The V12 engine's rise to power

With a lineage that takes in boat racing, aero-engines, the Land Speed Record and F1, the V12 engine has brought joy and tragedy along its journey. Paul Fearnley delves into the engine’s history to find out why its notes stir the senses like no other

Triplex, owned by wealthy American JH white, left, had taken the Land Speed Record in 1928 with Ray Keech driving. When Keech refused another LSR attempt for White, garage owner Lee Bible, right, was drafted in — with disastrous results

ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images

Ultimately it was the sound. Higher rpm delivered smoothly thanks to smaller, lighter reciprocating parts and an even firing order, plus the cachet of costly complexity, added to its appeal. But only when trusted engineering lieutenant Luigi Bazzi roared off did Enzo Ferrari break into a smile.

Just prior to holing his driving career by slinking from the 1924 French Grand Prix, Enzo was beguiled by Delage’s groundbreaking 2-litre; and though no match for the supercharged straight-eight Alfa Romeo P2 that he was meant to drive, that ‘song’ never left him.

Now, 23 years later, he had a V12 of his own. That it sat in a rudimentary chassis sans bodywork was of no importance. Only that beating heart mattered. With a chirrup on the cold cobbles of Maranello’s courtyard, he accelerated along the three-mile straight to Formigine, as his small team held its breath.

The harshest winter in living memory and an ambitious project running 12 months late had strained relationships. Engineers Giuseppe Busso and Aurelio Lampredi had quarrelled about how best to interpret and implement the absent Giaocchino Colombo’s schemes and sketches for this oversquare –a bore and stroke of 55×52.5mm – 1.5-litre. The atmosphere was tense on March 12, 1947.

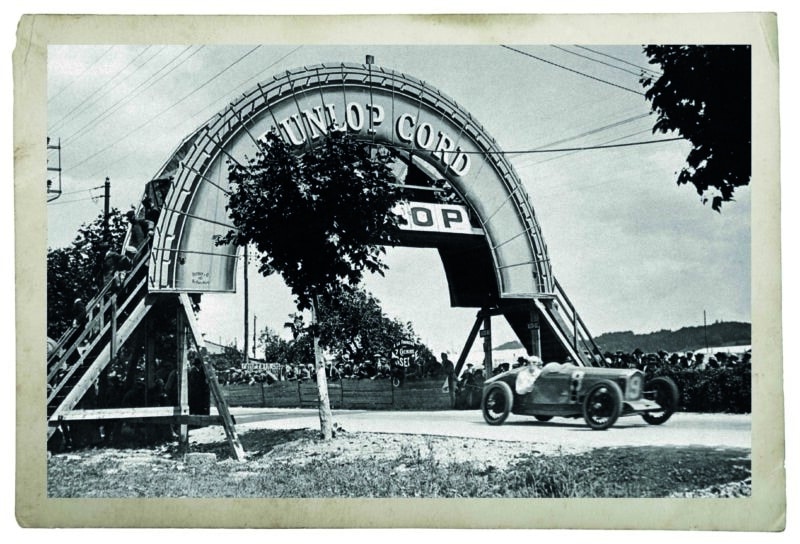

Robert Benoist in a Delage 2-litre V12 races through Dunlop Bridge at Lyon in the 1924 French GP. No9 came in third, almost 11-1⁄2mins behind winner Giuseppe Campari in an Alfa

GP Library via Getty Images

The car coasted in upon its return. It was nothing without the noise. Bazzi spotted the oil streak that had caused Ferrari to switch off. Offending cam-cover bolt tightened, he took his turn at the 125’s wheel. Now it dawned on Ferrari, face still stinging but ears no longer buffeted: it sounded as good if not better from outside the cockpit.

He wrote in his 1963 memoirs My Terrible Joys: “It was forecast that I was bringing about my downfall, the experiment being just too daring and presumptuous.” In fact, daring assured this conservative man’s future. For Colombo’s neat ‘short block’ – separately machined, press-fit cast-iron wet liners packed tightly but with sufficient meat for future expansion, and shallow hairpin valve springs – not only brought immediate racing success but also would underpin the world’s most glamorous car brand for the next four decades.

