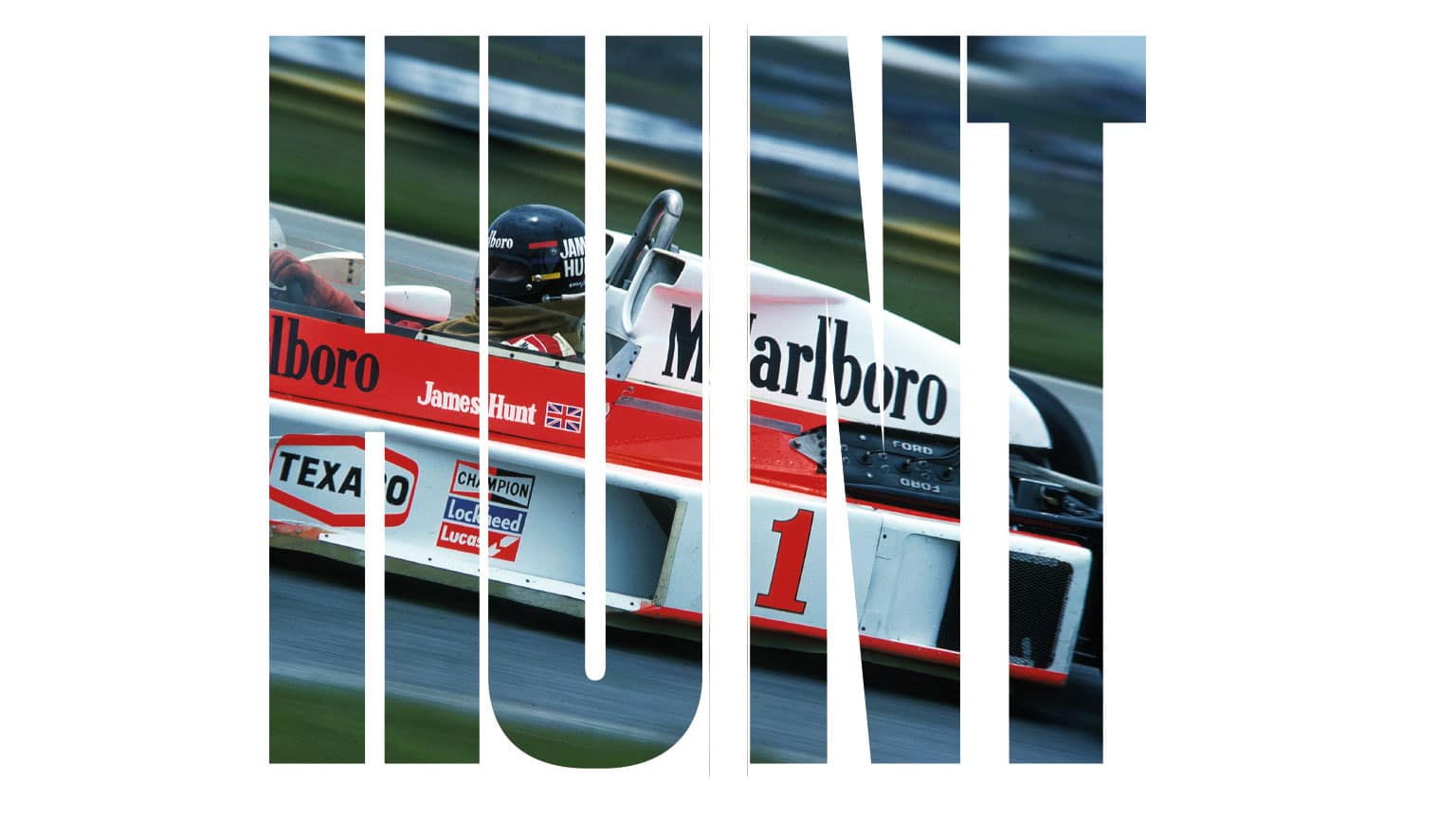

1977: James Hunt's greatest F1 season

He was Formula 1 world champion in 1976, but was James Hunt a more accomplished driver the following year? Damien Smith dives into the ’77 season and gathers evidence to show that our British hero was still firing on all cylinders even if his cars weren’t

Fuji, October 23 1977. A year on from the heart-in-mouth climax that crowned him an against-the-odds Formula 1 world champion, James Hunt has just completed his sole season as world champion – in emphatic fashion. Taking the lead from Mario Andretti’s pole-winning Lotus at the start, he is never headed in his McLaren M26.

