Skill was paramount, success perhaps less so. Charisma trumped championships and personalities beat points. But crucially we debated names which have resonated with the racing public, the media and hopefully you, the reader, down the years. We discovered that the names we came up with had certain things in common. They’re the hard-chargers, the never-give-uppers, the ones who brought a bit of flair and elan to their craft even, perhaps especially, when the odds were against them.

They are unique characters that only motor racing could forge and that true fans deep down admire because they possess some ineffable quality that marks them out. To deploy a neologism: if you know, you know. To celebrate these characters and allow you to have your say too, we have created a new Cult Hero category for this year’s Hall of Fame allowing readers to vote for their favourite. Visit the website to join the debate and watch out for updates over the coming weeks. For now, dive in to our choice of some of the most incredible and talented characters any sport has ever produced.

30: Archie Scott Brown

Never let his handicap hold him back

He would likely have been appalled at any suggestion he was a pioneering ‘champion of disability’, because popular, ebullient Archie Scott Brown spent most of the 1950s ignoring his own physical disadvantages. The Scot was born with a severely deformed right arm, legs and feet and had to fight his entire life. Scott Brown, always flamboyant behind the wheel, proved fast for Connaught in F1, but it is with Brian Lister’s Jaguar-powered sports racers that he will forever be most associated. Twice a winner of the British Empire Trophy at Oulton Park, he died after crashing at Spa’s La Source, naturally while battling for the lead.

29: Guy Moll

A ‘freak’ talent, cut short

“He was the only driver, together with Moss, able to be placed alongside Nuvolari.” Enzo Ferrari’s verdict still resonates. Urbane René Dreyfus described Guy Moll as “a freak talent; another Rosemeyer, a Villeneuve.” Algerian-born Moll burst on to the scene in 1931 and by ’34 had earned an invitation to join Ferrari’s team of Alfa Romeo P3s. On his debut at Monaco, he inherited victory when team leader Louis Chiron crashed, but his finest day was at AVUS where, in a P3, he shocked Auto Union on its home turf by defeating Hans Stuck. That summer, Moll’s story was cut brutally short by a fatal crash at Pescara. A GP winner at 23, lost by 24.

28: Parnelli Jones

Champion turned team boss

“Parnelli was the quickest guy in a race car I ever saw,” said Rodger Ward of an Indycar folk hero who, like AJ Foyt, successively straddled the roadster era and the 1960s rear-engine revolution. His single Indy 500 win, in 1963, was coated in controversy after his Watson-Offy trailed oil in the closing stages. Had officials black- flagged him, Jim Clark’s Lotus would have won – so they didn’t. In ’67, a $6 bearing cost him a second win after dominating in the four-wheel-drive Granatelli Pratt & Whitney turbine. Also a winner in NASCAR and a Trans-Am champion, Parnelli enjoyed success as a team owner in F5000, but failed to crack F1 with Mario Andretti in the ’70s. A rare shadow on a wonderfully diverse life.

27: Henri Toivonen

The youngest champion who never was

F1 had Gilles Villeneuve, rallying… you know the rest. The stages breed natural-born, free-wheeling heroes – they always have, always will. But above Walter Röhrl, Markku Alén and the rest sits Henri Toivonen, uncrowned king of a sport he grabbed by the scruff in the early 1980s. From his first successes in a Talbot Sunbeam Lotus, including an RAC Rally win in 1980 aged 24 that made him the youngest WRC winner at the time, Toivonen pressed on as only he could with Lancia through the Group B era. He was quick on the circuits too, but the world lost the chance to see what more he could achieve when his Delta S4 plunged off a Corsican road, the subsequent explosion killing both Toivonen and co-driver Sergio Cresta. Something more than two talented young men died that day. Yes, it was the end of Group B, but it also ripped the heart from the sport. Like the aftermath of Ayrton Senna’s death, in rallying nothing was quite the same again after.

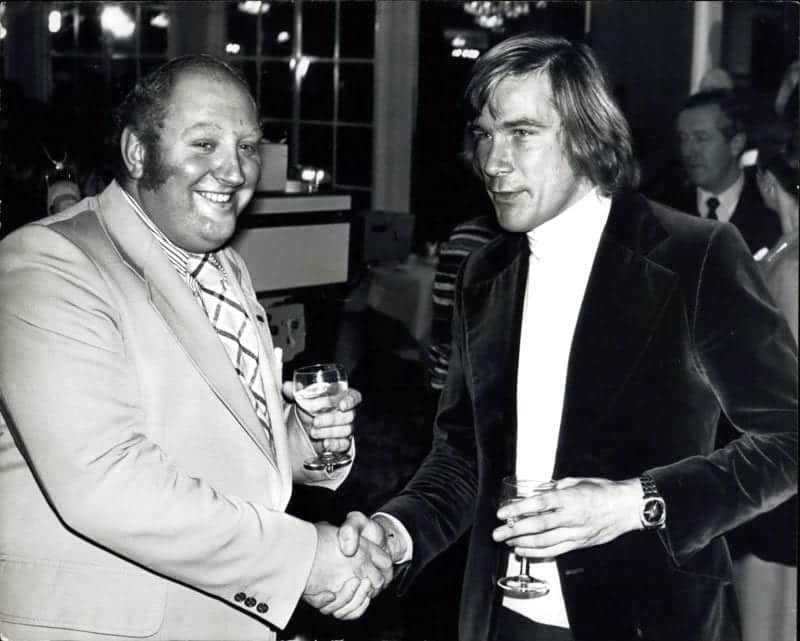

26: Gerry Marshall

As familiar with big-engined beasts as he was with a bar, he became a national hero

Gerald Dallas Royston Marshall. Where do we possibly start? ‘Big Gerry’ (some called him other names) started out in Minis of all things, deep in the heart of the mid-1960s. But it was in the next decade driving for Dealer Team Vauxhall where he really showed why no one could touch him for talent – in his opinion. Bill Blydenstein’s heavyweight Big Bertha (“handles like a double-decker bus around Woodcote”) and more successful Baby Bertha Super Saloons added to his notoriety, in the wake of celebrated antics in a Viva GT and a potent Firenza, which Marshall revelled in nicknaming ‘Old Nail’ – Vauxhall’s most prolific race winner. But he’d race anything anywhere if there was a win to be had. More than 600 were clocked up between the odd pint and running race – he was seriously fast, goes the legend – in everything from one-make Escort Mexicos, in which he beat a young Jody Scheckter to the inaugural title in 1971, to in later years Marsh Plant Aston Martins and TVR Tuscans.

