1962 Italian Grand Prix race report: Hill takes surefooted victory

Hill streets in adverse conditions ahead of Richie Ginther as BRM make it a one-two; furious battling provides an entertaining race

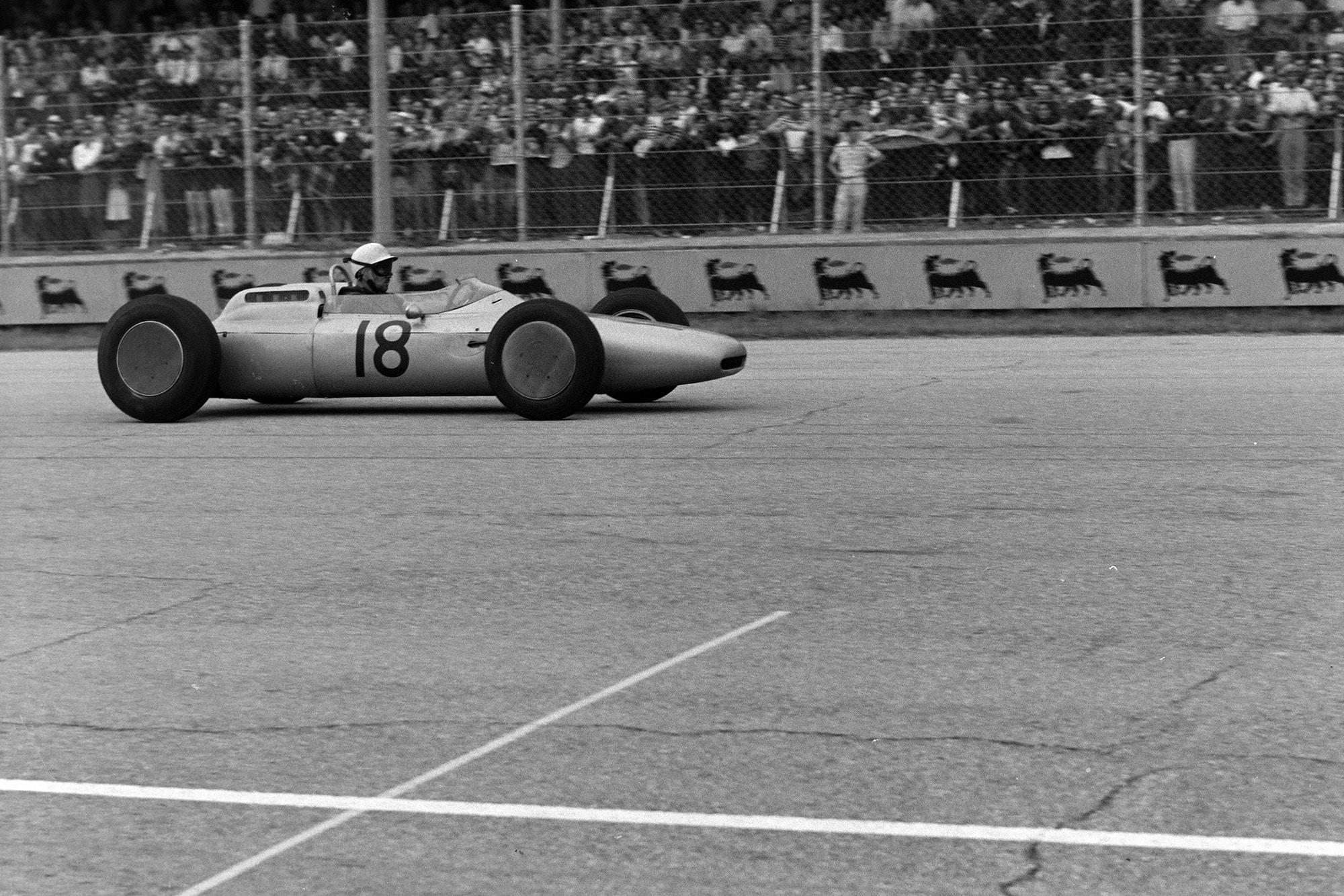

Hill on the way to victory

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

This year the Automobile Club of Milan made two major changes to the Italian Grand Prix, both of them admirable ones. The first was to abandon the concrete banked track and hold the Grand Prix on the road circuit only and the second was to increase the race length to almost 500 kilometres. A total of 31 cars was accepted for the qualifying sessions, of which 22 were to form the grid, these being the fastest during practice.

