Lunch with Ian Phillips

Messenger boy, writer, editor, circuit boss, charity director, team manager, sponsorship hunter... meet a man of many parts

Charles Best

Something a bit different this month. The subject of this ‘Lunch With…’ is hardly a household name: indeed many motor sport enthusiasts may never have heard of Ian Phillips. Yet he has been a motor racing insider for more than 40 years, from messenger boy to magazine editor, from driver mentor to race circuit manager, from sponsorship hunter to F1 team director. He seems to know absolutely everybody who’s anybody in motor racing, and they all know him. Gregarious, garrulous, irreverent, he is hilarious company, but he is also extremely shrewd. In the secretive world of Formula 1 he has always understood what’s really going on, who’s calling the shots, who is pulling whose financial strings. He’s one of the few who can go up to Bernie Ecclestone, bend down from his six-foot-plus height to mutter the latest scurrilous rumour in the great man’s ear, and be rewarded by a shadow of interest lashing across Mr E’s hatchet features.

Ian lives in a sylvan part of Oxfordshire which has become something of a motor sports enclave. Adrian Newey, David Richards and Adrian Reynard are near neighbours, and a favourite pub is the Nut Tree in the village of Murcott. From its Michelin-starred menu Ian, who likes a decent lunch, selects pavé of smoked salmon and slow-roasted pork belly with celeriac purée and apple gravy, helped on its way by a bottle or two of Provençal rosé.

Something else that’s different about Ian is that I gave him his first job. Some 44 years ago, long before computers, e-mail and mobile phones, i was editor of the weekly magazine Autosport. Freelance race reporters had to send their copy and photographs (known as “words and music”) from Cadwell Park or Ingliston, Castle Combe or Rufforth, by overnight train to reach London early on monday morning. We employed a pensioner who’d spend monday trudging round on public transport to collect each package from the London termini – or in the case of international reports, from Heathrow or Gatwick – and bring it to the printers where my staff of three and I were working round the clock to put the magazine to bed. When the pensioner confessed it was all getting a bit too much for him, I had a brainwave: a lad with a scooter could do the job in half the time. I put a line in the magazine: “Messenger boy wanted. Opportunity to learn about printing and motor sport. Two-wheel licence a necessity.” One reply came from an 18-year-old schoolboy at Malvern College, and there must have been something in his letter that made me pick it out. Ian takes up the story:

Ready to interview F5000 winner Teddy Pilette (with Brands Hatch boss John Webb’s wife Angela standing left)

Motorsport Images

“I came from a motor racing household. My father was an Oxfordshire farmer, but he was friendly with people like Peter Whitehead, Brian Shawe-Taylor and Colonel Michael Head, Patrick’s father. At Le Mans he and my mother used to run the signalling pits for Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton. When you wrote offering an interview I sneaked off school to come to London. I mumbled over the fact that I didn’t have a two-wheel licence, or a scooter: all I had was an extremely battered Ford Anglia. But I made lots of keen noises, and you told me I could start the following Monday. You paid me £8 a week, when the cheapest digs I could find were £8.50 a week. But I was happy spending my Mondays haring around London on my Anglia’s door-handles, my Tuesdays hanging around Heathrow waiting for Denny Hulme to come through Arrivals hand-carrying our Can-Am copy, and the rest of the week soaking up the news and gossip coming into the office. Finally you sent me to Brands Hatch to cover an MG Car Club meeting that nobody else wanted to do.

“Then in January 1971, when you were off in Argentina covering the Buenos Aires 1000Kms – the race when Ignazio Giunti was killed – two of the staff suddenly left in the same week, and then the other was taken ill. The magazine ended up being put to bed by me and Judy, the voluptuous editorial secretary. After that I sort of moved up the ladder, covering more and more races and getting to know more and more people. Roger Williamson became a special mate – he’d won both the ShellSport and Forward Trust F3 titles in 1972 – and he introduced me to his mentor and sponsor, Tom Wheatcroft. Tom was planning to run two F1 Tyrrells in 1974 for Roger and somebody else, and suggested I go and work for him. But a few weeks later, as I was covering an F2 race in Sweden, news iltered through that Roger had been killed at Zandvoort. It was a dreadful shock. That was the end of Tom’s Tyrrell plans – although he’d bought Donington by then, and he said to me, ‘Whenever you want, lad, I’ve got a job for you.’