An annual star of the Goodwood Revival, he naturally dived headfirst into the historic racing boom, but in 2005 his heart gave up the fight while he was testing a Camaro at his beloved Silverstone. He was 63. At his funeral, Wild Willy Barrett, collaborator with John Otway, played him out after his final drive in the Alvis Grey Lady, which he’d thrown around Goodwood with signature gusto. The perfect send-off for a man who was larger than life in every sense.

Top: Marshall hustling Baby Bertha at Silverstone in 1975, and here, enjoying a drink with James Hunt

Getty

25: Georges Boillot

A pioneer who was hard to like

Vain, brash, arrogant. France’s great pre-World War I hero might have been hard to like, but who cared when he was hustling Peugeots to their limits on the rutted, bumpy roads where the sport’s first dusty chapters were written? The trained mechanic won the Targa Florio in 1910 and set speeds just short of 100mph on his Indy 500 debut in 1914. His legend was set as he chased a French GP hat-trick in 1914. Against a trio of Mercedes, his ego drove him into single-handed combat that left him weeping when his Peugeot finally cried enough on the last lap. Two years later, he picked another unwinnable battle, a lone dogfight with enemy planes above the Western Front.

24: Gian Carlo Minardi

Far more than an F1 outsider

“I spent an amazing 21 years in F1 and the difficult moments I don’t remember. The beautiful ones I do!” said Gian Carlo Minardi in a rare interview with this magazine in 2013. He never did learn English, so beyond Italy, Minardi was sometimes dismissed as a peripheral F1 figure, just like his minnow team. But when the name finally disappeared from the grid in 2006 as the team became Toro Rosso, there was a genuine sense of sorrow. Beyond fantastic coffee, Minardi’s team offered flavour and character to the paddock, the boss a modern-day Don Quixote. Everyone loves an underdog and Minardi played the role with dignity and style.

23: Robin Herd

The designer who rocked F1

Much Advertised Racing Car Hoax. That’s what some unkindly folk reckoned March stood for, rather than an amalgam of the first letters of the founders’ surnames. But Robin Herd, youthful design genius and the heart of one of the world’s best production racing car manufacturers, proved them wrong right off the bat. Seemingly out of nowhere, his 701 grand prix car qualified first and second for its first F1 race, then won its next three. In truth, March never had it so good again, at least at the pinnacle, but through two decades Herd’s cars proved winners around the world, in F2 and F3 in Europe and emphatically during the 1980s in IndyCar.

22: Jo Siffert

Success in both F1 and sports cars

For Rob Walker, there was only one driver with whom he forged a bond close to the one he had with Stirling Moss. ‘Seppi’ first starred in Walker’s blue colours when he beat Jim Clark in the non-championship Mediterranean Grand Prix in 1965, but it was his famous ’68 British GP victory in a Lotus 49 at Brands Hatch that really fused the association. Then it’s in sports cars, specifically JWA’s Gulf-Porsche 917s, where he showed his true potential. His intra-team rivalry with Pedro Rodríguez and their famous side-by-side duel into Spa’s Eau Rouge was the stuff from which the era’s golden status shines. He died in a crash at Brands of all places, in the meaningless World Championship Victory F1 race of 1971, just months after Rodríguez succumbed at the Norisring.

21: François Delecour

WRC’s first flamboyant Frenchman

The Jean Alesi of rallying? It’s a cheap and easy comparison, but only because there’s probably some truth in it. Delecour shot into the WRC stratosphere with Ford in the early 1990s and soon proved to be more than just another French asphalt specialist. He hit his pinnacle in 1993-94 in the new and exciting Escort Cosworth, Delecour winning three rounds in the first season to finish as championship runner-up, then in ’94 clinched the Monte Carlo victory he’d chased for so long. Spectacular accidents, a flashing temper and a flamboyance amounted to cult-hero status above the world titles that might have been possible in the right car at the right time.

20: Bob Wollek

Endurance specialist

‘Brilliant Bob’: a nickname earned during three decades and 30 Le Mans starts. The touch and balance must have grown from the skiing that came first, before injury switched his focus. Famously, he would never win Le Mans; but, as with others here, such a glaring hole only added to his legend, even if four runner-up finishes, the last in 1998 for Porsche, surely stung. The 11 World Sportscar Championship race wins, four Daytona 24 Hours victories and a roster of other titles highlight the consistency of this campaigner. Wollek was still racing into the 2000s, only to be knocked off his bicycle and killed while riding from the track at the 2001 Sebring 12 Hours.

