Road impressions-2

Daimler Vanden Plas 4.2 Jaguar's extraordinary postwar success has been due, in no small part, to the legendary XK engine revealed in October 1948 and now, therefore, approaching its 35th birthday.…

It is June 11, 1972 and what had always been a dream had come to nothing. What galled was that it was so close to coming true. What would it have been like to race a Ferrari at Le Mans? It seemed that the former boxer Pierre Laffeach and the farmer Gilles Doncieux would now never know.

It wasn’t meant to be like this. Both drivers had been finalists in the previous year’s Volant Shell driving competition. And that entitled them to drive at Le Mans in a car entered by one of the competition’s sponsors, none other than triple Le Mans winner Luigi Chinetti himself. This was the man who had established Ferrari in North America and whose North American Racing Team was the most famous and fabled of factory-supported Ferrari privateer outfits.

And judging that the fearsome competition Daytona was probably a bit too much of a weapon for these young guns to wield at the first exposure to the world’s most gruelling race, he’d prepared a little Dino 246 GT for them to drive instead. No such Dino had ever raced at Le Mans, nor would one ever race there again, not least because its 2.4-litre engine and the fact it was never designed to race ensured it would be uncompetitive in any class for which it was eligible. It was a true one-off.

The NART Dino at La Sarthe was a road car with stickers on its bodywork, but this 246 has been a track regular since the early 1980s

But Laffeach didn’t care, nor Doncieux, or for that matter Yves Forestier, the third man on the driving roster. None had driven a Dino, none had driven at Le Mans. So NART hotshots Sam Posey and Tony Adamowicz took it out first on Thursday practice, one of whom brought it back with a slightly crunched wing but no other damage and pronounced the car ready to race.

It was now Laffeach’s turn to qualify, who did a 4min 53sec lap before beaching it in the sand at Tertre Rouge. Then Doncieux did a 4min 56sec lap. But try as he might Forestier could not get around the circuit in less than 5min and was told he would take no further part in proceedings. Laffeach and Doncieux would have to go it alone, though back then there was nothing novel about just two drivers completing the race. And while they were in 55th position on the grid, which also equated to dead last, on the grid they were.

The great day dawned, and all was fine until their compatriot Alain Cudini, down to drive a Corvette, dropped the bomb. At the other end of the field François Cevert qualified his Matra MS670 in 3min 42sec, and the rules said every competitor must qualify within 130% of the pole position time; the little Dino was about 4sec shy of the mark. It was over. And they were out.

Or were they? There followed a frank exchange of words between the ACO authorities and the now septuagenarian Chinetti. Fists banging the table he told them the entry was guaranteed under the terms of the Volant Shell competition; the ACO said rules are rules. So Chinetti, this legend of Le Mans, who won Ferrari’s first Le Mans in 1949, driving over 22 hours by himself, the man whose NART team won again in 1965 when all the factory Fords and Ferraris faded, issued his ultimatum. If they pulled his Dino from the race, he’d pull his three Daytonas and his Corvette too. “Either we all race, or none of us races”, essentially.

Chinetti was one of few men alive known to give Enzo Ferrari as good as he got and the ACO knew he was not inclined to empty threats. So: “on this occasion and for our French competition winners, perhaps we can make an exception” was the gist of the ACO’s volte-face. Saturday 2pm: with barely two hours’ notice, Laffeach and Doncieux were told they were back in the race.

The steering wheel is on the opposite side to the 1972 Le Mans racer

So now you’re expecting me to tell you how these two young hopefuls, unknown beyond the French domestic racing scene, set about slaying dragons over the next 24 hours, pulling off the most unlikely class victory in the history of the world’s most famous race. But there are dreams which can come true, which is what got the Dino on the grid in the first place, and there are fantasies which cannot. And a Dino winning at Le Mans is the latter.

