Breakfast with... Niki Lauda

Eggs, toast, Vienna and one of the most distinguished figures in motor sport history: a perfect recipe

Niki Lauda: Been there done that

Many drivers have a corner named in their honour, rather fewer a breakfast. For those waking up in central Vienna, however, the ‘Niki Lauda Frühstück’ is a €21 option at the Café Imperial – creamy whipped coffee, a boiled egg, toasted local bread and natural yoghurt with fresh raspberries and stewed apple. It is so called because the Austrian has for many years started his day here whenever he’s in town – a perfect location, then, for an earlier-than-usual version of Motor Sport’s traditional ‘lunch’. The setting is grand, the mood informal. Lauda might be a national treasure – a three-time world champion who has played a key role in Mercedes’ recent run of F1 success (not least by persuading Lewis Hamilton to defect from McLaren) – but today he is simply a detail in rush-hour Vienna. Ever one to do things his own way, he has already eaten by the time we arrive so we sit and chat while tourists and businessmen choose between à la carte or buffet options. Many acknowledge Lauda’s presence and he responds to all with a nod and a smile. As the only diner wearing a sponsored red cap, he isn’t too hard to spot. “I always choose the same thing and have been coming here for many years,” he says. “It’s far longer than I care to remember – probably forever.”

Ladua at Casino Square at Monaco in 1975, en route to the first of five victories in a year that brought him the first of his three F1 titles

Motorsport Images

As a youngster, Andreas Nikolaus Lauda developed an interest in matters mechanical while helping out at one of his industrialist grandfather Hans’s factories. “From the age of about 12 I was fascinated by the tractors and so on and, as I was the owner’s grandson, they’d let me drive. One day a guy said to me, ‘When it snows, come here at 5am and you can use the plough.’ I’d do that for a couple of hours, until the factory opened up, and clear all the roadways. After that I wanted to drive the trucks – big things with long trailers. I was told to turn up at 4am, because they’d be on the road at 4.30. They said I could drive, but only in the dark because once it was light the police would spot me. As soon as the sun came up, I had to move aside and let the official driver take over. I guess I was 16 or 17 by then.

“I also picked up a VW cabrio for next to nothing in Vienna – it was a wreck when I bought it, but I took it to my grandfather’s place and made a ramp – I wanted to see how far I could jump, but after a few attempts the shock absorbers came through the top of their mountings so that was that.”

It wasn’t too hard to see how this might develop…

“I used to watch racing on TV,” he says, “and one of my uncles did some karting. Whenever he bought a new chassis, he used to take me along and ask me to run it in – I just had to drive around at a constant 3000rpm, no more, no less, and I think he was impressed that I did as I was told. He also took me to the Nürburgring to watch the German Grand Prix. It was wet and miserable, the year Jochen Rindt finished third in a Cooper-Maserati [1966]. While we were there I was introduced to Kurt Bergmann, who built Kaimann Formula Vee cars.”