The Ferrari team were out in force, with Phil Hill, Baghetti, Bandini, Rodriguez and Mairesse but they had nothing new in the way of cars, the best effort being the lightweight car which appeared at Nurburgring. The rest comprised two normal 120-degree-engined cars, one old 65-degree-engined car, and the interim 1962 model with central gearbox that Phil Hill drove at Aintree. There were three brand new cars at the factory with rear suspension like a Lotus but a major error had been committed in copying the geometry and there was not time to correct it, so these cars had to be left behind. The BRM team were well prepared, with cars for Graham Hill and Ginther and a third car as spare, and they all arrived at Monza early and got in some unofficial practice the day before the meeting began, Ferrari also having spent a lot of time going round the circuit earlier in the week.

Porsche also had three cars, Gurney on the newest one, and they had an interesting modification to the cooling-fan drive, incorporating a thermostatically controlled clutch-cum-freewheel so that at maximum speed the drive to the fan could be disengaged, leaving the impeller windmilling at maximum rpm and saving all the power losses involved in the drive. Bonnier was on the second car and the third was a spare.

Other attempts at achieving more speed could be seen in “streamlining” reminiscent of Brooklands in the nineteen-twenties; the wheels had flush-fitting aluminium discs bolted on to the fixing studs, fairings were fitted over suspension members and rear wishbones were taped over to present a smooth surface. In order to check float levels the Weber carburetters were fitted with small external glass riser-tubes which clearly indicated the petrol level.

Team Lotus were endeavouring to get both their drivers in “monocoque” Type 25 cars, Clark in his Oulton Park winning car and Taylor in the newest one, but they had a space-frame Type 24 with them as spare, all three cars having Coventry-Climax V8 engines. The RRC Walker Team had built a brand new Lotus 24 with Climax V8 engine and 6-speed Colotti gearbox, and this car they had loaned to SSS Venezia for Vaccarella to drive, while the original Walker car, which has been completely rebuilt twice this season, was being driven by Trintignant under the Walker colours.

