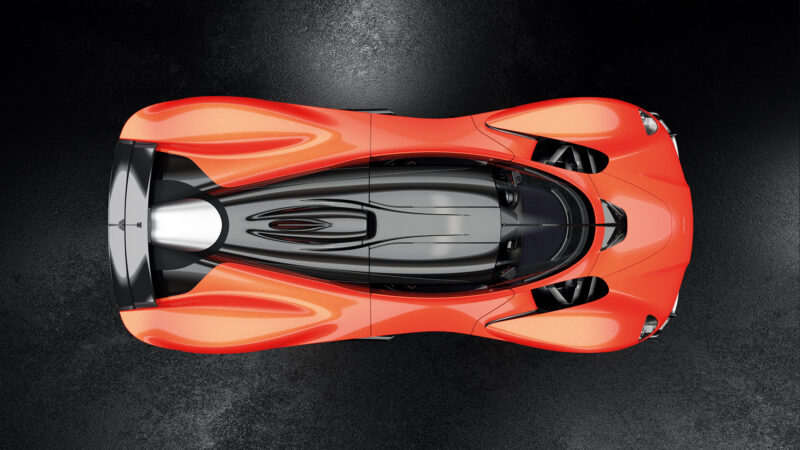

They can do this because both are unimaginably expensive, ultra-low-volume cars that are purely recreational in purpose and which will live as small parts of large collections and only be brought out, if at all, when conditions and the environment are exactly right for them.

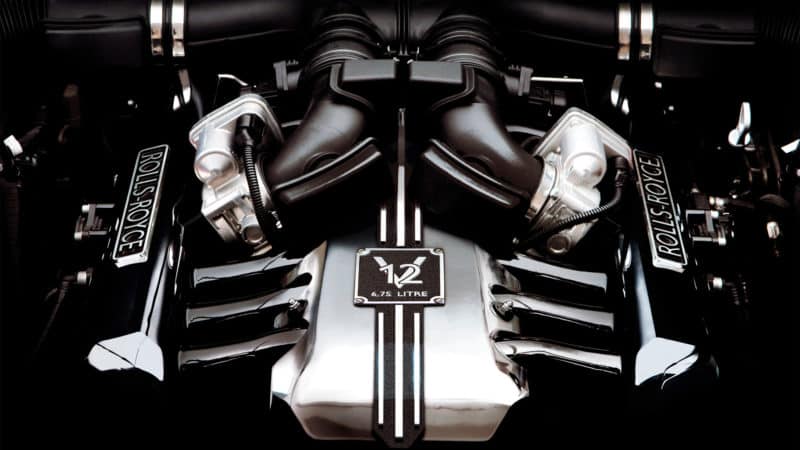

But why did both companies choose a V12 configuration? For Aston Martin it wasn’t actually an immediate choice. They looked briefly at a V8 and rather longer at a twin-turbo V6 but ultimately reached the same conclusion at which Gordon Murray arrived, albeit for slightly different reasons. Aston chose a V12 partly because, well, it’s a V12, but also because its relatively narrow (65-degree) vee angle and absence of turbos, intercoolers and associated plumbing would provide as little impedance of the air flow under the car as possible, allowing downforce to be maximised. Gordon Murray chose 12 cylinders largely because he felt that it was the ultimate configuration for his ultimate road car.

Hybrid Aston Martin Valkyrie can call on an electric boost

Interesting that. Twelve cylinders, not 16. True, V16 road cars have not been around for quite as long as V12 road cars but they’ve still been built on and off for over 90 years. There’s no specific engineering reason for it: a V16 is perfectly balanced so I think what we’re seeing is the Goldilocks effect coming into play. Engines below a certain capacity don’t gain enough in terms of additional power over a V12 than they lose in terms of mechanical complexity, which is why the only 16-cylinder engine in production today is Bugatti’s 8-litre monster used in the Chiron. That said, if you built, say, a 6-litre supercar engine with fewer than 12 cylinders, you might not be too bothered about the potential lost power, but some people will just feel a little short-changed.