Jones, Foyt, Gurney and Andretti – America’s golden generation of racers

Following the death of Parnelli Jones over the summer, John Oreovicz lauds him, AJ Foyt, Dan Gurney and Mario Andretti as a generation of US driver legends

Getty Images

Gordon Johncock sat on the outside of the front row of the grid for the 1967 Indianapolis 500, but he wasn’t confident about his prospects. He wasn’t especially worried about pole sitter Mario Andretti, the hotshot 27-year-old who had taken the United States Auto Club Championship trail by storm, claiming the National title in 1965 and ’66. Nor was he particularly concerned about the man in the middle of the front row – Dan Gurney, a fine racer with grand prix-winning pedigree, now driving a car of his own construction called an Eagle.

Lined up inside row two was four-time USAC champion AJ Foyt, the era’s established man to beat – especially at Indianapolis, where he was seeking his third triumph in seven years. Champion motorcycle racer Joe Leonard, another future USAC crown winner, rolled off from the middle, just ahead of the Unser brothers, Bobby and Al, and perennial hard-luck favourite Lloyd Ruby. The rest of the 33-car field included up-and-coming NASCAR stars Cale Yarborough and LeeRoy Yarbrough as well as no fewer than five Formula 1 world champions or champions-to-be: Jim Clark and Graham Hill – the last two Indianapolis winners – along with Denis Hulme, Jackie Stewart and Jochen Rindt.

Gurney was the man responsible for bringing Team Lotus and the Ford Motor Company together in 1963 to ignite a technical revolution that redefined IndyCar racing’s competitive parameters. Just four years after Clark finished second at Indianapolis in a rear-engine car and scored a crushing victory in the Lotus-Ford in 1965, the entire ’67 field was comprised of rear-engine ‘funny cars’.

Except for one.

The STP Turbocar mounted a Pratt & Whitney turbine helicopter engine to the left side of the driver in an asymmetric chassis. The power source emitted a ‘whoosh’ that was nearly silent amid a field of crackling turbocharged Offenhausers and raucous four-cam Ford V8s, and all-wheel drive gave the funky-looking machine rock-solid handling and remarkable acceleration. Parnelli Jones, the 1963 Indy winner, quietly qualified it sixth fastest.

The turbine car was the reason Johncock was so downcast before the race even started. That’s because he turned down the opportunity to drive it. After three weeks of practice and qualifying at Indianapolis, Gordy and everyone else knew the turbine was the car to beat.

“Andy Granatelli came to me at first about driving it in the fall of 1966,” Johncock told Motor Sport a few days before he celebrated his 88th birthday in August. “Andy offered me $80,000 to drive it, and I told him no. I’d have had to switch to Firestone tyres to do it. Goodyear had been my sponsor and been so good to us through the years that I couldn’t just drop Goodyear and switch. He then offered me $100,000, and I said, ‘No, I still can’t do it.’ Then he got Parnelli to drive the car.

“Parnelli was one of the greatest,” added Johncock, who went on to win at Indianapolis in 1973 and ’82. “He didn’t take a lot of crazy chances to hurt himself or somebody else. He was the best. We knew if something didn’t happen to the car, he was going to win the race.”

It took a lot to convince Jones to run Indy in ’67. He hadn’t contested a full Champ Car season since 1964, but his record at Indianapolis was outstanding. He was Rookie of the Year in ’61, qualified on pole at over 150mph in ’62, won from the pole in ’63, then finished second to Clark in ’65. On pavement or dirt, he and Foyt were usually USAC’s drivers to beat in the first half of the decade, but by early ’67, Parnelli had mostly stepped away from open-wheel competition and Andretti had emerged as Foyt’s most credible rival. Meanwhile, Gurney’s influence grew as a car manufacturer and an equally formidable part-time racing driver. The game was rapidly changing.

