The Secret Life of Stirling Moss

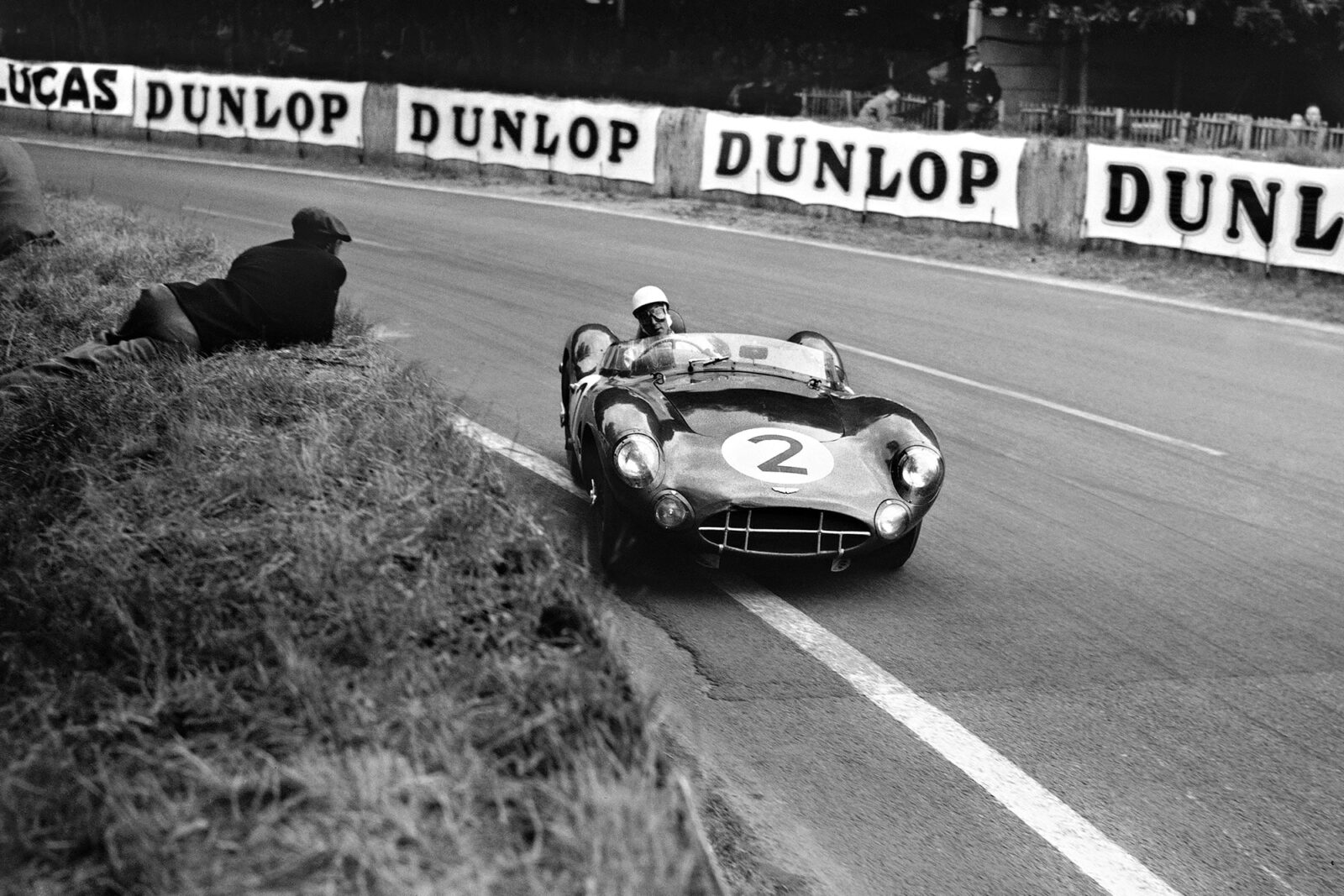

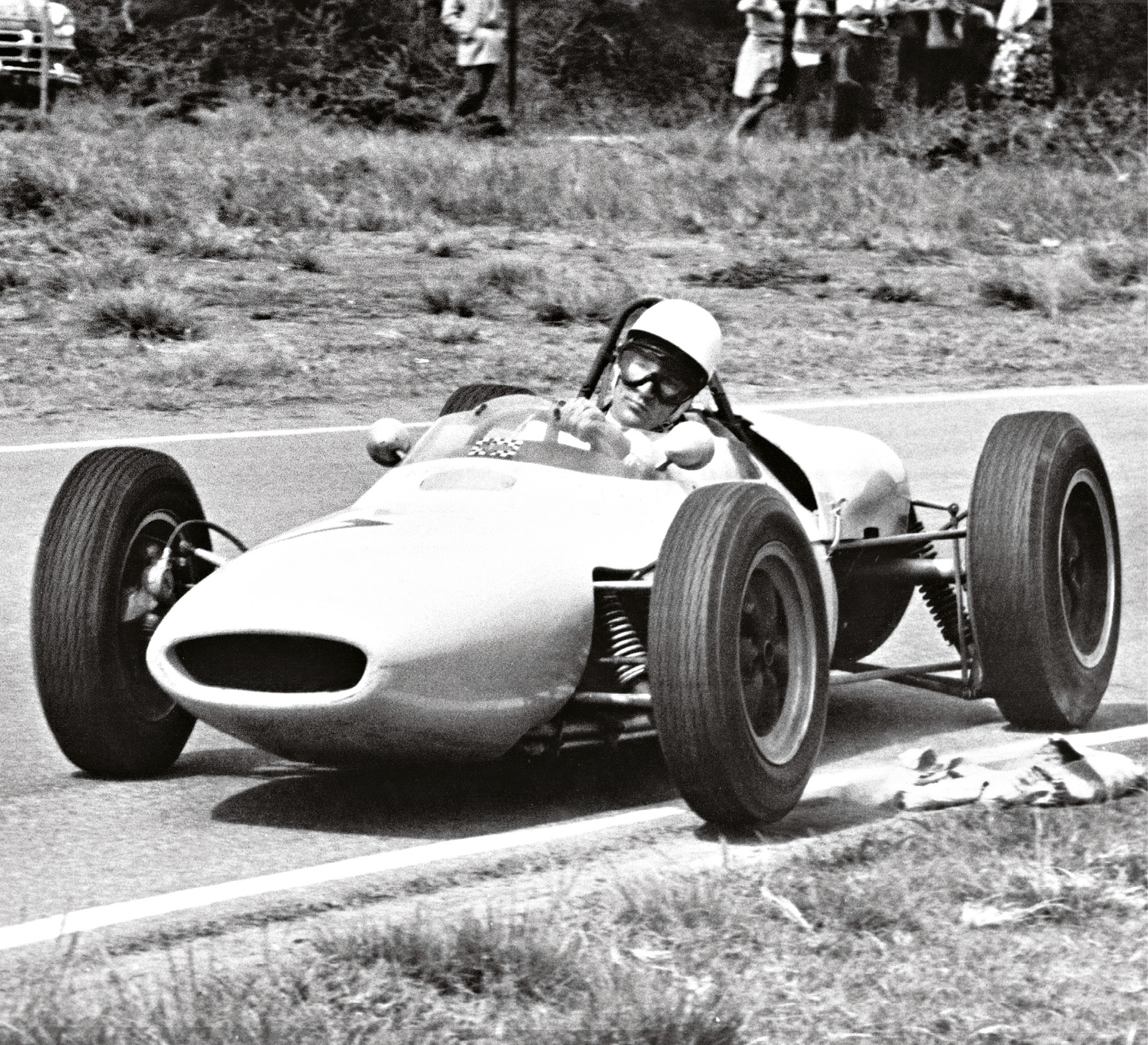

Moss as most know him best, at full flight in an Aston Martin DBR1 at Le Mans in 1958. But he was seldom far from full throttle away from the track, either

When 17-year-old Val Pirie answered an advert for a secretarial job in 1958, she little knew her employer would be the famous Stirling Moss, at the height of his career. Impatient and demanding as her new boss could be, Moss and Val grew close as over the years she became Girl Friday, chauffeur, confidante, house-building overseer and racing team manager, as well as helping him through the aftermath of his terrible accident. We present extracts from her memoir of her time with the Maestro, her friend of 60 years.