That race is remembered for a few things, not one of them concerning the little red car circulating at the back. There was Matra’s first win after so many attempts, and Graham Hill’s last victory in a major race. And there was of course the awful accident that claimed the life of Jo Bonnier when his Lola hit the back of a Swiss Daytona at maximum speed and took off into the trees. The Dino? Its crew just tried to keep out of trouble, though Laffeach did once more feel the siren call of the Tertre Rouge sand trap and needed the help of a Red Cross volunteer to release him from its clutches. But the Dino ran faultlessly, flawless throughout, replacing consumables as expected and nothing more. By the end it had covered 265 laps, over 2200 miles and didn’t even come last, leaving a much delayed Porsche 907 to collect that particular dubious honour.

And that was that. There was talk of the drivers doing Daytona the following year, but looking at the entry list, it clearly didn’t happen. Instead the car was sold and then sold again. But it still exists in a private collection and in apparently remarkably original ‘as raced at Le Mans’ condition. This car is not that car. Its steering wheel isn’t even on the same side, but as a racing Dino in NART colours it is without doubt the closest thing that exists to the sight and sound of the original. Owned by Ferrari specialist and restorer Bell Sport & Classic, one of the things I like most about it is that it is not for sale. It was bought because the owner of Bell Sport just loved the idea of it, so it will be retained, and raced, for pleasure alone.

Ironically, the car is a far more grizzled racer than the actual Le Mans machine. Far from being some latterday recreation, this Dino has been racing for the last 40 of its 50 years and comes with a history file many inches thick detailing its every outing.

Visually it is very similar to the Le Mans Dino, though you can spot the differences: the Le Mans car raced with additional driving lights at the front, but without its NART stripe descending below the front air intake. Not all the stickers are the same either, nor in quite the same place. Because it runs on much wider tyres, the standard street wheels of the original were not going to appear here. But the overall look is unmistakeable and unless you have images of each side by side, their differences are immaterial.

This car is also more highly developed. From what I can see, the NART car really was a standard road car save its louvred bonnet, deleted bumpers and so on. The inside was standard 246 as was the instrument pack.

I find it quite wonderful that a street Ferrari with not much more than a set of roundels on its side could nevertheless run flat out for 24 hours without significant problem.

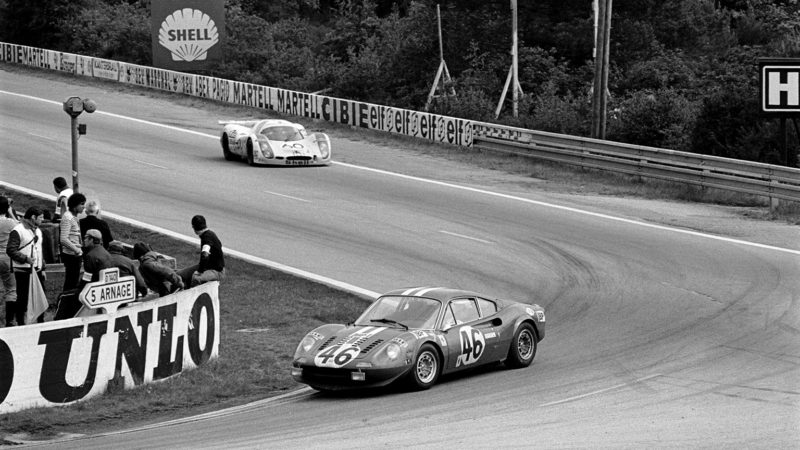

And here’s the original at La Sarthe on its way to finishing in 17th place – second to last

The Dino parked in the Goodwood paddock today is nothing more than you’d expect of a car that’s spent the past four decades as a competition machine. The interior is gutted, the door cards removed, the side glass replaced by Perspex. The body is aluminium like that of the earlier 206 GT road car, not the standard steel 246 GT. Its engine has been massively tuned in the past – up to around 280bhp with a dry sump and fuel injection, but today it’s just nicely warm: its triple downdraft Webers are very slightly bigger than standard, its four camshafts a touch more racy in both lift and duration. The engine has been balanced and ported but that’s about it. So today with a road car wet sump it develops 226bhp at 8000rpm from its 2418cc capacity, compared to 192bhp at 7600rpm for a standard car.