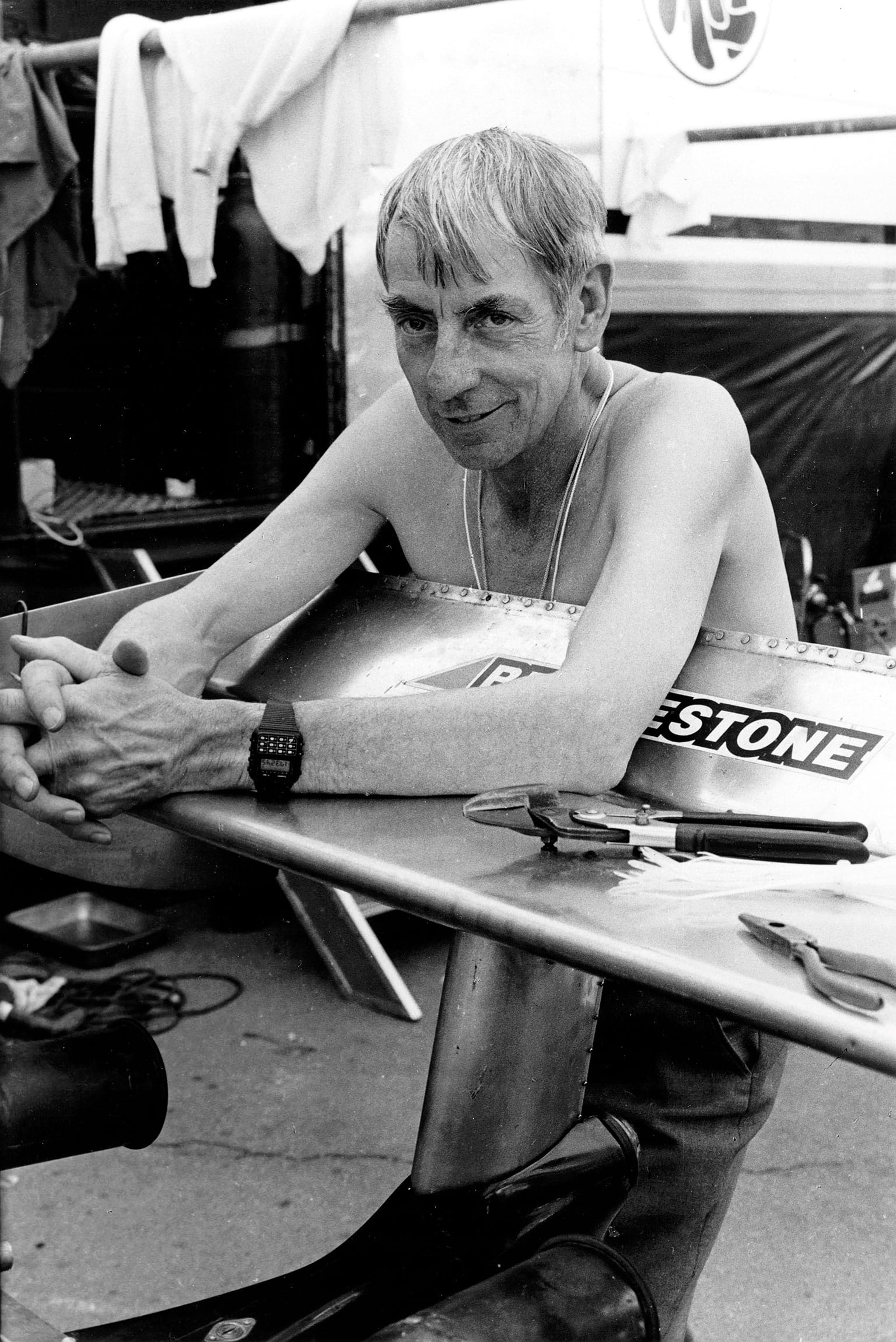

19: Ron Tauranac

19: Ron Tauranac

As well as being the man behind Brabham and Ralt, he was an inspiring engineer

Rory Byrne, one of the most successful racing car designers of the past three decades, credits Ron Tauranac as the man who inspired him. “I learnt a huge amount from working with him on the Ralt RT2 in 1979,” says Byrne. “He was an incredible engineer. He had such a wide engineering knowledge that I didn’t have. He was based just south of London and I was living in digs, working long hours like he was. He used to invite me home for Sunday lunch. A really fantastic and absolutely straight guy who called a spade a spade and was really helpful.”

That Byrne went on to design the Toleman TG280 that dominated the European Formula 2 Championship in 1980 says much about Tauranac’s selfless (some might argue naive) attitude that in this instance benefited someone who would become a direct rival. Tauranac, while famously abrupt and not a man to suffer fools, was no cut-throat businessman, which is why he sold Brabham so cheaply to Bernie Ecclestone and thereafter kept away from F1.

What he was, as Byrne says, was a brilliant engineer who designed some of the finest customer racing cars, under the guise of both Brabham and Ralt, over three decades. In partnership with Jack Brabham, Tauranac, who died in July, built racing cars that teams and drivers could depend on. The same principles remained when he worked under his own steam as Ralt, and a long list of drivers, from Mike Thackwell to Ayrton Senna, owed him a debt.

Ron Tauranac made his name working alongside Jack Brabham, hence each car’s ‘BT’ designation, before going solo and founding Ralt. Here, with Tim Schenken in the Brabham BT33 at the 1971 German GP

