The F1 cars that could have been: Aston Martin DBR4 & Ferguson P99

Aston Martin’s DBR4 meets the Ferguson P99 in a battle of the F1 what-might-have-beens. Jack Phillips discovers two grand prix legends that never were

LEE BRIMBLE

Somewhere in a parallel universe tractor maker Ferguson is held in the same esteem as those other tractor constructors Lamborghini and Porsche. And maybe in that world another tractor builder, Aston Martin owner David Brown, is a Formula 1 champion with a luckless Le Mans squad.

Because in our universe it seems F1 simply doesn’t want tractor makers to succeed.

Their goods were surely good enough: the Ferguson P99 and Aston Martin DBR4 are a pair of F1 racing’s great British what-might-have-beens. But motor sport could never be accused of being fair.

The Aston Martin receiving some fettling in the Silverstone pits on its debut in 1959 as Roy Salvadori sits ready and Carroll Shelby surveys over his shoulder.

There are various mitigating circumstances surrounding both cars’ unfulfilled potential, though the P99 did claim a non-championship grand prix win at Oulton Park. The DBR4 has to settle for being known simply as one of the prettiest of the 1950s F1 cars.

“Their visual differences are cues of an era of racing that was moving at a frantic pace”

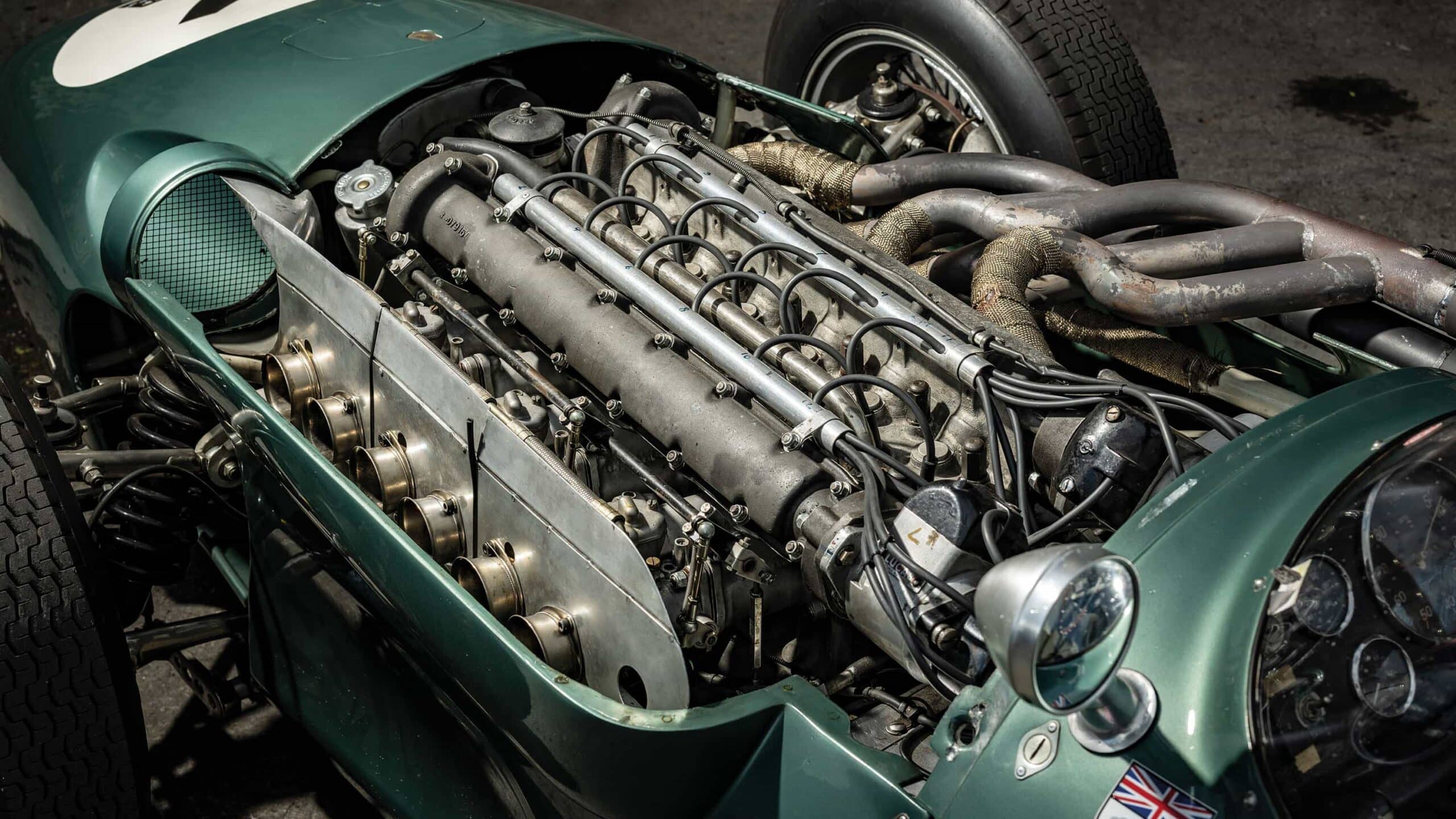

Today, with the sun threatening to break through a damp morning, it upholds those standards as caretaker Martin Greaves of Classic Performance Engineering busily coaxes it noisily and carefully into life. The P99, so happy in the wet, needed less persuading to fire. It could hardly look further apart from the DBR4 – so low and so squat, like a stretched-out 500cc F3 machine.

Stirling Moss in full flight aboard the Ferguson at the 1961 Gold Cup

Their respective visual differences are both cues of, and representative of, an era of grand prix racing that was moving at a frantic pace. Breakthroughs in downforce via wings were still years away, and the engine was just beginning to push rather than drag the car along – although the Cooper T43 preceded the P99 of 1961 by four years and, had the Aston not been mothballed, would have been a contemporary rival for the DBR4.

