Scarfiotti gets the jump on Jim Clark at the start

Motorsport Images

As there was almost a clear month between the German Grand Prix and the Italian Grand Prix all the factories worked flat out to improve existing machinery or to complete new machinery in time for the Monza race, the last of the European classic events. The outcome was an entry of the highest technical interest and the best yet seen in this new era of Grand Prix racing.

There were new cars from Brabham, BRM, All American Racers and Honda, while Ferrari and Maserati produced new versions of existing engines. All these interesting developments are dealt with elsewhere in this issue and with the existing cars in Formula One they resulted in an entry of twenty-two cars.

The Scuderia Ferrari entered three cars with new V12-cylinder engines, to be driven by Bandini, Parkes and Scarfiotti, and Team Lotus also sent a three-car team, consisting of Clark with the new Lotus 43 with H16-cylinder BRM engine, Arundell in R11 with BRM V8 2-litre engine and the young Italian driver “Geki” in R14 with Coventry-Climax V8 2-litre engine.

Brabham and Hulme had the works Brabham-Repco V8 cars, Brabham with the original prototype car with oval-section tubing in the frame, and Hulme with the second of the 1966 cars. They had with them a brand-new car, identical to Hulme’s, for Brabham to try as well as his early car, and all three were using the proven Repco V8 engine.

The works Cooper team were the usual pair, Surtees and Rindt, and their cars had new V12 Maserati engines with the inlet ports inclined inwards, making the power unit more compact. BRM arrived with three 16-cylinder cars, the original Monte Carlo prototype and the improved one that appeared at Spa, plus a third car, which was a brand new one. The two newer cars had improved gearboxes and a new clutch layout and operation, and the car that Hill was to drive had a greatly revised engine which fired as a straightforward 16-cylinder unit, rather than as two 8-cylinder units.

There was only one of these new engines, Clark’s Lotus having the early type as Stewart was using. The BRM team came with the fixed intention of racing the 3-litre cars at all costs, the Tasman 2-litre cars having been pensioned off at last, though one was not far away, being on show in the exhibition in the Monza park organised by the ACI.

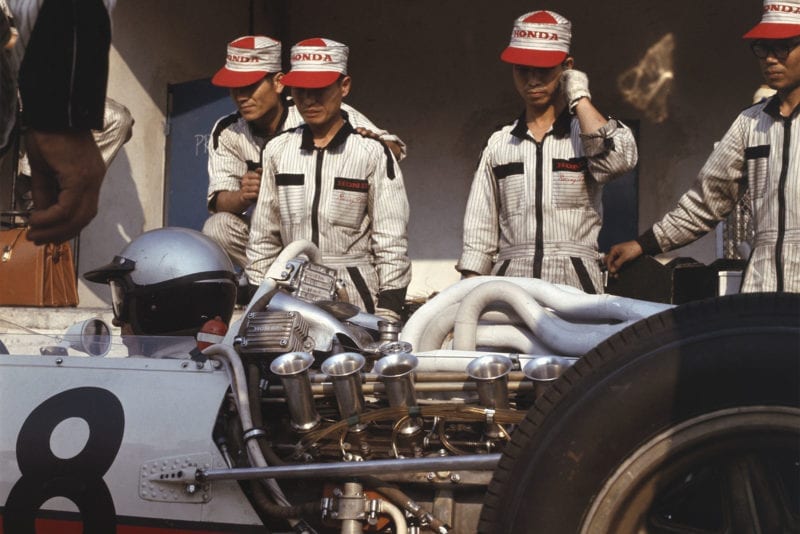

The entirely new Japanese Honda V12 was making its first appearance, in the hands of Richie Ginther, and much was expected of this powerful, but rather large and heavy car. Dan Gurney’s All American Racers team had got their new V12 Gurney-Weslake engine running on the test-bed in the middle of August and the results had been so encouraging that they hurriedly installed it in a new chassis, number 102, and had it at Monza along with the 4-cylinder-Climax-engined car number 101.

As Bruce McLaren’s two entries were withdrawn at the last moment, due to engine problems, Gurney entered Phil Hill on his Climax-engined car, on the proviso that the new V12 ran well enough in practice to take part in the race.