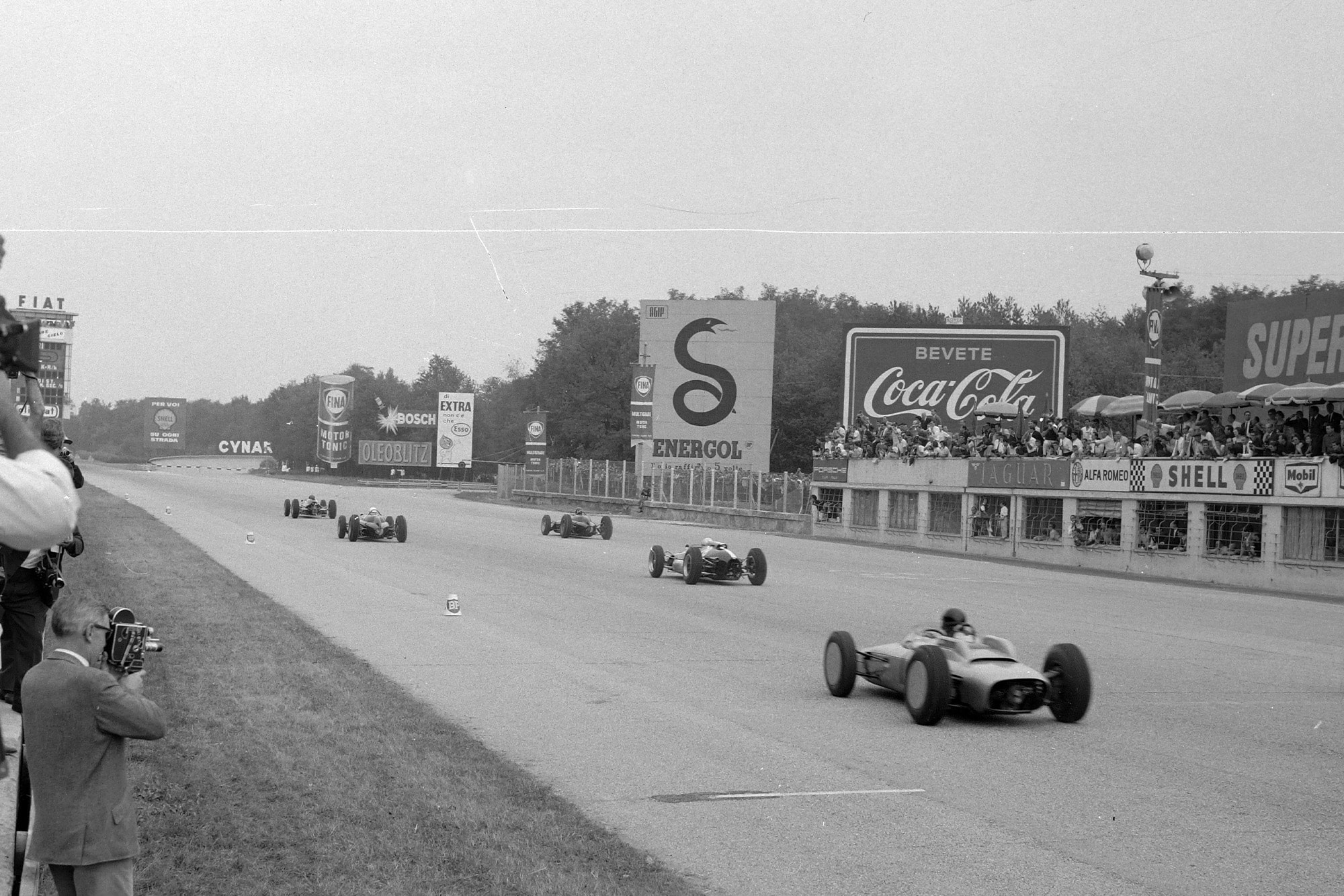

Jo Bonnier in the second Porsche

Motorsport Images

The Cooper team had their usual two cars, with Climax V8 engines and their usual two drivers, McLaren and Maggs, but John Cooper was absent due to his father being seriously ill. McLaren’s car was fitted with oversize fuel tanks alongside the cockpit, making the car more bulbous, and both cars were using 15-in front wheels for this fast circuit.

UDT-Laystall had three pale green Lotus cars, a pair with Climax V8 engines and one with BRM V8 engine, all with 5-speed Colotti gearboxes, and Ireland had the choice of the Climax-engined cars while Gregory had the BRM engined one, this being the team’s original one. Bowmaker had all three Lola-Climax V8 cars, Surtees having the latest one, with stronger front suspension, the cars having pannier tanks alongside the cockpit as a safeguard for the increased race length, while they also had provision for fitting knock-off rear hubs should practice prove the necessity for tyre changes in a race of 500 kilometres.

The rest of the entry was made up of private owners, or small racing teams, and comprised just about everyone in Grand Prix racing today, with the exception of Jack Brabham and his “turquoise-special,” he being unable to agree with the organisers on his monetary value. An interesting entry which made a brief appearance during the first practice, was the new 8-cylinder de Tomaso car, driven by an Argentinian driver named Estefano. This was a car built entirely in Modena, designed by Allessandro de Tomaso and Massimino, and was a most praiseworthy effort on the part of a tiny factory with limited resources. It was not really ready to race, having only recently been out on test at Modena, but made an appearance as a gesture of good faith. This completely new flat 8-cylinder car is described in detail elsewhere in this issue. With such a galaxy of works and semi-works cars in the entry and the starting grid limited to 22 cars, all of which had to be within 10% of the time of the second fastest overall, the chances of the private-owners of qualifying seemed remote, especially those with obsolete cars or 4-cylinder engines.

Qualifying

For a change at a Grande Epreuve there was more than enough time for practice and for preparation, or so it seemed, but even so some teams were unprepared when practice began on Friday afternoon at 3pm to go on until 6:30pm. As one expects of Italy the sun was blazing and conditions were splendid for those who only had to watch, but terribly hot for anyone doing any work. The Ferrari team put Phil Hill out in the centre-gearbox car carrying No.10 and Mairesse in the lightweight carrying No 8, which was a complete reversal of all published lists of drivers and numbers so there were continual doubts and confusion about lap times, but as neither of them were in the running it did not matter very much.

It was the BRM team that set the pace, Graham Hill being much faster than anyone else and returning 1min 40.7sec which was almost equal to the absolute lap record for the Monza road circuit, which stands to the credit of Phil Hill with a 2.5-litre Ferrari in 1min 40.4sec, set up in 1959. BRM were using their newest car, that Johnstone drove at Oulton Park, as a spare, and Porsche and Lola both had training cars out, these cars carrying the letter ‘T’ but their times not counting for qualification.

