“But we could have a laugh. He was a very funny man, loved to muck around. So on the one hand he was a disciplinarian and on the other he was a clown. So you end up thinking, ‘Which bit can I do, then?’ Can I do larking about? Yes. But when you overstepped the mark he’d cut you down, because he had a way of saying the thing that would go to the quick and a lot of people felt the sting of that. But you know, he wasn’t a bad man; he was kind beneath it all. He was a bloody hard worker and lived life to the full. He left a pretty indelible impression.” In an earlier interview, Damon summarised his father’s place in the public’s affections thus: “He had a quality of humanity, which is the thing that makes sports people transcend whatever it is they’ve done. He transcended being just a mere sports person.” The raconteur, the flirt and the clown were the public face. The grimly determined character behind the mask answered to no one.

“He was totally in charge of his own life,” says Damon. “It’s like that recent Niki Lauda tweet where he said, ‘I do whatever I want and no one tells me what to do.’ That applied to dad. They are of a type: self-made men and there was a whole generation of them in Britain in the ’60s. They made their own judgment calls. He said he hated being in the navy, that it was two years wasted. But I don’t know. I think maybe it taught him quite a lot actually.

“If you listen to my dad then listen to Colin Chapman it’s weird; their voices are almost identical. There’s a slightly squeaky intonation with a hint of north London thrown in. Then the tight moustache and the slicked-back hair and their mannerisms. It’s like these people were so long together they became parodies of each other. They were sort of WWII pilot archetypes. You can see how propaganda works. You present a nation being made up of these characters and then people just slot in. David Niven, my dad, Terry Thomas, Errol Flynn – all fit in the same mould. These people formed the archetype, an image that becomes common currency. Just look at Dick Dastardly – that is my dad! In the ’50s they lived out of each others’ pockets. There’s a great picture of my mum with Hazel Chapman on a day out down in Brighton.”

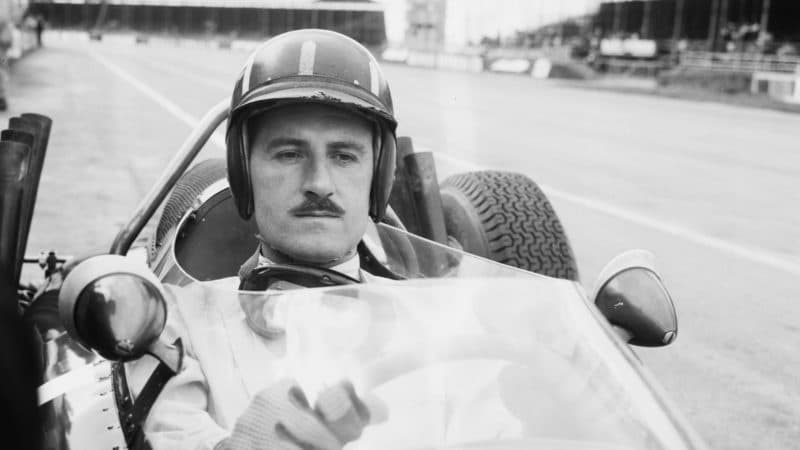

Graham Hill had grown form young charger to statesman of the sport by the time of his death

Grand Prix Photo

Graham Hill and Colin Chapman were of a time and place and each answered only to themselves. But they partnered up – in 1958-59 and again in 1967-69 – through mutual interest. “We used to go to their place,” Damon says, “and even though I was young I always sensed them not fitting together very well. They were each their own men.

“Similarly, I think when Bernie Ecclestone bought Brabham and dad was the driver, Bernie had a bit of trouble accommodating him. Dad, Chapman, Bernie – can you think of any more self-determined, independent characters? Dad was at that time almost transcending the sport, in that he’d become the public face of motor racing. He jokingly called himself ‘The Ambassador’, and he was a galvanising force. So Bernie was having to deal with this guy who was actually getting to that senior position in the sport of being a voice and spokesperson.

“But dad didn’t think in the same way as Bernie. Not many people – if anyone – was going to catch Bernie out but later on, when Bernie began to build up the teams as a group and Dad had his own team, he was not part of that group and I think it may have been that he’d sided with Paul Metternich at the FIA. I’m not sure how that would have all panned out. There was a kind of respect there but Dad and Bernie had similar histories in a way. It was the wild west in those days. Because there were no rules yet telling them what they couldn’t do. Then if anyone said, ‘Hey, that’s not right’ it was too late; they’d already done it. Because of that, they made their own lives. When you get two people together like that they don’t get on very well in the same room.”

![Graham Hill Jo Bonnier 1960 Buenos Aires]](https://motorsportmagazine.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Graham-Hill-Jo-Bonnier-1960-Buenos-Aires-800x450.jpg)