Courage LMP2 car that saved my career

Some 20 years ago, Sam Hancock was a single-seater graduate looking for a career route. Courage threw him a lifeline with its LMP2, and now he’s reunited with it

Life has a funny way of marking the passage of time. Discovering that cars I once raced contemporarily are now eligible for historic series is certainly an effective reminder of my advancing years! Fortunately, the silver lining is that I get to reunite with some incredible machinery that I had long assumed I’d never experience again.

Such has been the case recently with the 2004 Courage C65 LMP2 that I drove for the works team nearly 20 years ago, both at Le Mans and in the European-based Le Mans Endurance Series. Given the state of my defunct career at the start of that season, you’d never have imagined that just a few months later I’d share three LMES class wins and the championship title with my co-drivers, let alone have briefly led the LMP2 category at Le Mans in a car that qualified on pole position in its class. It really was a dream season and, given the momentum that followed, it’s not a stretch to say that the car responsible – chassis C60-No9 – possibly saved my career.

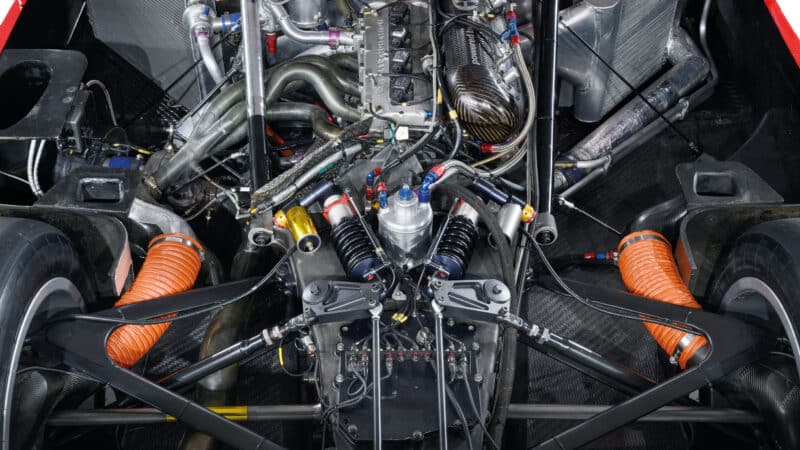

The 2-litre AER engine was a new addition to the car for 2004, but failed in the race. Now it’s fully refreshed

Just weeks before the 2004 edition of the Le Mans 24 Hours I was done. No drive, no sponsors and few prospects of either appearing on the horizon. After a few scattered wins in junior single-seaters, a brief foray into sport cars with Kremer Racing, and a forgettable Le Mans debut in a GT2-class Ferrari, it was hard to see where the next opportunity might come from. I’d had plenty of chances and it just wasn’t happening.

Earning a living that summer by flogging motor sport hospitality packages with friend and former F3000 team owner Vincent Franceschini, I grew frustrated one morning a fortnight or so before Le Mans that I couldn’t secure the all-access pit passes my clients demanded and risked losing the sale.

Period stickers add to the memories.

“I wouldn’t have any trouble getting pit passes if I had a drive!” I remember moaning to Vincent. “Well let’s try to find you one then,” came the totally serious and utterly unexpected response from Vincent.

“The level of downforce through quicker turns begged me to brake less, throttle more”

Slipping seamlessly into an undiscussed managerial role he hit the phones, calling every team on the entry list, well aware that seats sometimes open up when drivers’ funding, or talent, fail to meet expectations at the official test, two weeks before Le Mans.

Fortunately my CV, while not exceptional, was at least credible: I had come out of single-seaters with a few ‘pots’, had experience of prototypes and knew the Circuit de La Sarthe. It was a long shot, but he was taking it.

Long-haired Sam in 2004 with Courage team-mates Jean-Marc Gounon, left, and Alexander Frei

Astonishingly, the call to the works Courage equipe, then based inside the circuit’s Technoparc, found traction. One had the impression that Yves Courage’s team was extremely short of cash having invested every dime into its then-new LMP2, so it offered me a seat on the proviso that I could bring some sponsorship. Naturally the number suggested started at an unthinkable level, so when I called back a few days later with a counter-proposal that moved the decimal place significantly in my favour, the last thing I expected was an agreement. But the team must have really needed the money because I was on the next ferry to Le Havre.

Having missed the official test, being thrown straight into race week was far from ideal as I was a little rusty. Fortunately, Courage had built a fabulous car that I just clicked with right away. More than any I had experienced before, it just felt easy – welded to the road, with a level of downforce in the quicker turns that just begged me to brake less, throttle more. In fact I distinctly remember the light-bulb moment during practice when I figured out how to drive the car: hurtling into the relatively fast Forest Esses at the bottom of the sweeping downhill approach, I realised that if I just got off the bloody brake pedal, rolled considerably more speed into the entry, the car would float perfectly into a precise apex rather than resist my steering input. If I then folded in some throttle, the rear diffuser would hug the asphalt a little tighter and catapult the car out of the corner, unflustered by the crested right-hander that followed. It felt like driving the future – and I loved it.

This revelation unlocked the C65 for me and, as the confidence grew I was able to compare well with my team-mate, Jean-Marc Gounon, who remains one of the most naturally talented drivers I’ve ever had the mildly depressing privilege to witness.

The small steering wheel and tight cockpit didn’t leave taller drivers like Sam much space, so called for some boot modification

I remember him coming on the radio while conducting his own laps in qualifying. Our team-mate Alexander Frei and I had had very limited running and Jean-Marc was trying to help shortcut our learning curves by talking us around the lap, live, as he drove it.