Tim Parnell entered his two Lotus 25 cars, number R3 and R4, for Spence and Baghetti, respectively, and both had 2-litre BRM V8 engines and Hewland gearboxes. Siffert was entered to drive the Walker/Durlacher Cooper-Maserati V12, Bondurant was entered by Bernard White to drive his Tasman BRM V8 and Bonnier and Anderson entered their own cars, Cooper-Maserati V12 and Brabham-Climax 4-cylinder, respectively. With no McLaren to drive, Chris Amon acquired a Brabham-BRM V8 from MGM and entered as a serious competitor, the film-making “circus” once more being back on the job after missing the Nurburgring.

Qualifying

Ginther was entered in the new Honda V12

Motorsport Images

Official practice began on Friday afternoon at 3pm with conditions about perfect and Ferrari, Honda and BRM had already been out testing earlier in the week. The official lap record was set up in last year’s race by Jim Clark, with 1min 36.4sec using a 1½-litre Lotus-Climax V8, while in practice he had done 1min 35.9sec and looking at the quality of the 3-litre cars it was obvious that these times were going to be well and truly beaten, especially as the new Ferrari had already done 1min 31.7sec unofficially and the Honda and Cooper-Maserati had done 1min 34sec without too much trouble.

During the afternoon there was a feeling that as so much of the machinery was brand new there might be a reluctance to push it too hard, but it was a false impression for the pace was very fast, with the V12 Ferraris being unchallenged. At one time the Honda was running in company with the Cooper-Maserati V12 of Surtees and they seemed pretty evenly matched, the Japanese 12-cylinder engine making a glorious sound, but having rather a lot of weight to pull along.

“During the afternoon there was a feeling that as so much of the machinery was brand new there might be a reluctance to push it too hard, but it was a false impression for the pace was very fast”

Siffert was half way round on his first lap when a connecting rod broke and made a hole in his Maserati crank-case and Graham Hill had not done many laps in his 16-cylinder BRM when his gearbox broke. Stewart’s 16-cylinder BRM was going quite well but Clark’s Lotus 43 with similar power unit was going a lot better and showing encouraging reliability, completing a total of 28 laps by the end of the afternoon, without any serious trouble, though the gearbox seemed to lose quite a lot of oil.

Gurney was delayed in going out in the V12 Eagle as the car was being finished off in the paddock, and when he did get going the engine ran well and sounded most purposeful, but the installation of the fuel pumps and pipework was causing starvation on acceleration and by the time the system was modified practice had finished.

In the meantime Gurney and Phil Hill did some practice in the 4-cylinder Eagle, but as it was carrying the same number as the V12-cylinder or it caused some confusion among the timekeepers. Jack Brabham was experimenting with some new Goodyear tyres and one of these experiments sent him spinning off into the sand at the South turn, but no damage was done, and Hulme was getting on with the job in his usual quiet and efficient manner.

BRM were getting in a bit of a shambles, for the spare 3-litre 16-cylinder had wrecked its gearbox earlier in the week, and with the latest car also having gearbox trouble, in spite of the improvements made, Graham Hill had nothing to drive. Contrary to what had been said the 2-litre V8 car was withdrawn from the exhibition and Hill used it to get in some practice at the end of the afternoon. Although the Lotus 43 was going well Team Lotus did not have complete faith in it and the faithful 2-litre Climax-engined Lotus 33 was kept waiting for Clark in case he needed it. so that “Geki” did not get any practice.

The Ferrari team seemed very confident, having no major problems and going very fast, the fastest time by Parkes representing an average speed of 226.725kph (approximately 140mph), while the Maserati element of the Cooper-Maserati combine seemed a hit depressed that Suttees could not match the Maranello cars for speed.

On Saturday practice was again at 3pm, going on until 6:30pm, so that there was ample time for everyone. The Ferrari trio had finished the first practice session in first, second and third positions, and on Saturday none of the three drivers improved on their previous times, but morale was upset a bit when Surtees got among them by beating Bandini’s time by a tenth of a second and Clark then beat Surtees, so Bandini was relegated to fifth fastest and could not improve the situation.

For this practice Surtees had gone hack to using the older type Maserati engine with the wide-angle inlets, and it was fitted with a Marelli coil ignition system, but Rindt kept to his new engine. As Baghetti had broken the gearbox on the car that Parnell had lent him, Ferrari team-manager Dragoni arranged to lend Parnell the 2.4-litre V6 Ferrari that the team used earlier this year, providing that Baghetti drove it, of course.

Throughout the afternoon there was a lot of activity and quite often there were some interesting skirmishes as rival teams came across each other and drivers tried to find out just how fast their opponents could go, or try to get sucked along in the slipstream of faster cars.

