1963 Italian Grand Prix race report: Clark and Lotus rule supreme

Jim Clark secures the drivers title and the constructors crown for Lotus; intense battle with Surtees ends when Ferrari breaks down

Jim Clark and Colin Chapman celebrate winning the Driver's and Constructor's Championships

Motorsport Images

The Italian Grand Prix being the last Grande Epreuve of the European season everyone was out for a win, although some teams had misgivings as the Automobile Club of Milan planned to use the full 10-kilometre Monza circuit, which includes the banked concrete track as well as the road circuit. Alter the breakages experienced at Nurburgring some of the teams were naturally wondering how their light and fragile cars were going to stand up to the high-speed hammering and centrifugal forces sustained on the bankings. Although practice did not begin until the Friday before the race, there was a great deal of activity at the track during the days before and BRM and Ferrari, in particular, were doing extensive testing.

With Willy Mairesse still on the sick list the Ferrari team co-opted Bandini to support Surtees, which meant that the Centro-Sud team lost their star runner, so their red BRM was loaned to Trintignant. Team Lotus were also in driver trouble, as Taylor was still not completely fit, and as Arundell was entered for a Junior race at Albi the second of the Team Lotus Junior drivers, Michael Spence, was brought into the team to be number two to Clark.

The BRM team of Graham Hill and Ginther were on form, as were Phil Hill and Baghetti for ATS, McLaren and Maggs for Cooper, Brabham and Gurney for Brabham Racing, Ireland and Hall for BRP, and Settember and Burgess for Scirocco-Powell. Parnell entered Amon and Hailwood, and Tim Parnell entered Masten Gregory, while de Beaufort entered himself and Mitter on his old Porsches, and Walker entered Bonnier. The Centro-Sud entered Cabral with their new Cooper-Climax V8 and Brambilla with an old Cooper-Maserati, and private-owners Siffert, Anderson, Raby, Pilette, Lippi, Abate, Starrabba and Seiffert were all entered, making a total of 33 entries.

Of these the fastest 30 were due to take part in the race, practice times deciding the final list, always providing that all the 30 fastest were within 10% of the second fastest time. By this method the ACM were ensuring that the overall quality of the starting grid was high, while at the same time making room for everyone who was worth while.

Practice

Clark prepares to head out on track

Motorsport Images

Before practice began those drivers new to the banked track had to do some qualifying laps at pre-determined speeds in order to get the feel of driving on the high-speed banking, and though some were heard to grumble they should have realised the wisdom of this ruling, which even Fangio and Moss had to abide by in the past. The combined road and track circuit was open at 3:30pm on Friday afternoon for official practice and almost immediately Graham Hill was lapping at very high speed in the 1963 stressed-skin BRM, it now having external water and oil pipes between the engine and the radiators, while the electrical gear previously between the driver’s knees was now mounted in the bulkhead behind his head.

Ginther was also lapping fast in the older car, with 1963 gearbox, and going very high on the bankings, as was Bandini with the latest version of the 1962/3 Ferrari V6 as raced by Surtees at Nurburgring, that is, with bolt-on wheels in place of the old-fashioned knock-off. As the new 6-cylinder car was not ready, Surtees was out in one of the older ones, and gradually most people began practising, Ireland with the stressed-skin BRP car, Clark with the new Lotus 25 that he had raced at Zeltweg, though Spence missed his test-laps so could not practise.

Clark’s number one car was having different springs fitted to it, and Phil Hill was out in Baghetti’s ATS as his own had not yet arrived. The Bolognese cars were looking a lot tidier and clearly the design is becoming settled and parts are being made in a more permanent manner. Carburetters are still used although experiments have been carried out with Lucas fuel injection, and the rubber-ring universals in the drive shafts were replaced by normal Hardy Spicer joints.

Bonnier was driving Walker’s 1963 Cooper, and while settling down to the banking Ireland went by him underneath, going very fast but low down on the banking. McLaren’s Cooper had been fitted with new experimental rear hub-carriers and before long one of the bearings broke up and caused him some anxious moments while going round the banking, and Ireland and Gregory found that the front ends of their cars were sagging as the “rocker arm” top Lotus wishbones had bent due to the suspension bottoming on the bumps on the banking. One or two people were grumbling about having to race on the banked track, but Ferrari and BRM were getting on with the job and doing very well, Hill and Surtees being the fastest at this point.

