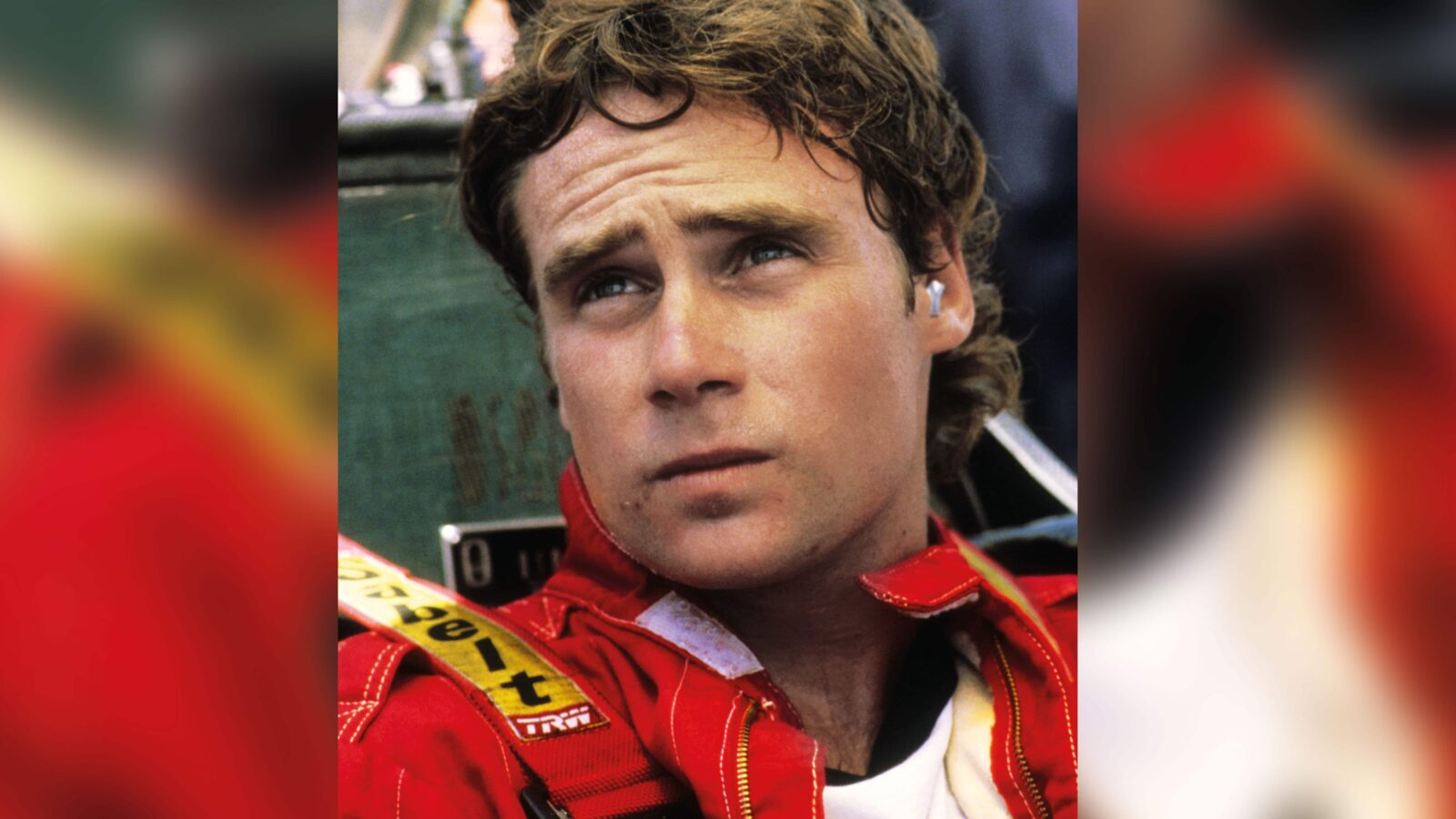

Allen Berg: The Motor Sport Interview

His time as a 1980s Formula 1 backmarker was all too brief, yet there was so much more to the colourful racing life of Allen Berg, who is still carving his own niche today

DPPI

Forty years ago, a 21-year-old unknown from Alberta, Canada, pitched up in England with dreams of racing in Formula 1. Allen Berg made it – just – starting nine grands prix for Italian minnow Osella in 1986, before the dream crumbled. Still, Berg found his own path to racing success as he headed down Mexico way to forge an unlikely life and career away from the mainstream – and on his own terms. Formula 2 champion in 1993, he was a frontrunner in Mexico’s well-funded Formula 3 series in the mid-1990s and capped his time south of the border with a Panamerican Indy Lights title at the age of 40. He then briefly ran a Formula Atlantic team in the US.