Getty

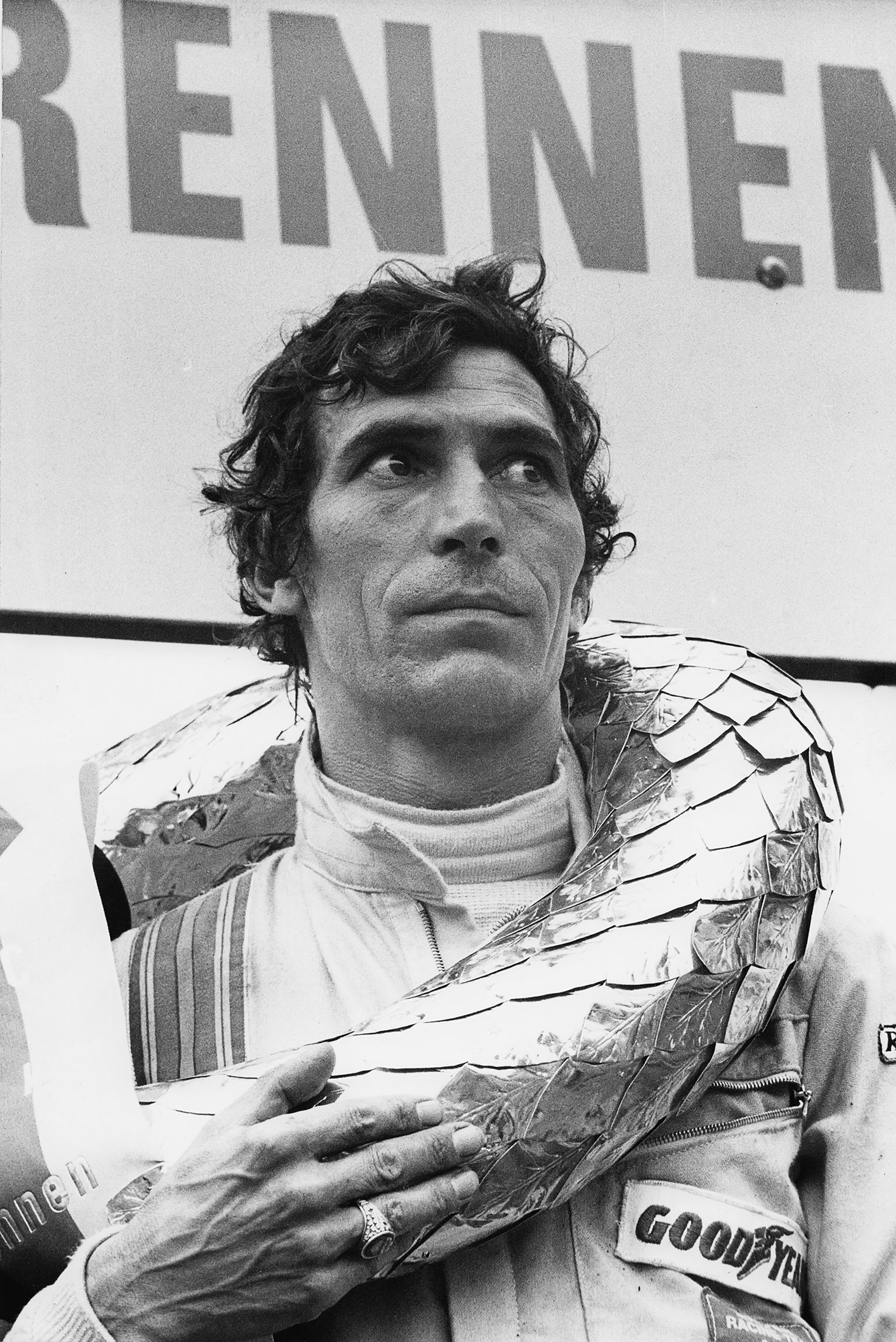

18: Ronnie Peterson

18: Ronnie Peterson

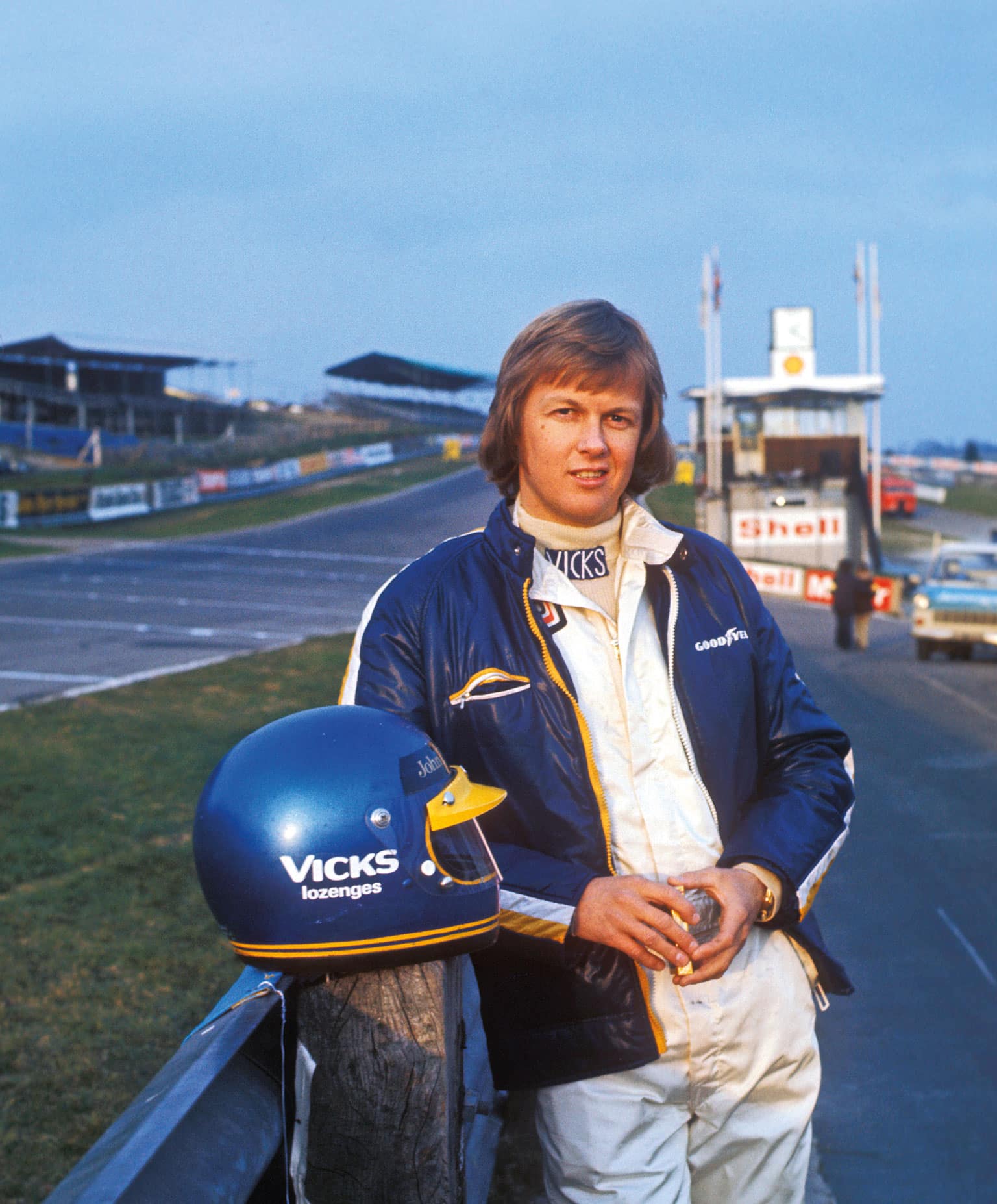

SuperSwede cut down in his prime

It’s all about the magic when it comes to ‘SuperSwede’: teetering on the edge through Woodcote in a Lotus 72; the blue skid-lid with yellow peak; the blond locks, quiet reserve and easy smile. For a generation, Ronnie Peterson represented the very best of motor racing. Sure, he fell short of becoming World Champion, but his liquid gold natural ability and press-on approach always meant more. Ronnie’s last season showed the best of him, in the Lotus 79. He accepted Mario Andretti was number one – if only in contractual terms. That they became solid friends under such pressure spoke volumes. After the tragedy of Monza in 1978, the champion knew what he’d lost: “There’s such a hole in racing now.”

17: David Purley

Courage and talent combined

Through the downhill sweepers after the pits at Rouen, Purley said he used to take a leaf from bayonet training in the Paras by screaming into his helmet to give him courage. Not that he needed it. None were braver than the man who desperately tried in vain to save Roger Williamson from his burning March at Zandvoort in 1973, an act for which he was awarded the George Medal. Purley’s most memorable moment in F1 was briefly leading in the rain at Zolder in ’77, only to earn the wrath of Niki Lauda for holding him up. After a huge accident at Silverstone, this daredevil raced again, then turned to stunt flying. He died flying his Pitts Special in 1985.

16: Gwenda Hawkes

Triumphed in a man’s world

A 1958 issue of Sports Illustrated said of British driver Gwenda Hawkes that she smashed speed records as some wives break dishes. Although Hawkes competed in races, including Le Mans in 1934 and ’35, she was happiest challenging records for speed and endurance. In 1935 at Brooklands she took the ladies lap record reaching 135.95mph in her Derby-Miller and was a regular at Montlhéry near Paris, taking the outright lap record of 147.67mph in 1934. In World War I, Hawkes was an ambulance driver on the eastern front and due to this was a stickler for appearance. Her mechanics wore pristine white overalls; it’s believed Hawkes footed the laundry bills.

15: Rodger Ward

15: Rodger Ward

An Indy and oval racing hero