Then Anderson had his left rear stub-axle shear and the wheel came off while on the south banking and he spun to rest shaken but unhurt, admitting freely that it was the safest accident he could have wished to have, for the guard-rail on the top of the banking kept him going the right way and as the speed dissipated itself he slid down the banking to the soft area at the bottom.

However, this caused the organisers to think deeply, being already aware of opposition to the banking from one or two lesser drivers, and there was a pause in practice while the police made a tour of inspection. They decided that the organisers had not provided sufficient spectator protection around the insides of the bankings and therefore pronounced that they would not sanction further use of the bankings for racing. Why they had not looked at the safety fences before practice began was not explained, but the Automobile Club of Milan apologised to everyone and said that the race would now take place on the road circuit only.

“The police decided that the organisers had not provided sufficient spectator protection around the insides of the bankings and therefore pronounced that they would not sanction further use of the bankings for racing”

While this inspection had been taking place some of the drivers and entrants had been stirring up a petition in the paddock to refuse to race unless the banking was eliminated, but before it could be presented the organisers delivered the Police findings, so everyone was happy and everyones’ faces were saved.

Practice now began all over again, this time on the road circuit only, but there was not much of the afternoon left so it did not amount to a very serious session. However, there were some clear indications, Surtees, Clark and Hill all turning laps in 1min 39sec and a fraction. The timekeepers were normally recording readings to tenths of a second, but where two drivers made equal times they analysed their results more closely and came up with figures to two decimal places. Consequently, Surtees with the 1962/3 Ferrari V6 did 1min 39.58sec, Clark with his usual Lotus-Climax V8 did 1min 39.68sec, and Graham Hill with the 1963BRM did 1min 39.75sec, while Bandini was not far out of the running with 1min 40.1sec.

Spence did not get any practice as while Clark had been using the new Lotus a piece broke off the gear mechanism in the Hewland box and bits got into a ball race, which then became chewed up. Cooper’s had fitted some long thin radius rods from the tops of the rear hub-carriers to the chassis frame by the cockpit, and had tried them in unofficial practice, but removed them by the time official practice began, and after McLaren’s new hub carrier had collapsed they spent the road circuit practice period putting the cars back to standard.

Gurney’s Brabham is worked on

Motorsport Images

The Scirocco team were reduced to only one car, Burgess’s engine not having been rebuilt, and BRP were still lacking a new engine for Hall’s car, after the breakage at Zeltweg the week before. Altogether the Friday was a bit of a shambles as far as serious practice was concerned, except that the three fastest runners indicated an advance over last year’s practice times, when nobody got below 1min 40sec.

Darkness and torrential rain heralded the end of practice, and next morning cloudbursts were still happening, but by lunchtime it was all over and the sun came out and dried everything very quickly. After the previous day’s disastrous practice period the Saturday session was started an hour earlier than scheduled, running from 2:30pm to 6:30pm, and this time Surtees had the brand new 6-cylinder Ferrari out, with the stressed-skin chassis, as described elsewhere in this issue, Bandini having one of the earlier cars.

Of the 33 entries all but five turned out for Saturday afternoon, the absentees being Burgess, still without an engine for his Scirocco-BRM, Mitter, Seifert, Abate and Starrabba, but now that the road circuit was being used for the race the starting grid had been reduced from 30 to 20, so the tail-enders were going to have to scratch a bit to qualify. Spence had taken over the old hack Lotus 25, with the carburetter engine, and Bonnier had both of Rob Walker’s Coopers out in front of the new pits, while Graham Hill went out in his 1962/3 car first of all to set himself a standard before going out in the new BRM.

Although not completely finished, the new pits were in use, having been rebuilt in concrete, some 20 feet farther back from the track than before, with a concrete wall between them and the track, a long gentle sweep into the area from the south turn, and a sharp exit controlled by a traffic light. Altogether a sound and sensible layout, with each pit having a tall chair fixed to the wall so that lap-scorers could see over everything taking place in the pit area.