A V12, however, was nothing new. The first –a 90-degree for marine usage – emerged from Putney Motor Works in 1904. Early iterations, however, were restricted by prevailing bearings and ignition systems to large, (relatively) low-revving applications in aeroplanes, motorboats and luxury cars.

Henry Segrave with the V12 Sunbeam which reached 152.33mph at Ainsdale Beach, Southport in 1926

Sunbeam driver Kaye Don, left, and the French-born engineer Louis Coatalen, far right, at Daytona Beach in 1930

National Motor Museum via Getty Images

In the early 1920s Packard in the US started development of new V12 aero-engines, which were inverted so the propeller had maximum ground clearance

Alamy

It was Sunbeam of Wolverhampton’s Brittany-born chief engineer Louis Coatalen who fitted a 200bhp side-valve 9048cc to a single-seat racer nicknamed Toodles V after his wife. Banks of two iron blocks-of-three were at the preferable 60 degrees, the left slightly forward to allow for side-by-side big ends on the same crank pin. Along with the camshaft within the vee, they were atop an aluminium crankcase with novel dry sump. The car shone at Brooklands: most miles in an hour being among eight world records in 1913. In truth, it was a test bed for an aero-engine – development was easier and safer on the ground – made urgent by impending global hostilities. Actual combat would further force technology and production.

America’s Liberty L-12, designed in five days by Packard’s Col Jesse Vincent and Elbert Hall of Hall-Scott, generated a robust albeit lumpy 400bhp from 27 litres, and was built in huge numbers: almost 14,000 by the Armistice. Its power and availability, plus that of Sunbeam’s Manitou and Matabele designs, fuelled the Land Speed Record in the ’20s.

“Segrave was pushed beyond 200mph on Daytona Beach”

Coatalen’s latest ‘aeroplane on wheels’ achieved 133.75mph when driven by Kenelm Lee Guinness at Brooklands in May 1922. However, though based on Manitou, with elements of its smaller Arab V8 cousin – aluminium blocks with integral heads containing three valves (one inlet, two exhausts) per cylinder, operated by a SOHC per bank – Sunbeam stressed that this was not an aero-engine. A twin-spark 18.3-litre featuring articulated conrods to shorten crankshaft length, the latter held by seven white-metal bearings, it produced 357hp at 2500rpm. Purchased, modified and rebranded Blue Bird by Malcolm Campbell, it broke 150mph on Pendine Sands in July 1925.

Coatalen had designer Capt JS Irving place a four-cam four-valve twin-spark 22.4-litre Matabele into the nose and tail of Sunbeam’s challenger of 1927. Though their combined output was less than the boastful 1000hp painted on the red car’s flanks, it pushed Henry Segrave beyond 200mph on Florida’s Daytona Beach in March.

Sunbeam’s 1000hp Mystery was powered by a brace of 22.4-litre Matabele aero-engines and in 1927 at Daytona Beach became the first car to smash 200mph

National Motor Museum/Getty Images

The White Triplex that ran 207.55mph in April 1928 featured three war-surplus Libertys: one out front and a side-by-side pair out back: 1500bhp from 81 litres! Driver Ray Keech wisely refused a second attempt and the aptly named Lee Bible, a garage owner with no prior experience, stepped up. He and a Pathé cameraman, Charles Traub, were killed in the ensuing accident.

But the LSR wasn’t all thunder and blood. Delage’s DH of 1923, though hardly small at 10.5 litres, was sufficiently manageable for 4ft 10in Kay Petre to lap Brooklands at 134.75mph in August 1935. And Sunbeam’s 18cwt 300bhp 4-litre, which Segrave steered to 152.33mph on Southport’s beach in March 1926, also led that year’s Libre road races at San Sebastián and Monza before retiring.