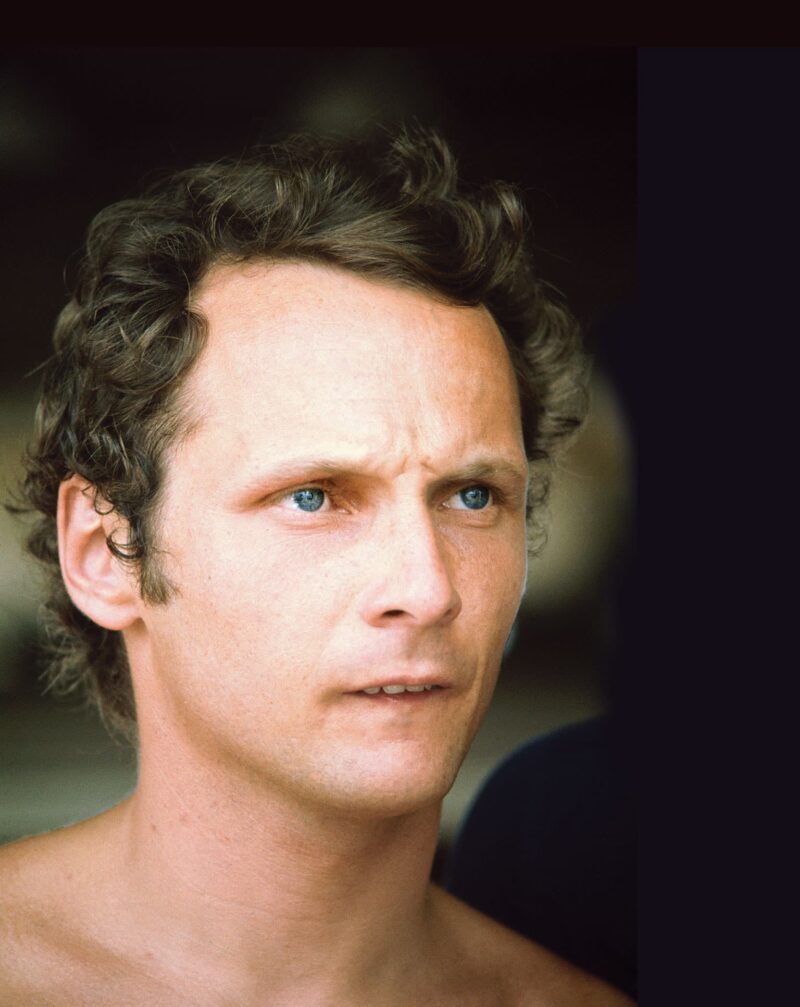

Lauda in his younger years

Motorsport Images

The Lauda family’s wealthy background enabled Niki to make a start in the sport on his own terms, initially with a Mini Cooper S from 1968: funds weren’t bottomless, but strong results led to him being offered drives. “My parents were fairly neutral and let me race,” he says, “but my grandfather was absolutely crazily against it. When I was 18 I moved from Vienna to Salzburg, living on my own, and started having some success in touring car racing. I renewed my association with Mr Bergmann in 1969, driving in Formula Vee, then tried F3 with a McNamara, though that was a disaster.” After a series of mishaps, he switched to sports cars and took a victory at Diepholz in the Bosch Racing Team’s Porsche 908.

IN 1971 he scored several points finishes in European F2, at the wheel of Bosch’s March 712, and made his Grand Prix debut on home soil at the Österreichring, again in a March. He qualified next to last, more than 6sec off the pace, and dropped out early with handling problems. “That was a one-off because the organisers wanted an Austrian in the race. They organised everything, but the result didn’t deter me because I knew it was a shit car. Later in the year, Max Mosley asked whether I wanted to do F1 with March in 1972. I needed to find 2.5 million schillings to secure the seat and the CEO of a bank agreed to loan me the money, but then called to tell me there was a problem because the deal had to be approved at board level – and that involved my grandfather. When he found out that I was ‘his’ Niki Lauda he said ‘no way’. He refused to approve it, so I went to see him and said it was none of his business if the bank was happy to lend me the money, but he told me I should be working in business and not getting involved in a stupid, dangerous sport.

“I now had a problem, because I’d signed a deal with March but had no money. That’s when I went to a rival bank, Raiffeisen, and explained that I had an opportunity to enter F1. The guy in charge asked what would happen if I died in an accident. He wanted me to take out life insurance, which I did, so they agreed a five-year, interest-free loan, which I eventually paid back, and that got me into March. It was a tricky time, because if I hadn’t been able to repay I’d have been in serious trouble, but I had no choice if I wanted to get into F1. I was eventually able to repay it…”

Lauda has never regretted withdrawing from the 1976 Japanese GP, but feels he made a mistake leaving Ferrari a year later