For a few laps Stewart (BRM H16), Surtees (Cooper-Maserati), Brabham (Brabham Repco), Clark (Lotus-BRM H16) and Rindt (Cooper-Maserati) began to have a motor race, seemingly forgetting that it was still a practice session, and we had an interesting glimpse of 3-litre Grand Prix racing as it is soon going to be. Lap times were being reduced steadily and last year’s race record of 1min 36.4sec was being surpassed easily by anyone whose car was going properly.

The Eagle’s were having trouble with fuel starvation

Motorsport Images

There was still plenty of trouble about among some of the new works cars, for Gurney was still being plagued by fuel starvation, but when it did get fuel the V12 Weslake engine sounded very healthy. Honda had fitted a complete new exhaust system to their V12-cylinder engine, the four tail pipes having reversed-cone megaphones, but after only a few laps they refitted the system with straight tail pipes, which was not a quick job so that Ginther did not get a great deal of practice. Clark’s Lotus 43 was going extremely well, the 16-cylinder BRM engine and gearbox unit being so reliable that he had almost done a complete race distance and Chapman was sufficiently confident to let “Geki” start practising with the 2-litre Climax-engined car.

Towards the end of the afternoon Clark was seen coasting down the back straight, obviously in trouble, and the Lotus 43 stopped with a slight defect in the gear-change mechanism that was not too serious. just in case it could not be repaired Clark put in some qualifying laps in R14 and “Geki” had to stand down. Brabham was practising in his new car as well as his old one and changing the numbers around so that any very fast laps were accredited to his number for the race.

Gurney never did get his fuel system working properly and the engine continued to stop as he accelerated from the sharp corners so that he could not make a good lap time. On Friday he had put in a lap in the 4-cylinder Eagle-Climax carrying the number of the 12-cylinder car, so this was accredited to him for the starting grid position, for timekeepers are too busy to differentiate between cars, they can only go on numbers.

“The BRM team were almost despondent, for the “museum-piece” 2-litre had broken its engine during the afternoon and out of four cars they had only one still running”

While Team Lotus were very happy with the way their H6 BRM-engined car had performed, the BRM team were almost despondent, for the “museum-piece” 2-litre had broken its engine during the afternoon and out of four cars they had only one still running, this was the car with the latest engine that Graham Hill had started on, and for this second practice it had been fitted with the gearbox/transmission unit from Stewart’s car and had been made to fit the young Scot as he seemed to be the “blue-eyed boy” of the team, but even so he was, only ninth fastest overall; while Clark had got his 16 cylinders on the front row in third fastest position, alongside the works Ferraris of Parkes and Scarfiotti.

The Honda V12 had performed well on its first outing, but not as well as some people expected for it was down on handling, the suspension and steering being far from ideal. The Japanese had made numerous small modifications to the geometry but drivers of slower cars were still finding it in the way on the corners.

The fastest twenty cars were accepted for the starting grid and this meant that Phil Hill and Anion were left out, tor Lotus had repaired the 16-cylinder car, so that “Geki” was able to start with the V8 Climax-engined car, and BRM had a long working session and got two 16-cylinder cars assembled for Hill and Stewart, the former back in the latest car as he had started off on Friday.

The Eagle team were still modifying the fuel system on the V12-cylinder car on Sunday morning, Brabham decided to drive his old original 1966 car and Clark and “Geki” changed racing numbers but not cars. With Amon a non-starter the film-makers were out of step so Spence took number 32 instead of 42 and dressed himself up to look like a film-star. Baghetti was very happy to be driving the borrowed V6 Ferrari and the Ferrari works team were pretty confident about their new 3-valve-per-cylinder engines.

Rob Walker had borrowed another engine for Siffert’s car and he had qualified on Saturday, but Bonnier’s Maserati engine had been having trouble with its fuel-injection pump. Surtees was still using the earlier type of Maserati engine and Rindt the latest type, as regards inlet manifolds.

Each year the ACI seem to reduce the length of the Monza race and this time it was down to 68 laps of the 5.75-kilometre road circuit, with the start due at 3:30pm when the sun was not quite so hot. All but four of the starters went off on a warm-up lap, Siffert being content to push his car to the starting grid, but Gurney was late in coming out due to last-minute detail work, Surtees was late out due to a rubber fuel tank having sprung a leak and Stewart was suffering from a similar complaint, though more serious for it had leaked into the cockpit and given hint an uncomfortable seat.

