F1 on water: the America’s Cup craft at the cutting edge of sailing tech

As the 37th America’s Cup reaches its climax in October off the coast of Barcelona, Adam Hay-Nicholls reveals the close ties between sailing’s tech game-changers and Formula 1

Getty Images

America’s Cup yacht racing is often described as Formula 1 on water, but how alike is it really?

Daniel Bernasconi is the man to ask. He spent six years at McLaren before trading asphalt for the salty seas. As technical director of Emirates Team New Zealand, he’s engineered victory in the last two America’s Cups and will be defending his adopted country’s grasp on the silver trophy during the 37th staging of this 173-year-old event, which is being held this month off the coast of Barcelona.

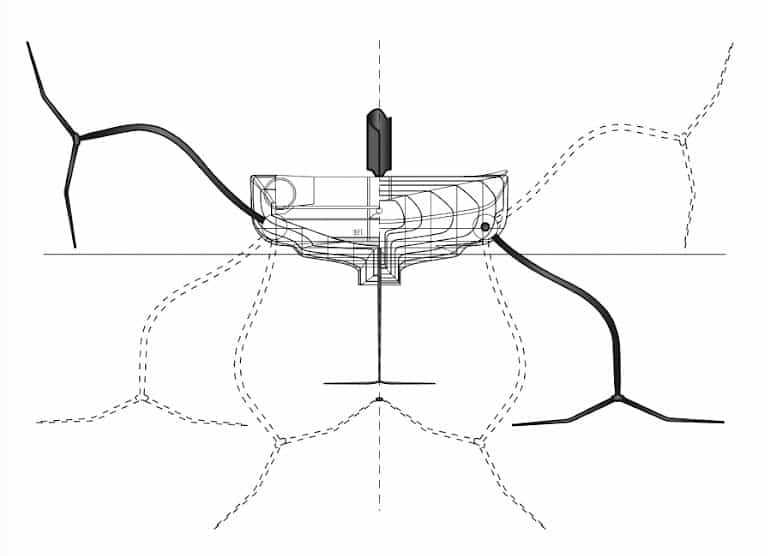

America’s Cup vessels ride above the water, using foils and flaps to give stability.

INEOS Britannia

Daniel Bernasconi formerly worked at McLaren before swapping land for cutting-edge marine design

The 51-year-old Cambridge graduate, from Warwickshire, joined McLaren in 1998 in time to see Ron Dennis’s team sweep to victory in the F1 drivers’ and constructors’ championships that season. Through to 2004, Bernasconi developed mathematical models and vehicle simulations, before diverting his attention from racing cars to boats. While he enjoyed the technical challenges of motor sport, it was, in fact, sailing that had always fired him up. “I learned to sail as a kid,” he says. “This is my passion.” He left Woking to do a PhD in mathematical modelling and aerodynamics at Southampton, for which he was sponsored by the Alinghi America’s Cup team. He contested the 2007 event with Germany’s United Internet squad before joining Team New Zealand at the end of 2010. The current rules ensure that crews are either a citizen of the nation they’re representing, or have lived in that country for a minimum of two years. Dan’s been in New Zealand long enough to acquire a passport as well as the accent.