Settember came in with a very hot “transistor box” on his Scirocco-BRM and firemen were immediately sniffing around the car, but all was well, while the new Ferrari was wheeled away for adjustments after lapping at 1min 42sec Clark lapped at 1min 40.2sec, but Hill improved this to 1min 39.8sec with the old training BRM Spence was starting his first serious Grand Prix extremely well with laps in 1min 44.4sec, a time which Phil Hill was equalling with the ATS.

Nearly an hour had gone by before Gurney turned out in the latest Brabham with single-plane Climax V8 and Hewland-VW gearbox, and shortly afterwards Surtees set off again in the new Ferrari and Graham Hill began practising with the new BRM. Bandini was down to 1min 40.6sec and almost at once Surtees was under 1min 40sec, closely followed by Graham Hill, but meanwhile Clark’s car was being worked on as it was lacking a number of rpm and was not fast enough on the straights.

Graham Hill got the new BRM round in 1min 39.0sec, to which Surtees replied with 1min 38.5sec, and the heat was really on. Phil Hill had got the ATS down to 1min 42.7sec, a time equal to Brabham’s best, the Australian driving the earlier car that he had used at Zeltweg, with the Colotti 6-speed gearbox. Spence was making excellent progress with the old Lotus and was down to 1min 41.8sec, well ahead of both works Coopers and the BRP cars.

“Amon lost it on the second corner at Lesmo and spun off the road, damaging himself rather badly and wrecking the car”

Just before 4pm Amon was beginning to have a go in the Lola-Climax V8 of the Parnell team, when he “lost it” on the second corner at Lesmo and spun off the road, damaging himself rather badly and wrecking the car. Meanwhile Graham Hill, Brabham and Ginther were lapping in close company, and then Clark’s car re-appeared at the pits after having been taken away in the search for the missing rpm. It was not a Clark/Lotus day, for the Scotsman still had to break 1min 40sec on this afternoon, and now Ginther was down to 1min 39.19sec, thanks to some “towing” by his team-mate.

Having done this Hill went ahead on his own and did 1min 38.7sec, followed by 1min 38.6sec, so that Surtees began to sit up and take notice. Brabham was down to 1min 40.4sec and Clark was working away but not getting in the running, his best time being 1min 39.5sec, the Climax V8 still being down on power as it was not pulling maximum rpm on the straights.

The banking was eventually not used in the race

Motorsport Images

By 4:30pm the position was Surtees, G Hill, Ginther and Clark, but Gurney was now in his stride and approaching this select under 1min 40sec group. While the fast boys were battling for the front row of the grid, the private-owners were driving equally hard to get on the back of the grid, and the faster the leaders went the faster the tail-enders had to go in order to stay within the 10% of the second man.

Phil Hill had got his ATS well in amongst the professional teams, such as BRP and Parnell, but Baghetti was way behind and did not look like qualifying for a start. Gregory was making Parnell’s Lotus-BRM V8 go like it had never gone before, and Hailwood was going as quick as Jim Hall, while Ireland had got down to 1min 41.6sec, but Spence had gone even quicker in a praiseworthy 1min 40.9sec in the old works Lotus.

After 5pm the cool of the evening began to make itself felt and G Hill, McLaren, Clark, Maggs and Surtees were all out and going fast. Surtees knocked his time down to 1min 38.0sec, which was greeted by loud cheers from the packed grandstand, and these changed to screams of wild delight when Surtees went round in 1min 37.3sec, a time that nobody could hope to approach. Graham Hill got the new BRM round in 1min 38.5sec but that was his lot, and everyone was looking a bit sideways at Surtees and the new Ferrari V6, especially bearing in mind that they still had 8-cylinder and 12-cylinder engines on the way for the same chassis.

Clark was getting nowhere, it seeming that the Coventry-Climax V8 just was not a match for the BRM or Ferrari engines on sheer power output. He took an opportunity to tuck-in behind Hill on one lap, but the BRM driver was not to be caught, and immediately came into the pits, leaving Clark out in his own draught and going no quicker. Gurney had now joined the leaders with a brilliant 1min 39.9sec, followed by 1min 39.2sec, but Clark had managed to pull out a 1min 39.0sec, so the order was Surtees, Hill, Clark, Ginther and Gurney, and just to show that he was confident Surtees went out and did another lap in 1min 38.0sec; not as good as his best but still faster than anyone else.