“Sometimes Eddie Jordan could be very hard on me, at times patient“

Today, at 62, Berg has settled happily in Buford, a quaint corner of Georgia, and runs a successful racing school business at American grandee tracks Laguna Seca and Road Atlanta. He has also set his 16-year-old son Alex Berg on his own path to a possible racing future. Alex is racing in US F4 this year and has ambitions to follow his old man’s example by heading to the UK for 2024. So a chip off the old block? Perhaps – but with greater confidence than his modest father ever showed. We caught up with Allen on a call to his race shop, based near Road Atlanta.

Motor Sport: Our readers might remember you for your two seasons in British F3 in 1983/84. How did motor sport start for you?

AB: I was always a fan. Growing up I always used to watch ABC Wide World of Sports in Canada. We only had two channels back then in the mid-1960s. There would be a black and white report from the Nürburgring or something. It was always a curiosity, this sort of racing, because it seemed unachievable. There was IndyCar and NASCAR, but I found that unappealing. But road racing, driving these sleek state-of-the-art race cars, really appealed. There was no internet back then, so all you had was Road & Track with reports written by Rob Walker, and I always dreamed about this world. When I had a chance to get a go-kart with my dad, paid partly by my paper round, we raced around western Canada when I was about 15. We both loved racing and went to the Long Beach GP in 1977. That was inspiring. I did well in karts and my parents helped me into Formula Ford.

Eddie Jordan with Allen Berg, right, at a party in 1983. It was a fun experience with that team

Sutton Images

Before British F3, you raced in New Zealand and Australia, didn’t you?

AB: I got picked up by a couple of teams, did some instructing at racing schools. I did quite well and was able to move into Formula Atlantic in North America. Then I had an invitation to race in New Zealand because they had Canadian-Pacific sponsorship and wanted a Canadian driver. That was for the Tasman Series [aka Formula Pacific] and I won it – the same series that Graham Hill, Jimmy Clark and Jackie Stewart raced in. At one point I was handled by Gilles Villeneuve’s manager, and he made an introduction to Michel Koenig, the publisher of Grand Prix International magazine. Every year they would support a driver in British F3. At the Canadian GP I was introduced to him, he saw me drive and gave me an opportunity. That got me to England.

What did it mean to you to get the chance to race in England?

AB: It was a dream that slowly became a reality. I always had a vision in my mind of what it would be like to be on an F1 grid. And if you want to race in F1 you have got to go to Europe, which is why I’m hoping my son Alex will head over next year. That’s where you cut your teeth. I had raced for seven years prior to that. I learnt more in my first year in British F3 than in the previous seven.

British F3 action at Thruxton in 1983, where Berg leads Johnny Dumfries. Johnny would make it to F1 in 1986, as would Berg

What was it like arriving in England to go racing in 1983?

AB: First of all it was very cold, literally and figuratively. The British, as you know, are very reserved. I started with another team, then transitioned across to Eddie Jordan’s team with a lot of Irish and Kiwis with outgoing personalities. They embraced me and made me feel better. But coming to England having won in New Zealand and Australia, suddenly I was a nobody until I’d proven myself. It was tough. In those days in England there were four TV channels – BBC1, BBC2, ITV and Channel 4, and most of the time they were either showing darts, snooker, cricket or football. There was no internet. The adversity was not only getting over there, but also earning your stripes and being treated with respect, earning results and gaining the support of a team around you. It’s a culture shock and you just have to fight your way through. Also when Johnny Dumfries, Andrew Gilbert-Scott or Martin Brundle had a bad race they went back to their families. I went back to my apartment to brood for two weeks until the next race.

Eddie Jordan is not reserved, as you know! What was it like driving for him?