I’ll never forget his serene delivery – as though kicked back on a sun-lounger: “OK, so the braking point for the first chicane is… (brief pause while the engine sings the first couple of downshifts) …120metres.” Then a short delay while he inhaled the next section of the famous Mulsanne: “OK, second chicane (‘blip blip’ from the downshifts) you can brake at 100 metres, more grip here, use fourth on entry – blip – third for the right.” It was extraordinary, he’d not even finished braking or downshifting and still he was able to communicate in perfect detail where he deemed the absolute limits of the car to be.

The Courage at Le Mans in 2004

Jean-Marc was a qualifying maestro, and to say that he blitzed it that year would be a gross understatement. Out of nowhere he pulled a lap that was 10 – yes, 10 – seconds faster than anyone in our class and quicker even than several LMP1s. I have no doubt that the engine was turned up to 11 and that Michelin may have afforded its compatriots some special rubber, but this was nonetheless an exceptional performance and seemed to steal morale from our rivals and feed it to the famished Courage squad.

Pre-race family photo

The team was buzzing, Yves Courage in particular because he knew that his C65 would now sell and that his company’s financial future would likely be secured. Jean-Marc later told me that he too was aware of the lap’s importance and that he therefore left nothing on the table, straight-lining the final chicane, with the car briefly airborne.

After the excitement of qualifying, the race sadly didn’t go to plan. The decision to run AER’s 2-litre four-cylinder turbocharged engine in place of the naturally aspirated JPX V6 had only been taken in the few days since the official test and its installation remained untested over long distances. I forget how many hours we lasted before retirement.

Fortunately it held on long enough for the car to lead the class and, crucially, for the team to see enough of my performance to invite me to remain for the rest of the season.

Three of the four-round Le Mans Endurance Series remained: Nürburgring, Silverstone and Spa, each 1000Kms. While not the most populous category that year, we nonetheless won our class at all three events and sealed the LMP2 championship.

Remarkably, chassis C60-No9 then went on to have an incredible second chapter of its career with American squad Miracle Motorsports. Not only did it take class honours at Sebring in addition to further ALMS class wins at Lime Rock and Road America, but it also returned to La Sarthe twice, finishing third in class and 14th overall in 2006.

Paolo Catone’s design has stood the test of time. He would later go on to pen Peugeot’s Le Mans-winning 908

In the near-two decades since, I hadn’t given the car much thought until a text message arrived in 2021 from a friend alerting me to the fact that it was still in America, in private ownership and was potentially for sale. When further investigation revealed the car to be in good health and accompanied by much of its original spares package, I knew I had to have it. Unfortunately I also knew that I couldn’t afford it! Teaming up with members of my family we managed, over many months of extended negotiations, to eventually agree a purchase. The car was being recommissioned, not a process we wanted to interrupt, so we had to be patient until we could finally ship the car here to the UK earlier this year.

Hancock helped the Courage works team to the LMP2 title in 2004, rewarding its gamble on taking him for Le Mans

With further work required to get it up to a truly race-ready standard, we entrusted the preparation to Oli Cable’s impressive Pursuit Racing outfit in Oxfordshire. Oli and his team worked their magic and, by February, the car was finally ready to be driven again.

“I had to keep my mutilated race boots hidden from the officials”

After its restoration Sam is now selling Courage C60-No.9. It is now available for sale. Visit www.samhancock.com

An initial straight-line shakedown on the runway at nearby Turweston airfield was mired by the typically British weather, but thick fog, freezing conditions and constant drizzle wasn’t going to dampen our enthusiasm and, on slick tyres (the only set we had), my brother, Ollie, and I spent the morning wheel-spinning up and down conducting various function checks. I’d love to tell you that the memories came flooding back on a wave of nostalgia, but the conditions were far from conducive and, while still wearing its Miracle colours, it didn’t really feel like ‘my’ car.

Tempting as it was to leave the Miracle livery untouched, we ultimately decided to return the car to its original works-team colours from 2004 – and, for me at least, this changed everything. As soon as I laid eyes upon the beautifully detailed new look I felt instantly connected to it again. Fortunately, very little had been changed in the cockpit, with most of the original instruments, switches and labels remaining exactly as they had been 19 years earlier. So when I finally did get to drive the car in anger again at Donington recently, in a proper test, in dry weather, the years at last started rolling back. It was exactly as I remember: incredibly light steering, lithe and agile in the tighter corners, and just effortless in the quick ones.

Gounon was a qualifying master, and shattered the LMP2 competition to snatch pole at Le Mans in 2004

That AER P-07 engine felt impressive too, more powerful than I recall although that is almost certainly just my imagination because with the correct 43mm restrictor fitted, we still have about 500bhp, which would match output of the period. Getting used to the braking points again took a few laps, as with huge carbon discs and a little over 750kg of mass to decelerate you can often brake even later than LMP1 cars, which takes some mental recalibration! And, as the tip of my size-11 race boots rubbed against the steering column while doing so, I also remembered why I had to chop the toes off them all those years ago and keep my mutilated boots away from the prying eyes of any officials!

Some kind folk have asked if I still fit in the original seat. Fortunately it’s long since disappeared so I guess we’ll never know, although let’s just say that I shan’t be dusting off the old race suit in a hurry.

The C65 was designed by Paolo Catone, and a derivative of his successful C60 LMP900. To me, it is a pretty car, emblematic of its era, and already ageing gracefully. That it still feels so modern to drive, so current in just about every element of its handling and performance, is a testimony to Paolo and to the entire design team at Courage. While I personally love the period-correct, lever-operated sequential gear change, I dare say that if it was fitted with paddles, as would’ve been the case in the following years, it would be hard to distinguish from cars of distinctly younger vintage. Did it save my career? Yes, almost certainly.