A two-time Indy 500 winner and IndyCar series champion during the fabled roadster era, Rodger Ward is considered one of the great oval racers. With that in mind, it seems wrong that the first of his two appearances in an F1 grand prix should stand out for its ignominy – but that’s because he turned up at Sebring in 1959 in a Kurtis-Offy midget dirt racer with a two-speed gearbox. In fairness, he had just beaten a field of road racers at Lime Rock in it, but the United States GP was another matter. Still, it gave this racing raconteur plenty of ammo for stories, added to his experiences in Indycar roadsters that included victories at the 500 in 1959 and ’62. He died aged 83 in 2004.

14: Robert Kubica

Racing’s comeback king

When Robert Kubica scored his first grand prix win, for BMW in Canada in 2008, the easy prediction was it would be the first of many. Considered an equal among Lewis Hamilton, Fernando Alonso and Sebastian Vettel, what might this understated Pole have achieved had he kept away from off-duty fun in rally cars? The accident in a Skoda Fabia on the obscure Ronde di Andora Rally in February 2011 almost cost him his right arm, and his life.

A long and painful recovery followed, and Kubica’s fighting spirit eventually pulled him back to the sport that had almost killed him. Winning the WRC2 title in 2013 was dumbfounding, but when in 2017 he impressed Renault in an F1 test suddenly a miracle looked on. The comeback for the fallen Williams team was a wince-inducing anti-climax, but that should not tarnish Kubica. That he came back at all is more than enough.

13: Mark Donohue

The Can-Am legend who inspired one of America’s greats

Roger Penske’s friend and first racing ‘muse’ is always in the mix among the roll-call of great motor-sport all-rounders, given that he was comfortable in everything he got his hands on, most notably high-powered single-seaters, sports cars and Trans-Am ‘sedans’.

Mark Donohue emerged from the national SCCA scene to become a racing star, first with a Lola, then a Penske-run McLaren M6A. He lead Penske’s Daytona 24 Hours victory in 1969 with a Lola T70, won back-to-back Trans-Am titles and made an impression on his Indianapolis 500 debut, a race he would win for Penske in 1972 at just his fourth attempt. He won in NASCAR, dominated the 1973 Can-Am series in a Penske-run Porsche 917/30 that was so potent it killed the series, set a closed-course speed record and then was coaxed out of a surprise retirement by the ‘The Captain’’s offer to switch to F1.

Even with his formidable skills in developing racing cars, the Penske PC1 was uncompetitive in 1975 and the team switched to running a March. During practice at the Austrian GP, Donohue crashed through a barrier, killing a marshal, and suffered head injuries to which he succumbed two days later. For all the successes Penske has subsequently enjoyed through the decades, Donohue remains the team’s archetype of what a racing driver should be.