Team Lotus were not giving in and had Hassan of Coventry-Climax helping them to find missing rpm and Clark was in and out continually, right up to the end of practice, but he finally had to settle for third best time, nearly 2sec slower than Surtees with the Ferrari, which was an incredible gap for present-day racing. With Graham Hill over a second slower than Surtees, it was obvious that Ferrari were on to something with their new car.

The first twenty times went down to Trintignant with 1min 44.4sec in the Centro-Sud BRM V8, but with Amon in hospital the tail-enders all moved up one and Cabral took the last place on the grid with 1min 44.8sec, minimum qualifying time being 1min 47.2sec. Last year the minimum was 1min 50sec, which gives a good idea of the progress being made in Grand Prix racing.

The lack of rpm in Clark’s engine being untraceable the Team Lotus mechanics put in some overtime and fitted a new engine to the car, BRM were pretty content with their new car and Ferrari were highly delighted with theirs, while Brabham was not exactly unhappy with Gurney’s performance. The timekeepers had split their tenths and given Ginther fourth place with 1min 39.19sec and Gurney fifth place with 1min 39.25sec, but as Ginther had done his time with a tow, Gurney was pretty satisfied.

Sunday morning was occupied by two GT races run over periods of three hours, the first starting at 7am, and a vast crowd poured into the Autodromo, no doubt encouraged by the performance put up by Surtees in practice. An estimated 500,000 people was quoted, and the circuit was packed by midday, the crowd having to watch a Ferrari defeat in the big GT race when Salvadori drove a terrific race with a works Aston Martin DB4GT to beat up Parkes in a GTO Ferrari, after battling wheel-to-wheel for the last 1 1/2 hours of the race.

Race

Surtees took his second consecutive pole

Motorsport Images

The Grand Prix was due to start at 3:30pm and to be held over 86 laps of the road circuit, a distance of 494.500 kilometres, which made lots of teams squeeze the last drop of petrol into the tanks and some fit extra scuttle tanks. The twenty starters were lined up in pairs, stretching for a long way behind the starting line, and a very popular John Surtees was in pole position in the new V6 Ferrari, with Graham Hill alongside him in the new BRM. Last place on the grid was taken not by Cabral as practice times decreed, but by Baghetti with the second ATS.

It seems that a certain amount of “arranging” had been done and Cabral Raby, Settember and de Beaufort had all been encouraged not to start so that Baghetti, who was next on the list, could take the 20th position and uphold the honour of Italian racing! During the morning Chapman was working on Clark’s car, fitting a slightly higher windscreen in place of the usual “air-stream” one.

Most engines were started at the 3min signal, so that the last few seconds before flag-fall seemed never ending, and Surtees began to gesticulate to the starter, and, in consequence, when the start was given he was caught slightly on the wrong foot and made a hesitant start. In the second row, Jim Clark was really keyed up for he knew that unless he could get in behind the Ferrari or the BRM he was going to get left behind, and Surtees’ slight hesitation was just what he wanted, and the green Lotus did a quick ess round the Ferrari and up alongside Hill’s BRM.

Surtees soon got his wheelspin under control and the three cars headed for the Curva Grande in a tight bunch, followed by the rest of the field, who had all got away well. It was the new BRM that was leading at the end of the first lap, with everyone in a tight bunch right behind, and on lap two Surtees got the new Ferrari in the lead for a moment at Lesmo, but was back in second place at the end of the lap, but only by a matter of inches. On the third lap the BRM and Ferrari were side-by-side, with the green car a few inches ahead, followed by Clark (Lotus), Gurney (Brabham) and Bandini (Ferrari), all nose-to-tail.