“Then the guy who’d succeeded you as editor left, and you gave me the job. I’d had no journalistic training, but I loved gossip, and we crammed as much of that as we could into each issue. It wouldn’t have won any design awards, but it was really on the button for news. We succumbed to a few in-jokes, too. Pretty childish, but it seemed hilarious at the time. For example, when Jochen Mass was trying to decide which team to drive for, our headline read: ‘Mass debates’.

“A big part of the whole news-gathering thing was Being Sociable. During the week we used to drink in the Windsor Castle in North Kensington, and soon people realised that the best way to get a story published was to turn up there on a Wednesday or Thursday evening and buy the staff a round. That’s where I irst met Eddie Jordan. This mad Irishman came in, bought a round and said, ‘I’m going to be Ireland’s irst World Champion.’

“The 1970s was a vintage period for British motor racing. I put it down to two heroes of mine, Jimmy Brown who ran Silverstone and John Webb who ran the Grovewood circuits. Plus the hugely respected Nick Syrett and Grahame White, who headed up the BRSCC and the BARC and were able to ensure wonderful entry lists. Webby had an acute commercial eye; he was always ready to try something new. There’d be a proper international meeting somewhere in the UK just about every month, huge F3 grids with rising stars on their way to F1, tremendous stuff in all the other classes too. Great racing, and it attracted great crowds. I even did a bit of racing myself. I shared a Gryphon clubmen’s car with Ollie Sharpley, and his brother Mark shared another Gryphon with young Patrick Head. But as a racing driver I was useless. Part of the problem was I was usually hung over.

Testing Ron Dennis’s Formula 2 Rondel

Motorsport Images

“I editied Autosport for nearly three years, and by the time I was 25 I wanted to do something else. I loved going to races, but the job of editor involved a lot of desk work as well, which wasn’t my thing. In 1976 Tom Wheatcroft convinced me he’d got planning permission for Donington and the circuit was all built, neither of which was strictly true, but off I went to Derbyshire. There was masses to do to get it to the point where races could be run, but in early 1977 we were ready for our first event.

“Or we thought we were. We had the track licence, everything was done, and then 24 hours before we were due to open we were served an enforcement notice. It turned out we hadn’t complied with one planning requirement, which was to cut the earth bank away at one of the entrances to give exiting trafic a better view of the road. But we didn’t own that piece of land. And old Gillies Shields, whose family had owned the Donington Estate, was at loggerheads with Tom and wanted to make dificulties. Fortunately I’d been at school with his son John, who owned the Priesthouse pub at Castle Donington. Over a couple of pints I managed to negotiate with him a quick purchase of that bit of land, we sent in a JCB, and by 5pm the job was done. But it was a nerve-racking moment.

“At the end of that year we ran the final round of the Formula 2 championship, and before that we had a big motorcycle event and Barry Sheene came. That got us about 25,000, which was as many as we could cope with because the perimeter wall wasn’t inished. We had to shell out for lots of police to stop people getting in for nothing. But already Tom was saying, ‘One day I’ll run a Formula 1 race.’

“Tom and I got on well. He wasn’t always the easiest of men, but I could translate what he wanted, and I could make him laugh. The trouble was, too many people took him at face value. But beneath that bluff, genial exterior was a very clever, very wise man. In my life I’ve known two men who didn’t go to school much, probably weren’t too keen on reading and writing, but could add and subtract like you couldn’t believe. And it’s no surprise that Tom and Bernie got on incredibly well. One of Tom’s favourite sayings was, ‘Ever what you want, lad,’ which meant, do whatever you think best. But it was invariably followed by, ‘…but I reckon…’ which was actually an instruction telling you what you were to do. If we were going to a stiff pompous meeting at the RAC he’d say, ‘Now lad, pretend you come from the village.’ Which meant, just act stupid, don’t say anything, and they’ll tell you everything you want to know.