Both cars were persevering last pillars of the front-engine formula – though for differing reasons. The pioneering four-wheel drive of the Ferguson dictated its engine-first set-up and was able to overcome any subsequent deficiency with the inherent improvement in grip, whereas the conventional Aston was simply late. Not only to the rear-engined light-bulb moment but into daylight at all.

The Aston Martin DBR4 hoped to achieve the sort of success the Le Mans-winning DBR1 later would, but it arrived at the grand prix party too late

Two expensive Aston Martin racing programmes, sports cars and single-seaters, into one flailing manufacturer simply didn’t go, so management plumped for sports cars and was rewarded eventually with a Le Mans victory. Sound reasoning for a sports car marque. Had they gone with the F1 plan for 1958 with the DBR4, itself derived from the Le Mans car and developed from a DB3S, it would have launched into the thick of it. Instead it sat hidden away at the works while a different homegrown, front-engined British Racing Green machine – Vanwall – ruled grands prix, and when finally unleashed it spent 1959 in the shadow of the car that had blocked its exit a year earlier: the DBR1. That came good in June and won Aston Martin Le Mans and later the sports car world championship, although a month earlier the single-seater had threatened to steal its thunder by taking second place at Silverstone’s non-championship International Trophy.

“The two cars are linked by more than just the unrealised potential, and tractors”

Sports car duo Carroll Shelby and Roy Salvadori shared driving duties, and the latter set a new lap record on the way to that second place behind eventual champion Jack Brabham’s Cooper. From there the DBR4 floundered, non-starts, non-finishes and pointless outings largely the order of the day.

Just four cars were built, and ours here was created in the 1980s from leftover factory parts. Geoffrey Marsh, who owned DBR4/1, decided to make use of the various factory parts he had in reserve to recreate DBR4/2 which had been scrapped in period, and when complete it even joined its lead car on some event outings, once with Salvadori and Shelby reunited in the two DBR4s.

Who knows what this pair could have achieved had the Aston raced earlier and Ferguson not lost its founder just as the P99 was getting going

LEE BRIMBLE

The Aston and the Ferguson, both cars cared for by CPE, are linked by more than unrealised potential, and tractors.