AB: An amazing experience. Eddie had wit and was a sharp businessman. Some people didn’t like him, but he got the job done and got his team to F1. He helped a lot of drivers along the way including Martin Brundle and Jean Alesi, and gave Michael Schumacher his first chance in F1. I wasn’t at the level of a Schumacher, of course, but he did support me and it was a lot of fun with Eddie. Sometimes he could be very hard on me, at times very patient. A great experience. Some of the Irish mechanics were tough guys and scared me a little. Walking into the shop you didn’t know whether they would want a cup of tea with you or to get into a fist-fight. There were some pretty intimidating characters.

Certainly no shame in being third here, as Ayrton Senna and Martin Brundle claimed the top two spots at Silverstone in 1983

Sutton Images

You were team-mate to Brundle, while Ayrton Senna was at West Surrey Racing. What were they like?

AB: Incredibly intelligent, both of them. Adaptable, thinking on their feet. Martin could draw on set-up information, had a great memory for retaining it and was unflappable. Senna was an incredibly driven man. He faced a lot of adversity and I saw some of the rivalry between a British and Brazilian driver, the public cheering on Martin and booing him. He managed all of that. At Thruxton one time I was running fifth and up the hill from Church we would all fan out on the way to the chicane. I spun, got going again and finished the race. Afterwards we crossed paths through the paddock and Ayrton asked, “What happened on the first lap? I saw you were fifth and then we came out of the chicane and you weren’t there any more.” I made up some flimsy excuse. You know how small those wing mirrors are on the side of a formula race car, but he knew what position I was in and the moment I was gone.

You stayed for a second year and finished runner-up to Johnny Dumfries, didn’t you?

AB: We were running on a very tight budget that year, virtually race to race. Johnny was a very talented driver with backing from Racing for Britain, BP and had factory Volkswagen motors, so his equipment was immaculate. So was Eddie’s but we had Toyota motors and the Volkswagens had a bit of an edge in terms of power, or at least Johnny’s did. I finished second many times that year and he had too much pace. He beat me and everyone else on most occasions. We had second in the championship but it was frustrating because my goal was to win. Back in those days if you won the British F3 championship, you weren’t guaranteed a ride but you’d most likely get an opportunity in F1. Which he did [with Lotus in 1986], and then I eventually did too.

But it wasn’t a straight path to Formula 1 for you, was it?

AB: No. After my second F3 season I tested with Arrows, got my superlicence with the assistance of Bernie Ecclestone. Gilles Villeneuve had died a few years before and they wanted to have a Canadian. I did a test, it went well but at that point with Tyrrell and Arrows it was about $1m to race, which was significant money. F1 was not very understood in Canada and still isn’t very much in western Canada. It’s a country all about [ice] hockey. I would talk to sponsors about the global reach of F1, the TV audience, but I was only a 23-year-old kid trying to approach companies in Toronto. I wasn’t able to break those barriers. Some said to me, “If you get into F1, come and talk to us.”

I ended up getting an offer to race in Mexico for a year and get paid to drive race cars. I had nothing else going on and when I got down there I realised there was a lot of support for motor sport in Mexico. There was Marlboro, Telmex, Corona beer, Montana cigarettes, Coca-Cola – big companies. They had national series that were televised live and all the teams had big sponsors, and the drivers all made money. By that time I’d lost touch with Grand Prix International magazine – it had shut down. But I bumped into Michel in a hotel in Toronto and he started helping me out again. He was still connected to F1.

Receiving a pep-talk ahead of another Osella battle.

SUTTON IMAGES

So how did you end up at Osella?

AB: When Marc Surer was injured in a rally crash, the Arrows seat became vacant. Christian Danner was a friend of mine, we’d met doing the Tasman series, and he moved across from Osella. I was in Montréal, so was Michel and we were able to put together a deal at the end of the Canadian GP. This was a chance to race in the 10 remaining grands prix of 1986, starting at the US GP in Detroit. They basically took Christian’s contract, whited out his name and his sponsorship dollars and put mine in. The deposit I needed, we didn’t have much time, and we didn’t have sponsors immediately to support it – so my grandmother fronted me $25,000 out of her will for that initial payment to Osella. The contract was all in Italian – I wish I had a copy now. I don’t know what it said, but I wanted to be an F1 driver, so I signed.