If only more days had been like this, he might have matched his old mate Barry Sheene and clinched a consecutive crown. The speed was there, no doubting that, and there had been other high points too, notably in front of his home crowd at Silverstone. That was sweet, especially after the bad taste left by Brands Hatch ’76. But the niggly retirements – suspension failure in Argentina, a broken exhaust and fuel pump glitch at Hockenheim, back-to-back Cosworth woe in Spain and Monaco… He’d never really been in title contention, despite that opening hat-trick of pole positions.

Consistency was James Hunt’s biggest problem in 1977 – the M26 was not the M23

Then there were the shunts: the first-corner launch over John Watson’s Brabham at Long Beach, Andretti’s nerve out of Tarzan at Zandvoort – that outside line, we just don’t do that in F1 – the mess with team-mate Jochen Mass at Mosport and the red-mist punching of (another) marshal. Well, it’s all over for another year. Let’s get out of here.

Celebrating isn’t appropriate, given the two deaths and others injured by Gilles Villeneuve’s cartwheeling Ferrari. But that’s not why James is high-tailing it into a helicopter with Andretti and Watson. “Mario and I wanted to get into Tokyo as soon as possible, so James didn’t even do the podium,” recalls Wattie. “It caused a lot of trouble, a very disrespectful thing to do to the polite Japanese. They were affronted that the winner of their race was in a hurry to piss off to Tokyo to go out to a nightclub.”

A pole at the Argentine Grand Prix but Hunt was out on lap 31

That was James Hunt. That was 1977. If-onlys and misfires around too many turns, in a season during which it could be argued he actually drove better overall than in his title year – when everything was on song. Look at the numbers: three grand prix victories plus the non-points Race of Champions at Brands, versus three for champion Niki Lauda and Jody Scheckter and Andretti’s four; half a dozen pole positions, one less than Mario; the second-most number of laps led, again behind the American. Among eight different race winners in a then-record 17 races, during a competitive and unpredictable season, scoring consistency was the key to a second world title for a physically scarred but mentally impenetrable Lauda. Meanwhile, Cosworth development ambition proved the downfall for Andretti and his amazing new Type 78 as Lotus stopped and started sucking all at once… by triggering the age of ground effect. A zero-slip differential? And the rest, Mario.

Even with the Fuji win Hunt trailed an absent Lauda, who’d stalked out of Ferrari two races early once the title was done, by a gaping 32 points. Between them were his old mate Jody Scheckter, in his surprising new Wolf – even the South African hadn’t expected that – a frustrated Andretti and Carlos Reutemann, who had won early in Brazil before fading from contention. Fifth. From champion to this. How underwhelming. And yet… had James just driven his best F1 season? It certainly proved his last as a top-liner, as the rot began to set in during 1978. Strange to think at Fuji he was only 19 months away from quitting F1 for good.

“Watch out new pads” – a poem from the McLaren mechanics

Watson, quick but winless and desperately unlucky for Brabham in ’77, describes Hunt as “outstanding” in 1976, particularly in the second half of the year. “With respect, he lucked into his title [because of Lauda’s Nürburgring accident], but he made the best of what was offered to him. In Canada and America he was the dominant driver in an excellent car and the team understood how to get the best out of him. As he went into 1977 he had the benefit of being the world champion and felt ‘I can do it again’. But notably a number of things had changed. There was a lot more competition. Niki was back to fitness. Lotus was improving with the 78, in which Gunnar [Nilsson] won a race [at Zolder] and Mario won four. You had Jody in the Wolf and I was in a competitive Brabham. So there were a bunch of others he had to contend with. And on top of that McLaren had the M26, which wasn’t any better than the M23. It wasn’t as easy to find the sweet spot with the new car.

