The engineering concept behind these shrieking engines was straightforward: a two-stroke fires twice as often as a four-stroke does, therefore the four-stroke must rev twice as high. The 250 six revved to 18,000rpm, the 125 and 50 went to 21,000, compared to Yamaha’s 11,000rpm RD56.

Remarkably, these engines, and Honda’s first Formula 1 engine, the RA270, were mostly designed by one man, the brilliant Shoichiro Irimajiri, who was only 24 in 1964.

Irimajiri had wanted to design jets, but Japan was banned from engaging in such activities after World War II, so he joined Honda instead.

Honda itself was emblematic of Japan’s new role in the world. Metallurgist Soichiro Honda had established his company in 1948, by buying a job lot of World War II army radio generators and installing them in bicycles to create low-cost powered transport. By 1965 Honda was the world’s biggest motorcycle manufacturer, producing 1.25 million units annually.

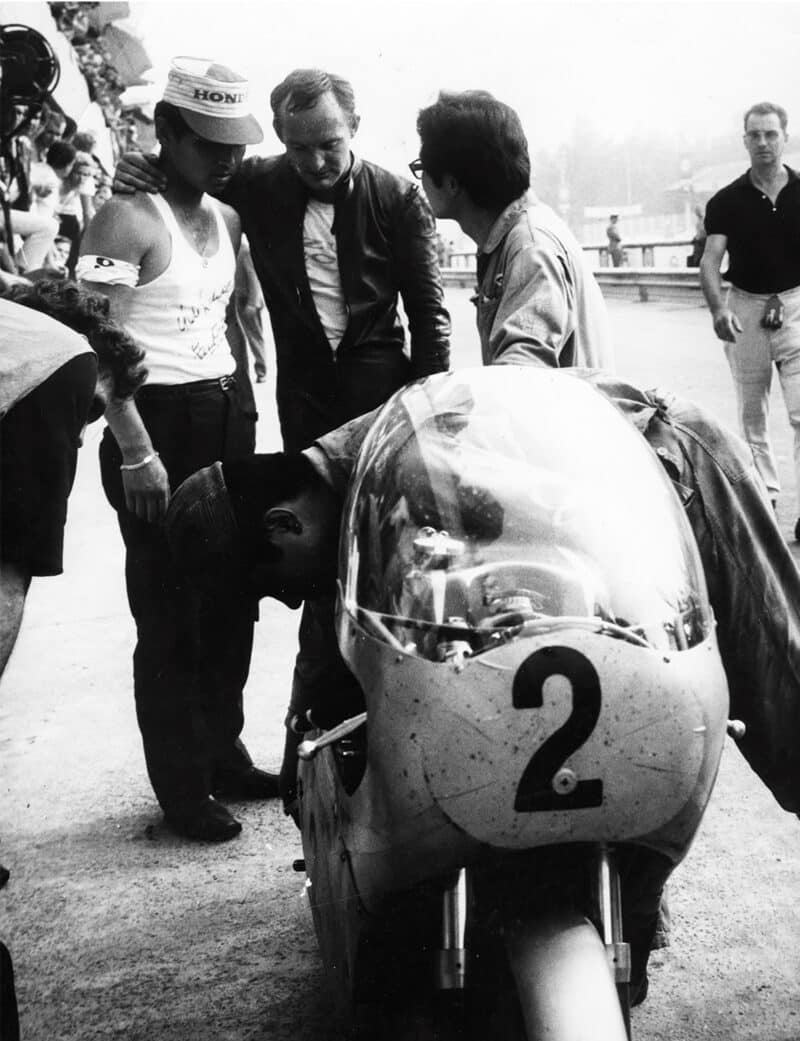

Jim Redman bumps Honda’s brand-new 250 six into life at Monza, September 1964.

Mustchler Woollett

Honda’s stunning growth was part of a greater Japanese economic boom that had been largely precipitated by the Korean and Vietnam wars, for which the US needed a supply and repair base close to these new theatres of war. During the first 18 months of the Korean conflict billions of dollars flowed into the Japanese economy, the Tokyo stock market leapt 80 per cent and numerous US-Japan licensing agreements were signed. Irimajiri was one of many Japanese engineers who took advantage of this new relationship between his country and the USA.