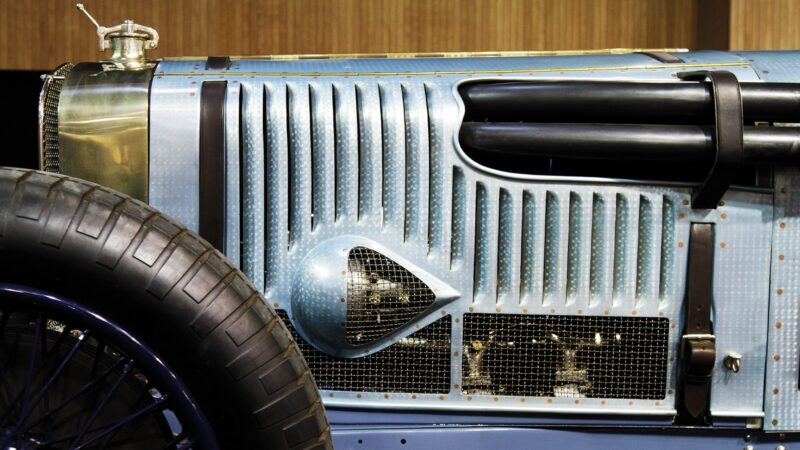

The V12 of the Delage 2LCV was an inspiration for Enzo Ferrari.

Richard Bord/Getty Images

Delage’s 2LCV, however was a genuine no-compromise GP car. Gear-driven twin- overhead camshafts per staggered iron bank operated two valves – at an included angle of 100 degrees – per cylinder in fixed heads with hemispherical combustion chambers. A one-piece crankshaft was held by split-cage roller bearings, seven of them, as were the big ends. And those 23 timing gears ran in ball races. Lilliputian pistons with a stroke of 80mm equated to 1992cc.

The car was rushed through for the 1923 French GP at Tours and led briefly from a pole decided by ballot before retiring early. Louis Delage promptly sacked designer Charles Planchon – his cousin! – and placed underling Albert Lory in charge. Supercharging was considered for 1924, but an updated 120bhp version ran unblown and unspectacularly at Lyon to finish 2-3-6 behind Italian Giuseppe Campari’s Alfa P2.

The 1923 Delage DH V12 photographed at Goodwood Revival

Alamy

When Roots-type superchargers were adopted, one per bank, for 1925, the effect was profound due to a large piston area: a 70bhp increase at 7000rpm. After a disastrous European GP at Spa – Lory had neglected to incorporate pressure-relief valves in the inlet manifolds – Delages finished 1-2 at Montlhéry and 1-2-3 at San Sebastián. Alfa’s was still the quicker car, however: Antonio Ascari’s P2 was leading in France when he crashed fatally and the team withdrew; and the Milanese skipped the Spanish event.

V12’s GP zenith remained some way off. It was, however, still the thing for the LSR.

The supercharged 36.7-litre Rolls-Royce R won the biennial Schneider Trophy for seaplanes twice consecutively from 1929 before topping 400mph in Supermarine’s S.6B. Its 2800hp then pushed Campbell’s latest Blue Bird beyond 300mph on Bonneville’s salt flats – more space for more power – in September 1935. George Eyston’s Thunderbolt used two to reach 357.5mph three years later.

the Schneider-winning Supermarine S.6 of 1929 was powered by Rolls-Royce’s V12 R engine

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Pure speed in Europe had a different look, smaller, more efficient cars gunning along Hitler’s autobahns at 250mph. Mercedes- Benz had hoped to use its 600bhp 5.6-litre DAB in GPs in 1936, but it came in much too heavy. The compensatory lopping of 25cm from its intended chassis resulted in a cramped mongrel reliant in any case on an overstretched straight-eight. DAB would be the preserve of record-breaking thereafter, although Manfred von Brauchitsch drove one, now delivering 736bhp, to a heat victory at the 1937 Avusrennen. His streamliner retired on the Final’s opening lap. These were rare problems for a team otherwise incredibly advanced and meticulously organised.

