Star Turn: Mallory Park

On Whit Monday 1962 Mallory Park attracted the finest F1 teams and drivers for the lucrative International 2000 Guineas race. Sixty years on, Simon Arron is at the anniversary reunion to submerse in a cacophony of Climax power units

They are rarely mentioned in the same breath, but Mallory Park and Formula 1 are by no means strangers. The circuit was a staple on the British Formula 1 Championship calendar during its three-season zenith, 1978-1980, hosting two rounds annually. At the time it seemed wholesome, noisy fun as recent, second-hand grand prix cars hurtled around in little more than 40 seconds. Nobody batted an eyelid that the track had precious little in the way of pit facilities… or even less in terms of run-off. It had – and still has – a magnificent café, which surely mattered more…

Leading grand prix teams very occasionally tested there – using the hairpin to evaluate low-speed set-ups – and in slightly more recent times F1 cast-offs have appeared in the EuroBOSS Formula Libre series (later Boss GP, which nowadays operates on slightly longer circuits in mainland Europe). During one such race in 1997, Finn Johan Rajamäki lapped the circuit in 38.23sec (127.12mph) at the wheel of his Footwork FA13, a five-year-old F1 chassis strapped to a Judd V10.

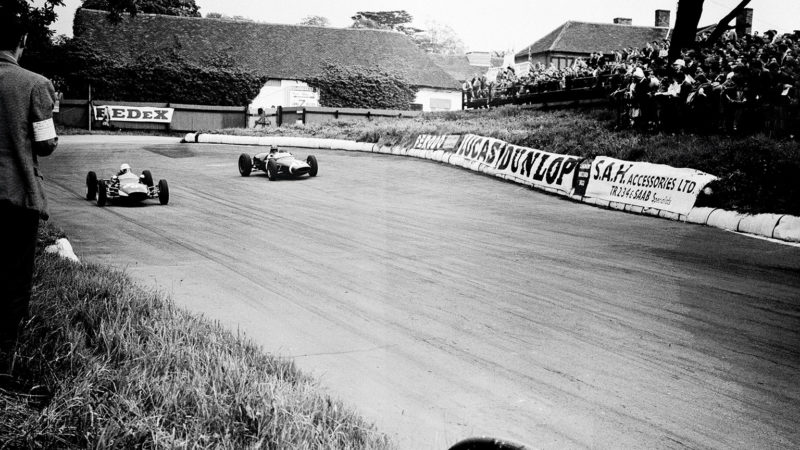

John Rhodes in Bob Gerard Racing’s Cooper T59

Formula 1 cars graced some early Libre events at the circuit, too, but only once has Mallory Park hosted a contemporary F1 race that attracted the leading stars of the day – and that was 60 years ago. June 11, 1962 has an added distinction, for it was also the last time two F1 races took place in the same country on the same day. Innes Ireland (Lotus 24) beat a field that had some strength but not too much depth to win the Crystal Palace Trophy, while the line-up at Mallory had greater past and future pedigree (if only one more car, 13 rather than 12). Double world champion Jack Brabham was present, as were three imminent successors (Graham Hill, Jim Clark, John Surtees) and other notables such as Masten Gregory, Jo Bonnier and Mike Parkes, who followed up his fourth place in the F1 race by taking his Ferrari 250 GTO to victory in the supporting GT final, ahead of Hill (Jaguar E-type) and Surtees (250 GTO). The Formula Junior race was won by Pete Ryan, one of the sport’s great might-have-been stories (Motor Sport, June 2001). Sadly, it would also be one of the rapid US-born Canadian’s final starts; he was killed three weekends later while battling for the lead in a Junior heat at Reims.

It’s possible that the leading teams and drivers were drawn to Mallory less by the prospect of a hearty breakfast than they were by one of the UK’s biggest prize funds of the season: immediately after the race the winner would receive 2000 guineas (£2100, the equivalent of almost £50,000 today), with £500 and £300 to the other podium finishers. The victor would also take home the Coventry Cathedral Festival Award, a silver salver presented by the wife of Leonard Pelham Lee, chairman of Coventry Climax (whose engines powered all but three of the field). A Ferrari V6 was supposed to increase the sonic variety, but although a car appeared on the entry list for a driver “to be nominated”, this was withdrawn.

Brabham was among a stellar line up at Mallory Park – here photographed during the race

Despite its stature, the International 2000 Guineas was run by respected race organiser the Nottingham Sports Car Club rather than any of the major national bodies, and its pre-race publicity campaign proved effective. As Motor Sport reported somewhat vaguely in its July 1962 issue, spectator attendance was “variously estimated at between 30,000 and 50,000”, each having paid £1 in anticipation of seeing “a works Ferrari doing battle with the British cars”.