“Team Lotus were in a bit of a shambles, Clark starting off with his car hopelessly overgeared”

Team Lotus were in a bit of a shambles, Clark starting off with his car hopelessly overgeared, and after having another gearbox fitted in double-quick time this then broke before he got going at all fast; in spite of all this he got in a lap in 1min 41.5sec which gave him second fastest time. His team-mate Taylor, also in a Lotus 25, was having just as bad a time for he had hardly started practice before a rear suspension ball-race broke up and he had to stand around while the suspension unit was changed.

The UDT-Laystall team were getting on with the job, Gregory being just a shade faster than Ireland, the BRM-engined Lotus working very well. However, they had their troubles for Mairesse out in the lightweight Ferrari hit Gregory fair and square up the tail going into the South Curve, not realising that Gregory had only just come out on the circuit and was still warming up. The excitable Belgian was making his first reappearance after his Spa crash and was pressing on as hard as ever. No damage was done to the Lotus-BRM and the Ferrari only suffered a crumpled nose cowling, which was soon hammered out straight again.

Bandini prepares to leave the Ferrari pit as team-mate Baghetti walks by

Motorsports Images

Among the other runners there was plenty of activity, the Scuderia Venezia were finding that a brand-new Lotus-Climax V8 was far from ready to race, Burgess was having a bout of misfiring of a specially-prepared 4-cylinder Climax engine, Prinoth disappeared into the paddock with water pouring from the tail pipe of his old Lotus and Chamberlain had his 4-cylinder Climax engine in bits. The Cooper team had been a bit late in appearing, but McLaren soon got into the groove and did 1min 41.8sec, which just pipped Gregory for third fastest time of the day.

The Lolas were not going as fast as expected, the best Surtees could do being 1min 42.4sec, while Porsches were barely any quicker, their power-saving freewheeling of the fan not showing as much gain on the track as it had on the test-bed. With his own car abandoned out on the circuit with gearbox trouble Clark did a few laps in Taylor’s car, just to see if it was all right. As practice was drawing to a close the new flat 8-cylinder de Tomaso car made a brief appearance, but the clutch was giving trouble so it only did a few laps, stopping at the pits each time, which explains the very long official time that was quoted.

On Saturday practice began again at 3pm to go on until 6:30pm and once more it was very hot. Team Lotus had had another gearbox flown out for Clark’s car but they did not get out of the paddock before that broke, so it was quite late in the afternoon before it was fixed and Clark got out to start serious practice. Then, when he did start the Climax engine broke a tappet! Meanwhile the BRM team were still well in control of the situation, though Graham Hill had not improved on his time of yesterday but was turning consistently fast laps, though Ginther was not improving as his engine was losing water internally and not giving full power.

All the BRMs had been fitted with small tanks alongside the gearbox into which the engine breather pipes were fed and surprise was being registered on how much oil was being caught by these tanks, that would previously have been blown out onto the circuit. Porsche had fitted similar “catch-tanks” at Rouen earlier in the season, and the sooner all racing car constructors follow suit the better for all concerned. Ireland was trying two Climax-engined cars, and altering this and that, and Gregory was still experimenting with things on the BRM-engined Lotus, but from all the confusion they were getting results, both being among the elite who got below 1min 42.0sec.

“The Ferraris were suffering from an overdose of understeer”

The Ferraris were suffering from an overdose of understeer, especially the centre-gearbox car, but while some of the team drivers viewed the situation as hopeless others just pressed on regardless, but even Mairesse could not approach a good lap time in spite of hurling the car through the Lesmo turns with great spirit. Gurney was driving the Porsche through the corners really hard and making some good times, his best being 1min 41.9sec but the flat 8-cylinder engine had not got the steam of the works BRMs.

As the end of the afternoon approached and the air got cooler, nearly everyone went out with a rush to try to improve their times, and the track got so crowded that they all stopped equally quickly. In the Lotus pit there was deep gloom for neither driver had been able to do any really serious practice, and it seemed that anything they touched was going to go wrong. In desperation they put Clark’s number 20 on Taylor’s car and the Scotsman went out for a final fling, and in seven laps not only equalled Graham Hill’s time but improved on it, equalling the absolute record for the road course with a time of 1min 40.4sec, an average of 206.175kph (approx 128mph).