After all, a man who was there when Aston Martin claimed its first major post-war international race win was also a leading figure in the rise of the all-wheel-drive Ferguson. Tony Rolt drove the sister car when Feltham won the Spa 24 Hours in 1948 and that same year was working with Harry Ferguson on an all-wheel-drive racer, ‘The Crab’, with Freddie Dixon. Claude Hill, designer of the Aston Martin Le Mans that won at Spa, joined them. Twelve years and nine iterations of the 4WD system later came P99, a high-profile billboard for the technology Ferguson believed would save lives when it reached road cars.

Another Aston Martin man, Jack Fairman, gave the P99 its public debut at Silverstone for the British Empire Trophy, but it was Stirling Moss who showed the car’s potential at Aintree in July. Dipping into the ankle-high cockpit of the Rob Walker-entered car, he lapped three seconds quicker than his 1959 Nürburgring 1000Kms-winning DBR1 team-mate in practice. Out of the race in his Lotus, Moss took over for the final 20-odd laps and put rivals on notice – only to be disqualified for an earlier supposed indiscretion. “It was rather obvious that there are certain teams who do not want the Ferguson to succeed…” reckoned Bill Boddy in Motor Sport, “…and the Ferguson was wheeled away, completely healthy and showing great promise”.

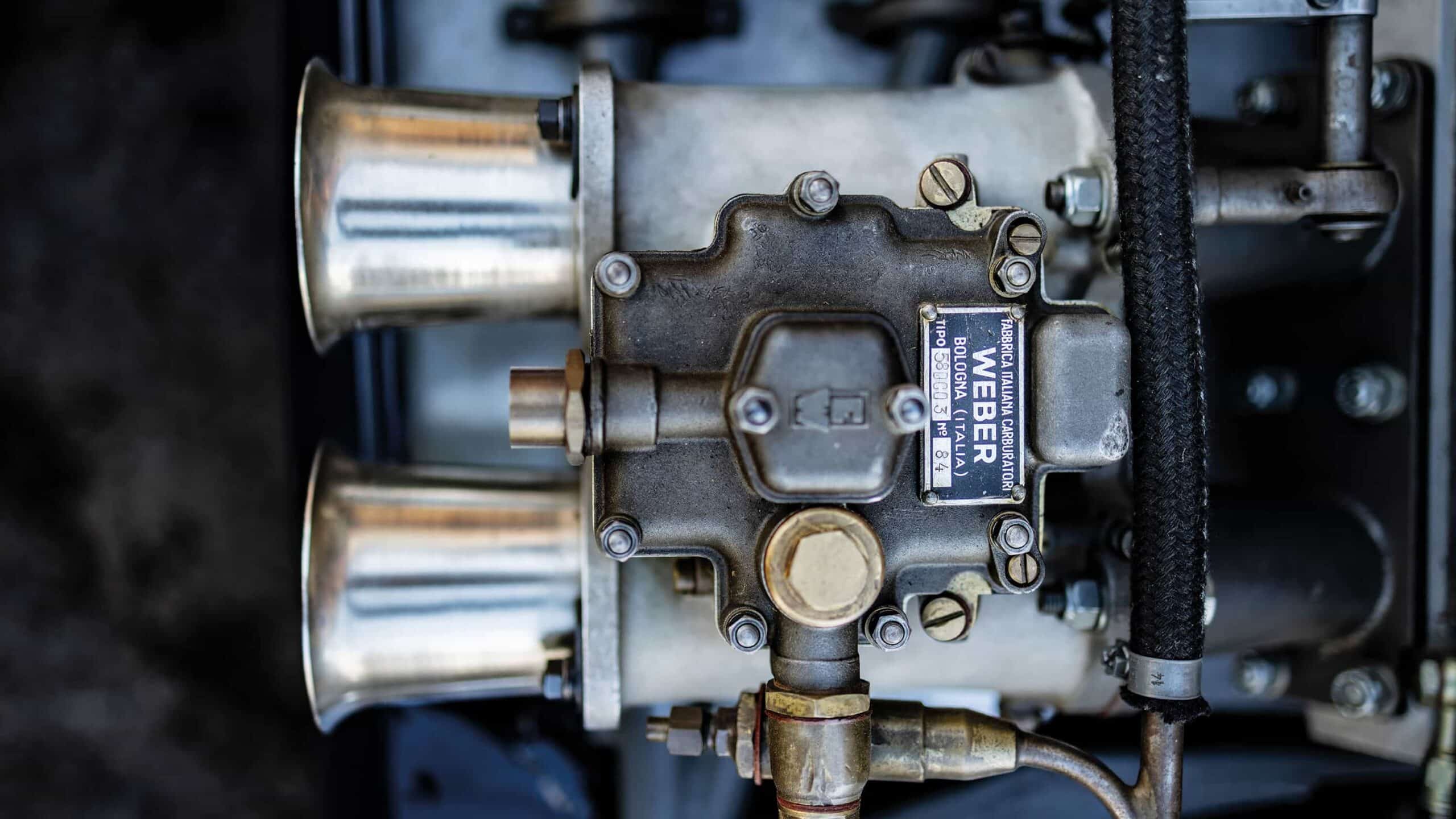

Details of the Aston, which was based partly on the DB3S sports car design

Into autumn the Ferguson made history at Oulton Park for the Gold Cup: “Its unique transmission meant it could out-brake every other car on the circuit and was quite immune from trouble,” reckoned Boddy as rainmaster Moss and the ultimate damp-track F1 car coasted clear, initial first-gear start problems a distant memory. “There should be plenty of wealthy enthusiasts anxious to buy the production Ferguson [road car] when it appears, perhaps in 1963,” WB signed off.