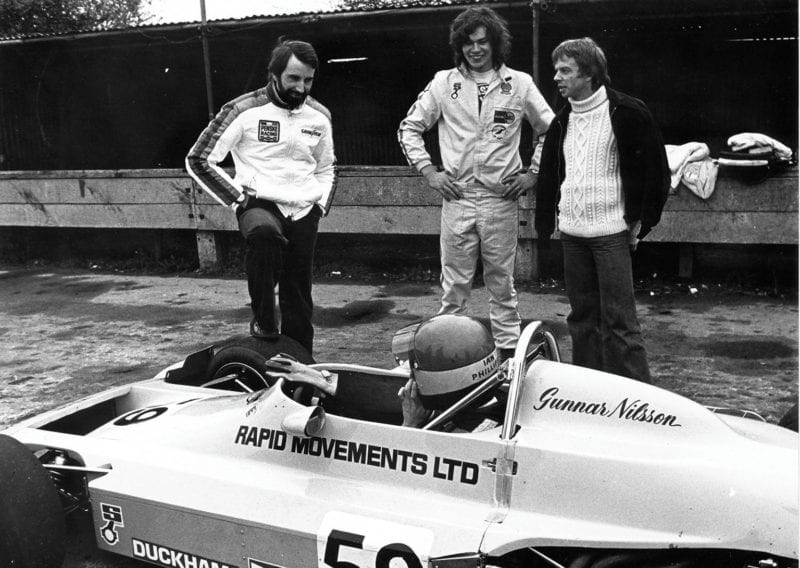

A run in friend Gunnar Nilsson’s Formula Atlantic Chevron, watched by John Watson (left and Chris Witty (centre)

Motorsport Images

“I left Donington to get involved in real international racing again. I moved back to London and my little house in Kensal Rise became somewhere for racing drivers to crash out. Gunnar Nilsson, Derek Daly, Danny Sullivan and lots of others used to camp on our floor. Gunnar became a very close friend, and as he moved up in the racing world he got a house not far from me. During the latter part of the 1977 season – the year he won the Belgian Grand Prix for Lotus – he started to have unexplained pains. One day we were going to a party somewhere and he asked me to drop him off at his doctor’s. He said he’d follow on later, but after that I didn’t hear from him for two weeks. Then he called and said, ‘I’ve been in hospital. I’ve got tumours everywhere.’

“After that I pretty much did nothing else except look after him. I was his taxi driver 24 hours a day until he was spending more and more time in Charing Cross Hospital. He said, ‘I’m going to ight this. I’m not going to let this disease beat me.’ Then at Monza his great, great mate Ronnie Peterson was killed. After that Gunnar seemed to accept he was going to die. He insisted on going to Ronnie’s funeral in Sweden. I picked him up from the airport and that night he had some sort of relapse. Six weeks later he was gone.

“But in those final weeks, with extraordinary determination, he set up a charity to raise money for the hospital that had looked after him. He knew Charing Cross desperately needed funds for new equipment to treat cancer. He had a phone put into his room and was on it all day, calling famous Scandinavians to get them to contribute – Björn Borg, ABBA, Prince Bertil of Sweden. Barrie Gill of CSS, who used to do PR for Team Lotus, helped publicise it, and coming back from Gunnar’s funeral Barrie asked me to run the charity full-time. I didn’t have any option other than to say yes.

“It was an extraordinary time. Charing Cross needed £1.5 million to buy a linear accelerator, which is used in radiation treatment of cancer. These days you’d raise a sum like that in a few weeks, but 35 years ago it was a lot of money. I had massive help from an extraordinary man called David Mason, who’d had a thalidomide child and led the successful campaign to get the drug companies to face up to their responsibility for that. We had great support from drivers, in particular Jackie Stewart and Mario Andretti, who’d been Gunnar’s team-mate in his last season, and we ran a Pro-Am tennis tournament at the NEC with the likes of Hunt, Fittipaldi and Patrese playing stars like Björn Borg and Vitas Gerulaitis. We got that covered by BBC TV.

“Bernie helped us put on a fastest lap competition at Donington and made all the F1 teams send one of their drivers. David Mason flew to Buenos Aires and persuaded Fangio to come over and demonstrate a pre-war Grand Prix Mercedes. We got a good crowd even though the weather was dreadful. Somebody took a great shot of Fangio sideways in the rain, we sent 1000 copies to him in Argentina, and he signed them all for us to sell. And George Harrison donated all the proceeds from his wonderful song Faster to Gunnar’s fund.

Then it turned out that we had to raise another £1 million on top, because Charing Cross needed a building to put the accelerator in. But in 18 months we’d covered it all.