12: Derek Minter

A rebel on two wheels

Derek Minter only contested 25 grands prix in his career, but Mike Hailwood considered him the greatest rider he raced against. “For my money, out of all the names one could conjure with – Geoff Duke, Giacomo Agostini, Jim Redman and so on – the one that stands out as being the hardest of all to beat was Minter,” said Hailwood. Minter never took GP racing or factory teams that seriously, realising he could earn more cash racing borrowed machinery at home. In 1962 Honda lent him a bike for the 250cc TT and told him to let their full-time riders win. Minter ignored the order, won the race and never got another Honda ride. He didn’t care.

11: Tommy Byrne

A talent that wouldn’t conform

Was he genuinely faster than Ayrton Senna? The 1982 British Formula 3 champion certainly had a precious gift, but the reality was that rough-and-ready Irishman Tommy Byrne was never going to fit in the constrained, uptight world of F1. Too irreverent, too stubborn, just a shade too wild… F1 people like Ron Dennis, for whom Byrne famously tested in a fabled run in a McLaren at Silverstone, were always going to turn their nose up. Their loss – and ours. But such ‘what might have been’ stories are the stuff upon which motor-sport fans gorge. Byrne’s story, how he was ‘swindled’ out of an F1 future, then scraped his way into drives and a new life in America, is among the best.

10: Chris Amon

Ferrari’s unluckiest F1 star

Notorious for his awful luck and poor judgement on whom he should drive for and when, Amon should be remembered as one of the greats, not only of his era, but of any – despite that annoying albatross of never winning a championship grand prix. In 1968, in the wake of Jim Clark’s death, he was the fastest (even team-mate Jacky Ickx held his hands up), qualifying on the front row in eight of the 11 races. At least three wins were lost through unreliability. Clermont-Ferrand in 1972, when he dominated for Matra only for a puncture to rob him, was the killer blow. Charming, self-effacing and wonderful company. Wins and titles? They rarely tell the full story.

9: Kimi Räikkönen

Short on words, big on staying power

The 1000-yard stare, the refusal to play ball in interviews, the insouciance that can also be labelled plain rudeness… Kimi Räikkönen doesn’t give a damn, which is precisely why so many love him. But he must care about motor racing. The Finn has been an F1 driver since 2001, albeit with a short break to go rallying in 2010 after he was let go by Ferrari, then hired by Lotus in 2012, returning to the Scuderia in 2014.

It’s been a strange career, especially given that for long spells his performances have been average. But when he was good, Räikkönen was great: Suzuka 2005 – racing from the back to steam past Giancarlo Fisichella to win – stands as probably his finest moment. His 21st F1 win at the US Grand Prix in 2018 made him the only driver to win in the V10, V8 and hybrid V6 eras. He’s certainly persistent.

8: Dave Coyne

Formula Ford’s stand-out racer?

A car dealer who never was exactly snake slim, Dave Coyne could have been Michael Schumacher… Well, apparently he was high on Eddie Jordan’s list for Spa 1991 when Bertrand Gachot had been jailed, until Mercedes bankrolled the German into his debut. But as unlikely as it sounds, Coyne probably wouldn’t have been out of place. A prolific winner in Formula Ford through the 1980s, he nearly always astonished when he had a shot at F3 or F3000, in which he was particularly handy in the 1991 British series. Coyne’s greatest moment was his scene-stealing victory in the works Swift at the 1990 Formula Ford Festival, but it failed to lead to the big break he deserved.

7: Vic Elford

Race, rally, endurance… he did it all

With a face like the side of Snowdon and mental fortitude to match, Vic Elford represented British versatility on track and stage in the 1960s and ’70s. His first love will always be rallying, and it was largely thanks to ‘Quick Vic’ that Porsche discovered the 911’s competition gene. In 1968 he won the Monte Carlo Rally in one, crossed the Atlantic and stormed the Daytona 24 Hours in a 907. He then won the Targa Florio in heroic style after a puncture, and the Nürburgring 1000Kms. He always was handy around the ‘Green Hell’, as he’d proven on the gruelling 84-hour Marathon de la Route. He shone in 917s, yet never won Le Mans. But neither did Brian Redman.

6: Jon Ekerold

The fearless privateer who conquered the motorcycle world

Ekerold was the epitome of the brave, independent privateer that was the backbone of motorcycle grand prix racing in the 1970s and 1980s. The South African was fearless and only ever did things his way, which won him great support from fans who really knew what went on. His victory in the 1980 350cc world championship, against factory Kawasaki rider Toni Mang, was the stuff of legend. The pair went into the last race, at the 14-mile Nürburgring, equal on points. Ekerold won the title with an epic final lap, possibly the best-ever Nürburgring lap by a motorcyclist, which would’ve put him second in the 500cc race.

5: Stefan Bellof

The boy wonder who pushed the boundaries of sports cars

“Fast, fast, fast.” That’s how Hans Stuck describes his old Porsche Group C team-mate. Half a dozen years before Michael Schumacher broke through, most agree Stefan Bellof had it in him to become Germany’s first Formula 1 World Champion – with the right direction and in a team that could harness his raw ability. A Formula Ford contemporary of Ayrton Senna, Bellof broke through into F1 in the same year, most famously charging up behind the Brazilian in their wet-weather chase of Alain Prost at Monaco. Would he have won were it not for Jacky Ickx’s red flag? Irrelevant given that Tyrrell would eventually be excluded from the whole campaign over an alleged use of illegal ballast.

Whatever, Bellof and his team-mate Martin Brundle were full of youthful vim that 1984 season in the normally aspirated Tyrrells, but during ’85 tension would brew between Bellof and team boss Ken Tyrrell over his continuing dual campaigns in Group C sports cars. He’d first shone in ’83 driving for the works Porsche team, a stunning pole position lap around the Nürburgring Nordschleife in 6min 11.13sec standing as a beacon of his talent forever after. That he crashed spectacularly in the race with victory almost clasped in his hands was the other side of the coin with this effervescent charger. In ’85, now driving for the privateer Brun Motorsport team, Bellof went for an unlikely move on Ickx at Spa that ended in a head-on collision with a barrier. He didn’t stand a chance.