FLYING INTO ACTION

Thrown in at the deep end, Val is learning to handle her new boss’s hectic life – and impatient character.

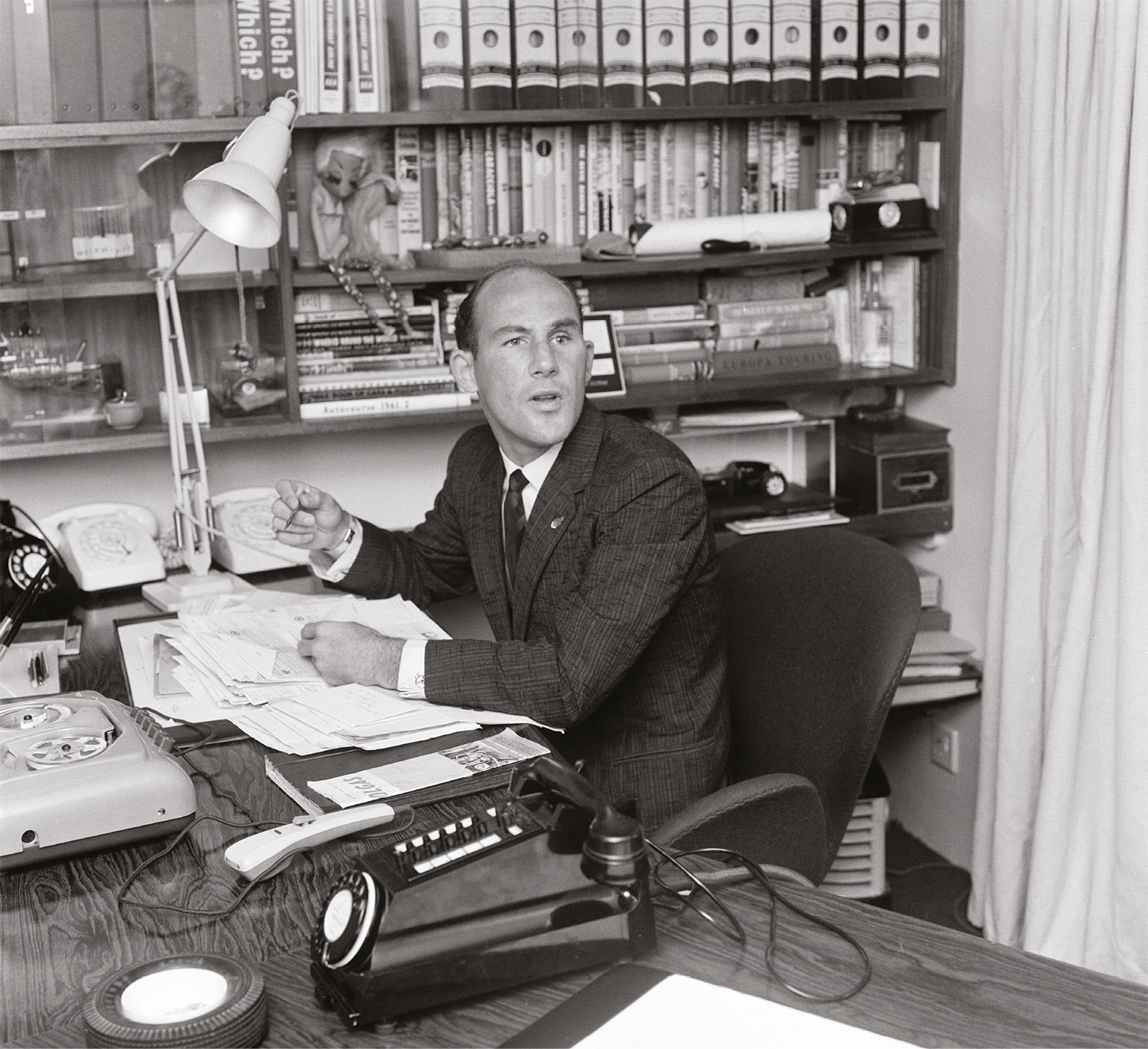

My geography was beginning to improve by leaps and bounds. For example, I had never heard of places such as Catania, AVUS or Riverside, let alone tried to arrange flights and accommodation for any of these places. In early August 1960, I received a very irate telephone call from Stirling. He was steaming with rage and there weren’t any niceties when I answered the phone.