“The diversity of the Indianapolis 500 brought these four together”

Symbolised by the rear-engine revolution, the unprecedented and unrepeatable diversity of the Indianapolis 500 of the 1960s is what brought these four disparate characters together. Foyt got to Indy first, graduating in 1958 from regional Midget and Sprint Car racing in the south-west to the big national show. Parnelli trod the same path, albeit out west in California; so too did Andretti, on the east coast circuit.

Gurney’s road racing background through sports cars that took him to Formula 1 made him the exception to the rule. But culturally, he had an ally in Andretti, who was born near the Italy/Yugoslavia border and emigrated to the United States when he was 15. The jalopies he found racing dilapidated dirt tracks near his Pennsylvania home required a substantial change in mindset for a young man whose world had revolved around F1 and Alberto Ascari.

The start of the 1967 Indy 500 gets underway, with Mario Andretti, Dan Gurney, AJ Foyt and Parnelli Jones in the front two rows

Getty Images

“I won three races in one day in a Midget in Hatfield, Pennsylvania in 1963, and after the race, I’m sitting there all proud, but I’m thinking about Dan Gurney and Formula 1…somehow, that’s where my mind was, ultimately,” Andretti said. “The bottom line is that I would be inspired by Foyt, by Gurney, by people like that who would move around and do other things.”

The rear-engine revolution coincided with Andretti’s ascension to the top USAC championship cars in late 1964, and it played to his advantage. “In the years preceding the rear-engine cars, it was tough, and you needed big, strong burly guys who could manhandle those cars,” noted legendary crew chief/team manager Jim McGee, who worked with Andretti on and off from the ’60s through to the ’90s. Foyt and Jones certainly fitted that description.

“It was a muscle sport and when the rear-engine cars came along, they made it more of a finesse sport,” McGee continued. “Mario was kind of on an equal footing because all the veterans were on a learning curve too. But Mario was fast in everything.”