McLaren win, 1998

Getty Images

Alinghi’s Marcelino Botin and Sam Manuard with Adrian Newey

Alinghi Red Bull Racing

America’s Cup winners 2021

Getty Images

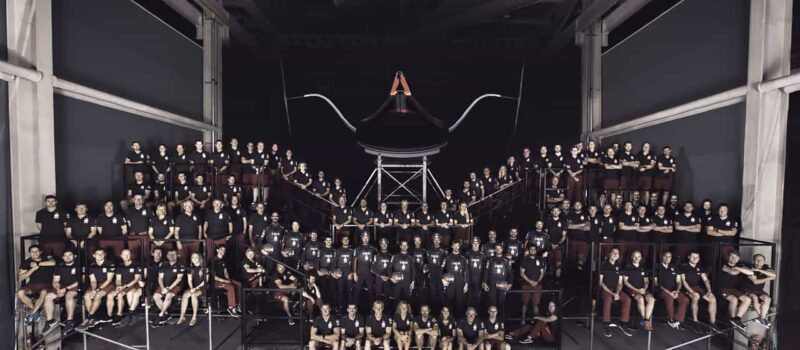

“There are really strong similarities between F1 and America’s Cup, so it was a natural transition,” he explains. “In both cases, you win with a combination of the best technology and the best drivers – or helmsmen. Generally, the race is won by the fastest car or the fastest boat, but if no one has a big technical advantage, it comes down to human beings to extract the maximum from the opportunities. That’s where it comes down to tactics, strategy, and pushing everything to the limit. In F1, you have one driver in each car. In the America’s Cup this year, you have eight sailors per boat. Like grand prix racing, teams field many unseen people working in design, engineering and operations. There are a hundred people working to try and get that car or that boat to cross the finish line first. Team New Zealand’s design office is 45 people alone, and they’re all at the top of their game.” America’s Cup teams spend up to £100m on a campaign. One of the most expensive outlays are the wing-like hydrofoils. “These are very large steel parts and they’re quite intricate. They take a lot of machining.”

“One of the most expensive outlays are the wing-like hydrofoils”

Bernasconi is not the first Formula 1 engineer to make the leap from high-downforce to hydrodynamics. Geoff Willis, previously of Williams, British American Racing, Red Bull and Mercedes, is technical director of the Sir Ben Ainslie-skippered INEOS Team UK, which has a strategic technical partnership with his old Brackley gang. Willis took over the sailing role from James Allison in 2022, with the latter returning his focus to Toto Wolff’s silver arrows. Adrian Newey and Red Bull Advanced Technologies (RBAT) previously worked with Ainslie’s sailing team on the 2017 campaign, where Martin Whitmarsh was CEO at the time. Now, RBAT is working with Alinghi.

The cup is really a design contest

Emirates team new zealand

Carlos Sainz at sea

Alinghi Red Bull Racing

A lightning near miss in the Med in September

There is crossover between the two disciplines, especially when it comes to machining, carbon-fibre composites manufacturing, software, hydraulics, electronics controls and aerodynamics. Really, the only elements outside the Venn diagram are sails and hydrodynamics in one camp, and engines and tyres in the other.

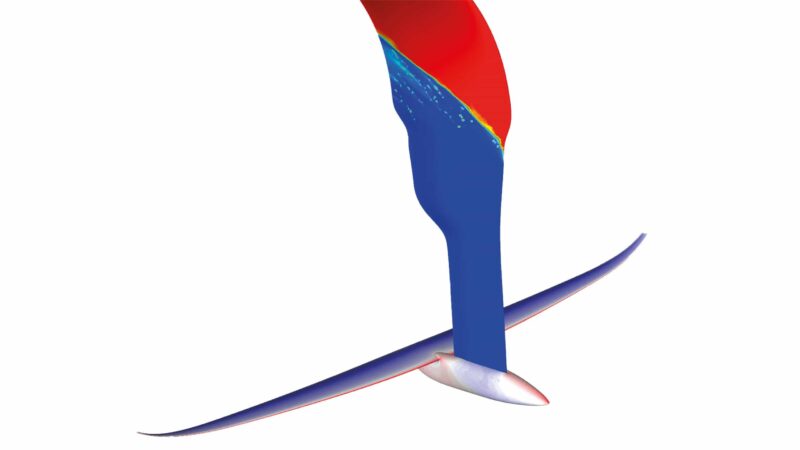

In yacht racing, aero and hydro are of equal importance. “There are gains and losses to be made here, and it’s basically 50/50,” says Dan. “The equation is when a boat is sailing at a speed or on a particular wind condition, then the drive force which comes from the aerodynamics exactly matches the drag, or the drag comes from a combination of the hydrodynamics and the aerodynamics. If you get less drag or more drive it produces the same result: a faster boat. We’ve got aerodynamics specialists and hydrodynamics specialists, and some that are doing both. It is a similar skill set, but just by the nature of it, some people ended up just really focusing on the hydrodynamics, understanding foils, cavitation, ventilation. Some people have gone more into the understanding of sails, which is very specialist in terms of how sails deform under load, so that when it’s got the aerodynamic load in it, it goes to the shape you want it to, and how you can control that shape with all of the sail controls you have available to you.”