‘Get on to that bloody airline and tell them they have to get me to Karlskoga in time for me to race there,’ he said bluntly down the line. ‘I don’t care how they get me there but tell them that if I do not arrive in time for me to race, I shall hold them responsible for paying my start money. Ring them now and tell them that I am stuck in the wilds of I can’t remember where and tell them to get me a flight out of here.’ The phone went dead. I looked at the receiver in my hand, wondering where to start.

Karlskoga was one of those places I didn’t know either, and after checking all the details of his journey, I telephoned the airline concerned with a watered-down version of his plight. The person at the other end of the telephone chose to act dumb, so in the end I demanded to speak to a manager. Another rather bored voice came on the line and when he heard what the problem was said, ‘And what do you expect me to do about it?’ to which I agitatedly replied, ‘Get him there. I don’t even mind if you have to charter a plane for him, just get him there.’

Such was his celebrity status they must have pulled out quite a lot of stops because they did get him to the circuit in time and he arrived home one very happy bunny because he also won the race.

AN INCENDIARY IDEA

Stirling decides to build a new house on an old bombsite in Mayfair.

Stirling was negotiating to acquire a 25-foot frontage on the old bombsite at the top end of the Shepherd Street cul-de-sac, two or three doors up from where we were, with a view to building a brand-new property for himself on the site. It was to be ultra-modern and, once again, it would incorporate his office so that he wouldn’t have to waste time travelling to work. He had found it to be so convenient having his office within his house that this would be a mandatory requirement in the new one as well.

Again, an enormous amount of research took place as to the most up-to-date, modern designs and appliances available on the market to suit his taste for the new place. Now he became entirely focused on the new building site, and spent all his spare time working on the plans for his new house.

Whenever he wanted to buy a particular oven, faucet, basin or even a roll of wallpaper he would contact the manufacturer direct – and ask if they would provide the products free of charge in return for the use of his name in publicising them once the house had been completed, and he used to spend hours on the telephone negotiating with all the various companies. Occasionally, if he really did want an item and if the chosen firm wouldn’t play ball with him, he would suggest paying a proportion of the cost or, if this failed, he would go and find an alternative supplier who would play ball. Again, I never felt comfortable with this, but Stirling didn’t have any qualms about it whatsoever. Neither did he have any qualms about returning goods that he had bought, although most of the time muggins here was generally sent to do this chore. I loathed it and always felt most embarrassed.

Stirling managed to persuade the Sunday Times to agree to sponsor a couple of features on the house once it was finished and this was the bait he always used in his negotiations, but this was of little use when negotiating with companies in America, from where he brought in a huge amount of hardware.

Once the land had been acquired, he had to find an architect who would work with him, but the relationship soon deteriorated when the appointed person told Stirling he was not prepared to be at his beck and call morning, noon and night…

TIME IS OF THE ESSENCE

A timely example of generosity with an ulterior motive, and a ‘balls to you’ riposte to Stirling’s impatient behaviour.

Another of Stirling’s quirks was punctuality. If I was driving him about I had to pick him up at the specific time he gave me and if I did not turn up on the exact minute there would be merry hell to pay, and I would be put under interrogation as to the whys and wherefores! It didn’t help either that I did not own a watch, so he decided to remedy this by buying me one when he was in Scandinavia and he gave it to me once he arrived home so that I would never have another excuse for being late again. Of course, this generosity was completely one-sided, because it would ensure that he could live his life according to his own standards and expectations.

Stirling had ensured the time clause was written into his contract with BP, in that when he went along to officially open garages for them he would only guarantee to stay and meet and greet and sign autographs until a specified time. Thereafter, he would only stay on longer at the rate agreed in the contract. He was, therefore, absolutely livid one day when he arrived at the Battersea Helipad from where he was to be flown to open a new BP garage in the south-west of England only to find that the helicopter had not arrived. He stormed back to the office and shot off a letter of complaint to the person at BP who had organised the tour and then, having partly relieved his frustration, tore off again back to the helipad. Not knowing any better at the time, I typed up what he had dictated, signed on his behalf and posted it.