As his F1 career began to take shape, Lauda continued to compete in sports and saloon cars. In 1971 he won the second round of the European 2.0-litre Sports Car Championship at the Salzburgring, in a Chevron B19. “The organisers wanted me there and sorted out the car,” he says. “I’d never previously driven anything quite like it, but I really enjoyed the weekend because Helmut Marko was the series benchmark in his Lola and I beat him. I still sometimes remind him about that…” He finished third in that year’s Nürburgring 24 Hours, sharing a BMW 2800 CS with Günther Huber, took fourth place with Jody Scheckter in the 1972 Kyalami 9 Hours, won the opening round of the 1973 European Touring Car Championship at Monza (with Brian Muir, BMW 3.0 CSL) and raced works Ford Capris several times in the 1974 ETCC, even though he was by then with Ferrari in F1. Contracts were a little less proscriptive in those days…

And besides, he needed extra work where he could find it because his early days in F1 were a struggle. He won the 1972 John Player British F2 title and finished fifth in the European equivalent, but at the sport’s top tier the March 721 wasn’t terribly effective (ditto its 721G and 721X evolutions). Lauda failed to score a point and team-mate Ronnie Peterson, second in the championship a year beforehand, slipped to ninth.

“Max Mosley called late in the year, told me the team was running out of money and that there wouldn’t be a seat for me in ’73. This was November, so most of the deals were already done and it looked as though there’d be no way I could continue – and I still had that loan to pay off. So I called Louis Stanley at BRM and told him I might have a sponsor if there was a car available. I met him at an airport and was accompanied by the financial director of the bank that had lent me the money. He couldn’t speak much English and Louis spoke no German, so I translated between the two. It was basically two hours of bullshit on my part, but in the end we struck a deal and Stanley agreed that I could pay the first instalment of my sponsorship in Monaco. I knew I had no money, but had to find some way of getting in the car.

Lauda in action with McLaren in 1984

Motorsport Images

“During testing at Kyalami I was quicker than my team-mates Beltoise and Regazzoni, so Clay asked if he could try my car. We swapped, I adjusted his car the way I felt it should be and was still quicker, so was performing well against a couple of experienced drivers. When we got to Monaco I was running third, ahead of Jacky Ickx’s Ferrari until I retired with a gearbox problem. That evening Stanley said to me, ‘Let’s sit down at the Hotel de Paris and talk.’ Over dinner he said, ‘D’you know what? You don’t need to pay money any more, because your performances have been outstanding. You just need to sign a contract for 1974 here and now.’ I was happy with that, signed and returned home.

“At the time my cousin’s secretary also worked as my PA and we had a little joke between us. I’d always say, ‘Let me know when Ferrari calls.’ On the Monday after Monaco I got back and she said, ‘Ferrari called…’ I didn’t believe her, but she insisted that Luca di Montezemolo had phoned. I rang him and he confirmed that the Old Man wanted to see me, so I drove down to Maranello. Ferrari wanted me to sign, because of my Monaco performance. I told him that I’d love to, but that I had just committed to a new deal with BRM. He said, ‘Don’t worry about that, I’ll fix the legal issues.’

“It was a risk because at that time Ferrari was a bit of a disaster – but when I saw the facilities at Fiorano, with the circuit and all the other technology, I couldn’t believe that they weren’t winning. Nobody else had a set-up like that and as soon as I saw it I decided to sign with them.

“Dealing with Enzo Ferrari was both easy and difficult. If he liked you it was fine, but you had to earn that. When I first drove the car at the end of 1973, in testing at Fiorano, it was understeering terribly and didn’t work. I told them the car was shit. I was advised not to say that because I’d get in trouble with the Old Man, but it simply didn’t work and I told him as much.

“He asked how much quicker I could go if they sorted the front end and I replied ‘half a second’ – I probably should have said three tenths, but once Mauro Forghieri had revised the front suspension I found eight and from that moment I had Mr Ferrari’s respect.”

It took just four races with the team for Lauda to secure his maiden F1 success, in the Spanish GP at Jarama. “The conditions were slippery and difficult,” he says, “I could see Montezemolo standing next to the race director for the final three laps and wondered what the hell he was doing, but he was apparently trying to get the race stopped while I was still ahead! That evening I received a phone call in my hotel room from Emerson Fittipaldi, whom I didn’t know well at that stage. He told me that the first win was always the most difficult and that the rest would come easily – he was right.