“After that I became a sort of news freelance. I did the news pages for Autosport each week, and by shelling out for this new-fangled thing called a fax machine I was able to sell the same stuff to 11 other outlets round the world. News and gossip was my stock in trade. I had a good address book and a good memory, so I never carried a notebook or a recorder or behaved like a journalist. And I could drink most people under the table, which helped.

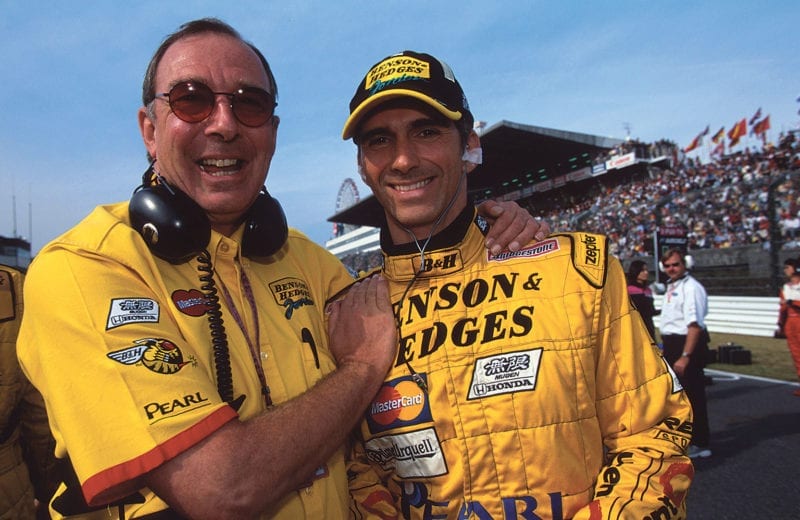

Phillips spent 15 years working for Eddie Jordan

Motorsport Images/Sutton

“I also did PR for Marlboro, Bridgestone, March, anyone who wanted a press release. I did course commentary at Silverstone. And I did some work on the side for Bernie and Max [Mosley], working from that ex-Frank Sinatra glass apartment that Bernie had overlooking the Thames. It was at the height of the battles with FIA President Jean-Marie Balestre, who was suing Autosport over a photo that had been published on my watch of him during World War II wearing Nazi SS uniform – his defence was that he had been a double agent. Max and Bernie were trying to set up the World Federation of Motor Sport in competition to the FIA, and I was well placed to get the inside story for my various outlets. In the end they settled it all with the Concorde Agreement.

***

“I was now helping a lot of young F2 and F3 drivers organise themselves. I did it for free, which I rather regret now, certainly the ones who became World Champions, anyway! But that was a good source of news stories too. And I looked after the Marlboro drivers at the first F3 Macau Grand Prix in 1983. Marlboro Theodore Racing was an amalgamation of Dick Bennetts’ West Surrey Racing and Eddie Jordan Racing. Dick prepared the cars and I’m not quite sure what EJ did, but he made a lot of noise doing it. Ayrton won both races by virtue of his incredible speed on the first lap, on cold tyres. He was simply in a class of his own.

“I went to Japan a lot for Marlboro, looking after Mike Thackwell. Then Leyton House, a Japanese property company, decided they wanted to run a European driver. In 1986 Ivan Capelli was F3000 champion, so we got him over for three Japanese F2 races and I think he won one and was second in one. After that we went to see Leyton House boss Akira Akagi, and he turned to Ivan’s manager Cesare Garibaldi and said, ‘What do you want to do?’ Cesare said, ‘We want to do F1.’ ‘How much will that cost?’ ‘$1.5 million.’ So Akagi wrote out a cheque there and then for $1.5 million and said, ‘You’re in F1.’

“In those days the 3.5-litre normally aspirated cars were coming back, and single-car teams were allowed. So we went to see Robin Herd at March, which had been out of F1 for several seasons, gave him the $1.5 million, and said, ‘That’s to run Ivan.’ Six weeks later Robin called me and said, ‘I can’t find anybody to run this F1 team. I want you to do the job.’ Typical Robin, he said, ‘The factory’s all waiting, everything’s ready to go.’ When I got there the electricity was cut off, the gas was cut off and dear old Gordon Coppuck and Ray Stokoe were working by candlelight to convert an F3000 March into an F1 car. There was I, a journalist who’d spent the past 15 years telling people how bad they were at running a team, suddenly finding out how bad I was.