“Therefore, there were a lot of factors that make it difficult to say conclusively he drove a better championship in 1977 than in ’76. But fundamentally he was outstanding in ’77 too.”

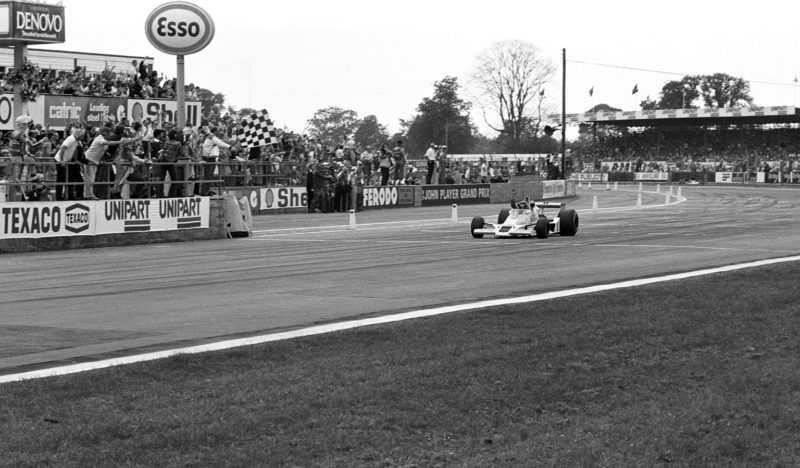

A first win in ’77 for Hunt came in the British Grand Prix

“I would say James drove as well in 1977 as he did in ’76, if not better,” is how McLaren team manager Alastair Caldwell puts it. “For me, the distraction was the M26. [Team chief] Teddy [Mayer], [designer] Gordon [Coppuck] and the factory all wanted the M26 built, I assume because they thought it would be better than the M23. The annoying thing was it wasn’t.” What was it about the M26 that was so troublesome? “Just making it,” he says. “It was a nightmare. The whole place was concentrating for weeks making this thing and not doing anything else. It was a huge distraction. The M23 was heavier, so it would have been better just concentrating on making it lighter, a lightweight M23. And we were totally understaffed, with no test team. It was just the race team.”

Hunt raced the remarkable M23, in its fifth season of active service, in the first four rounds but couldn’t convert his three consecutive poles. He gave the M26 a disastrous debut at Jarama, where an early engine failure put him out, switched back to the M23 for Monaco, then stuck with the M26 from Zolder onwards. By then, his title hopes already looked lost, only for a brief mid-season revival to spur some optimism that a repeat of his Lazarus act from 1976 could be possible. In the mix at Anderstorp, he was third in France behind Andretti and a devastated Watson, who lost victory on the final lap when his Alfa Romeo coughed short of fuel. Then it was time for Silverstone.

Raising a hand at the 1977 British Grand Prix but the McLaren driver still trailed in the drivers’ championship – fifth and 17 points behind leader Niki Lauda

Again, Watson led only to be let down as fuel injection trouble forced him to pit. Behind him and chasing hard after a clutch problem botched his start from pole position, Hunt closed out a home win he’d get to keep (Wattie had to wait another four years for his Silverstone moment). “He was there and always within a couple of seconds of me – a very strong race,” says a generous Wattie.

Watkins Glen was the scene of the other victory of ’77, his second in succession in New York State. Again he lost the lead from pole, then inherited it back from a Brabham, this time Hans Stuck’s, but what marked out this performance was how he nursed overheating wet tyres on a drying track as Andretti closed in. Master James, in the best sense.