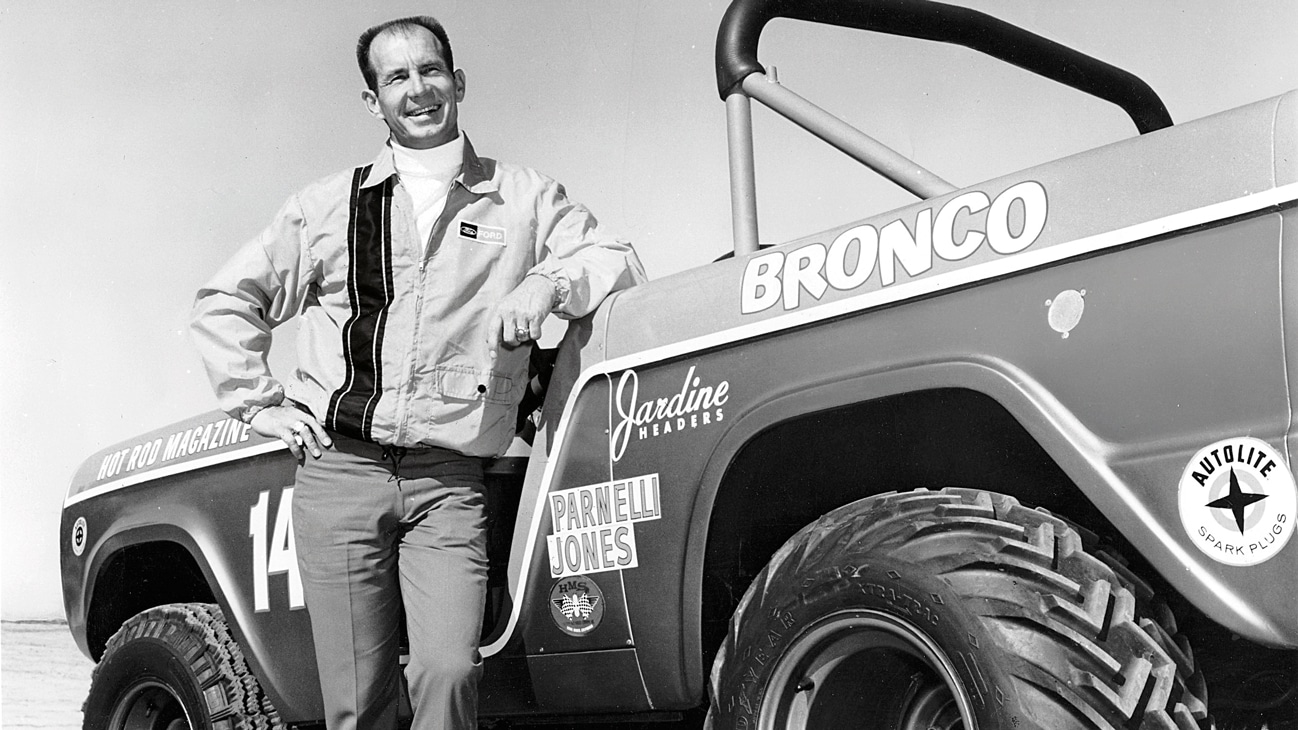

Parnelli was driving the STP turbine car

Getty Images

Jones’s only full-time commitment for 1967 was with Bud Moore to race a Mercury Cougar in the Trans-Am series. Then Granatelli, a master marketer who somehow made STP Oil Treatment a household name in America, came calling with the turbine – and that $100K that Johncock turned down.

When Jones qualified sixth, the competition believed he was not showing the car’s true potential. Gurney was especially dismayed by the radical newcomer.

“The fact that it didn’t make any noise was what wrote it off as far as I was concerned,” Gurney said. “The sounds of different types of engines were extremely important. Now, the fact that Parnelli was doing a great job and that it was a super car, we didn’t like that either. We didn’t have anything against Parnelli. I just felt it was the wrong place for racing it.

“Make no mistake, these were the years when Indy was living up to its fabulous history and reputation.”