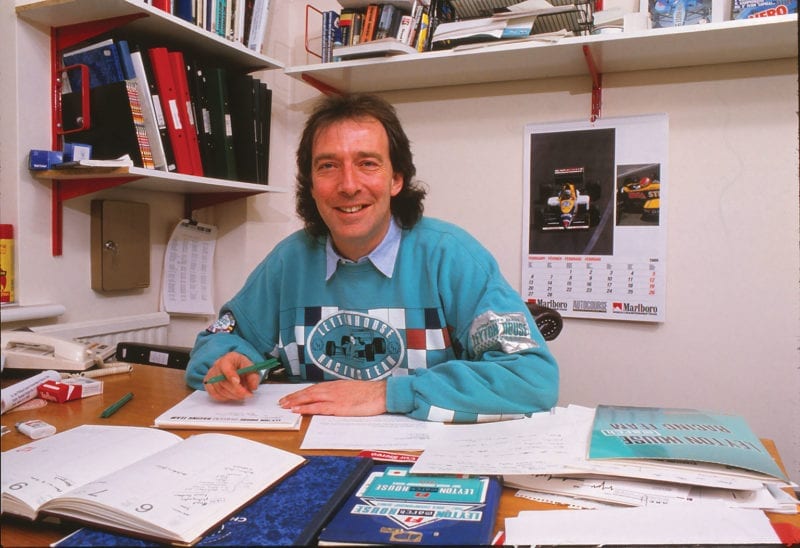

Phillips at his desk in 1989, running the Leyton House team

Motorsport Images

“From the start we had horrendous problems. We got three engines from Heini Mader, went to Brazil for the irst race, blew up one engine on Friday and another on Saturday. So we withdrew. I managed to buy another engine from Frank Williams, we struggled on, and at Monaco we got a point for sixth and were second non-turbo home. Now I’d got Brian Hart, who was meant to be exclusively Tyrrell’s engine builder, to do our engines, and in Austria and Portugal we were first non-turbo home. Ken Tyrrell forgave me for using Brian, because we shared a passion for cricket and that’s all we ever talked about. But I knew we needed to take a step forward, so during that season I said to Robin, ‘We need Newey.’

“I’d known Adrian since he’d engineered Johnny Cecotto in F2 six years earlier. Then he’d gone on to Indycar and Carl Haas. But we got him back very cheaply, he was an absolute bargain. Now I suppose he’s on about £15 million a year. But he is a fabulously nice man as well as a fabulously clever one. No ego at all. The car he designed for 1988 was still called a March, because we didn’t buy ourselves out of March until late 1989, but we were a two-car team now because Mauricio Gugelmin had come in as a paying driver. John Judd had designed an Indycar engine for Honda which had been shelved, so I got Honda’s agreementto use it in F1 form, and I signed an exclusive deal with Judd for nine engines at £100,000 each. Then Frank Williams needed an engine, and he had Mansell and Patrese, so suddenly I no longer had my exclusive.

“But the car that Adrian designed was amazing. It was the smallest F1 car ever, up to that time. We went to Imola for the first test, and the cockpit was so small Ivan had no skin left on the back of his hands after a few laps. There was lots to do, but finally at 3am we all went back to the hotel, leaving Adrian in the garage. When we came back at 6.30am Adrian had made a mould, produced some neat fibreglass fairings to clear Ivan’s hands, and already fitted them to the car. All we had to do was paint them. The guy is a real racer.”

By the end of the season the little Leyton House team was very competitive. In Portugal Ivan qualiied third and inished second, chasing Alain Prost’s McLaren home. In Japan, from fourth on the grid, he was second to Prost’s McLaren by lap six. Ten laps later he passed the McLaren to take the lead – the first time a non-turbo car had led a Grand Prix for four years. But Prost sneaked ahead again, and three laps later the March died and Capelli was out. “We discovered later that Ivan had caught the off-switch with his glove and killed the engine. To this day he says he doesn’t know how he did it, but Adrian did design a very small cockpit.

With Damon Hill, architect of Jordan’s maiden win at Spa in 1998

Motorsport Images/Sutton

“On his day Ivan was spectacularly good, but in January 1989 Cesare Garibaldi, who’d mentored him ever since F3, was killed in a road accident, and that knocked him a bit. By now we’d bought ourselves out of March. Robin was loating the company on the stock exchange, and Adrian wanted out because he said there were too many compromises with what they were making for us, although we still used a lot of March bits. We had our own tiny factory in Bicester, and we called the car CG891 in Cesare’s memory.