Spurred by an Auto Union lacking the resources to beat Mercedes-Benz at its own game and therefore adopting a radical and cheaper but prescient approach, these Silver Arrows raised technology and build quality to levels unmatched in GP racing until the late 1980s. And both outfits plumped for a 3-litre V12 for their W154 and D-type models for the formula introduced in 1938: a sliding scale of minimum weights (from 400-850kg) for engine sizes from 666-3000cc supercharged/1000-4500cc normally aspirated.

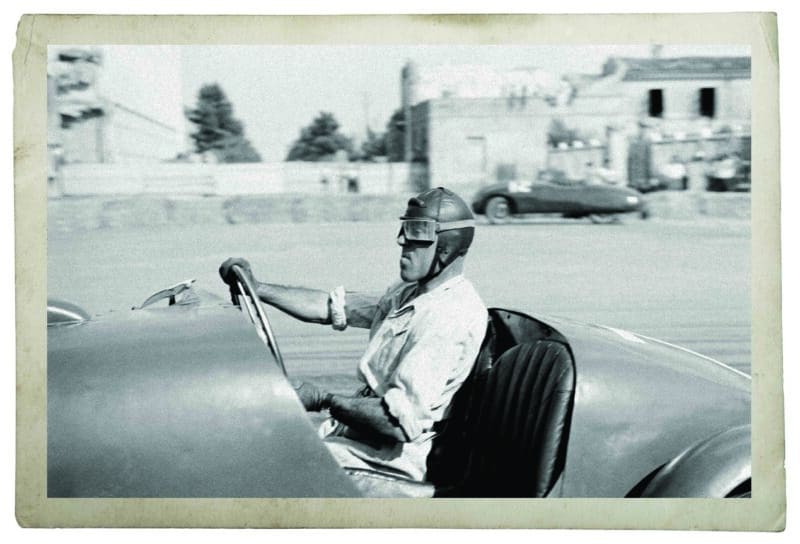

The portly Mercedes-Benz race manager Alfred Neubauer with the 3-litre V12 W154 at the 1938 French GP

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Each were high-compression, high-revving – undersquare yet upwards of 7500rpm – high-boost units benefiting from Roots-type superchargers, a pair for the Mercedes, a singleton for the Auto Union. The former had forged steel cylinders within welded water jackets, whereas the latter’s blocks (with steel wet liners) and detachable heads were aluminium. Mercedes opted for four valves per cylinder operated by twin overhead camshafts per bank, whereas AU went two and three, a central camshaft acting on the inlets while the outers, driven by short cross- shafts and bevel gears, managed the exhausts. Mercedes’ one-piece crankshaft ran in seven roller bearings, whereas AU’s fabricated Hirth- type ran in plain, although the big and little ends of its one-piece conrods featured rollers.

Both had a prodigious thirst, especially when two-stage supercharging –a larger primary feeding an in-series secondary – boosted output toward 480bhp by mid-1939. The Mercedes carried almost 90 gallons of carefully blended fuels, which it guzzled at 2-3mpg: the price of victory. Though its V12 was shorter than its previous V16, Auto Union fitted a smaller central fuel tank so that the driver could be moved further back between saddle tanks: the next GP generation was taking shape. Gradually.

Delahaye’s 145 was a truck in comparison, its pushrod OHV 4.5-litre by Jean François featuring blocks from magnesium alloy and two spark plugs per cylinder but generating just 250bhp, albeit frugally and with gobs of torque. A two-seater built for Lucy O’Reilly Schell’s Ecurie Bleue to win the Million Franc race –a government-backed time trial at Montlhéry in August 1937 intended to give (eventually false) hope to French manufacturers. Entered for the Pau GP of April 1938, René Dreyfus beat the unsorted Mercedes-Benz to pole and won, running non-stop in a car with a power perfectly suited to a tight street circuit slicked by oil. The monoplace 155, however, was a bust.