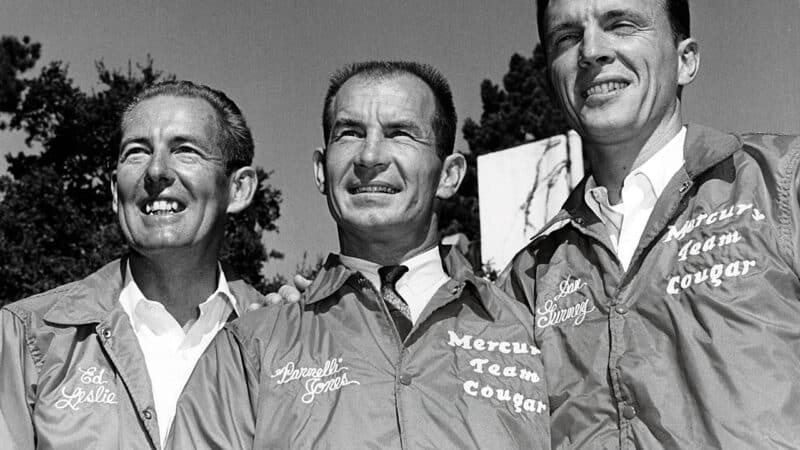

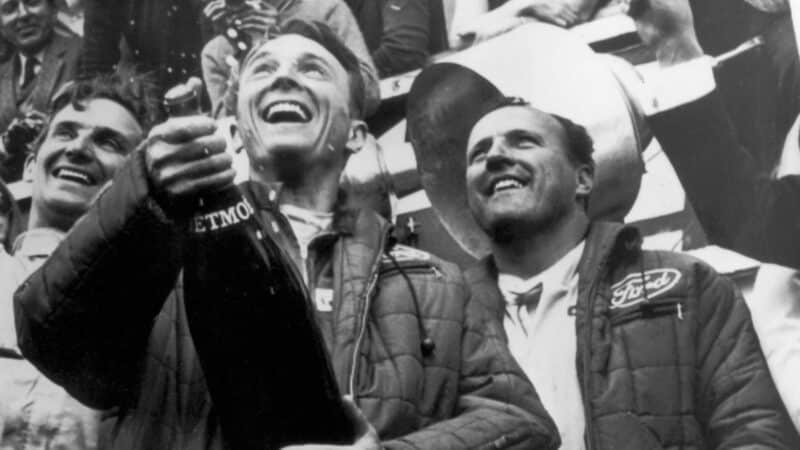

Jones and Gurney, 1967 Trans-Am series

Getty Images

Jones knew the turbine car would come into its own in the race. For starters, its fuel capacity was less than half of the 75 gallons that the ‘standard’ rear-engine cars carried. The top competitors also qualified with a mixture of nitromethane or ‘pop’ in their methanol fuel for a substantial horsepower boost. But Jones never could have imagined he would overtake five cars and blow past pole man Andretti for the lead by Turn 3 of the opening lap.

“There were no rules for the turbine – it was the Wild West,” reflected Andretti. “At the start of the race, on the backstretch he went by me like I was freaking parked. I flipped him a birdie…”

Andretti in the 1969 Indy-winning Brawner Hawk.

Getty Images

“I stuck it in the grey and went around everybody except for Mario,” laughed Parnelli. “With perfect timing, I caught him in Turn 2 and as I was going by on the exit, it’s true, he really did give me the finger. It was all over! Gurney swore that I was sandbagging, but that’s absolutely untrue.”

Jones famously dominated the ’67 500, leading 171 laps until a $6 transmission bearing failed on Lap 197, rendering the ‘Whooshmobile’ totally silent. Foyt, who was leading the race for second behind Jones, picked his way through a last-lap accident to collect his third Indianapolis 500 win.

“Indianapolis is what made AJ Foyt what he is today,” Foyt declares. “I won a lot of great races all over the United States, but I live and breathe Indianapolis.”

Because their driving careers extended into the 1990s, Andretti and Foyt dominate the IndyCar record books, and they remained in the public spotlight far longer than Jones and Gurney. But even though Parnelli and the ‘Big Eagle’ won fewer races than other star drivers of the era like Johncock, Johnny Rutherford and the Unser brothers, Gurney and Jones cultivated an elevated stature in the sport – and more importantly, in American popular culture.

“Mario, AJ, Dan Gurney and Parnelli were all on the cover of Sports Illustrated and the Indy 500 and IndyCar racing was a big deal,” observed the late racing journalist Robin Miller, who went so far as to commission artist Roger Warrick to commemorate Foyt, Gurney, Jones and Andretti as ‘Racing’s Mount Rushmore.’ “When you think about how big the Can-Am was and how big USAC and IndyCar racing was in the ’60s, it’s mind-blowing that it’s gotten to the point where it is today where nobody knows who Scott Dixon or Dario Franchitti or Josef Newgarden are. We have NASCAR heroes like Jeff Gordon, Jimmie Johnson and Tony Stewart, but we don’t have any American heroes in IndyCar racing or international racing like Mario and Dan Gurney in the old days.”

Gurney was part of Ferrari’s 1959 Sebring 12 Hours-winning team

Getty Images

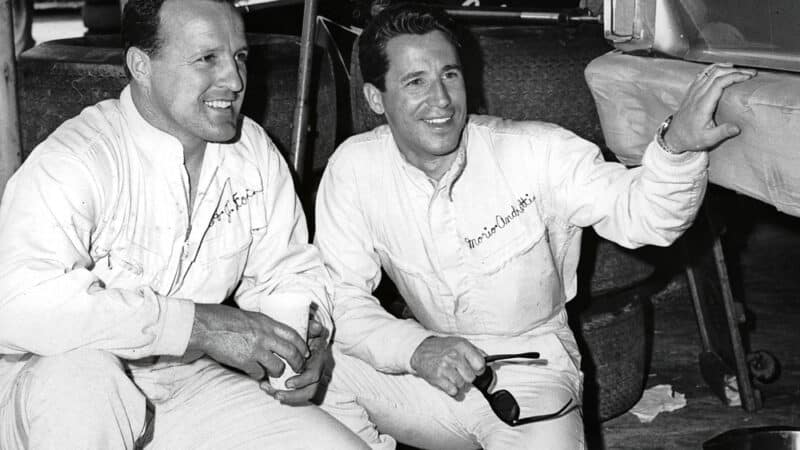

Andretti, Foyt, Gurney and Jones are still collectively revered by American racing fans and a legion of drivers who succeeded them. Each was a true all-rounder, capable of winning in anything they drove. They regarded each other in the highest esteem as competitors, but they didn’t always like each other. The Foyt/Andretti rivalry, in particular, is legendary.