Jim Clark and Colin Chapman converse in the pitlane

Motorsport Images

It took Graham Hill no time at all to put his crash hat on and go out to try to improve on the situation, and he equalled Clark’s time and called it a day. The timekeepers looked closer at their timing apparatus and gave out officially that Hill had done 1min 40sec and 38/100ths and Clark had done 1min 40sec and 35/100ths, so Lotus won the day.

Meanwhile Ginther was out in the spare car, now carrying his number 14 and he did a scorching 1min 41.1sec, which gave him third fastest time, so BRM were sitting pretty. Just as practice ended Taylor went out in Clark’s Lotus, the broken tappet having been replaced and had not done many laps when the gearbox locked-up, so Team Lotus ended practice as despondent as the BRM team were confident.

When all the times were analysed it was found that only 19 cars got within 10% of Graham Hill’s time which was second fastest, so the starting grid was reduced to 21 cars, all having multicylinder engines or works cars, with the exception of the last two who were de Beaufort with his 4-cylinder Porsche and Settember with the 4-cylinder Emeryson-Climax, and both could justifiably feel proud at having got into one of the fiercest and select starting grids, of all time, as 4 sec. covered the first 19 cars.

Although the race was not due to start until 3pm on Sunday afternoon there was plenty of work to do, for Trintignant’s engine had blown up, McLaren had gearbox trouble on the works Cooper, gearboxes were still the headache for Lotus, while the question of fuel consumption was still uppermost in the minds of some team managers.

Race

Clark and Hill lead the field away at the race start

Motorsport Images

In spite of dull weather and other local attractions a very large crowd filled the Monza Autodromo and as starting time approached conditions for racing were perfect, with completely overcast skies, no wind and a cool temperature. The field of 21 cars was lined up in pairs, offset to each other row by row, and everyone was ready to go when the flag was raised. As the last seconds ticked away Graham Hill’s throttle foot became almost frantic and he was giving short staccato jabs on the pedal, the raucous bellowing of his BRM engine could be heard clearly above all the other exhausts as it blipped up to over 11,000rpm.

Down came the flag and Clark made a perfect start and shot into the lead, while Surtees whipped through from the fourth row and, as the whole field surged forward, the blast from the fourteen 8-cylinder, five 6-cylinder and two 4-cylinder engines echoed off the giant cantilever roof of the grandstand in the wonderful noise that makes Grand Prix racing. Clark’s lead lasted just as long as it took Graham Hill to get under way and the BRM led the first lap with twenty cars strung out behind it.

“Down came the flag and Clark made a perfect start and shot into the lead, while Surtees whipped through from the fourth row”

In the short space of the opening lap the field divided itself into two groups, the first one comprising Graham Hill (BRM), Clark (Lotus), Ginther (BRM), Surtees (Lola), McLaren (Cooper), Bonnier and Gurney (Porsches) and Maggs (Cooper). Masten Gregory was leading the second group, having the three red Ferraris of Baghetti, Rodriguez and Phil Hill right behind him, his UDT team-mate Ireland being next to last, obviously in trouble with an engine that would not run properly.

There was no change in the first group on the next lap, except that it was obvious even at this early stage that nobody was going to hold Graham Hill, and on lap three Clark’s Lotus showed signs of seizing its transmission and he came into the pits long after everyone had gone by. Ireland was already at the pits having a carburetter seen to, and soon they both rejoined the race, Clark almost a lap behind, for Graham Hill was rounding the South Corner as the Lotus set off.

A few moments later Ireland rejoined the race not far from the hard battling second group of cars. Graham Hill was drawing away all the time, while Ginther was engaged in a battle with Surtees, and kept a clever pace whereby he held back just sufficiently for neither of them to keep up with the leading BRM. As they were getting away from the two Porsches and the two Coopers anyway, the situation for BRM was a very satisfactory one.

At to laps Hill had 5sec lead over Ginther, who had Surtees right alongside him, seemingly content to let the American set the pace, but on the road Clark’s Lotus was between the two BRMs but one complete lap behind. Then came McLaren, with Gurney closing on him fast, followed by Bonnier, while Maggs had dropped back from this leading group and was being threatened by the second group which was engaged in a fantastic battle. Here there was another rare situation that completely confused anyone not following the race closely, for this second group had Ireland with them on the road, although he was a lap behind on the charts.