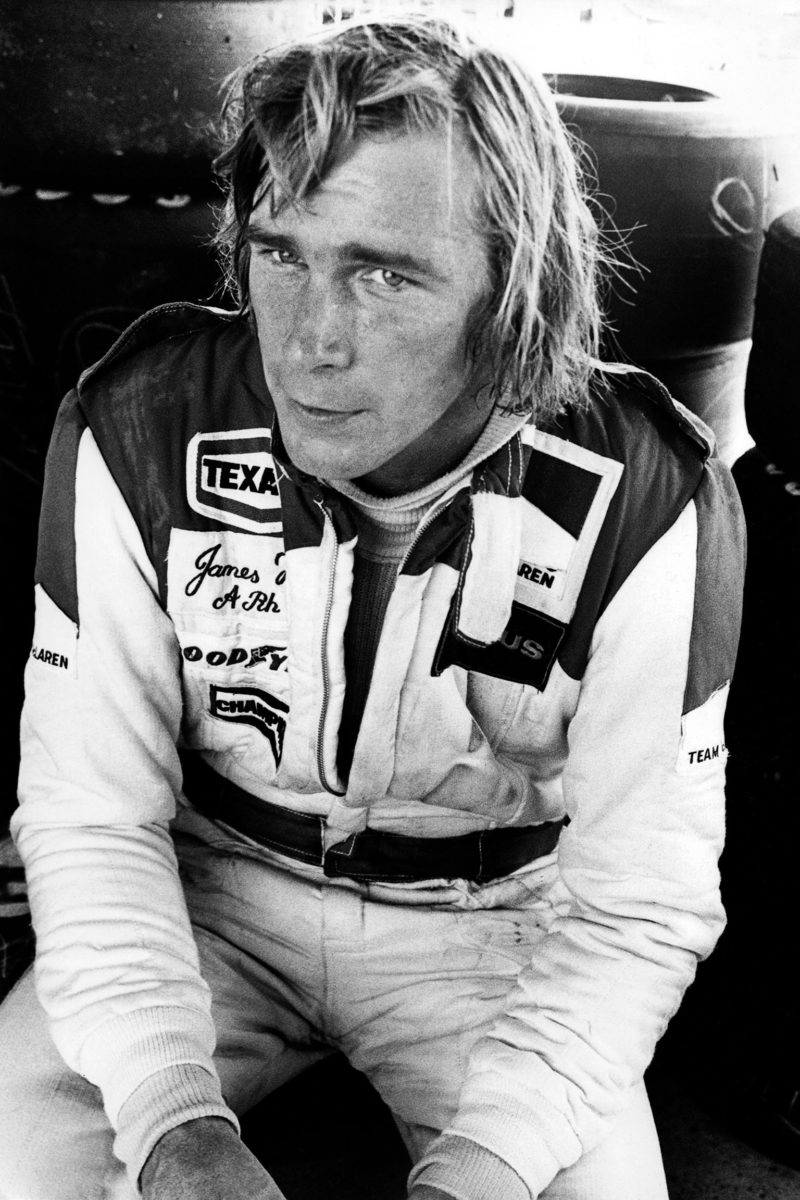

But there were also standout collisions that year too. Zandvoort became a notorious example, as he squeezed up into a challenging Andretti on the exit of Tarzan. Such defence is common now, as we saw at the same corner just a few weeks ago. It still causes a degree of angst, just as it did in 1977. In his book Mario Andretti: World Champion, the 1978 title winner gave his account: “He was inviting me to go on the outside – it was the only race track left to me. He was on the inside every lap, and I didn’t have the straightaway speed to pull alongside him before the turn. I went around the outside of him, and as we left the turn he just moved across like I wasn’t there. I wasn’t going to be driven off the goddam road and rip the skirts off on the kerb.”

As Hunt’s McLaren tripped out, Andretti rejoined fourth, passed Reutemann, closed on Lauda and repeated the move with success, even if it was all in vain as he logged another retirement. “Niki gave me some race track, just like a pro should do,” he said pointedly.

You can almost smell the Brut… Barry Sheene watching his friend at Monaco

On his way back to the paddock Andretti encountered a furious Hunt. “I told him if he didn’t know I was alongside him, he was like a horse with the blinders on,” said Mario. “He told me he had no problem with Watson the year before. Well, of course he didn’t because John drove off the road each lap. And then he said, ‘We don’t pass on the outside in Formula 1’. To me that’s just asinine, especially when he gives you no alternative. I notice no one criticised John for trying it the year before.”