“I screwed up in 1974, though. I had a couple of spins and incidents, so wasn’t quite ready to challenge for the championship, but in 1975 I was quick and the car was perfect, so my first world title actually felt relatively easy. When I won that first race I suppose there was some sense of emotion, but as soon as it was over I was already thinking ahead to the next event. I always said to myself, ‘This is why I’m paid and this is what I have to deliver.’ I only worried if I didn’t deliver. I didn’t waste time thinking about how well I’d driven – even on the podium I’d be thinking, ‘Shit, what could I have done better today and what can I do in the next race?’ I never looked back at the past, just drew on the experiences I’d gained if I thought they’d serve me well in the future.”

Was there any reconciliation with grandfather Hans? “No,” he says. “I ignored him after he stopped that bank loan and unfortunately he died before I became world champion.”

Few had ever seen anybody with the sort of iron will of Lauda

Motorsport Images

The 1976 season has been well chronicled in Motor Sport. It was the year of Lauda versus James Hunt, their friendship tested by a close title contest that involved protests, counter-protests, disqualifications, reinstatements and the Austrian’s astonishing recovery from life-threatening injuries. Formula 1 made headlines at both ends of the newspapers and it was a season that paved the way to the sport’s adoption by mainstream TV.

Lauda’s decision to withdraw from the sodden Fuji finale enabled Hunt to sneak the title, but the Austrian insists he has never regretted his decision not to continue that day.

“At Fuji the rain was relentless,” he says. “As it was starting to get darker, they said, ‘Right, we have to race now because of TV.’ I thought it was idiotic – why hadn’t we started earlier when the light was better, because the rain was no different? This stupidity, because of TV, meant conditions were wholly unacceptable. And anyway, I didn’t lose the championship because of Fuji – I lost it because I missed three races after my fiery accident at the Nürburgring.

“I have some memories of that day. I recall walking to the funny old paddock and a German guy approaching for an autograph. I was in a bit of a hurry, but signed, then he asked me to date it. I asked why he wanted it dating and he replied, ‘It could be your last.’ I was stunned. ‘You think I’m going to die?’ ‘Could be,’ he said. I walked off without adding the date. I remember that, then the start, pitting to change tyres, rejoining the track… and that’s all.”

Has he ever revisited Bergwerk, where the accident occurred?

“Only once,” he says, “and it was many years later. I returned with [long-time F1 motorhome chef] Karl-Heinz Zimmermann, Bernie Ecclestone and one or two others. They thought I should go back to celebrate my survival with a glass or two of schnapps. While we were there, three Germans came past and spotted me, ‘Hey, it’s Niki Lauda… What are you doing here?’ Karl-Heinz replied, ‘He’s looking for his missing ear.’ They were horrified by what they perceived as his disrespect – I thought one of them was going to hit him. He then whispered to me to go and look in the grass, where – and I didn’t know this – he’d hidden a pig’s ear that he’d brought with him. Five metres ahead I saw it in the grass, shouted, ‘Look, I’ve found it’ and the Germans went away, now even more upset with our sense of humour…”

Lauda crashed on August 1 and was back in a car by early September, despite having been given the last rites on his hospital bed. “A nurse had asked whether I’d like to see a priest – and I nodded, because I thought any bit of help might be useful, but nothing really happened. He just touched me on the shoulder and left without saying anything.

“Returning at Monza shouldn’t have been a problem. I felt fit enough and tested at Fiorano, to make sure my wrists didn’t hurt and that I could cope with any pain where my helmet was rubbing against damaged skin. Ferrari then called and advised me to miss another race, largely because he’d signed Carlos Reutemann and didn’t want to run three cars. I told him I had a f**king contract and was ready to go. He didn’t like that…

“I wasn’t bothered that the Old Man had signed Reutemann, because he hadn’t known when – or if – I’d be coming back, so he had to do something. But I desperately wanted to know if I could still do it and Fiorano had been positive, so I felt I could race again.