Just 22 days after Manfred Winkelhock’s death at Mosport Park, Germany now found itself mourning two of its brightest young sporting talents.

4: Ari Vatanen

Rally star who immortalised a hillclimb

Charming, urbane and almost once an FIA president, the contrast in Ari Vatanen couldn’t have been more stark whenever he climbed behind the wheel of a rally car. World Champion in Ford’s Escort in 1981, the Finn’s flamboyance was perfectly suited to the monstrous Group B era that was just about to dawn, and across ’84 and ’85 he won five rallies in a row in Peugeot’s 205 T16 – only to then suffer an enormous somersaulting accident in Argentina. How he survived and then recovered over the following 18 months is testimony to his remarkable competitive spirit.

Four victories in five years on the Paris-Dakar and that unforgettable short film Climb Dance filmed at Pikes Peak in the Peugeot 405 T16 all combine to make him an everlasting crowd favourite. Others won more rallies and titles, but few could match Vatanen’s aura and style.

Got five minutes you need filling? Give Climb Dance a watch and marvel at Vatanen’s control of the 405 Turbo 16

Villeneuve scored just six grand prix wins from his 67 starts, but he was about so much more than numbers. His exuberant driving style won him legions of fans

Getty

3: Gilles Villeneuve

The often-sideways Canadian who became an F1 revelation

“I must tell you, he was not dangerous for other drivers,” said René Arnoux, co-combatant in F1’s most famous duel, at Dijon in 1979 – for second place. “For himself maybe yes, but he was never happy in a straight line — he liked oversteer, the sliding. He had to race at the maximum, not 100 per cent, but 105 per cent.” That day, as the Ferrari and Renault slithered side by side, through and occasionally over the turns, Arnoux knew his rival was the only man he could trust this far over the edge. Gilles Villeneuve raced hard, relentlessly on every lap, but he also raced fair.

When you get to the nub, Villeneuve is what it’s all about. The cool little bloke in the slab-shaped Ferrari personified the perfect racing driver: flat out, edgy, brave, total faith in his own ability. He had the lot. Six wins, no world titles? That didn’t matter. In fact, somehow it’s better that way. The only thing that came easily for Villeneuve was his pure speed. Everything else he had to fight for.

The out-of-control lunatic is a lazy stereotype (although the hair-raising stories of his antics on the road sure don’t help the reputation). Those victories at Monaco and Jarama in 1981, the latter when he ‘managed’ a string of cars behind him in a hound of a turbo Ferrari, were the best of Villeneuve. Could he have been World Champion? He would have had a decent shot were it not for the red-mist madness of Imola that spilled over to that horrible day at Zolder in ’82.

But this was a driver living out of his time: he should have been born earlier, to race in the 1950s and ’60s when perhaps his sense of fair play might have served him better. Then again, perhaps he was just driving for the wrong team. Heresy! But the Old Man’s machinations were destructive for such a man. This side of the sport was one thing – the only thing – Villeneuve wasn’t equipped for. Had he raced for Williams or McLaren, with whom he made his unforgettable debut at Silverstone in ’77 and the team it’s said he might have moved to for ’83, he’d likely have thrived.

Jody Scheckter understood the team-mate who became his friend better than most: “For Gilles, racing was a romantic thing. My preoccupation was in keeping myself alive, but for him the thing was to be fastest, every race, every lap. I believe he was the fastest racing driver the world has ever seen. If he could come back tomorrow and live his life over again, I’m sure he would do it the same way, and with the same love. That was the right word. More than anyone I’ve known, Gilles was in love with motor racing.”

The golden boy of an evil empire, an unearthly talent lost too early, or both? Bernd Rosemeyer’s story is one of the most fascinating from perhaps the sport’s most turbulent time

2: Bernd Rosemeyer

One half of a pre-war power couple, and a fine racing driver of a conflicted era

Cult hero or hero of a cult? It might seem somewhat uncomfortable to the wider world to deify a man whose career was sponsored by the most evil regime in human history.

The Nazi influence casts a long shadow over 1930s grand prix racing, but its darkness still can’t mask the mesmerising motor sport that came out of this murky era. Mercedes-Benz, Auto Union and the brave aces who drove for both carry the blemishes of association, but to ‘cancel’ them, to borrow from modern parlance, would be a mistake. We’d lose too much to brush away one of the sport’s most important, influential and exciting decades.

Bernd Rosemeyer is among the most fascinating figures from the time, frozen in black and white, forever young with his dashing good looks. In a hotel at the 1980 German GP, Gilles Villeneuve was intrigued when an elderly gentleman told him he put him in mind of Rosemeyer, and so the comparison stands: fast in an otherworldly manner and beyond brave – too much, it seems, for either to live into old age.

Rosemeyer’s star shone bright, but burned out in a few years. Signed by Auto Union for 1935, he made his debut at deadly AVUS. That would have been daunting for anyone else. At the Nürburgring’s Eifelrennen he passed Rudi Caracciola’s Mercedes and even if he didn’t win, he’d served notice that here was the man around whom Auto Union’s challenge would now be centred. The pair would become intense rivals, the younger man aiming to dethrone the established master, but with a charm that won over all who would meet him. And the whole nation.

At the final race of 1935, the Czech GP, Rosemeyer took his maiden win and met his future wife Elly Beinhorn on the same day. Germany’s answer to Amy Johnson was then more famous than he, but together they became society’s most famous couple. While their romance drew attention, Rosemeyer went to work, dominating the 1936 season to become European champion. On the Nordschleife he won both the German GP and the Eifelrennen, the latter against Tazio Nuvolari’s Alfa Romeo in dense fog, driving a 520bhp six-litre V16 that would shoot him into a permanent place in the racing firmament. But such success also brought unwanted attention. He was made an Obersturmführer in the SS, but he point-blank refused to wear the uniform. Those who knew him insisted he was no Nazi.