Wattie remembers Zandvoort 1976 well, from his season with Penske. Could Hunt be trusted wheel to wheel? “James was a highly competitive person,” says John. “He was intelligent and had worked out if he had the inside line going into Tarzan and you were on the outside, as Mario and I were, he would sweep up the track and essentially drive you off the track. I backed out of it. Mario believed James understood the etiquette of racing wheel to wheel to give racing room – and James didn’t. I can’t say James was utterly ruthless, but he didn’t give you a lot of extra space and you’re meant to give a car’s width. In those days it was between the drivers, it wasn’t legislated. So that was James being ruthless, being hard or highly competitive.” But Mosport was the nadir. Once again in a duel with Andretti, they came up to lap Mass in the other M26 but in a mix-up the German mistakenly forced Hunt off and into a heavy head-on crash. James’s feet were briefly trapped in the wreck and he was lucky to avoid injury. Then once he was out, blood still pumping, he stood on the track to remonstrate with his team-mate – imagine such a thing today! – and punched a marshal. Not his finest moment, even if he immediately apologised.

A push at Long Beach in ’77 but Hunt, after pitting, would race on, narrowly missing out on sixth by 2sec

“Having done the deed, his education and background trumped the moment and he realised he had done something terrible, so he was very apologetic,” says Wattie.

“He wasn’t aggressive, he was polite,” says Caldwell. “It was the same in the F3 punch-up [with Dave Morgan at Crystal Palace in 1970]. He was hyper. It took me half a day to talk the marshal out of suing us. We gave him all kinds of stuff, gifts, and he decided to go with that.”