Race winner John Surtees would receive a silver salver presented by the wife of Coventry Climax chairman Leonard Pelham Lee

Jim Clark qualified his Lotus 25 on pole in 51.0sec and lined up on the left-hand-side of the 4-3-4 grid, alongside Brabham (in a Lotus 24, though he’d give his eponymous BT3 its world championship debut soon afterwards at the Nürburgring), Hill (the BRM team leader guesting in Rob Walker’s Lotus 18/21) and Surtees (Bowmaker Lola Mk4). And if that pole time sounds modest, it was – a by-product of the 1.5-litre engines regulations imposed one year beforehand. In practice, fastest Formula Junior qualifier Peter Arundell posted a time good enough for the front row of the F1 grid. By the late 1980s, the quickest Formula Ford drivers would be lapping the same track in the mid-48sec bracket.

Surtees made the best start from the outside of the front row to take a lead he would never lose and score what would be Lola’s only F1 victory. Jim Clark was beginning to recover from a slow start that dropped him initially to fifth, but fading oil pressure obliged the Scot to pit and eventually retire. According to Motor Sport reporter Mike Twite, Clark’s departure “left the race in a rather dreary state as no one looked like catching anyone else, except Parkes who got past Gregory for fourth place on lap 28. In fact, from lap 28 to the finish on lap 75 there was only one positional change, when [Tony] Shelly passed [Carel Godin] de Beaufort for eighth on lap 37. Surtees gradually increased his lead over Brabham until at the finish he was 18sec in front, with Graham Hill a steady third in his first Lotus drive for some time.”

GT final on the same day, with Mike Parkes leading in a Ferrari 250 GTO

The race provided the front cover photograph for the June 15 edition of Autosport, whose report – written by magazine founder Gregor Grant – was a touch more upbeat. “The Whit Monday crowds that rolled up to Mallory Park certainly had their money’s worth,” he wrote. “Every race was hotly contested, lap records tumbled and John Surtees gave an exhibition of driving to win the 2000 Guineas International event, which was a sheer delight to watch…” It’s fair to say Twite hadn’t been quite so impressed. Signing off, he wrote, “Although the racing went smoothly enough and the crowd got a good view without the circuit owners haying to pay for grandstands, the organisation as far as the press was concerned was amateurish in the extreme and some of the gate marshals appeared to be village idiots specially drafted in to stop anyone going about their lawful business. The official results were inaccurate, which was not so serious for those who had been taking notice, but members of the daily press do not expect to have to correct official results before telephoning their offices. Perhaps by next year the Nottingham Sports Car Club and the Mallory Park people will have sorted out these problems and be able to run an international event properly.”

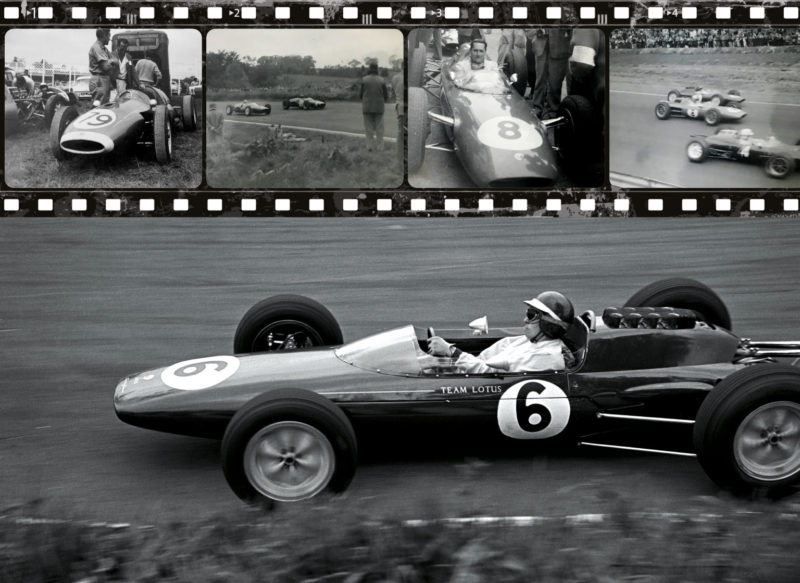

Jack Brabham took second in the F1 race in this actual Lotus

There never would be a ‘next year’ for contemporary Formula 1, of course, but the fact such an event happened at all remains a cause worthy of celebration. That’s why, a few days beyond the 60th anniversary, Motor Sport was present at Mallory Park for a small but significant reunion that brought together three of the cars from that race – the winning Lola, Brabham’s Lotus 24, Clark’s pole-sitting 25 and a Cooper T56 redolent of the period (albeit a non-runner on the day, as its Colotti gearbox was being rebuilt). The man tending the Cooper, Mick Mobberley, has worked on cars such as this since they were new; his first race on duty was the 1961 British GP at Aintree.

Ironically, given that it had run faultlessly en route to victory in ’62, the Lola had been slightly bothersome prior to the photo shoot. “These cars should be quite straightforward,” says Robert Boughton, who was charged with the car’s preparation and describes himself as “a self-employed spannerman”, albeit one who also sometimes competes in historic Formula 1. “We’re fighting the fuel system at the moment and have no idea why. It will run cleanly for about half an hour and then starts to pick up air.”