Its brakes are standard with competition pads, the suspension has been stiffened for track use and its split rim wheels carry modern track day Pirelli Trofeo R rubber. Probably the biggest variance from standard is the racing Colotti dog box whose straight cut gears do an impressive job of drowning out the noise of the lightly silenced V6.

I am itching to get aboard. The car may not have much power but I know from pushing it around the paddock that it’s light. A standard Dino weighs 1080kg ‘dry’, so even though this one has a cage, fire system and big wheels and tyres, with its non-existent interior and aluminium body I’m betting plenty it would weigh around a tonne. Happily it’s a ‘noisy’ day at Goodwood and while it hits the 105dB limit, it doesn’t breach it. I can drive as fast as I can make it go.

Might we see another Dino racing again at Le Mans? Maybe this one?

Bell Sport’s Peter Smith, an accomplished racer, has warmed it up, shaken it down and advises that the car is fine but that the gearbox does not understand the gentle touch. And the motor likes to rev. “Use all 8000rpm, all the time, and don’t be shy about the gearchange. The faster and more positive you are with it, the cleaner it will shift.”

The car may never have been intended to race, but its engine is a direct descendant of the unit designed for Ferrari in the mid-1950s by Vittorio Jano in conjunction with Enzo’s ailing son Dino. It was hugely successful in Formula 2, sports car racing, hillclimbing and even Formula 1, taking Mike Hawthorn to the championship in 1958. There wouldn’t be a single component in common between that racing car and this modified road car, but the relationship can still be seen in its curious 65-degree bank angle (chosen by Jano in favour of the more obvious 60 degrees to create more space within the vee for larger carburettors with an even firing interval maintained by offset crankpins), and its addiction to revs.

A surprise for the track-day supercar drivers at Goodwood – a Dino in their rear-view mirror

At first it merely growls at me as we filter onto the track, its sound drowned out almost entirely by the whine from the gearbox. I do a lap just to get my eye in, then at the chicane exit, pin the throttle and go. The Dino is faster by a distance than I thought it might be. We’re at an RMA track day awash with modern supercars, few of whose drivers expected to be having to leap out of the way of the little old Dino. But get that engine in the 5500-8000rpm zone where it wants to be and the thrust is such that I suspect the car is either even lighter or more powerful than hitherto supposed. And if you use all eight grand before calling for another gear, the lever slices around the gate with surgical precision, its speed governed simply by how fast you can move your hand. Apparently you don’t even need the clutch on the upshifts, though I always did. Downshifts are more difficult because the pedals are not quite right for the way I heel and toe, but the lever still bangs home readily enough.

Almost all the Dino’s laptime comes from its chassis. Indeed you drive it the opposite way to how you might approach the same job in, say, a Porsche 911. Ambition on entry is always rewarded. It feels a little bold to be hurtling up to Goodwood’s quickest curves like this, and your confidence is not helped by the fact it essentially doesn’t understeer, but within five laps you’ve learned that its propensity to swivel into high speed turns is not a sign of instability, but natural agility. Just reduce the lock a touch then get back on the power as early as you like, as the engine and transmission compete for your affections by filling in the sound spectrum from a low rumble to an ear-splitting shriek.

The result? Despite the fact the car could benefit from further set-up work – I’d make it a touch stiffer and use a quicker steering rack – every corner at Goodwood save the chicane is taken in fourth or fifth gear. I was in pint-sized Ferrari heaven for every moment.

But despite the fact it felt absurdly at home among the rolling curves of Goodwood, this car needs to be seen somewhere else. It’s been 50 years since a Dino last raced at Le Mans and if the original is not available, perhaps the next best thing might be considered? I can already hear Jano’s V6 howling away into the night. You’d get swamped not just by the Matras, but everything else, and who’d give a damn about that? Just like Laffeach and Doncieux, just to be on that grid would be enough. It would be another dream come true.

With thanks to Peter Smith, all at Bell Sport & Classic and the staff at the Goodwood Motor Circuit.