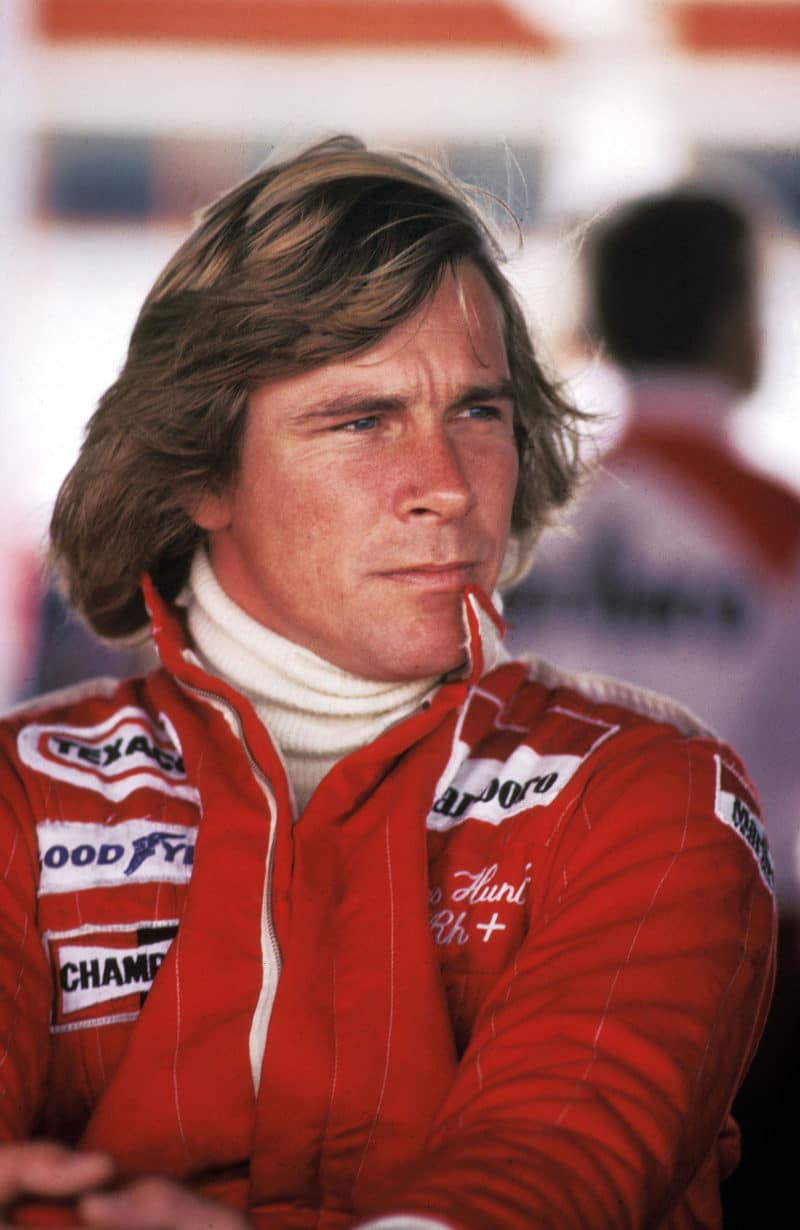

Highly strung at work, Hunt remains infamous half a century later for what we shall euphemistically call his colourful lifestyle away from the track. Modern drivers might marvel at how he played so hard and lived so fast while still performing as a world-class sportsman. But it must have had a negative effect, surely? In 1977 he was at the height of his notoriety. “Having won the championship he became a global celebrity,” says Wattie. “All the women and the media hype… thank God social media wasn’t around.”

John believes there was a “change” in the balance Hunt strived to maintain during ’77. “Some of his behaviour… I remember going to functions, not necessarily black tie but lounge suit, and he’d turn up barefoot, T-shirt and scraggy old jeans. He seemed to take an enormous amount of pleasure in trying to affront or make people uncomfortable. Almost beyond criticism because ‘look who I am’. At that time he was the most famous racing driver. Niki’s fame was more to do with his accident than it was his driving. James’s fame was based on how he won the world championship and then how he conducted himself through 1977, and then into 1978 at the start of a clear drop-off in his performances.

With a local at Buenos Aires for the season opener

“Look at Lewis Hamilton today who has an equally public life. But he balances it. James pushed himself and his body in ways where he wasn’t doing himself favours in long-term life expectancy. Lewis has the capacity to do all these extra things, helped by having private jets, but he has got that discipline to know his day job is in that race car. You can’t live the way James was living in that era and perform to the best of your potential or your ability.”

Scheckter was among Hunt’s closest racing friends – “I don’t really know why” – and saw the best and worst of James up close, even accompanying him to California to party with actor Richard Burton, who was “a bit of a lunatic as well”. But he disagrees that it was all a distraction. “No, that was his style, you know?” says the 1979 world champion. “I remember in Japan, which in those days was very formal, he went to a prize-giving barefoot in a T-shirt and jeans, and as he was world champion that was it, fashion or whatever. But once you’re not world champion it’s just bad manners.”

Caldwell should know best, given how closely he worked with Hunt at McLaren. He takes a typical team manager’s view: “[The notoriety] wasn’t a distraction. No, I don’t think that was a problem. But one of his problems was he wasn’t focused. He was lazy. When we went testing all he wanted to do was go home. He knew exactly what professional racing drivers should do, he knew he should go to the factory and talk to us. But he never came to the factory and if he did come for a seat fitting or something, he wouldn’t go round and meet all the people. He’d just talk to those he knew, then go. Whereas Niki I’m certain after every race went to the Ferrari factory, went round and shook everyone by the hand, told them how well they were doing. James never got that. Compare this to Lewis Hamilton on the slowing down lap: the first thing he says is thanks to everyone in the factory. He talks to them deliberately so when they are watching they think, ‘Wow, he remembers us.’ James never bothered with that.”

No love lost with Mario Andretti at the 1977 Dutch Grand Prix

But Caldwell knew how to get the best out of Hunt across both 1976 and ’77. How did he do it? “Distract him about money! He was always angry about the money because he didn’t make much. He got a better deal in 1977 because in 1976 he got nothing. He had no option then [when Hesketh pulled out]. He had to drive for us so we were able to screw him down, although I wasn’t involved in that. He was always angry that he didn’t get first-class flights. So wind him up and off he’d go! We also borrowed a thing from Hesketh: create an unofficial problem. Have the car on the jacks and say we’ve got a problem. He’d get excited because time was running out and we’d say, ‘Oh it’s fixed, you can go now.’ That would help. A bit of artificial delay.

“He had lots of adrenaline. On the grid you’d think the car was running but it wasn’t. It was just him rattling inside the car. He was just so agitated and that’s why he used to get into trouble when he had a crash or stopped suddenly because the adrenaline was still there, so he’d punch somebody or do something stupid. But that adrenaline was also one of his strong points, of course. And he had fantastic stamina.”