The Swiss Grand Prix in August 1938, with the 3-litre V12s of Auto Union and Alfa Romeo.

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Alfa Romeo, via Scuderia Ferrari, tried harder to keep up with the Germans and achieved a little more success. Initially. If a track was slow. And usually if Tazio Nuvolari was driving. Designer Vittorio Jano’s challenger of 1936 had received a supercharged 370bhp 4.1-litre V12. But it wasn’t enough. His lower-slung effort of 1937 was stretched to 4.5, had two smaller superchargers instead of one, and roller bearings instead of plain. It cost him his job.

Alfa stepped in for 1938 and created an eponymous Corse (employee Enzo hated it). Jano’s replacement, Spaniard Wifredo Ricart (Enzo hated him, too!), with Colombo’s assistance, threw everything at the new formula – straight-eight, downsized V12, twincrank V16 – to marginal effect. Their next project, however, was a what-might-havebeen: a red ‘Auto Union’.

Auto Union was reportedly developing a 327bhp V12 for the 1.5-litre GP formula purported for 1941. Colombo’s response was a fractionally undersquare flat-12 with two camshafts per bank, two valves per cylinder and two-stage supercharging at 32psi. It weighed less than the 225bhp blown straighteight of his 158 Alfetta of 1938 and developed 335bhp at 8600rpm. Ricart placed it behind the driver. Alfa threatened to wheel out Tipo 512 after the war, but its Alfetta, improved by Colombo and eventually boasting 400bhp, continued winning so there was no need.

Underachieving over-ambition is a coda of this part of V12’s story.

At Porsche, Karl Rabe’s F1 design for Cisitalia’s Piero Dusio was a 4WD with an oversquare 1.5-litre flat-12 with three superchargers (two in the flesh) sited behind a driver operating a sequential motorcyclestyle five-speed gearbox with synchromesh to keep it singing: beyond 10,000rpm was projected. Dusio ordered six. When inevitably bankruptcy beckoned, he struck a deal in 1949 with dictator Juan Perón to found Autoar [sic] in Argentina. The only completed F1 car was shipped over but never raced.

Alfa’s mooted Tipo 160 for the new F1 of 1954 was said to be a 2.5-litre flat-12, probably a 4WD, with its driver hung beyond the rear axle. A modified Alfetta assessed that odd seating position – the slipstream whipped off the goggles of an otherwise satisfied Consalvo Sanesi! – but the project went no further.

These are just two of the many: a competition V12 of this period was no sinecure.

Maranello, from left, Giovanni Bracco, Enzo Ferrari, Gioacchino Colombo and Luigi Vllloresi

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

The war in the Pacific was raging still when Colombo drove from Milan to Maranello using black-market fuel, and a barge to cross the Po, the bridge at Piacenza having been destroyed. Maranello had been bombed, too – twice – but this smaller, nimbler company, yet lacking the foundry that would make it a reactive powerhouse, was recovering more quickly than an Alfa Romeo reduced to making kitchen utensils. Colombo, in turn, was moonlighting while communists assessed his fascist ‘sympathies’ –a twitchy business given that his former boss Ugo Gobbato had been assassinated – and began work in a bedroom/ studio on a borrowed drawing board. Before the year was out, Alfa would recall him to revive and refresh 158. Ferrari’s project stalled.

Colombo recommended Busso, who was joined in Maranello’s sparsely populated, inexperienced drawing office by Lampredi, four years the younger but with a more forthright manner. The engine intended as a racing unit first and a series-production item second ‘burst’ into life on September 26, 1946: 60bhp at 5600rpm! Thinwall shell bearings couldn’t come soon enough.

Power had almost doubled by the time Franco Cortese gave it its competition debut at Piacenza on May 11, 1947; he retired lately from the lead because of a faulty fuel pump. A fortnight later he won at Rome – and then was victorious at Vercelli, Vigevano and Varese. Minor stuff, but wins nevertheless. Nuvolari’s successes at Forli and Parma gained much more favourable press for Ferrari. And Raymond Sommer’s in Turin in October was its first international win.