“When I got to Monza the organisers told me I’d need a medical check. I said, ‘What? I’ve had one in Austria – why do I need another?’ For half a day they bothered me, making me do tests – and I’m sure Ferrari was behind it because he didn’t want me in the car. The whole of Thursday was wasted, because I couldn’t speak to my engineers to get prepared for the weekend, but I returned on Friday, went out – and then felt as though I couldn’t drive. I’d experienced no fear at Fiorano, but now I was terrified. I stopped, went back to the hotel, thought about things and decided to treat Saturday practice as a test session. I asked the team not to show me any times – I didn’t want to be compared with Reutemann or Regazzoni, I just wanted to drive. I pounded around, not paying attention to anything else, and suddenly I was quickest of the Ferraris. I thought, ‘Shit, no practice on Friday and I can still blow these two idiots away… That’s not bad.’ My confidence quickly came back.

Lauda launched two airlines: Lauda Air, later sold to Austrian, and flyNiki, now part of Etihad. He also regularly captained flights

Motorsport Images

“On Sunday I had another problem, because I was sitting on the grid, looking for a man with a flag, didn’t engage a gear and then suddenly saw a light – nobody had told me they were using lights, so I made a terrible getaway and dropped to 10th or something. Then it started to rain, which made things difficult, but I fought back to fourth and everything felt fine again.

“At the end of 1976 I called Ferrari from Japan, told him of my decision to withdraw from the race and he said, ‘I respect what you’ve done, don’t worry.’ He seemed fine. I needed another eye operation, so was out of action for a month, then returned feeling ready to resume. I was told I could go to Fiorano to test some new brake pads. I said, ‘Why the f**k should I do that?’ and was informed that Reutemann was now heading our development programme at Paul Ricard. I argued backwards and forwards, pointed out that my contract made me number one driver and that I should be heading the test programme. The Old Man said, ‘It’s a simple decision – Reutemann will test.’

“I then asked whether my contract was still valid, to which he replied ‘yes’, and I told him if Reutemann was testing it meant my contract wasn’t valid – and that I had an offer to drive for McLaren instead. It was bullshit, because I’d never spoken to them, but I repeated that if he didn’t fulfil my contract then I could go to McLaren. I left the office and he later called me, saying he would respect my contract and that I could attend the Ricard test, but only on the last day. I went down and watched Carlos testing my car, then jumped in on the Saturday. Everything felt a bit worn out after three days of running, the gearbox was shagged – everything was shit. No matter. I drove a few laps, added a couple of holes to the front wing, changed the front springs – nothing major – and the car felt better, so I asked for a fresh set of tyres and went 0.6sec quicker than Reutemann had managed in three days. I jumped out and the team asked what I was doing. I said, ‘I’ve found out what I needed to know and you don’t want me to test anyway…’ That set off a Ferrari panic – ‘You should test, you need to test’. I said, ‘No, Carlos is the master of testing’ and went home. Forghieri then called and told me I was back in charge of development. That was fine and I won the championship, but I then left because I’d felt hurt about what had happened earlier in the year, the way everyone seemed to think I was finished – and also Bernie Ecclestone had made me an offer to join Brabham.

“Financially the terms were good, but looking back it was a mistake to leave Ferrari when I did – if I’d stayed maybe I could have won another championship. It was definitely the wrong thing to do.

“How was Bernie? If he was in a good mood we were friends, if he was in a bad mood I was his biggest enemy. It was always like that, but my relationship within Bernie was a bit like the one I had with Ferrari – lots of ups and downs, but with both parties I knew when we looked into each other’s eyes we had a proper relationship.”

Sacked by Renault, Alain Prost joined Lauda at McLaren in 1984, and lost the world championship to his team-mate by a single point

Motorsport Images

Lauda spent less than two seasons with Brabham, winning with the controversial BT46B fan car on its only appearance (Sweden 1978) and taking one other victory, being promoted from third to first in Italy that year after Mario Andretti and Gilles Villeneuve collected jump-start penalties.