By the next lap Clark had got into second position and on lap five he had the Lotus so close to the Ferrari tail that he was almost touching. This was Clark’s only chance to get away from the rest of the pack, for Surtees was pulling out a lead but taking the Lotus with him. Gurney and Hill were side-by-side, and Ginther had passed Bandini. Then came Brabham, McLaren and Bonnier, followed by Ireland making up ground for a slow start, and Maggs in the second works Cooper. Gregory in Parnell’s Lotus-BRM was leading the remainder of the field and Hailwood was bringing up the rear, a long way behind, having been in difficulties.

Surtees was using all his old motorcycle tricks to try and get rid of the tenacious Clark, swerving from side to side along the straights, but all the time the green Lotus was right in his slip-stream. Try as he would he could not get rid of the Scotsman, who must have been concentrating really hard on the tail of the red car in front of him, for the slightest deviation from the natural path by the Ferrari and the Lotus was right there. These two were opening up a small gap between themselves and Hill and Gurney, not measurable in time but certainly visible, and any one of the four were in a position to lead the race. They were all lapping at around 1min 40sec and were running away from the rest of the field, that Ginther was still leading, with Bandini hounding him all the while.

“Surtees was using all his old motorcycle tricks to try and get rid of the tenacious Clark, swerving from side to side along the straights”

Ireland was really steaming along in the BRP-BRM and had gone through the Brabham, McLaren, Bonnier trio with little trouble, and was now about to mix it with Ginther and Bandini. Now and then Clark would get alongside the Ferrari, but he could not get by and Surtees was continually trying to get rid of him and for sixteen laps the battle was fast and furious, with Surtees getting all the encouragement from the huge crowd.

Already Hailwood, Baghetti and Anderson had been lapped by the leading quartet, and on lap 17 Clark appeared out of the south turn on his own, and the grandstands groaned, for the Ferrari had blown up. Hill and Gurney went by and then the red car could be seen coasting into the pits, with white vapour coming from the exhaust, a valve having broken and holed a piston.

Surtees had to retire with a blown engine

Motorsport Images

There was no need for the Ferrari pit to inspect the car, they just sadly wheeled it away, and Surtees had to sit and watch the rest of the race, his only consolation being that he had had all the opposition on the run while he was out there racing. This left Clark with 2sec lead, but without the tow from the Ferrari he began to lose ground and it needed only five laps for Hill and Gurney to catch him, and the three of them then raced in very close company. Ireland had got his pale green car between the BRM of Ginther and the Ferrari of Bandini and there he met his match, a three-cornered dice ensuing that was as fierce as the three out in front, for Hill had no intention of letting Clark have his own way, and Gurney will race against anyone given the opportunity.

On lap 21 Trintignant was just leading Hall (Lotus), P Hill (ATS) and Siffert (Lotus), the four of them being line-ahead along the straights, and then the leading trio lapped them, and there were cars all over the place, passing taking place on all sides, and in the ensuing melee Gurney took the lead and Trintignant shook off the remainder of his group. Graham Hill was just in the lead on the next lap, with Gurney and Clark right alongside, and some way back Ginther was being surrounded by Ireland and Bandini, and they had Brabham, McLaren and Bonnier right behind them.

Apart from Surtees retiring there had not been a pit stop up to this point, and on lap 26 Baghetti spoilt the situation when he took his ATS into the pits for attention. Phil Hill in the other ATS, which had been fitted with wheel discs in a vain attempt at streamlining, had been racing successfully with Siffert and Jim Hall, but now began to lose ground to them, and Hailwood had been lapped again, by the leaders, who were still circulating in 1min 40sec.

Gurney would lead, then Hill would get in front, then Gurney again, and then Hill, and once or twice Clark would be in front, but at any given moment any of the three cars could be leading, and more often than not they were side by side. No driver seemed to have any advantage over the other, so it was truly a battle of cars, and they were so evenly matched that the outcome was clearly going to be one of reliability. Already the Ferrari had succumbed, and it was now a matter of seeing if BRM Brabham-Climax, or Lotus-Climax was going to show a weakness.

The drivers showed no sign of weakening and from lap 21 to 42 this three-cornered fight continued unabated. The battle for fourth place was even more fierce, for Brabham shook himself loose from the two Coopers and joined in with Ginther, Ireland and Bandini. Sometimes they would be in line-ahead, and then they would be alongside each other; sometimes Ginther would lead, sometimes Bandini, and so it went on, with the two Coopers of McLaren and Bonnier always just behind them.