“From the start of 1990 we had trouble with our new car: it was an aerodynamic issue to do with the Southampton wind tunnel, and in Brazil neither of our cars qualiied. I developed a massive headache which I thought was the stress of the cars not qualifying, and I flew home as soon as I could. When I got home Bernie came on the phone, wanting the new Concorde Agreement signed, and I said, ‘I’ve got a headache, I can’t get rid of it.’ He said, ‘I’ll tell Sid.’ Ten minutes later I was in Sid Watkins’ hands, and he got me into the Hospital for Infectious Diseases in the Whitechapel Road. Turned out I had meningitis. For the next five months I was completely out of it. I was back for Hungary, but it wasn’t the same. Adrian had gone to Williams and Leyton House was being run by accountants. I finished the 1990 season and then left. In 1991 they ran the Ilmor engine – a deal Adrian and I had set up with Roger Penske – but in 1992 they went bust, and back in Japan Akagi got 14 years for what was then said to be the world’s biggest fraud.

***

“Meanwhile Eddie Jordan told me he was coming into F1 and maybe I’d like to throw in my lot with him. I started with EJ on January 2 1991, and there followed 15 years of incredibly hard work and incredible fun. I think I was called Commercial Director, but the title meant nothing. EJ was a brilliant ideas man. He had the balls, the gift of the gab, and could cover 30 topics in 60 seconds. My job was to translate all that into something that could actually work. And we were a super little group: Gary Anderson was fantastic, of course, and Trevor Foster I’d known since he was Roger Williamson’s F3 mechanic. Getting through the first season is one thing; it’s the second year that’s tough. We started with sponsorship from 7Up, which was Pepsi, and it wasn’t a lot of money, about $1.1 million. The following year we lost them, because they put all their funds into a Michael Jackson tour. But our biggest sponsor that irst year was Marlboro, who paid us $3.5 million to run Andrea de Cesaris. I think I gave them the mirrors for that.

“I was always a big fan of de Cesaris, who was much better than people said. He was erratic, but he was quick. He had experience – it was his 11th F1 season – and he brought money. We needed both. First race, Phoenix, he buzzed the engine and didn’t pre-qualify, then in Brazil he had a huge accident which was probably his fault. Then he settled down. At Monaco he ran in the top six until his throttle linkage broke. Bertrand Gachot was in the other car, and of course he had that altercation with a taxi driver in Shepherd’s Bush, sprayed CS gas in his face, and got locked up just before Spa. That’s how we ended up giving Michael Schumacher his F1 debut.”

Ian then spends the next half-bottle recounting the fascinating tug-of-war with Benetton over Schumacher. Space doesn’t allow it all to appear here, but the climax came in an all-night meeting in the Villa d’Este on the Friday before the Italian GP, Ian and EJ versus Tom Walkinshaw and Flavio Briatore, with Bernie as referee. Jordan ran Roberto Moreno for the next two races, and then Alex Zanardi for the last three. Ian describes Zanardi as “the fastest man who ever raced a Jordan. Ever. Completely out of control, but phenomenally quick. We wanted him for 1992, but we couldn’t afford him.”

On the Donington Park podium with track owner Tom Wheatcroft and Mike Thackwell

Motorsport Images

The list of drivers who went through Jordan over the seasons, and whom Ian looked after, is long. In 1993 the 21-year-old Rubens Barrichello joined from F3000, and was sensational in his third race at Donington. “Everybody talks about Senna’s first lap in the wet in that European GP. But Rubens went from 12th on the grid to fourth on lap one, and ran as high as second. He did four seasons with us, and he and Gary had a great working relationship; they really trusted each other.

“Then from the end of 1993 I had to cope with two Eddies. Irvine had made himself a lot of money racing in Japan and also playing the Hong Kong stock exchange. Within 30 seconds of our meeting he and I just gelled. We had a real roller-coaster ride for the next three years. The guy had total belief in what he was about, and he knew how to play the game. In the end he wanted to go to Ferrari, and Maranello paid us $4 million to buy out his contract. EJ also negotiated Irvine’s salary, which because Ferrari was unreliable at the time included a big bonus every time he retired due to mechanical failure. He did well at Ferrari, then he went off and did three years with Jaguar Racing before quitting F1. He’s worth £400 million now and owns an island in the Bahamas, a yacht club, a property company, a software company, a shipping company. His father, Eddie Sr, sold fifth-hand cars off a Belfast bomb-site. But he was brought up to understand the value of a penny.