“Towards the end of 1979 I was due to renegotiate my terms with Bernie – and he never wanted to pay anybody too much. I told him I wanted $2 million and he said, ‘You must be joking – the deal is $500,000.’ We battled for three or four months and he went around to all the other team principals saying, ‘Lauda wants two million – let’s not pay him. If one of us starts paying too much we’ll all be screwed.’ He told me he wouldn’t budge, but he also had to renew his team sponsorship with Parmalat, so we went together to see the boss Calisto Tanzi. He agreed to sign another deal, but I had to be one of the drivers. Bernie said, ‘Sure, Niki is staying.’ I then pointed out that I wouldn’t be driving, because Bernie hadn’t given me the contract I wanted. Tanzi left the room and told us to sort it out, otherwise he wouldn’t be sponsoring the team. Bernie looked at me, said ‘What do you want then?’ and I replied, ‘Two million, simple.’ When I eventually signed the contract after such a long fight, I wasn’t happy. I’d achieved something – the best ever pay packet for an F1 driver – but didn’t feel particularly good about it. Bernie said, ‘You’ve done a good job, you bastard’ – but was laughing when he said it. That was the relationship we had.

“That was just two weeks before Montréal, where we had a new car – with Cosworth engine – and everything looked promising. We’d got rid of the 12-cylinder Alfa and in theory had something more competitive, but when I looked out of my hotel window on the first morning it was grey, drizzly and I felt awful. I went to the circuit, got in the car and there was a real tickle in my back – I hated the vibration you got from the Cosworth. I started practice, went through the gears and then thought, ‘What’s happening here? I’ve had enough of this.’ It was like a curtain coming down, so I returned to the pits, checked tyre pressures, had a think to myself – did I really want to turn down two million from Bernie? – and then went out again. But the feeling did not go away. I got out of the car, went to Bernie and said, ‘We need to talk.’ He was the fairest guy I’ve ever met. He said he understood, but told me not to rush a decision I might regret, to go away and have a think – skip practice for the day, return to the hotel and consider. His attitude was great, but after a few minutes I went back and said, ‘Bernie, I’m sorry that’s it.’ He said, ‘Okay, fine – but do me a favour. Leave your helmet and overalls here because I need to find another driver…’ He gave them to Ricardo Zunino and I left.”

In 1979 Lauda had also won the inaugural BMW Procar title, driving in the F1 support series for Ron Dennis’s Project 4 team. “After I stopped I completely lost interest in F1,” he says, “and besides I was busy running my airline business. But Ron would call me every few months, just for a chat, and in 1981 I attended the Austrian GP and found I quite enjoyed it. Ron was by then in charge of McLaren and invited me to Monza, which I also enjoyed. All my bad feelings about the sport seemed to have disappeared. Ron called again after Monza and asked if I wanted to test at Donington. He caught me just as my interest was rekindled. I was out of shape because I hadn’t trained, but my times compared well with John Watson’s and Ron persuaded me to sign for ’82.”

He won the third race of his comeback season, at Long Beach, and again that summer at Brands Hatch. For two seasons he and Watson were closely matched – and then Renault sacked Alain Prost, just as McLaren was about to get its hands on the efficient, Porsche-designed TAG turbo engine.

“I’d tried to convince John to stay,” Lauda says, “but he and Ron were arguing about his retainer and then all of a sudden Prost was on the market. Who was Prost? I didn’t care. Fine. Sign him. Then we went to Rio and he was on pole, half a second quicker than me. F**k, he was fast. You had to turn the turbo up to double power for qualifying and I hated that – but he could handle it perfectly. I worked on my qualifying speed like you couldn’t believe, but if I gained two tenths so did he.

Lauda in 1979

Motorsport Images

“This went on for the first few races, so I realised I wasn’t going to beat him in qualifying and decided I had to try something else to get the upper hand. So from Friday I worked on race set-ups, ditto on Saturday, and in races I was generally in better shape, could look after the tyres and so on and ended up beating him to the title by half a point. It happened because I changed my way of attacking him, but the following year he won – and he was a difficult bugger because he was so quick, no question. He was definitely the next generation, so I decided it was the right time to stop again.”