Ireland suddenly lost some ground on lap 36 when the gear-change of his BRP gave trouble, but he was able to keep with the group, though no longer challenging for the lead, and then two laps later Bandini was missing, his Ferrari gearbox having broken, and he coasted into the pits to retire. It was hard for the Ferrari team that the two things they normally never have trouble with had let them down in this race, Surtees with the normally reliable V6 engine and Bandini with the old proven design of 6-speed gearbox that has never given trouble.

At half-distance, which was 43 laps, Clark led from Gurney and Hill, but there was still little to choose between them and then came Ginther, followed by Brabham, and then Ireland, McLaren and Bonnier in very close company. A lap behind was Spence, doing very well on his first works drive and leading Maggs, and farther back came Trintignant with the Centro-Sud BRM leading Hall in the BRP Lotus, the remainder having been lapped twice or more, Phil Hill having fallen way behind due to a pit stop for taking on fuel, during which a great deal was slopped into the cockpit.

The ATS had a scuttle tank, connected to the side tanks, and the filler is at the back of the scuttle tank, under the Perspex windscreen, there being a detachable panel in the screen for access to the filler. The other ATS had been in the pits for a long while with electrical trouble, but at least they were both still running, whereas the other red Italian team cars were both in the dead-car park.

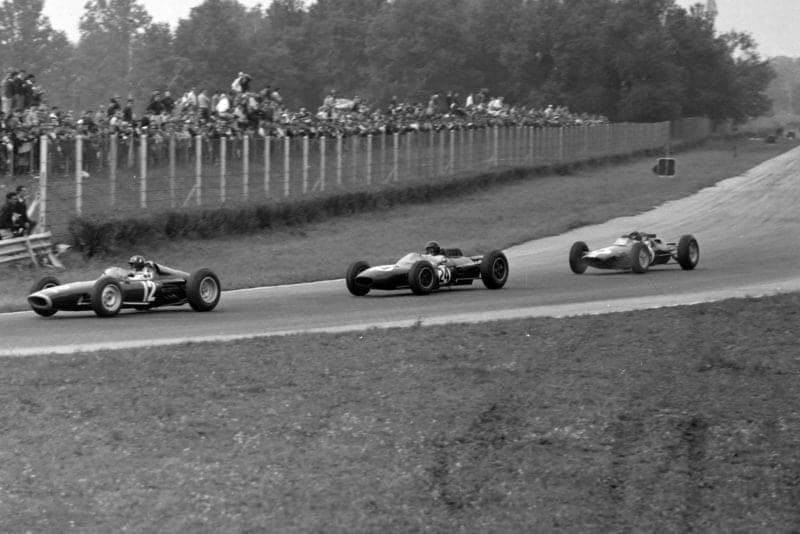

Hill, Gurney and Clark battle through the Curva Sud

Hill, Gurney and Clark battle through the Curva Sud

One lap after half-distance and Gurney was leading once more but Hill had fallen back and lost contact with the other two, and it looked as though the BRM was in trouble. Sure enough, next time round he had lost more ground and it was clear that the clutch was slipping. Hill struggled on for a few more laps but it got progressively worse and on lap 50 he went into the pits to see if anything could be done, but all hopes of a win were now gone. Clark led, and Gurney led, then Clark again, then Gurney, and they were still lapping at 1min 40sec, giving no quarter, and with the challenging Ferrari having broken, and now the challenging BRM in trouble it was proving to be a true race of mechanical endurance.

Ginther was now second, but not very secure, for Brabham was still hounding him, and Ireland, Bonnier and McLaren were still within striking distance. The two leaders were about to lap this group and for a lap or two there was some pretty close motoring going on, especially as Ireland tucked his pale green BRP in behind Gurney’s Brabham and used the slipstream, thereby getting closer to Brabham and dropping the two Coopers a little way back. Graham Hill had rejoined the race after carbontetrachloride had been squirted into the clutch, but it was of no avail and he did a few more laps to the sound of suffering clutch plates and finally called it a day.