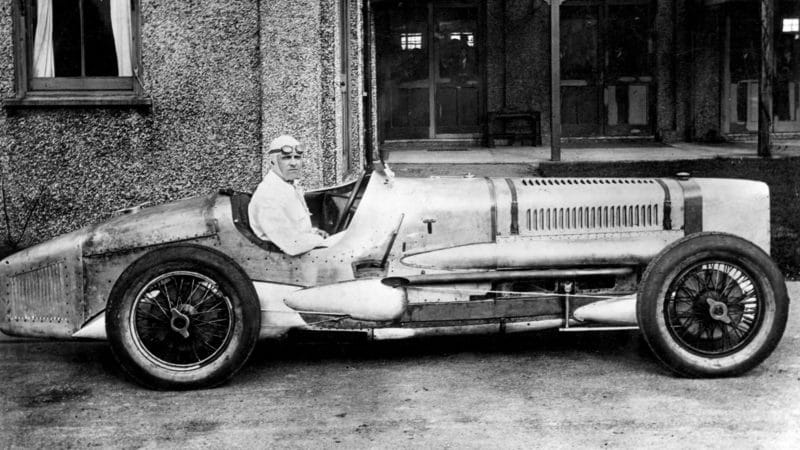

Tazio Nuvolari in the Gioacchino Colombo- designed Ferrari 125S, with its 60-degree 1.5 V12

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Colombo, embroiled in more controversy at Alfa, was contributing again. His criticisms caused Busso to leave (Lampredi had already joined Isotta-Fraschini). Colombo played hardball with Enzo: he would work part-time and commute from Milan. He was of the ‘Jano school’: a hands-on innovator with little time for theory. In contrast, Lampredi, returned on a full-time basis and more methodical and considered, was reluctant to veer from a finalised drawn design. Divergent paths.

Giuseppe Farina scored Ferrari’s maiden F1 victory at Garda on October 24, 1948, but its stubby single-seater was no match for the Alfetta at the more prestigious races. The latter would take a sabbatical in 1949, as would the works Maseratis – BRM, meanwhile, was busy proving that 16 was four pots too many – and so Ferrari would make hay, winning the Swiss and Italian GPs, plus the Mille Miglia and 24 Hours of Le Mans and Spa.

“That V12 note, in the darkness if necessary, was a siren’s song”

Its sports cars and F2s continued to rack up victories in 1950, but its F1 car, even in 315bhp twin-cam two-stage-supercharged form (by Lampredi), was easy meat for the Alfetta upon its return for the inaugural World Championship. Lampredi’s dissenting voice was heeded. Having twice been beaten in 1949 by a Talbot-Lago making fewer pitstops, and correctly positing that Alfa’s straight-eight was at the end of its development tether, he proposed a normally aspirated 4.5-litre V12 (Colombo had rejoined Alfa Romeo).