He and Gregory were working together to try to get an advantage for UDT just as the two BRMs were doing up in the front of the race, but it was not quite so easy for Gregory had insufficient extra speed to get away while Ireland engaged the rest. Also Ginther was only having to deal with Surtees, whereas Ireland was trying to fend off Mairesse, Rodriguez, Baghetti, Salvadori and Phil Hill, although the last two were not being much trouble.

This little group were getting so worked up that their pace was snowballing and they were not only catching Maggs, who was enveloped on lap 11, but they were also gaining on the Cooper/Porsche dice. On lap 13 Clark was missing from his usual position behind the leading BRM and he arrived slowly at the pits to retire.

Having been caught Maggs now joined in the fun and added more fuel to the UDT fire, and Ireland had yet another car to try to keep at bay. This was no simple give and take battle like one sees at a National event, this was good healthy cut-and-thrust with the three Ferraris doing plenty of thrusting, but they just could not break the solid block formed by the two pale green cars, the only pity of it being that Ireland was a whole lap behind on the reckoning. However, this did not worry him and he and Gregory were having a marvellous time.

Ireland, Gurney and Maggs dice out of the Curva Sud

Motorsport Images

Ahead of them Gurney had forced his way past McLaren and Bonnier was beginning to flag, dropping back slightly so that on lap 19 he was engulfed by the UDT v Ferrari battle, from which Salvadori and Phil Hill had both been dropped. At the tail of the field there was another battle going on, but a more gentlemanly one, between Taylor (Lotus), Vaccarella (Lotus), Bandini (Ferrari) and Trintignant (Lotus), and right at the back the two 4-cylinder cars could do little but tag along. Trintignant’s run came to an end when his electrics went dead, and though he pushed the car to the pits nothing could be done, and shortly afterwards Taylor stopped for attention to the back of the mechanism.

While all this was going on Graham Hill was driving an immaculate and regular race, lapping around 1min 43.0sec and averaging just over 200 kph (approx 124.5mph), increasing his lead all the time without straining himself or the car and at 20 laps he had 11sec lead over Ginther and Surtees who at that point crossed the line side-by-side.

“Graham Hill was driving an immaculate and regular race, lapping around 1min 43.0sec and averaging just over 200 kph”

Gurney was leading McLaren but on the next lap the situation was reversed, and Gregory with Ireland alongside was leading Bonnier, Maggs, Mairesse, Baghetti and Rodriguez. Down the straights the pale green Lotus-Climax V8 was slightly faster than the pale green Lotus-BRM V8 so Gregory tucked into Ireland’s slipstream, but so did all the others. Slipstreaming is always a help, but it means that not so much air is going into the radiator opening and sure enough Gregory was in trouble on lap 23, his water temperature having got dangerously high, so on lap 25 he had to stop and blow off steam, the UDT pit staff wisely having an asbestos glove at the ready for undoing the filler cap.

Ireland continued to press on in the melee of Cooper, Porsche and Ferraris, and he and Maggs then managed to shake off Bonnier and the Ferraris and promptly caught Gurney and McLaren, so that Maggs found himself back where he had started, and on lap 27 he led this group, being in fourth place overall, but on the road Ireland was still setting the pace for this group.

Behind them Bonnier was surrounded by Ferraris and some idea of the tempo can be gained from the lap chart of these four which read successively, 18-2-4-8; 2-18-4-8 ; 2-4-18-8; 18-4-2-8; and so on, and slowly but surely they were making up ground on Gurney and the two Coopers, not forgetting Ireland who was still keeping ahead of them. Salvadori had dropped right back and had suffered the nasty experience of his fire-extinguisher exploding itself in the cockpit, and Phil Hill had clearly given up hope, so much so that he was lapped by the leading Hill on lap 31, well before half-distance.

At 40 laps Graham Hill, serene as ever, had a 20sec lead over Ginther who was no longer being worried by Surtees, the Lola having gone a bit off tune, and though it was 33sec before the next car arrived there was then a lot of activity. Ireland still led Gurney, McLaren and Maggs, with only a few feet separating them and within sight of this trio came Bonnier and the three Ferraris. At half-distance, which was 43 laps, Graham Hill was still lapping most regularly at about 1min 43sec and Ginther came by on his, for Surtees came to rest round the back of the circuit with a broken Climax engine in his Lola, so now it really was a BRM benefit.