Victory in the 1985 Dutch GP would be his 25th and last.

He remained a frequent paddock presence following his retirement, simply because he was in demand as a TV analyst – “I was running my airline business but always had work to do in F1. I would not have attended if I’d not been employed” – but there would be a consultancy role at Ferrari during the mid-1990s before he took a management position at Jaguar Racing during 2001, a fairly fruitless stint lasting little more than a year. He then returned to his TV work before resuming a hands-on role when Mercedes appointed him as non-executive chairman of its Formula 1 team in 2012.

“Jaguar had potential,” he says, “but Ford’s approach was too corporate. When I joined, the main accountant told me that this was a Ford company so I had to read the compliance book. I asked what it said, and he told me that if I took a sparkling mineral water from the hotel minibar I had to pay, but if I took a still water I didn’t. He told me to be careful not to make mistakes and insisted I read this book of compliance, but I didn’t. I just decided to pay my own hotel bills because I didn’t want to be bothered by Ford’s stupid rules.

“When they got rid of me – I was told I’d done nothing wrong, but they wanted to install British management – the compliance team asked to check my account. If there had been a single unaccounted bottle of sparkling water they might not have paid off my contract, but as I’d settled my own bills there was no account and they had to pay compensation.

“The most incredible thing was that I introduced Red Bull boss Dietrich Mateschitz to the team as a potential sponsor, but Ford decided the two companies weren’t compatible. I could never understand why: didn’t they want to sell Fords to young people?” By the time Ford pulled the plug at the end of 2004, Jaguar had recorded two podium finishes in five seasons; when Red Bull subsequently took over, it had become a race winner and title contender within the same time frame.

Lauda’s current management activities have been rather more successful, Mercedes having emerged as F1’s most potent force during the current hybrid era. “I attended my first board meeting as a guest in 2012,” he says, “and asked who was going to drive in 2013. Norbert Haug [formerly motor sport chief at Mercedes] seemed to think it was a stupid question and replied ‘Schumacher and Rosberg’. I replied, ‘Yes, but what if Michael wants to retire.’ I was assured he wouldn’t, but he didn’t have to let the team know until October – by which time all the main drives would be settled. I didn’t think it was a good idea to wait, made my feelings known and, as incoming chairman, was told to take over. I knew Lewis Hamilton was the only big name that might be free, because he had still to commit to McLaren, so I targeted him in Singapore. We had long discussions – backwards, forwards, right, left – and I’d been given indications that Schumacher was going to retire. Lewis was going to re-sign for McLaren on the Monday after Singapore, but I convinced him – in his hotel room, in the middle of the night – to join Mercedes. The arrival of a driver of his calibre stirred the whole team.

“His speed sets him apart. For me he is quicker than Vettel. Look at Spa this year – he won the race even though the Ferrari was potentially quicker. That’s Lewis. There have been ups and downs in the past, because of the intensity of the fight with Nico, but dealing with that was quite easy for me because in my head I’m a driver not a manager. I speak the same language as they do. This year Lewis has been the best guy – though I knew that from day one. F1 will definitely look back on him as one of the all-time greats.”

A club, indeed, of which Niki Lauda has long been a member.

CAREER IN BRIEF

Niki Lauda

Born 22/2/49, Vienna, Austria

1968 Debut in Mini Cooper S; some Austrian Touring Car Championship races in Porsche 911

1969 Formula Vee

1970 F3; sports cars

1971 European F2, 10th; F1 debut in Austria, March 711

1972 F1 March; European F2, fifth; British F2 champion

1973 F1, BRM; ETCC, BMW

1974 F1, Ferrari; maiden GP victory in Spain; ETCC, Ford

1975-77 F1, Ferrari; twice world champion

1978-79 F1, Brabham

1979 Procar champion; retired from racing

1982-85 F1 comeback with McLaren; world champion in ’84; retired at the end of ’85

1993-95Ferrari F1 consultant

2001-02 race director/team principal, Jaguar F1

2012-present non-executive chairman, Mercedes F1; contracted until the end of 2020