Race

Parkes found himself on pole for his team’s home race

Motorsport Images

In view of the complicated nature of a lot of the engines and the fact that they do not want to be kept running in neutral for too long, the start was not good, for the starter kept them on the “dummy grid” too long. Eventually they moved forward to the proper starting grid and Clark was looking anxiously down into the cockpit of the 16-cylinder Lotus, for his fuel-pressure was fluctuating badly and he feared there might be a leak.

Scarfiotti was holding back slightly as was Surtees, both intent on jumping the start. Ginther was revving the Honda pretty high and the sight and sound of the twenty cars was Grand Prix at its best, with seventeen of the twenty starters having lapped faster than the old lap record and sixteen of them faster than the previous fastest time ever recorded at Monza, and the first twelve cars were all 3-litre 1966 cars.

When the flag fell Scarfiotti was already on the move from a few feet behind the start-line and he shot into the lead, with Ginther following him through. Clark muffed his started and dropped the 16-cylinder BRM engine rpm off the power curve so that he crept away with his arm-raised to warn following drivers that he was in trouble. Bonnier also got away slowly as his throttle linkage had broken, but everyone else went roaring off in a cloud of blue smoke from spinning wheels.

“Scarfiotti’s initial lead was short lived and in the cut-and-thrust of the opening lap he got elbowed down the field into seventh”

Scarfiotti’s initial lead was short lived and in the cut-and-thrust of the opening lap he got elbowed down the field and was seventh of the tight bunch of cars that burst into view front the South Curve, the order being Bandini, Parkes, Surtees, Ginther, Brabham, Scarliotti, in Ferrari, Ferrari, Cooper-Maserati, Brabham, Brabham and Ferrari, respectively.

Bandini leads team-mate Parkes in the early battle

Motorsport Images

Rindt and Stewart were leading the rest and Clark went by next to last, but firing on all 16 cylinders and obviously in a great flurry after his terrible start. Graham Hill did not complete the opening lap as his 16-cylinder BRM engine blew up and Gurney took the Eagle-Weslake into the pits, followed later by Bonnier.

On the next lap Bandini was missing from the lead and he headed for the pits with a broken fuel pipe, leaving Parkes out in front, but hotly pursued by Surtees, Brabham, Hulme. Ginther and Rindt. At the back of the field Clark had moved up two places and he gained another one on lap three, at which point Surtees took the lead to the accompaniment of cheers from the packed grandstands.

Although the leading bunch of cars were close they were not lapping very last, by practice standards, and Brabham found that he was able to take the lead without too much trouble, lapping at just over 1min 37sec. He led on laps 4 and 5 and began to pull away from the others and meanwhile Clark had joined the end of the pack of works cars. As Brabham passed the pits at the end of lap 6 there was an ominous blue smoke haze coming from the Repco engine, though he had not lost any speed, but Parkes, Suttees, Hulme, Ginther, Scarfiotti, Rindt and Clark must have seen that the Australian’s race was nearly over.

He did one more lap, still with a commanding lead, and the smoke getting worse and at the end of lap 8 he was seen heading for the pits while Parkes went by into the lead accompanied by a great shouting from the partisan crowd. As if to encourage the Brabham pit in their moment of anxiety as they saw “the guvnor” heading towards them, Hulme got past Suttees and was in the slipstream of the leading Ferrari, and while all this was going on Gurney and Bonnier rejoined the race.

Brabham’s trouble was that an inspection plate in the timing cover had become unscrewed and fallen out, and though another one could have been screwed in, the engine had lost quite a lot of oil, which could not he replenished by FIA regulations, and he had lost all contact with the leaders so the car with withdrawn, leaving Hulme to uphold the New Zealand flag.

Scarfiotti now began to improve his position and Bandini had rejoined the race and at ten laps the order was Parkes, Hulme, Surtees, Scarfiotti, Clark, Ginther and Rindt, this lot still being very close together, in line-ahead along the straights and side-by-side through some of the corners. They were followed by Baghetti and Spence running in close company and then came Arundell, Anderson and Siffert, with Bondurant further back and “Geki” bringing up the rear, having already been lapped. Stewart had been forced to give up due to fuel from a leaking tank settling in the driving seat, and Gurney was still in trouble with the fuel system on the Eagle-Weslake.