But an impending storm was brewing for third position for Bonnier and the three Ferraris had nearly caught Gurney and the two Coopers, and Ireland was still in front of them all, on the road. Salvadori went out with a broken engine and Gregory stopped again, this time with gear-selector trouble and had the box jammed into one gear and continued at a much reduced pace. Graham Hill’s average was gradually creeping up from 200.1kph to 200.4kph, his regularity being brilliant, while Ginther now lapped Phil Hill.

At the end of lap 47 Gurney led the two Coopers, and Bonnier led the three Ferraris and there was about 1sec between the two groups, but Ireland was missing from the front and he drew into the pits to retire with a cracked front suspension upright, leaving the seven possibles for third place to get on with their own battle. Now McLaren led Gurney and Maggs, and right behind them were Bonnier and Mairesse side-by-side, followed by Baghetti and Rodriguez side-by-side, and a little while later Gurney, McLaren and Maggs finished a lap in a dead-heat, three abreast.

The midfield continues to dice on the pit straight

Motorsport Images

The corners were now getting very crowded and just as they were all about to get mixed up Rodriguez dropped back with a sick-sounding engine, but the other six were in a solid bunch, two and three abreast out of the corners. On lap 54 McLaren led from Mairesse, Gurney, Bonnier and Baghetti, while poor Tony Maggs had to drop out of this splendid free-for-all to stop at the pits for more fuel, his Cooper not having the oversize tanks. This dropped him right out of the running, leaving five cars battling for third position, the BRM position being so secure that Graham Hill was beginning to ease off slightly and the race average began dropping.

“On lap 59 there was a roar from the crowd as Baghetti led”

On lap 55 Gurney led the dice, on lap 56 Bonnier led, then Gurney again, and on lap 59 there was a roar from the crowd as Baghetti led. On lap 60 Baghetti had a short sharp spin at the South Curve and dropped to the back of the pack, the others all dodging him by inches, and Gurney led once more. Rodriguez stopped at the pits eventually, to see if his flat-sounding engine could be improved, and on lap 63 a gentle drizzle of rain began to fall and at this the dice for third place cooled off, leaving Gurney in front of McLaren and Mairesse, with Bonnier dropping back and Baghetti making up ground after his spin.

Way behind, Phil Hill was caught and passed by Bandini and Rodriguez was in and out of the pits again. On lap 67 with a steady light rain falling, McLaren and Mairesse appeared on their own and quite a time later Gurney drove slowly into the pits with his crown-wheel and pinion broken. An oil retaining gaiter had split and let all the oil out and the car made such a horrible grinding noise as it stopped that nobody in the pit was brave enough to look closely at it for some time.

With the drizzling rain and having such a commanding lead Graham Hill had now dropped his average speed to just under 200kph and both BRMs sounded as fit and healthy as ever, but McLaren and Mairesse were still racing for third place, the indefatigable Belgian pushing as hard as ever. They lapped Bandini at this point and he tucked in behind them and got a useful tow which took him up closer to Maggs, who was in seventh place after his pit stop.

When McLaren and Mairesse lappd Maggs, Bandini went along with them and snatched seventh place, but the young Cooper driver now kept with them and repassed Bandini. Once more we had four cars in a desperate struggle, one Cooper and one Ferrari fighting for third place, and the other Cooper and the other Ferrari fighting for seventh place, a lap behind, but all four mixing it in together and slipstreaming each other.

Hill lifts the winner’s trophy for the third time that season

Motorsport Images

At 75 laps the rain was stopping and while it had never been enough to wet the track completely, it had been sufficient to slow the tempo of the race. Graham Hill was over half a minute in front of Ginther and not far off lapping Bonnier and Baghetti who were still racing for fifth place, but Bonnier now had trouble selecting gears and dropped back so that he was soon lapped by the leading BRM. Phil Hill stopped for fuel, although his pit didn’t think it was necessary and on lap 83, so near the end, Bandini also stopped for fuel leaving Maggs to hold seventh place.

Graham Hill turned his penultimate lap in 1min 49sec, and then toured home to win, with Ginther in second place, to confirm a result that could not have been improved upon. For the last few laps Mairesse led McLaren for third place, but as they went round on their 86th lap the young New Zealander nipped by the Ferrari with insolent ease and took third place from the very piqued Belgian, who nevertheless was first Ferrari to finish and in a most worthy fourth place. Graham Hill and Ginther had driven the perfect team race, and BRM could have a feeling of pride at finishing up the 1962 European season with such a fine demonstration of strength and reliability.