“It’s comparable to Formula 1 in terms of the amount of data we generate”

America’s Cup teams don’t use wind tunnels. If they did, they’d have to work with 10% scale models due to the size of the craft. Computational fluid dynamics – which is, of course, how F1 teams do most of their aero simulations too – is the main tool. It’s cheaper and, especially in a racing yacht’s case, more accurate. And let’s not forget, the ocean is less predictable than a three-and-a-half mile asphalt circuit. “In F1, you can get a driver to do three laps with one wing setting, change it and send him out again and compare. You can’t do that in sailing because the sea will be different and the wind will be different. So we make pretty much all of those performance decisions through simulation.”

Foiling boats have been seen in the last four America’s Cup editions, leading some to ask if this is sailing… or something new

With less drag, explosive speed can be reached quickly – even nudging 50 knots.

Alinghi Red Bull Racing

The inaugural Women’s America’s Cup is running alongside the 37th Cup

Alinghi Red Bull Racing

The current technical formula for America’s Cup yachts, known as AC75, prescribes that the vessels are 23m monohulls with hydrofoils mounted under the hull. Fully loaded, they weigh 7600kg with a draft of 5m. There are two semi-battened mainsails and one headsail. The mast is 26.5m tall. Top speed is around 50 knots, or 58mph.

The inaugural Women’s America’s Cup is running alongside the 37th Cup

Alinghi Red Bull Racing

No keel required

Alinghi Red Bull Racing

Like an F1 car, there are hundreds of sensors on board and the data is streamed to the engineers in real time. “It’s extremely comparable to Formula 1 in terms of the amount of data we generate. And we have more cameras. We have cameras looking at the sails, looking at the crew, we might have four cameras under the water, and we’ll have cameras on the chase boat looking at the yacht.” Similar to how Newey and co like to walk up and down the F1 grid spying on their rivals cars, America’s Cup teams all photograph and video each other’s handiwork. Team New Zealand employs two people just to watch what the opposition is doing. There is no FIA-style governing body; instead, the challenger of record and the defender – which this year is INEOS Team UK and Emirates Team New Zealand respectively – work together to determine the regs and enforce the rules.

Yes, simulators are used in sailing too.

Alinghi Red Bull Racing

A ‘sky-rocket’ crash, 2021

Lewis Hamilton visiting INEOS’s base

INEOS Britannia

On the water, the sailing crews work the boat with the well-honed co-ordination of an F1 pitcrew. “The eight crew members are divided into two groups: there’s the power group, running the cyclors [using pedals to raise and trim the sails and move the boom], who are basically head down and putting all the leg muscle they can into the boat. When they’re not at sea, they’re either in the gym or eating. Then there are the four guys who actually control the boat; two helmsmen taking turns to steer, and two trimmers controlling the sail shapes, foil shape and foil altitude control. If a tack goes well, it looks easy, but there’s an enormous amount of choreography involved during every second of that manoeuvre.”

As the defending champions, Team New Zealand must sit on the sidelines during the challenger races which have been underway for the past few weeks until the top contender is revealed. Then, towards the end of October, the Cup will be a match between them (at the time of writing set to be either INEOS or Italian team Luna Rossa Prada Pirelli) and Bernasconi’s boat. The first to seven victories earns the title. “So we only have to beat one team. On the other hand, they’ll have been battle-hardened from the heats.”

The design balances the sail

Leg power is provided by cyclors

Development is comparable with F1

Alinghi Red Bull Racing

For Dan, how has winning the America’s Cup compared with taking Formula 1 world titles with Mika Häkkinen and McLaren? “Winning in Bermuda [in 2017] and Auckland [in 2021] was more rewarding than the world championship. I think the biggest reason is because I’d come so close to winning it with my team twice before. With McLaren, I’d barely arrived when we won, and it didn’t feel like I’d contributed much. Here, the opposite is true, and I feel much more connected to the racing itself.”

A team employees up to 100 people… a fraction of the size of a top F1 team,

INEOS Britannia

AC75 Yacht

Mast Height 26.5m

Crew 8 sailors

Weight 6.5 tonnes

Top Speed Over 50 knots

Hull 20.7m