Osella at the 1986 Mexican Grand Prix. This would be one of just four grands prix he’d finish

Getty Images

And you were pitched straight in?

AB: My first time driving the Osella was actually the first practice session in Detroit that week. A vivid memory. Only my mechanics spoke English and so did the race engineer. Enzo Osella spoke Spanish and Italian and I’d learnt some Spanish. As I walked down the pitlane Ken Tyrrell put his arm around me and said, ‘Allen, the best thing you can do this weekend is keep it on the island.’ And I did. I qualified 25th out of 26. My first session was just staying out of the way, learning the track and getting the feel for this car, its power and turbo lag. It was a 950bhp, 1500lb race car I’d never driven, surrounded by walls and barriers with no room for error. So I was taking Ken’s advice!

“I spent my time racing with one eye on the rear- view mirror”

How did it feel to be an F1 driver?

AB: The drivers’ meeting was where it really hit home. It was in a small portable trailer and my team said you’ve got to get there early because if you are late they fine you and we don’t want that. So I got there early and sat down. Then Johnny Dumfries came in, who I knew from F3. We had been adversaries, but now we were kindred spirits because he was struggling in F1 at that time. Then everyone started filing in, the legends of F1: Alain Prost, Keke Rosberg, Nelson Piquet, Alan Jones. Six [present or future] world champions in this confined trailer. It felt good to be there. Then Jacques Laffite rolled up a piece of paper into a ball and threw it. It bounced off Johnny’s nose, everyone laughed and Johnny went red.

Berg competed in just nine grands prix with Osella. It should have been 10 but he was replaced by the paying Alex Caffi at Monza

Alamy

But Osella was a tough gig. How did you cope what that?

AB: It was a very tough year because we had zero testing and you could see the other cars developing, they just got faster. We had an extremely low budget. In terms of putting together the sponsorship I was in arrears all the time. They took me out of the car for one race, the Italian GP, and put Alex Caffi in the car because he had the sponsorship for that race. But they put me back for the remainder of the year. Enzo said he wanted to run me, but I had to pay and if I didn’t I’d never race in F1 again. During that time the Labatt Canadian beer company came on board with us and supported my racing. They paid off what I owed, so I did the last three races of the year to complete the season.

What was it like being an F1 backmarker?

AB: I spent my time racing with one eye on the rear-view mirror. My car in qualifying had 950bhp, but some of the others had upwards of 1300. In Mexico and Australia we had one spare motor between two cars, so my practice was limited to just six laps to learn the track. Not the greatest environment, but you make do with what you got. They wanted me to run, to start and finish to gain prize money, which was key for them. The most stressful points of the weekend was when the frontrunners came to lap me. I vividly remember Nelson Piquet going after Eliseo Salazar [at Hockenheim in 1982], and I didn’t ever want to be in that situation. It was always very dirty off line and when you pull over it’s still a 950bhp race car on a dirty track. Looking in those tiny mirrors and trying not to get in their way was very stressful.

Chaos at Brands Hatch in 1986. Berg’s Osella was caught in the multi-car tangle that would end the career of Jacques Laffite, who would break both legs. Zakspeed driver Jonathan Palmer, who now owns Brands Hatch, gave him medical assistance

McKLEIN

You were caught up in the first corner pile-up at the British GP that finished Laffite’s career. What are your memories of that?

AB: The thing I remember most was not so much that, but a practice crash earlier in the weekend. It was my third grand prix and finally I got to a track I knew. In first practice I was really comfortable in the car at Brands Hatch and I performed well, certainly against my team-mate. I went out the next morning and binned the car at Druids. I never knew what happened. The Pirelli tyres were very slick. I was holding the speed of the car in second gear, then all of a sudden the rear tyres spun up, the car went sideways and I went into the barrier. That moment changed my F1 career – it was hugely disappointing. I blame myself. One of two things happened: either a half-shaft broke and pitched it, or where I was holding the throttle was just where the turbo kicked in. Walking back to the pits they were showing the accident on repeat on a screen. It was heartbreaking. The car was damaged quite badly and it took a lot of my self-confidence. The accident in the race was just the end to a crummy weekend.