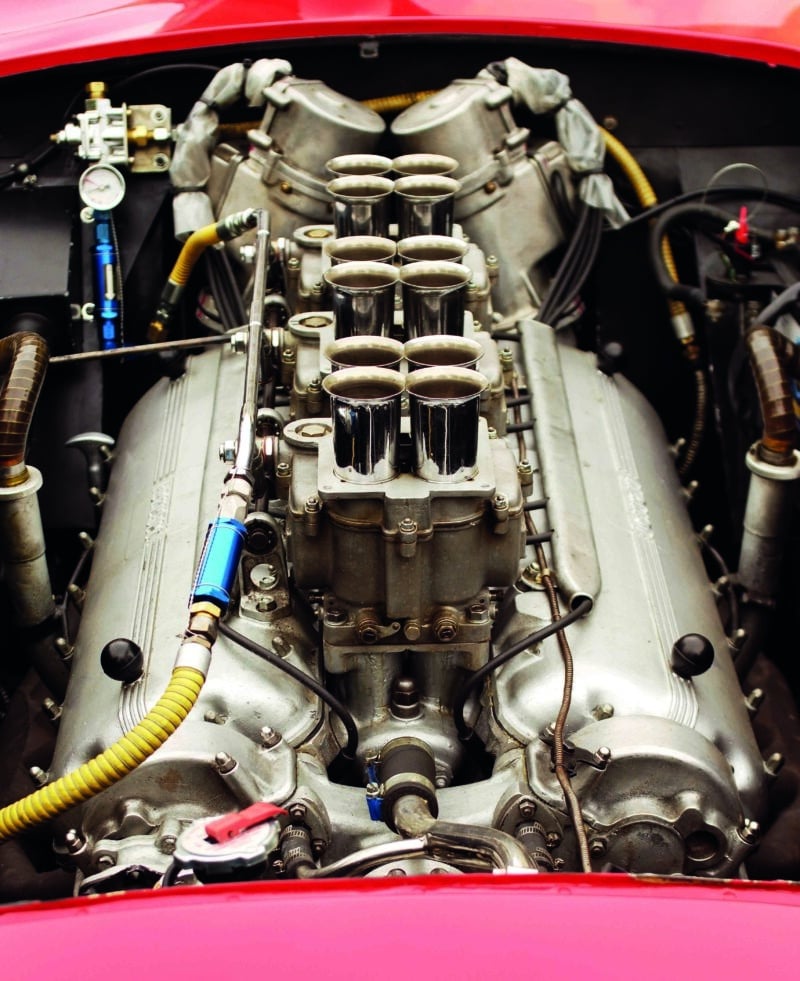

Ferrari’s 4.5-litre V12 of the 1953 375 MM Scaglietti-bodied Spyder

Alamy

Increasing from 3.3 via 4.1 to 4.5 in 1950, while maintaining oversquare dimensions, chain-driven SOHC and two valves per cylinder, its head and blocks were cast as one, its cylinders threaded. This more complicated method was labour-intensive and indicative of Enzo’s desire and his company’s confidence. He loved Alfa but railed at how it had treated him. He got his revenge with Ferrari’s victory at Silverstone 1951: “I have killed my mother.”

Lampredi’s 375, now a twin-spark, had the upper hand and Alberto Ascari won in Germany and Italy; likely he would have become champion but for a poor tyre choice at the Barcelona finale. He would, however, dominate the next two championships, reduced to F2, using a 2-litre ‘four’; paying for the design and build of full-shot GP motor of any configuration appeared prohibitive. Those successive wins in 1951 were the only three by a V12 among the 29 World Championship GP victories achieved by Ferrari that decade. Engines of eight cylinders or fewer, the vast majority in-line, won the other 81 rounds.

Swiss driver Gérard Spinedi flings his Ferrari 250 GT SWB into the Gasworks Hairpin at Monaco during the 1963 Tour de France.

GP Library via Getty Images

Sports car racing — packaging less restrictive and important, reduced vibration a boon for extended reliability – was different. Ferrari won 19 of 42 rounds of a World Championship created in 1953. All bar two were scored by a V12. Lampredi’s ‘long block’ was a potent force in the middle of the decade, and Jano’s interim – Lampredi departed after a disappointing 1955 – continued the theme with a mix of Lampredi architecture and Colombo internal dimensions, along with the adoption of twin-overhead cams per bank.

A reduction to 3 litres from 1958, however, had sparked the resurgence of Colombo’s original. Having already begun its association with the 250 GT dynasty, a modified 1953-style block was used by new tech chief Carlo Chiti to power a second-generation Testa Rossa to Ferrari’s fifth world title in six years.

These endurance races were what piqued vital American interest in burgeoning Ferrari. That tingling V12 note, howling in the darkness if necessary, was a siren’s song. It took time for Enzo to appreciate the former fact. He understood the latter sensation the moment he heard and felt it: a sound investment.