He received his answer a couple of days later in the post in the shape of a confidential package of… ping pong balls! You should have seen the expression on his face when he opened it. It was a total mixture of frustration, irritation and, yes, actually a glimmer of admiration for such an ‘amusing’ and original reaction.

THE CHINESE CONNECTION

The night shift as Stirling’s chauffeur often involved a visit to Lotus – just not the one you might think.

Whenever I had to trundle out to the airport to pick Stirling up it was usually pretty late in the evening and nine times out of 10 on the drive back he would suggest going for a meal at the Lotus House Chinese restaurant on the Edgware Road, which stayed open until three in the morning, seven days a week – practically a unique phenomenon in London.

It was popular with other night owls, but generally we could sit there quietly and not be bugged by any autograph hunters. It was a peaceful place with subdued lighting where Stirling could relax, as much as he ever could, and unwind from the hustle and bustle of his life and come down from the satisfaction of winning his last race or brooding over why he hadn’t won it (and ultimately thinking about what more he could have done if he hadn’t retired for whatever reason).

Unusually, he would do most of the talking after I had updated him with office affairs and it was always about the mechanical stuff on his car; or he would sit there, having cleared a space on the pristine white linen tablecloth to work out which gear and axle ratios he would need for his next race and the like. It was all absolute double Dutch to me, but he liked to use me as a sounding board, albeit an ignorant one. I didn’t know anything at all about the mechanics of a car and never would. I wasn’t the slightest bit interested. That’s what mechanics were for!

He used to scribble away quite contentedly on scrappy little bits of paper and work out whatever was necessary, and he would be in his element, as happy as the proverbial pig in clover. We were in there eating shortly after I had applied for my provisional racing licence and he went to endless lengths to show me how to take the right line for some of the corners on the various circuits by drawing out the track and marking it up. He also wrote down the appropriate gears I should select for the bog-standard car I would first be driving on the various corners and straights.

BLIND DATE

Well before the days of internet dating, Moss plays matchmaker by introducing Val to a famous fellow Scot.