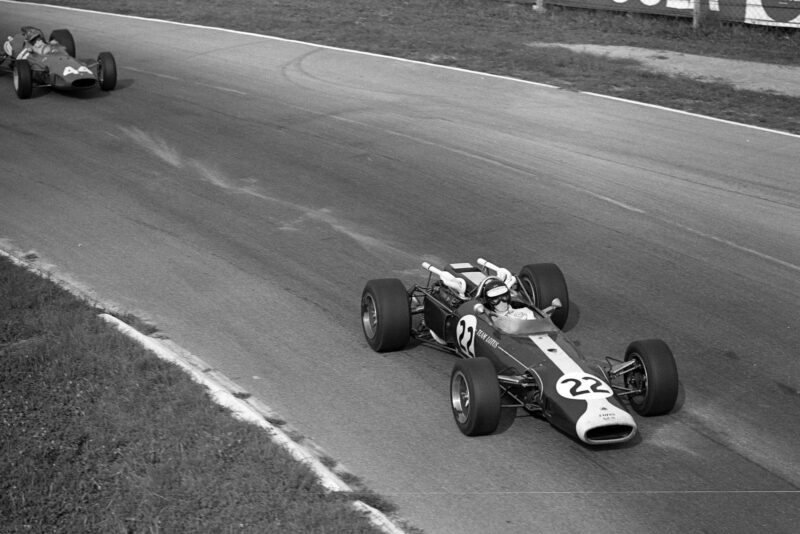

By lap 13 Scarfiotti had moved up into the lead, closely followed by Ginther, the Honda going well down the straights, and Surtees had got in front of Parkes. At this moment Clark headed for the pits with a rear wheel out of balance due to the safety inner-tube in the tubeless tyre having burst and gone to one side of the outer cover, throwing everything out of balance. The wheel was changed and he rejoined the race, but was now in last position, a lap down on the leaders and with no hope of catching up again.

Clark ran with the leading pack until a wheel issue forced him to pit

Motorsport Images

Bandini had waited for his opportunity and joined the leading bunch of cars, even though he was seven laps’ in arrears, and he did his best to help Parkes and Scarfiotti in their battle against the Cooper team, Ginther and Hulme.

“A rear tyre deflated on the Honda and as the car started to swing Ginther put the brakes on to try and steady it, but he lost control and went off the track into the trees, being immensely lucky to escape with minor injuries”

Scarfiotti was now leading consistently, with the Honda holding a very firm second place, followed by Parkes and Surtees, with Bandini hounding them. On lap 17 as a string of cars approaehed the Curva Grande past the pits a rear tyre deflated on the Honda and as the car started to swing Ginther put the brakes on to try and steady it, but he lost control and went off the track into the trees, being immensely lucky to escape with minor injuries for the car was completely wrecked, the monocoque chassis being bent like a banana.

The general pace of the race was speeding up slightly but still was not as fast as practice had indicated, so that Hulme and Suttees were able to keep with the much-faster Ferraris, but they were still being hampered by Bandini who was keeping with them. Gurney had been in and out of the pits and finally the Eagle began to go properly, putting in a lap at just over 1min 35sec, but then the oil temperature began to rise alarmingly so the car was withdrawn.

At 20 laps Scarfiotti still led, with Surtees, Hulme and Parkes in a bunch behind him, Bandini being with them, and Rindt was showing signs of dropping back. Baghetti and Spence were still going round together and then came Arundell and Anderson having a fine race together, changing places continuously, with Siffert a little way behind watching it all. Bondurant, Clark and “Geki” were all a lap behind the leaders, and though the Lotus 43 was going well it could only keep going and do some “race-testing,” it was too far behind to be able to catch anyone.

It was obvious that Enzo Ferrari would want one of his Italian drivers to win, if a Ferrari car was in the lead. and as Bandini was so many laps behind, it was going to be Scarfiotti, providing Suttees or Hulme did not upset things. The job Parkes had to do was to harass these two so that they could not get to grips with the leading Ferrari, and Bandini was there as well, putting his spoke in too.

It was no easy job to deal with two such crafty drivers as Hulme and Surtees and Scarfiotti was not pulling out the lead expected, and on lap 27 Parkes actually led the bunch across the finishing line, but next lap Scarfiotti was back in the lead though Surtees had elbowed Parkes down to third position, but only for a lap.

The two Ferraris were faster than the Cooper-Maserati and the Brabham, but the skill of Surtees and Hulme was making up for the deficiency in speed. Surtees now found that his car was handling in an odd manner and eased off as he thought he had a slow puncture and at the end of lap 32 he headed for the pits, while Bandini went by with his engine sounding rough.