Alas. Harry Ferguson had died 12 months prior, and the project all but concluded after a few more frustrating outings. The Ferguson drifted into the shadows but never out of the family: the 4WD machine showed its paces at Indianapolis, won a British hillclimb title and events in Europe; then Harry’s descendants left it with the Donington Collection until it was recommissioned to go racing – often with Barrie ‘Whizzo’ Williams at the helm.

For the time being, until it finds a new custodian via Duncan Hamilton ROFGO, it remains in the Ferguson extended family because its keeper is Tony Rolt’s son, Stuart. “It was pretty important that I was able to buy it while my father was alive,” he says. “It was a very important car to my dad. He worked for the great Harry Ferguson, a keen motor sport enthusiast, and Harry was persuaded by my dad that the way to demonstrate the advantages of the four-wheel-drive system, which included ABS when there was no ABS, was on a racing car.

The Ferguson’s tight packaging stands out, as does its off-centre driving position

“It was, for him, a big moment winning the Gold Cup – as important to him as winning Le Mans in 1953. They were up against top people like Graham Hill, John Surtees, Jimmy Clark. But my father was quite unsentimental, so when I went to go to buy it I remember him saying to me: ‘What are you doing that for? It’s going to cost you a lot of money!’”

For Stuart it brings back remarkable memories, but he has added his own history to the car, too. His children drove the P99 a day each during the Rob Walker tribute at Goodwood and his son Freddie drove it up the Ollon-Villars hillclimb in Switzerland in 2013 – in the process going one better than young Stuart five decades earlier. “When it won there in 1963, driven by Jo Bonnier, I went with my dad to the prize giving. It was about 15km up, and then of course we had to get down again. I remember sitting in the back of my dad’s estate car behind Jo Bonnier driving the P99 down the hill on a public road, no lights. That is a rather fantastic memory.”

Jack Brabham and Jo Siffert were there that day in 1963, too, but the Ferguson’s permanent grip gave it the edge and won Bonnier over entirely. He smashed his own hill record, and reckoned he could have gone quicker still. So it clearly had pace on its day.