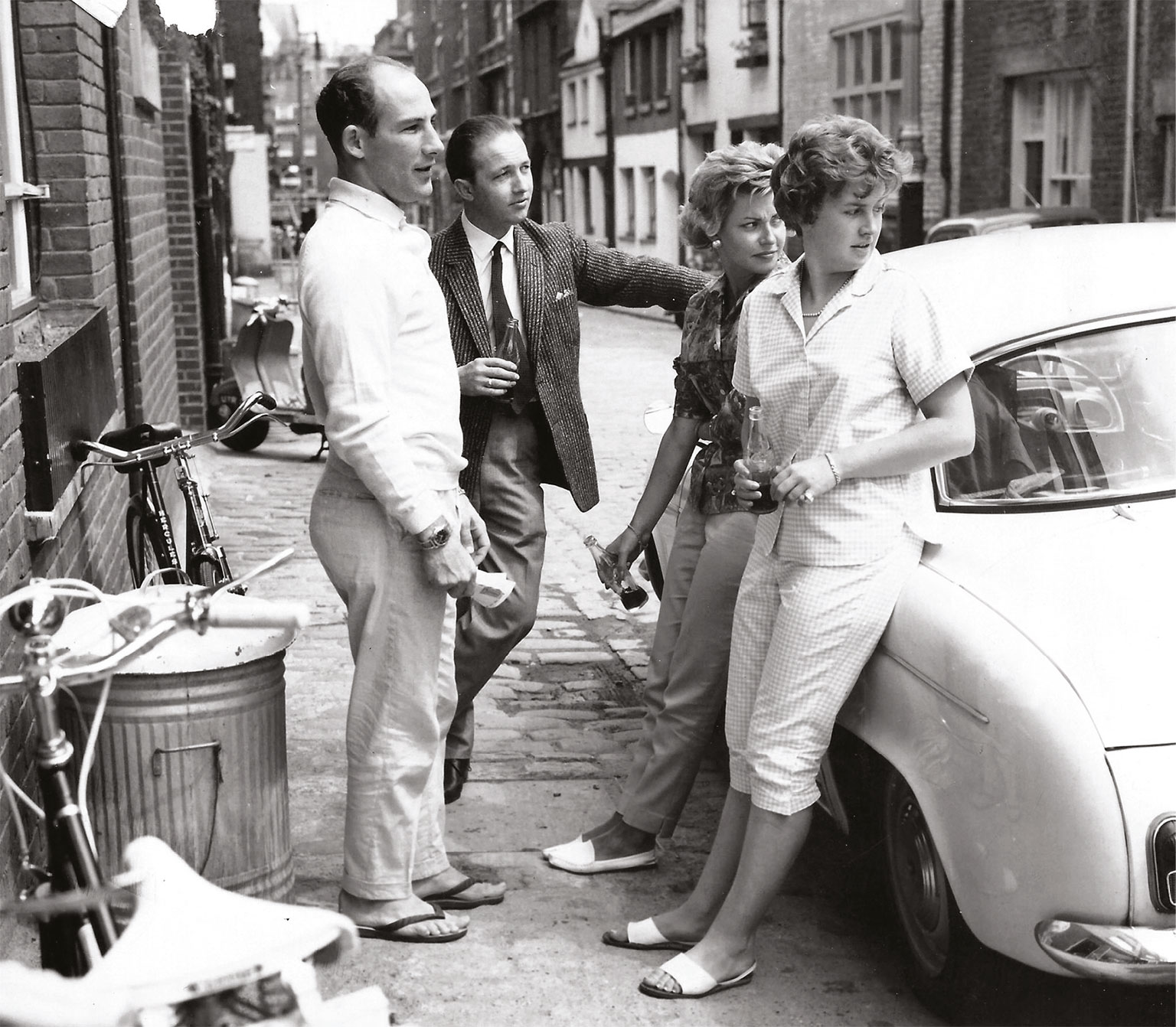

Around this time, I was going out on a lot on dates but there was no one special in my life and I was continually bugging Stirling to introduce me to some gorgeous fellow who would sweep me off my feet. Stirling’s thoughts were divided on the issue because he didn’t want to lose me, but neither did he want to be seen as if he wasn’t doing anything about it.

However, a new driving talent had emerged on the scene during the year and Stirling thought, as we were both Scottish, that we might just hit it off together and suggested to the young man in question, Jim Clark, that he take me along to the BRDC Annual Dinner in early December. Although we became lifelong friends until his death in 1968, he wasn’t for me or me for him. He was even shyer than Stirling, in fact, painfully so. He was a quiet, unassuming man, extremely bashful, but with a prodigious talent. He had a totally split personality because he loved his farming just as much as he did his motor racing. He owned a 1200-acre farm in Chirnside, Berwickshire, and coincidentally my mother also owned a house in Chirnside. Consequently, we fraternised quite a bit with many of the other people from the Borders who were involved in the motor racing scene.

The local garagiste and a leading light in the Border Reivers Racing Team, Jock McBain, owned a Doughty speedboat and, whatever the weather, we would all go water skiing in Berwick Harbour. Certainly, Jimmy used to come out of himself much more in his own surroundings and amongst his Scottish friends.

Stirling felt very relieved when he saw that we were not attracted to each other, but he was equally content that he had been seen to be trying to get me hitched up. He never really tried again. During his racing career Jimmy tended to drift into long-term relationships, but he did tell me that he would never get married until he had stopped motor racing – and of course, he never did.

A ROTATION OF DUTIES

Moss is seriously hurt at Goodwood in a terrible accident in April, 1962. For a month he remains in a coma.

The doctors recommended that someone from his inner circle should stay with him round the clock, preferably talking to him, to try to bring him round from the coma.

We formed a roster whereby I would do the 6:30am until lunch-time stint, when someone such as Rob Walker [his patron] or Ken Gregory [his manager] would come in to take over until I could get back to the hospital in the afternoon and wait for Alfred [Stirling’s father] to arrive around 10 in the evening. He would stay with Stirling overnight. I would then arrive back early in the morning to take over from Alfred, and so it went on, day after day.