“What must Jim Clark have been thinking when he saw these guys?”

Franchitti, a three-time Indianapolis 500 winner and four-time IndyCar series champion, recognises and appreciates the impact that IndyCar racing’s ‘Million Dollar Quartet’ made on the sport. “When you look at AJ or Parnelli, they’re like the John Wayne of racing cars,” Franchitti says. “I mean, that’s when men were men. Parnelli looks like he’s made out of granite. They were intimidating guys, and to race against them must have been fabulous. What must Jimmy Clark have been thinking when he showed up and saw those guys?”

All smiles between Foyt, and Andretti, but it sure wasn’t always that way. Their rivalry was a running theme for decades

Getty Images

Gurney died in 2018 at the age of 86; Jones died earlier this year at age 90, leaving 89-year-old Foyt – the oldest living Indy 500 winner – and Andretti, the comparative youngster at 84.

Here’s why the reputations of these four legends are carved in stone…

Speed

Speed is a given in champion drivers. Gurney never qualified lower than fifth for his 10 Formula 1 starts for Brabham in 1964. Three years later in a season mostly remembered for the instant dominance of Jim Clark and the Lotus 49 with the new Cosworth DFV V8, Gurney’s qualifying average in the magnificent AAR Eagle-Westlake V12 was 3.9.

“At Jimmy’s funeral, I said to his father, ‘Mr Clark, I’m Dan Gurney,’ he recalled. “He looked up and said, ‘Dan, you were the only driver that Jimmy feared.’ Later on, he sent a recording, telling me that. It’s the biggest compliment I’ve ever gotten as a driver.”

Jones was no slouch. It was regarded as a huge feat when he became the first to qualify for Indianapolis at over 150mph in 1962, where he twice sat on pole and never qualified lower than sixth in seven attempts. His natural speed was also apparent in the Trans-Am, where he won the 1970 championship in what is considered the high point for the long-running sports car series.

Gurney’s first-place at Spa in 1967 gave due notice of what his Eagle was capable of, but six DNFs followed over the next seven F1 races

Getty Images

“We were testing USAC stock cars at Milwaukee in 1965, and I was just not getting close to his time,” Andretti said. “At lunch we were talking, and I said, ‘Parnelli, can I take a ride with you?’ I jumped into the car with him, and I’m hanging on to the rollbars, just watching the way he was feeding the car through the corners. It was like silk. I was fighting the car; I was trying too hard and losing time. I went back out there, and my first lap, I picked up half a second.”