“Had they continued to run and if the conditions had been right,” Rolt says, “I think they could have won grands prix. Who knows what might have happened? At Silverstone in 1961 there was something in the transmission that failed on the startline, and Stirling drove it very quickly at Aintree. It was nice to think that [Ferrari] were so worried that they got the car disqualified. There’s an irony there: in 1954 when my dad was second in the D-type with Duncan [Hamilton], they could have won it had Jaguar protested what was going on in the Ferrari pit when they almost certainly had more mechanics than they were allowed working on the car to get it started. All those years later Ferrari protested the Ferguson.

“I remember Jo Bonnier driving the P99 down the hill on a public road, no lights”

“In the Tasman Series, driven by Innes [Ireland] and Graham [Hill], it was on the mark but it was never clearly faster than everyone else. It was the start of the signs that the additional weight and complication required the right circumstances.

“When the 3-litre formula came in [for 1966] nearly everyone tried all-wheel drive. The disappointment from my father’s point of view, I guess, was that against aerodynamics and big, fat tyres, which didn’t exist during the P99’s time, the advantage of adhesion and grip was being outweighed by the weight and complication of the parts.”

The DBR4 showed promise but made its debut at a time when F1 was shifting to rear-engined cars. Two sixth-place finishes were its best return

LEE BRIMBLE

If the Ferguson had needed the right circumstances, the only circumstances the Aston needed would have been any race track in 1958, if John Wyer is to be believed. Current historic racing is ferocious and fraught, and doesn’t provide a fair test 60 years on, either, because originality comes second to speed. And these are both very original.

Whether the P99 races again is uncertain and will depend on who takes it on. Rolt has been winding down its outings to only demonstration runs on the right occasions. “It’s very precious and the world of historic racing is so competitive that I worry every time I see it on track,” he admits. “The problem with the Ferguson is there’s only one.”

The all-wheel-drive Ferguson was a beauty in the wet, but a complicated drivetrain made it difficult to run

Greaves has certainly been kept busier by the Ferguson than the Aston. “All of the P99 drawings have been lost,” he says. “There’s plenty of history out there, but not technical information so a good deal of it is reverse engineering and starting from scratch. Over the years we’ve manufactured all of the safety-critical stuff: wheels, driveshafts, [inboard] brakes, hubs, gearbox and diff internals. We’ve only done a little on the chassis and the suspension – they’re crack-tested and inspected, but they’re the originals. You have to take a sensible view. We’ve had driveline failures because it just finds the next weakest spot. It is an absolute jewel, beautifully engineered and packaged so well. But it was all done to a weight and size; they got a lot of components into a very small car and they are all working hard.

“The Aston is more traditional. The engine had some issues in period, but it’s a bit more bulletproof. It effectively is a 2½-litre DB3S.”

“The driving position feels odd initially, but then you squeeze the loud pedal and forget about it”

He is also best placed to truly compare and contrast the two from the cockpit. Neither is traditional when it comes to the seating position, and from the outside looking in the Ferguson seems as though it would take the most getting used to. To accommodate the transmission and its satisfying-looking gate, the driver is shuffled to the right rather than staring straight down its nose.

“You don’t actually notice the driving position,” reckons Greaves. “If anything the Aston is more unusual because you’re on the propshaft and have a leg either side of the gearbox tunnel. That feels odd initially, but once you squeeze the loud pedal you forget about that! The Aston is much heavier and clunkier on the gearchange. It’s a transaxle, so there is a big David Brown unit behind, and it sounds like it’s going to break into a million pieces – until it gets warm. Then it starts working better.

Five-speed shift

LEE BRIMBLE

“The Ferguson has a quick change, nice and light. Years ago we put a new clutch in and so I had to go up to the test track here at Bicester to make sure it was functioning correctly and the thing is just unbelievable. You can hardly get it to wheelspin – it just grips and goes. It’s something else. And when you sit in the Ferguson, the history just exudes from every chassis tube.”

It’s a shame that history can’t tell us exactly how far the P99 would have gone, and just how good the Aston Martin might have been. Both might have proved world beaters but for ‘shoulda, woulda, coulda’. They were out of time.

The P99 was the first four-wheel-drive car to win an F1 race.

LEE BRIMBLE