“The public reaction to Stirling’s accident was absolutely overwhelming”

Initially, the hospital found it hard to cope with the unrealistic fuss and commotion associated with dealing with such a well-known and well-liked personality. The avalanche of mail, flowers and even people turning up unannounced to wish Stirling well was quite remarkable. We gave most of the flowers to the other patients in the hospital and I was, naturally, in charge of the mail. In addition, I also had the responsibility of seeing that the builders and suppliers kept up to scratch with the house.

The reaction of the public to Stirling’s accident was absolutely overwhelming. He was headline news for some time. No one knew quite how badly Stirling had been injured and we wanted to keep it that way, just in case. He was to be protected by a wall of silence, especially as far as the national press was concerned.

In the first couple of weeks or so, we received well over 1500 letters and cards wishing him well every day.

The rigid office policy of replying to every single letter received was strictly adhered to so this was quite a job, and every letter was personally signed either by Ken or myself. I could sit and sign and stamp these later whilst I spent time with Stirling in the evening before Alfred arrived. It also gave me something to talk to him about, even though at that time there weren’t any visible signs that he was listening to me. It was not exactly easy talking non-stop to a lifeless form, but it was an essential part of the recuperation process. Something had to trigger his brain out of its stupor.

SIGN OF HOPE

After weeks of bedside support, a familiar irritation finally stirs Stirling into his first words.

I found it rather tedious having to talk constantly non-stop to a virtually dead body. Consequently, I used to tell Stirling in detail what was going on at the house because I reckoned that that was his main interest.

Just prior to the accident, he had agreed to put in an internal vacuum system, but things hadn’t been going very well with it. A certain Mr Leon was the culprit; Stirling had been spitting fire and brimstone about him before the accident and I wasn’t doing much better with him after it.

“I just caught his mumbled words: ‘Bastar… Big bastaaar…d’”

I knew that this would really irritate Stirling more than most so, after I arrived at the hospital and having been told about the prospect of complete malfunction of the vacuum system, I began to tell him the story, whilst he lay there totally inert.

‘And, what’s more,’ I trilled, at the still, prostrate body, ‘that Mr Leon, he is a right little toad. He’s a s**t, a complete and utter bastard.’

By this time, I was pretty much yelling at the still, shrouded form when I suddenly heard a sound. I immediately stopped speaking, jumped up from the chair I was sitting on beside Stirling’s bed and looked at him. He was lying on his right side and I just caught the words as he mumbled: ‘Bastar… Big bastaaar…d.’

My heart jumped – this was typical of Stirling. That lifeless form had actually heard and said something. This was my first sign of hope for him.

Of course, his first words were officially attributed to his mother, Aileen, later that week when she visited him and claimed that he had said, ‘Mum’. It probably made for better reading in the press than ‘Bastard’!

A WEAK POINT

Val is now running the Stirling Moss Automobile Racing Team, which has prepared a Lotus Elan coupé for Sir John Whitmore in 1963

John drove the car to considerable success (as did I in some events, often quite unbeknown to Stirling), apart from the fact that its rear wheels were frequently flying off fairly early on in the car’s existence whilst John was racing it. This hub defect was, of course, a life-threatening predicament and Stirling became exceedingly angry and decided to do something about it. We had the hub metal tested by an expert and it was found to be not only made of very thin metal, but that the design was also flawed.

Without more ado Colin [Chapman] was summoned to Shepherd Street to discuss the matter with Stirling. He demanded that I should be present as well because by now I was virtually running the team by default because Stirling had very quickly become bored with it.

Colin sat in Stirling’s upstairs living room opposite us and Stirling told him in no uncertain terms that the car was exceedingly dangerous and that he was thinking of suing him. Colin tried to wriggle this way and that out of this somewhat tight situation, but really there was no room for manoeuvre.

He eventually agreed to pay a large amount of money to a charity specified by Stirling and, of course, to re-design all the Elan hubs and manufacture them using stronger metal.

We all shook hands on the deal. That was Stirling’s preferred way. Calmly, sensibly, with no rancour – and secretly.

Extracts from

Ciao Stirling – The inside story of a motor racing legend

By Valerie Pirie

Published by Biteback, £20

ISBN: 978-1-7859-0463-9

Occasionally, if you click a link to buy a product from a different website, Motor Sport may receive a commission on your purchase. This does not influence our editorial coverage.