“Clark was now beginning to hold the lead consistently, but Gurney was always right on his tail”

Clark was now beginning to hold the lead consistently, but Gurney was always right on his tail, and they finally managed to get past Ginther and Brabham on lap 60, so that they had lapped the entire field, but Ginther was doing his best to keep in their draught and rid himself of the tenacious Brabham.

On lap 62 Clark came into sight on his own, and it was quite a while before Gurney appeared, and after another lap, covered comparatively slowly, the Brabham-Climax headed for the pits, another victim of mechanical unreliability. The trouble seemed to be in the fuel feed and though Gurney made two more laps the trouble could not be cured and he was forced to retire, leaving Clark and the Lotus 25 a whole lap ahead of the rest of the runners.

It had been a pitched battle from the word go between Lotus, Ferrari, BRM and Brabham cars, and the Lotus had come out on top on sheer reliability, though there was still a long way to go to the chequered flag. Clark could now ease up slightly, and his lap times were around 1min 42sec to 1min 43sec, and Ginther followed him closely and Brabham had dropped back slightly. On lap 70 Ireland lapped Spence and Maggs, who were still close together, and the new Lotus team man nipped smartly into the slipstream of the BRP car and got a tow, thus getting away from the second-string works Cooper driver, but only three laps later the oil pressure fell on the Lotus engine and Spence wisely switched off and stopped out on the circuit before he blew the engine up.

On the 76th lap Bonnier’s Cooper engine missed a beat or two and thinking he was running low on fuel he went into the pits to take on a few gallons and lost a certain fifth place. Then Brabham’s engine suddenly cut out and he went onto reserve fuel supply, but the system did not pick up properly and the engine cut out again, so that he also went into the pits to take on some more petrol, losing a certain third place.

Meanwhile Clark was running confidently out in front, content to let Ginther go by and get on the same lap, and with Brabham’s stop Ireland moved up into third place, a position he had worked hard to attain, and he was followed by McLaren, with Brabham back in the race behind the Cooper. With the end in sight Bonnier eased off, thinking Trintignant was more than a lap behind him, where he was officially, but according to most people following the race he was on the same tap as the Rob Walker Cooper, and on lap 83 he went by.

Clark and Ginther were now a lap ahead of Ireland, McLaren and Brabham, and as the Lotus-Climax number one driver finished his 86th lap to win the Italian Grand Prix, Ireland was on the back straight heading for the end of his 85th lap, the chequered flag and a well-earned third place, when his engine seized up solid and he came to a rapid stop.

Nobody was more pleased with this Lotus victory by reliability, and hard driving by Clark, than Colin Chapman and his mechanics, for with wins at Zandvoort, Spa, Reims, Silverstone and Monza it made Lotus the undisputed Champion Manufacturers of 1963, and Clark the undisputed Champion Driver for 1963, and if you add on second place at Indianapolis and first place at Milwaukee you have a driver/car combination that must be champion regardless of any points system.

Clark took his sixth victory and first world title

Motorsport Images

While at Monza for the Italian Grand Prix I had a large helping of “humble pie” for lunch, and I was happy to eat it, for I had just seen Salvadori driving in Aston Martin DB4GT dust-up Parkes in a GTO Ferrari. For many years now I have heard and read about the wonderfully fast Aston Martin GT cars, how they are the fastest production GT cars, how they do 180mph, and so on, but none of it was ever proved; it was all paperwork stuff pushed out by the Publicity Boys.

I always used to say “When I see an Aston Martin blow off all the Ferraris at Monza then twill believe that it is a fast car,” and certain of my Ferrari enthusiast friends used to laugh and say “that will be the day.” Well, that day came, on September 8th in the Inter-Europa Cup Salvadori raced wheel-to-wheel with Parkes for the last 1 1/2 hours of that three-hour race, both of them lapping at 1min 45sec consistently, and while he Ferrari may have gained a slight advantage on the corners the Aston Martin stormed past it time and time again down the straights. Knowing these two drivers, it was enthralling to watch that battle, and there is no doubt in my mind now that the 4-litre Aston Martin GT car is the fastest, but this does not mean it is the best. My only interest was the claim that it was the fastest, and now it has proved it.