Rosemeyer scored what would be his final GP victory at Donington in 1937 and then embarked on the fateful autobahn record runs dreamed up in a twisted nationalist zeal to showcase German superiority. In October he would set new records at 242.09mph for the mile and 233.89mph over 10 miles – think about that for a moment. But on January 27, 1938 his streamlined Auto Union was caught by a crosswind at 280mph. How pointless. He was just 28 years old.

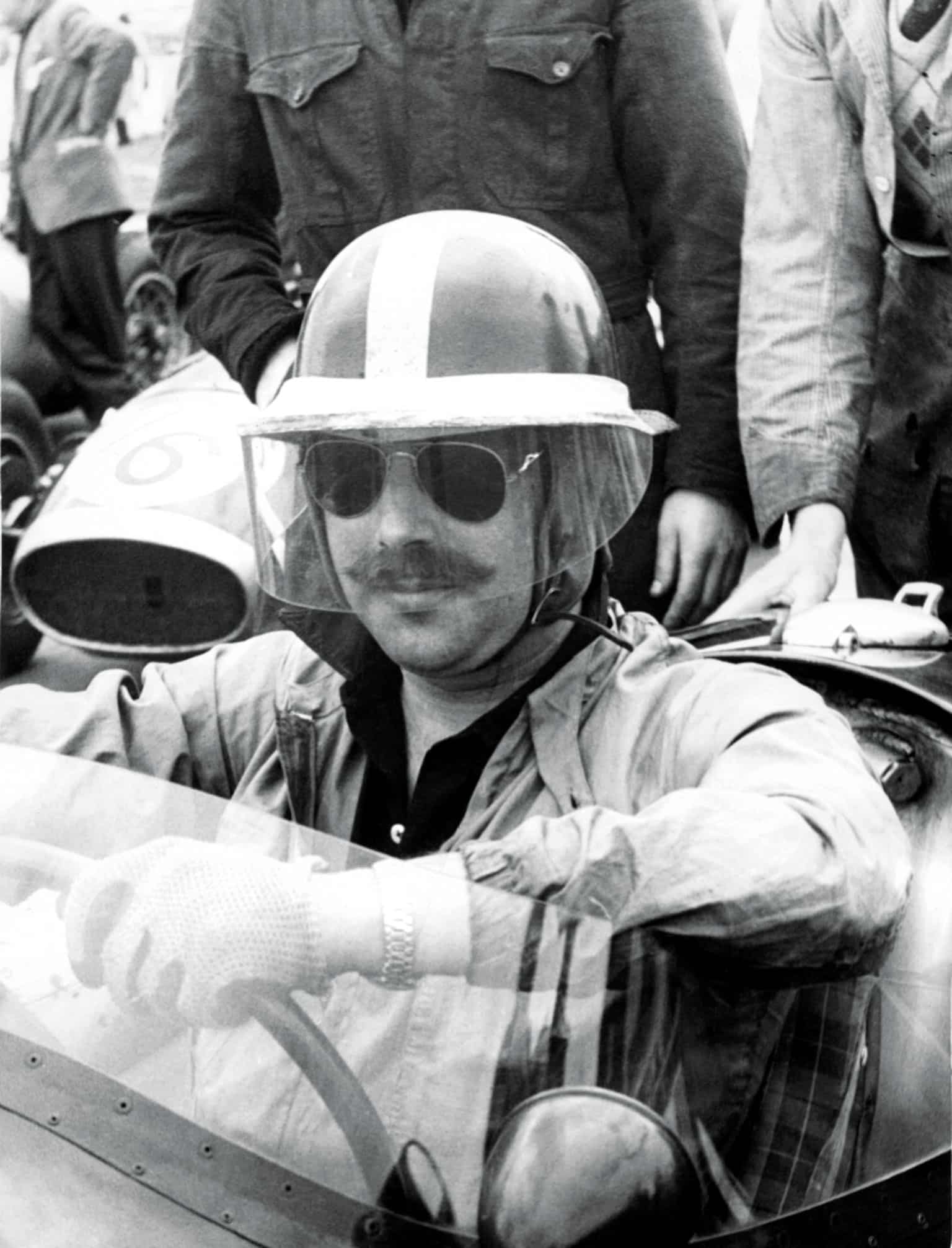

1: Jochen Rindt

The posthumous world-beater who will always be 28

There’s something about these so-called ‘cult heroes’. It’s certainly not true for all of them, as our collection highlights, but a high percentage never got to go grey, bald or gain a belly. Those that didn’t make it remain as they were in their prime, in photos, on film and in our minds. To us, and sadly to those who knew and loved him, Jochen Rindt will always be the guy with the unkempt hair, looking cool in his shades and Gold Leaf overalls, having a chuckle with his mate Jackie Stewart or with beautiful wife Nina on his arm. He’ll always be just 28 years old.

It’s not how he died that should be remembered, 50 years ago this autumn, it’s how he lived that mattered. Turn the page and David Tremayne will take you, with the help of old friends who knew the man, behind the cult-hero image. For all the myth-making around a career such as his, the truth is always more fascinating.

Who is your cult hero?

This year’s Hall of Fame will celebrate our cult heroes and give readers the chance to vote for their favourite. The annual Motor Sport Hall of Fame awards celebrate the best of the best in categories including F1, Sports Cars and Motorcycling. Past winners include Ayrton Senna, John Surtees and Jim Clark. For 2020, a shortlist of nominations from our Cult Heroes list will create a new and unique category. To have your say, cast your vote below. The winners will be inducted into our Hall of Fame in December.

19: Ron Tauranac

19: Ron Tauranac 18: Ronnie Peterson

18: Ronnie Peterson

15: Rodger Ward

15: Rodger Ward