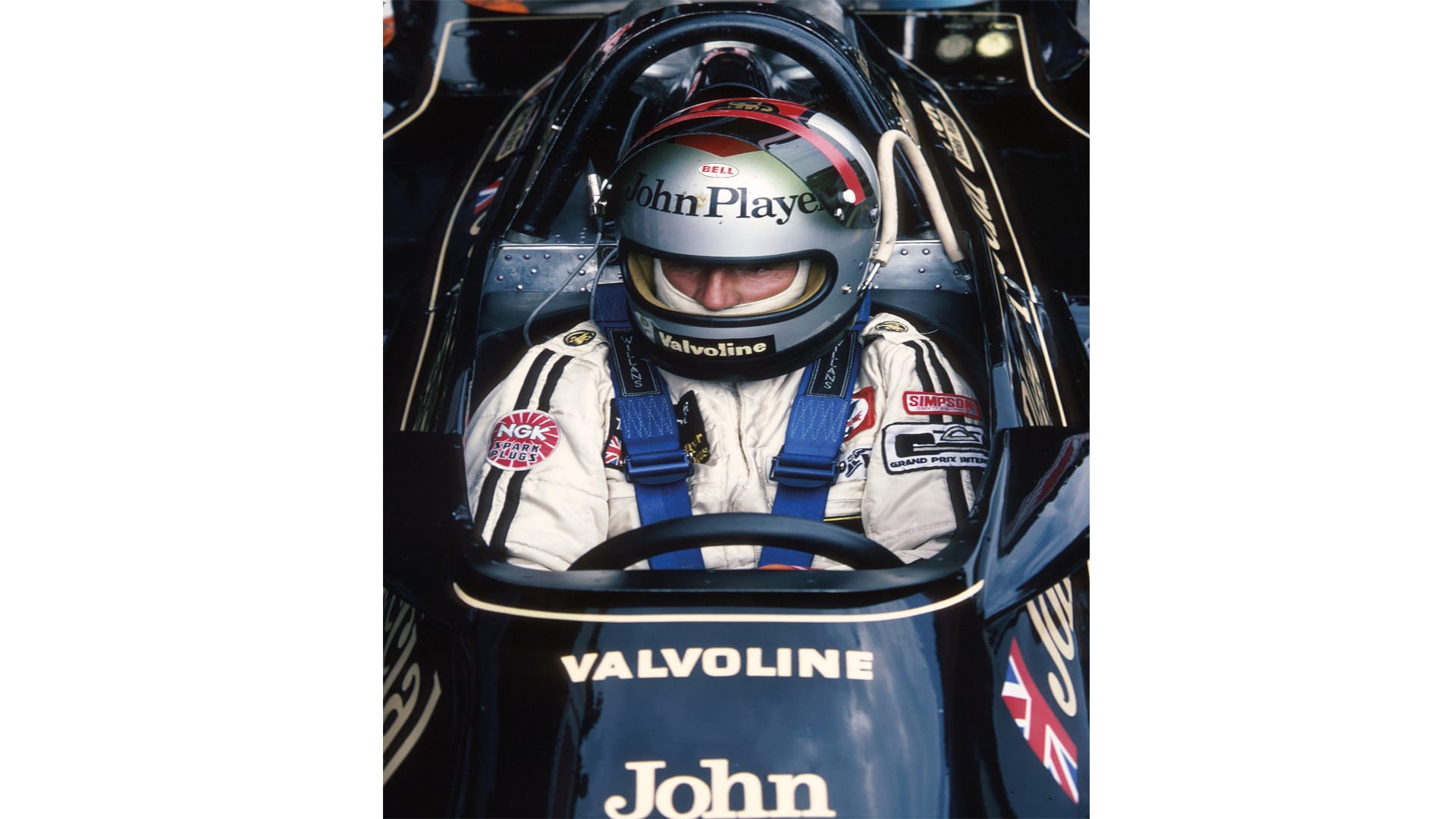

In this group, Mario is the speed king. He was fastest qualifier in 16 of 34 grands prix during his magical 1977-78 run in Colin Chapman’s ground effect-pioneering Lotus F1 cars. For more than 30 years, Mario also held the record for most career IndyCar poles with 67, only recently eclipsed by Will Power.

Foyt had speed; he racked up 52 poles over the course of his long IndyCar career, still third all-time. He sat on the pole for the NASCAR Daytona 500, a race both he and Andretti have won. But Foyt’s biggest weapon was his sheer relentlessness. Through intimidation or pure physical force, he wore his opponents down.

Versatility

Three days before that memorable 1967 Indianapolis 500, Jones dominated and won the Yankee 300 USAC stock car race on the Indianapolis Raceway Park road course. Foyt charged from fifth to second but blew a motor, leaving Andretti to recover from an early spin to claim runner-up honours. All four of these drivers displayed a desire to run as many different kinds of cars as possible, something you don’t often see in the modern era. That’s why it’s such a big deal when a Formula 1 star like Fernando Alonso or a popular NASCAR champion such as Kyle Larson contests the Indianapolis 500.