“When we had trouble with materials, we went to General Electric or Pratt and Whitney in the USA,” he recalls. “They asked us, ‘what problems do you have?’ We explained, and they introduced us to a very special steel, a new material they were using for turbine shafts. In those days American companies were kind to us; they showed us everything so we could overcome these problems. We took samples home, went to Daido Steel or Nippon Special Steel, who analysed it and then made the same for us.”

With his innate genius and imported knowhow, Irimajiri revolutionised four-stroke technology. His engines made up to 280 horsepower per litre, about the same specific power output of a 2019 MotoGP bike; although modern grand prix engines are restricted in bore size, specifically to rule out any Irimajiri-style flights of fancy.

No doubt many other four-stroke race departments learned from Honda’s engines. BMW certainly did. The details of Honda’s 1960s marvels were required reading for engineering students of that era, according to ex-BMW Motorsport head Mario Theissen.

When Aika and Redman arrived in Italy for the last race of the 1964 season their hand luggage caused a sensation in the Monza pit lane. “My heart sank when I saw its fantastic speed past the pits,” remembers Yamaha’s Phil Read, Redman’s rival for the 250cc world title. And the bike was so loud, with a shrieking exhaust note that sounded like the end of the world, that Dunlop tyre technicians refused to check its rear tyre while the engine was running.

When the race started Redman charged into the lead, but not for long. The six was far from fully developed, so its carburettors suffered a vapour lock, the mighty six slowed and the championship went to Read and Yamaha. It was another year or so before the bike was fully sorted, just in time for Mike Hailwood to arrive at Honda from MV Agusta. ‘Mike the Bike’ became synonymous with the six, taking the 1966 and 1967 250cc titles and the 1967 350cc championship, using a bored-out 297cc six.

Hailwood enjoyed these successes and many more despite his famous lack of technical nouse.

“Mike’s mechanical knowledge was practically zero – he didn’t have the remotest idea,” said fellow Honda rider Ralph Bryans, speaking before his death in 2014. “I was there when he jumped aboard the 250 six for the first time at Suzuka. He came back in and they asked him what it was like and he said, ‘bloody awful’. But as for what it was doing and what could they do to fix it – absolutely no feedback whatsoever. It was lucky there wasn’t much set-up to do in those days – there was only one tyre choice and we’d set the suspension at the start of the year and never touch it again.”

Although devoid of mechanical knowhow, ‘Mike the Bike’ could ride

Getty Images

At the Spa-Francorchamps track in 1966 Hailwood’s team-mate Redman suffered career-ending injuries. His place was taken by up-and-coming Brit Stuart Graham, who had sparked Honda’s interest with some brave rides aboard a single-cylinder Matchless G50 in 500cc grands prix. Honda approached the youngster at the East German GP, asking him to ride the 250 six in the quarter-litre class.

“Talk about jumping in at the deep end – going from a single-cylinder four-speed Matchless that revved to 7000rpm to a six-cylinder seven-speed Honda that they warmed up at 13,000rpm!” recalls Graham, who later raced saloon cars, enjoying great success in a Chevrolet Camaro. “It was pretty traumatic. Just riding the six out of the pits was a problem – it really had no flywheel, so it was very easy to stall. The power delivery wasn’t user-friendly – it was all way up at the top end and it came in with a big wallop at 15 or 16 thousand. And the handling was interesting, to put it mildly, because in those days all the emphasis was on the engine; the chassis was just somewhere to put the engine. All in all, it was pretty hairy.”

Irimajiri’s leitmotifs were high revs, low friction, lightweight materials, compact design and very clever combustion, using very shallow valve angles with almost vertical intake ports. The six was a stunning design – no wider than its four-cylinder predecessor – with tapered double-overhead camshafts that drove 24 valves, with sparks provided by special miniature NGK spark plugs. The crankshaft ran with one-piece conrods and tiny flywheels, with most of the mass concentrated towards the centre and drive taken between cylinders two and three, effectively halving the crank’s vibrating length.