The trouble on the Cooper-Maserati was a split fuel tank and petrol was getting on the rear tyres, causing the unstable feeling, so that was that, and meantime Bandini had stopped with ignition trouble. As the fuel loads had been diminishing the lap speeds, had been rising and Bandini recorded 1min 33.4sec just before his engine went sick, and Scarfiotti was now leading all the time, with Parkes and Hulme behind him, though the Brabham driver was not content with third place and fought Parkes brilliantly giving as good as he got and frequently leading the Ferrari at the end of a lap.

At half-distance, which was 34 laps, Scarfiotti still led and providing the Ferrari kept going there was nothing that was going to prevent him from winning the Italian Grand Prix, for all Hulme could do was to get in front of Parkes occasionally. Each time he did this he was soon relegated to third place by the superior speed of the Maranello car. Clark was now having gear-change troubles and further delays were caused by his battery failing to start the 16-cylinder engine when he was right out of the running and in last place even though the Lotus 43 was going very fast.

Parkes fought with Hulme for second

Motorsport Images

Rindt was in a lonely fourth place and Baghetti and Spence had not changed station and were still on the same lap as the leader. Arundell and Anderson were still battling and passing and re-passing all the time, with Siffert still behind them and Bondurant was falling further back due to a slipping clutch on the ex-works BRM V8.

Bandini’s ignition trouble was cured and he rejoined the race and waited for the leader to catch him so that he could join in with helping Parkes to deal with Hulme. They were now lapping consistently below 1min 34sec. and the New Zealander was giving every bit as good as he got from the two Ferrari drivers and frequently ran round the outside of Bandini when he was in the way on the fast corners.

The two Ferrari drivers had to keep their eyes in all directions in order not to lose the slippery Brabham driver. In all this chopping and changing Hulme improved the lap record twice, with 1min 33sec, on lap 32 and 1min 32.5sec on lap 35, but in spite of this Scarfiotti was pulling out a lead that could now be measured in seconds.

On the leader’s lap 47 Bandini’s ignition played up once more and he was forced to pull into the pits and this time it was for good so that Hulme and Parkes could now race each other without interference. Scarfiotti had ten seconds lead so Parkes could now let Hulme set their pace and merely stay with him to try and demoralise him; a difficult job, for the swarthy New Zealander is made of rugged stuff.

Siffert’s engine went bang and he retired out on the course and just before lap 50 the scene got very busy as the leaders lapped the Baghetti/Spence duo, who were in turn lapping the battling Anderson and Arundell so that parts of the track were very crowded with seven cars in a mixed bunch. In all this Scarfiotti set up a new lap record in 1min 32.4sec. Baghetti got away from Spence and Anderson got away from Arundell, but the V8 Lotus-BRM driver was having trouble with his gearchange and frequently missing gears with consequent astronomical engine rpm.

Clark was still going very fast with the 16-cylinder Lotus-BRM, even though he was many laps behind, and he caught Scarfiotti and lapped at the same speed for many laps, finally passing him and pulling away, which gave Team Lotus great hopes for the future of this car. Baghetti had trouble with his throttle linkage and had to pull into the pits on lap 55 and this delay dropped him front a firm fifth place down to last, letting Spence move up into fifth position.

Ferrari team-mates Scarfiotti and Parkes celebrate their Ferrari 1-2

Motorsport Images

In the closing laps Scarfiotti was able to ease up, letting his lead of over 15 seconds diminish to less than six seconds at the finish, hut there was no danger for Parkes had the measure of Hulme and every time the Brabham got ahead on a corner the Ferrari would steam by down the straights. Clark had been forced out when his gearbox gave trouble, sticking in gear, and his previous stops meant that he had covered insuficient laps to be qualified. With only four laps to go Arundell’s over-stressed BRM V8 engine broke as he went past the pits.

“The Italian Grand Prix had more than lived up to its reputation and had been the best this season and the complete answer to those doubting the 1966 Grand Prix Formula”

As Rindt approached the finishing line his deflated front tyre began to come off the rim and it locked the wheel, so that he skated across the line out of control and ended up on the grass verge undamaged and still in fourth place with Spence in fifth place over half a minute later. Anderson was sixth after a very good drive, having raced with Arundell most of the way and having kept up his excellent standard of reliability with what is now an obsolete Grand Prix car. The Italian Grand Prix had more than lived up to its reputation and had been the best this season and the complete answer to those doubting Thomas’s who have been decrying the 1966 Grand Prix Formula and the new cars.