Cliffhanger: American racing’s ‘Mount Rushmore’, clockwise from bottom left, Jones, Andretti, Foyt and Gurney at a 2017 event

Bernard Cahier

Foyt is most famous for his four Indianapolis 500 wins and seven IndyCar championships, but he also won the NASCAR Daytona 500 and the Daytona 24 Hours sports car race on the road course – twice, in fact. AJ also teamed with Gurney to win the 1967 Le Mans 24 Hours, a week before Gurney won the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa-Francorchamps in one of his own Eagles.

“I didn’t care if it was a dollar purse or a million-dollar purse”

“I guess I was just lucky that I could adapt myself,” Foyt said. “I know a lot of guys who were good in one type of car who couldn’t outrun themselves in a second car. I guess the good Lord gave me that ability when he put me on this earth. I raced everything, everywhere. I didn’t care whether it was a dollar purse or a million-dollar purse. I still gave it 110%.”

Gurney’s CV includes wins in Formula 1, IndyCar, Can-Am and Trans-Am sports cars, and the first-ever Cannonball Baker Sea-To-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash, where he and automotive pundit Brock Yates completed a highway run from New York to Redondo Beach, California in 35 hours and 54 minutes.

Parnelli’s reputation in the ’60s was such that he could have driven anything he wanted and named his price. The only forms of racing Jones missed out on were Le Mans prototypes and F1. “I drove Lotus Indycars for Colin Chapman and he talked to me about Formula 1,” Jones said. “No disrespect to Jim Clark, but I felt Chapman wanted me to be number two to Jimmy and I wasn’t a number two to anybody.”

1985 Daytona 24 Hours winners Bob Wollek, Al Unser Sr, Foyt and Thierry Boutsen

Getty Images

While Parnelli and Gurney stepped out of the car in their thirties to focus on running racing teams and other interests, Foyt and Mario continued driving well into their fifties. Andretti was 53 when he won his last IndyCar race in 1993. Foyt attempted to qualify for the Brickyard 400 at his beloved Indianapolis Motor Speedway until he was 62.

“I loved my driving so much that I just wanted to be driving,” said Andretti, who still takes celebrities out for laps in IndyCar’s two-seater. “I didn’t look forward to a weekend off. I’d go from Argentina to DuQuion, Illinois, Monza to the Hoosier Hundred. From F1 to a dirt car! I used to love that opportunity. I wouldn’t trade that part of my career for anything.”

Results

In America, winning the Indianapolis 500 has always been given greater emphasis than winning a season championship. Foyt’s four Indy wins (1961, ’64, ’67, and ’77) were long considered the gold standard in terms of results among American racing drivers. Three other drivers (Al Unser, Rick Mears, and Hélio Castroneves) have since matched the accomplishment, with Mears doing it in half the starts of the others.

“I just wish some of these younger guys could have seen Foyt when he was young,” noted the late three-time Indianapolis winner Bobby Unser. “Seen how bad he wanted to win races – and therefore set our bar a lot higher.”

Jones on the double, Can-Am ’67

Getty Images

More than any other driver, Andretti is given short shrift because he ‘only’ won the Indy 500 once – the same as Jones, despite Mario making 29 career starts at the Brickyard compared to Parnelli’s seven.

But there is no arguing that Foyt produced two of the finest American national championship campaigns of all time in 1964 (10 wins in 13 races, including Indianapolis) and 1975, when he finished 11 of 12 races in the top three, with seven wins. In all, Foyt won seven open-wheel National Championships, the final two coming in 1979 and ’81 in a much-diminished USAC series. Andretti won three IndyCar titles under USAC sanction and the 1984 CART crown.

“In ’69 I won on the dirt, on pavement, on a road course, and I even won at Pikes Peak on the way to my National Championship,” Andretti recalls. “Those were my glory days to a certain degree because that will never be duplicated, to have that many really different cars to drive for the same championship. I used to thrive on that, personally.”