Those who knew Hunt as a racing driver, then in his second professional life as a BBC commentator beside chalk-and-cheese Murray Walker, have said he became much nicer without all that stress, once the dust had settled and the hangers-on had dispersed. But what was he like at the height of his fame?

No smiles at Dijon for Hunt at the midway point in 1977 – a ninth GP without a win

“He could be boorish and a pain in the arse,” says Wattie, who’d known him since the F3 days in 1971. “You’d go into the Marlboro motorhome and it was like the dormitory of an English public school, or a mess hall. There was this thing of ‘who can we take the piss out of today? Who can we prey on?’ They were like a pack of vultures, tearing people to shreds, which is not a very nice thing to witness, never mind being the victim. Poor Jochen Mass had a bit of that, calling him ‘Herman the German’… James never did anything specifically bad where he got chastised for it. But the whole Marlboro side seemed to be like throwing fuel on the fire.”

Yet as ever with Hunt – as with most people in life – that was only one side of him. “He had a lot of ability and some excellent qualities,” says John. “He was generally a good guy, later on a loving father and he loved his dog, Oscar, who was his best companion when he was living outside of England. Then there were the budgerigars he went on to breed. There was this split personality.”

Did Caldwell like him? “Yes,” he answers. “In 1976 James and I spent more or less two weeks together in Japan, because we went testing straight after Watkins Glen. He and I were constant companions and we had a good time. I got on fine with James, but I’d made my decision not to befriend racing drivers after the death of my brother, who was killed in a racing car,” – Bill, killed in a Tasman Series crash, in an accident that also claimed the life of two children – “and then Bruce [McLaren] was my friend. Bruce was killed in front of me. I held Bruce’s crushed body until the ambulance came, wouldn’t let anybody touch him. I just sat and held him in my arms like a baby, and this was deeply scarring for me. After that I stayed in motor racing, but people like James and Nelson Piquet [with whom Caldwell later got to know at Brabham], they both used to invite me on holiday. I said to them, ‘I don’t want to go to your funeral as your friend, I want to go as your team manager.’ I refused to befriend them.”

Hunt’s story is so often dominated by the wildness, the bad behaviour. But through all that it’s also important to remember that when everything clicked he was formidable and could beat anyone. After all, he did it 10 times. As his old friend Scheckter says, with typical wry bluntness, “He was good for a little bit. And then he wasn’t any good.”

The 1978 season started well, with points in Argentina. But the string of retirements and increasing mistakes seemed to revive the old F3 ‘Hunt the Shunt’ reputation he’d long shaken off. It was as if he’d lost interest.

Another retirement – the fifth so far in ’77 – came at the damp Austrian GP; two more would come in the following races

“James’s ethos was ‘I’m not interested in being a racing driver, I just want to win races – I don’t want to be a competitor, I just want to be a winner’,” says Wattie. “In 1979 when he got the Wolf deal there were two things at play. First, the Wolf wasn’t competitive. Second, James had a gambler’s mentality. His rationale was the ‘more events I’m in, the greater the chance there is of me getting killed’, as opposed to looking at it the other way: ‘the more I do it, the more maturity I have, the more knowledge I’ve got, therefore the better I’m equipped.’ He didn’t adopt that policy.” Had he applied himself like Lauda and Andretti, might he have been champion in ’77? Probably not. In those early months of the season, unreliability and the troubled birth of the M26 were the problems, not James. But perhaps with a different outlook his career might have stretched into the 1980s.

“James was a good driver,” says Caldwell. “But he was inattentive, lightweight – he wasn’t a serious racing driver. He thought he was, but he wasn’t. He’d come to the track, get in the car, be quick and go home. That’s all he wanted to do. In retrospect we should have used Mass or a third driver for the testing.”

Fully focused and dedicated to his craft… that version of this champion is an intriguing thought. But in truth, he wouldn’t have been the flawed wonder that still captivates, inspires and makes us smile all these decades later. He wouldn’t have been James Hunt.