You never raced in F1 again after 1986. What happened?

AB: I’m not very proud of it, but I became influenced by this other Canadian group that promised a lot of great things but didn’t deliver on any of them. Labatt had discussions with six different teams, they had an interest in supporting me the following year. Then the Canadian GP got cancelled because Molson had rights to the GP and Labatt had the rights to the track – or vice-versa. The 1987 race got cancelled and Labatt lost interest in supporting me. At least that’s the version I got. I was in Canada for a while, then moved back to Europe and did some Group C and DTM. After a year with a small privateer in DTM, the sponsor Tic Tac pulled out. Then I had an offer to race for Marlboro in Mexico. I went down there to see what it was all about. They picked me up at the airport and took me straight down town to a hotel where there was a press conference announcing me as their new driver. I didn’t have anything signed. But it was big-time racing. In a Marlboro series I was the Marlboro driver. How could I say no to that? I was getting paid pretty well to drive.

Berg’s privateer DTM BMW entry in 1991.

McKLEIN

It sounded exotic, racing in Mexican F2.

AB: I won 25% of the races I entered. It had ups and downs, and I made a few mistakes along the way in terms of my career decisions. But ultimately in my last year of racing I was able to form my own team. I was getting towards my forties and thought there was more to life than driving race cars, so I became the manager of this four-car team. It was my last year, I considered myself the fourth-most important driver, yet it turned out to be my best year of racing ever. In nine Panamerican Indy Lights races I think I won five. I won the last ever race I entered and clinched the drivers’ and teams’ championship with my own team. They were old Indy Lights chassis with 475bhp Chevy engines, so fast cars.

You raced in Mexico from 1992 until 2001?

AB: I spent too many years in Mexico and took myself out of the mainstream. I’d go to races in the US and they’d only remember me from years before. Some teams talked about me bringing sponsorship, but in Mexico I was getting paid. I wasn’t making millions, but it was an upper level executive’s salary and I had a good lifestyle down there. Why pay a team when I’m earning a salary? Also as a result I met my wife, who is Mexican, we’ve had my son Alex, so that’s the way destiny goes. And I was lucky enough to never be seriously hurt as a driver.

In a Porsche 962C in 1987.

Alamy

Today you run racing schools at Laguna Seca and Road Atlanta. The overheads must be high. What are the challenges?

AB: The way I see it, people pay a lot of money and they come with high expectations to these iconic race tracks and they travel long distances, regularly from overseas. It’s my goal to provide them with an enjoyable experience that is safe. A lot of it is protecting drivers from themselves. We had to learn to manage it. Have you ever gone deep-sea fishing? You get up at 6am, usually in a nice place, you go out in a boat all day and you might get a strike on the line for only 15 minutes. But you still have a great time all day. I tell everyone at the school that it’s almost assured that when the driver is in the car they are going to love it. What’s more important is the time out of the cars, that they are treated well. We’ve expanded beyond racing schools and do driver training programmes for a lot of manufacturers now, and that’s becoming a big part of what we do. We’re branching out.

Berg enjoyed success in Mexico after F1. Here he celebrates victory in the 2001 Indy Lights Panamericana series, shortly before his retirement from driving

MEXSPORT

It’s 40 years since you arrived in England to race in British F3. Are you proud of where it took you?

AB: I’ve always believed you are only as good as your last race. I try not to think of the past very much. But you’re talking about it being 40 years since my F3 days. This past winter I got to come back to the UK and go to the Autosport Show and take Alex. Then we went to London to meet some of my old friends, which was fabulous. It was touching that people remembered me.

“The accident at Brands was the end to a crummy weekend“

So Alex could be over here racing soon?

AB: Hopefully. He’s working on incredible things for a 16-year-old, things I was never able to come up with. I was very quiet, reserved and timid. One thing we’ve tried to do in raising Alex is for him to be self-confident, to be able to go out and learn how not to be intimidated in situations. It’s down to him to find the budget. Obviously I try to help him every single day, how to do things right and move it forward, but he’s got some pretty unique opportunities to support his racing career.

I’ve talked to you a lot about my career, but I can assure you once the interview ends all I will be thinking about is how to keep this crazy business going!

The racing school business