Despite an Indianapolis 500 victory and 51 other IndyCar race wins, Mario’s greatest accomplishments in the eyes of a worldwide audience are his 12 grand prix wins and 1978 Formula 1 World Championship. It’s staggering and sobering to think that the United States has not produced a grand prix-winning driver in nearly half a century. Like Gurney and Foyt, Andretti also earned several significant sports car wins, memorably teaming with Jacky Ickx at Ferrari in the early 1970s.

Gurney never won at Indianapolis, but he was almost unbeatable in a NASCAR stock car at Riverside in the 1960s, winning five times in seven years. Gurney earned four grand prix victories, including the first for the Porsche, Brabham and Eagle marques, as well as many notable sports car triumphs – including the 1967 Le Mans 24 Hours in a Ford Mk IV teamed with Foyt.

On paper, Jones’s results don’t stack up to Foyt’s or Andretti’s. But he’s the only one of the four to have won the Baja 1000 off-road race (twice), and he and Andretti each scored victories in the Pikes Peak Hill Climb.

Character

Character comes in many forms. Foyt was and is a character; he was often considered hot-tempered and there’s plenty of archival television interview footage if you search on YouTube to confirm that reputation. Jones, as Franchitti alluded, was also a pretty tough character. He famously decked driver Eddie Sachs after Sachs claimed Parnelli’s car was leaking oil during his victorious run at Indianapolis in 1963.

Foyt’s historic Indy 500 win in 1977 put him in a league of his own – at the time, the only driver to have won four times

Getty Images

Gurney was a man of strong character, who believed that American drivers and cars could and should compete with the best in the world. Gurney was also instrumental in the formation of Championship Auto Racing Teams, which essentially took over governance of IndyCar racing in 1979 and convincingly grew the sport for nearly two decades until Indianapolis Motor Speedway management created a second ‘split’ that fractured and devalued IndyCar racing in 1996.

Andretti’s trump card is sheer charisma – his ability to communicate in multiple languages, his jet-set image despite never moving away from the small town of Nazareth, Pennsylvania where his family settled in the 1950s. Mario never deviated into car construction or team ownership, and he remains the true personification of a race car driver.

Legacy

Andretti’s Formula 1 World Championship, when considered on top of all his accomplishments in American racing, combines to give Mario the greatest legacy among Racing’s Mount Rushmore. The Andretti legacy will continue in international motor sport through his son Michael, who is a winner of 42 IndyCar races in his own right, and now a successful team operator with Formula 1 aspirations.

“Foyt, thanks to four Indy 500 wins, stands out for the impact he made on an American audience”

Foyt, thanks to those four Indianapolis wins during the great race’s golden era, stands above the others in terms of the impact he made on an American audience. But what Gurney and Jones accomplished across the sport is still extremely relevant, especially to older racing fans.

Gurney and Foyt made the 1967 Le Mans 24 Hours an all-American victory

Getty Images

As a single-day sporting event, the Indianapolis 500 remains The Greatest Spectacle in Racing. But no driver in the modern field, with the possible exception of NASCAR star Larson, has the ability – and perhaps more importantly, the desire – to push themselves to compete at the top level in multiple forms of racing like Foyt, Andretti, Gurney and Jones did in their heyday. Larson entered nearly 100 races during his 2021 NASCAR Cup Series championship year, winning more than 30 times in stock cars, Sprints, Midgets and Late Models. In 2024, he entered the Indianapolis 500 for the first time, and he expects to be back.

“I always hear about Parnelli and Mario and Foyt and the list of guys who would be racing dirt stuff full-time and then go and compete in select IndyCar races, especially the Indy 500,” Larson said. “It’s really intriguing to me, that way of racing back then. You don’t really see that much these days. I feel like what I get to do is the closest thing to what they used to do, but even I’m limited a little bit on being able to do that.”

Scott Dixon has collected 58 race wins and six IndyCar championships, statistics that put him right up there with Foyt and Andretti. But with all due respect, he will never achieve the level of hero worship that is showered upon AJ and Mario, on Gurney and Parnelli – or even Kyle Larson. It takes more than numbers when it comes to legacy.