Not an issue, fortunately, for a few laps behind a camera car. Mark Quelch looked after Lotus 25 chassis R5, a car owned and raced for many years by Nick Fennell. “I’m a motorcycle man, really,” he says, “but modern bikes have far too many electronic bits. With these, the racing is great fun and we turn the odd screw this way or that – it’s simple mechanical engineering.”

Once Jack Brabham’s first grand prix car was ready, his Lotus 24 was sold on and ended up with South African racer Syd van der Vyver. “It eventually found its way to America,” says Rob Hall, from preparation specialist Hall & Hall. “We brought it back from there in 1998, ran it at the first Goodwood Revival and have looked after it pretty much ever since, through several different owners.”

David Brabham was a guest at Mallory Park to take a look at what Dad was driving in 1962

David Brabham had come along, too, to take a look at another element of his family’s motor racing heritage.

“It’s cool,” he says, “because I’d never seen this car before. I wasn’t born when Dad raced it! So it’s been an interesting history lesson.” Did his father ever mention Lotus customers being annoyed that Colin Chapman sold them the spaceframe 24 while his works team benefited from the groundbreaking monocoque 25?

“He never mentioned such specifics,” Brabham says. “For him this was just a transitional period, between leaving Cooper and getting the first Brabham ready, so he needed something to race. I know he had a certain view about Lotuses at that time – he thought they were very quick, but not necessarily the most reliable cars. But I’m not putting Lotus down one iota – what they were doing at that time was incredible, the benchmark at which Dad was aiming when he turned up as a constructor.”

F1 cars such as Jack Fairman’s Cooper had graced Mallory Libre events; Practice at the International – Graham Hill’s Walker Lotus 18/21, centre; Brabham back in the paddock after the race, having earnt £500; Marriott’s view of the start, as photographed from the press box; Jim Clark took pole but oil pressure problems meant that he only lasted for little over half the distance

Race commentator at Mallory was Keith Douglas, a regular at the circuit, and his 13-year-old son Russell sat alongside, keeping a lap chart. “It wasn’t an official job,” Russell says, “but I suppose it was quite useful. The only part of the track we couldn’t see was the hairpin, so if something happened there I could point out to him who’d gone missing. We could always tell if there was an incident at the hairpin because the crowd would start to swell in that direction, a bit like a Mexican wave.

“I had one of the best seats in the house – and a photograph I took of cars on the grid remains my favourite motor sport shot. I don’t have many clear memories of the racing, but I recall Jim Clark coming up to the commentary box to be interviewed by my father, the two sharing a microphone. To reach us, he’d had to pass through the timekeepers and climb a ladder before then pushing his way up through a trap-door, which seems amusing looking back.” Probably not a routine Lewis Hamilton or Max Verstappen will ever know…

The tight grid line up was captured from the commentary box by

the commentator’s son

For future Motor Sport assistant editor Andrew Marriott, the race had particular significance – his first F1 report, at the age of 18. “I was an engineering apprentice at International Combustion Ltd,” he says, “but had already started contributing Mallory Park club meeting reports to Motoring News and had a motor racing column in The Derbyshire Advertiser, a weekly paper. I’d seen F1 cars at Mallory before in Libre races, but was very excited about the 2000 Guineas, given the quality of the entry. I drove there flat out in my Mini, from Allestree in Derby, and arrived very early, before the queues began. I knew a few of the people involved with cars down the field, but to see the quality of the drivers at the front… It was just brilliant. “I watched from the press box and rushed down at the end to speak to Surtees and Brabham. Was I in awe of any of them? I don’t think so – apart from Jim Clark, whom I considered to be the best – but then I was probably quite bumptious at the time!

“I’ll always be very grateful to Mallory because it was the launch pad for my 60-year career [the subject of a forthcoming book, Is There Much More of This? – a collection of light-hearted essays about his time in the sport], but that race was something else and I have never understood how Clive Wormleighton, the circuit’s owner at that time, managed to pull it off.

“It was the pinnacle of anything that ever happened on four wheels at Mallory.”

The cars are the stars

Above, from left…

1962 Lola Mk4

Despite its lack of an F1 World Championship win in 1962, the Bowmaker Lola scored two podiums

with John Surtees at the wheel

1961 Cooper T56

Of the four cars, this is the odd one out. It wasn’t at Mallory in 1962 but took part in several period F1 races, driven by John Surtees and Roy Salvadori

1962 Lotus 25

Lotus built seven examples of the 25 – its revolutionary 1962 newcomer. This is R5, which went on to take three non-championship F1 wins the following year for Jim Clark

1962 Lotus 24

Jack Brabham had an indifferent ’62, ending the F1 season ninth, but won the non-championship Danish GP in a Lotus 24 – first in all three heats