“Our sponsor from 1996 was the cigarette brand Benson & Hedges. We convinced them that yellow would work better on the cars than gold, and in the countries where tobacco sponsorship wasn’t allowed their agency, Saatchis, had to think up different wording: Buzzin’ Hornets, Bitten & Hisses with the snake. The best was the same words with four letters left out, Be On Edge, which EJ’s daughter dreamed up. In 1998 we took on Damon Hill for two seasons. It was what B&H wanted. I don’t remember the exact figure, but you’re probably talking £8 million for one season, and you can be sure that B&H paid most of it.

Phillips (closest camera) racing his Clubmans Gryphon at Silverstone in 1973

Motorsport Images

“But to start with things didn’t go well. Up to Hockenheim Damon hadn’t scored a single point. Williams was fourth in the championship at that stage, and we had only the three points that Ralf had scored. I sat Damon down and said, ‘Come on, we can beat Williams.’ And we went from last in the constructors to fourth. Damon scored points in all the remaining rounds save one, and of course he scored our maiden victory at Spa, with Ralf second.

“Then came 1999. To be fair, Damon never did like the new grooved tyres [which were introduced in 1998], and Heinz-Harald Frentzen, his new team-mate who replaced Ralf Schumacher, was flying. Damon told ITV he wanted to quit before he told us. So we sat down, worked it all out, what we were going to pay him, who was going to do what, and he was going to have his last race at Silverstone, with a cavalcade with all his and Graham’s cars. Then we got together to sign it all on the Monday before the race and he never turned up. He’d changed his mind and decided to see out the season.

“Frentzen was a strange guy, but on his day absolutely untouchable. In qualifying at the Nürburgring in ’99 he was still sitting in the pits with five minutes left, hadn’t even done a banker lap, and then he went out and planted it on pole. He was leading the race by miles; then he forgot to press ‘cancel’ on an electronic gizmo we had on the rev limiter, and the car stopped. But he was third in the championship that year. In 2001 he crashed coming out of the Monaco tunnel, which gave him a bad bang on the head. After that he was off the pace. We had a lot of German sponsorship from Deutsche Post, but EJ decided he had to go. So we sacked him immediately before the German Grand Prix. Not a good idea. Driving into the circuit the locals were trying to turn over our minibus, and there were ‘Jordan F*** Off’ signs in the stands. After two races with Ricardo Zonta we took on Jean Alesi, who of course had driven for Eddie in F3000. Jean is a wonderful man who always galvanised any team he joined. He did his last five Grands Prix for us, and was in the points at Spa.

“Our relationship with Honda was always very good. But we were their No 2, because BAR was the works team even though it was an unhappy ship from Day One. To be fair Honda did try to buy Jordan Grand Prix, and offered Eddie £60 million. He went away with Marie to think about it, but decided it was unfinished business. We hadn’t won a race at that point. Later on he sold 49 per cent of the team to a private equity bank for £40 million, so he secured himself and his family. But five years later the writing was on the wall for the smaller teams, the manufacturers were coming back in, and Honda bought itself out of its contract. Suddenly we had to pay for our engines again. In 2003 we were with Cosworth, very much the poor relation to Jaguar. Ford charged us $22 million and we had 27 blow-ups. Giancarlo Fisichella won in Brazil for Jordan in 2003, Ford’s final F1 victory. They still didn’t like us.

A very hairy Phillips listens in at Brands Hatch in 1971 as James Hunt and Niki Lauda chat, while Max Mosley strikes a contemplative pose

Motorsport Images

“In 2005 after a constructors’ meeting at Heathrow Bernie said to Eddie, ‘I’ll give you a lift back to town – there’s someone I want you to meet.’ That was Alex Schnaider. Six weeks later EJ had sold the team. The day the deal

was signed Eddie sat in my office in floods of tears saying, ‘I’m a failure.’ I told him, ‘EJ, you’re anything but a failure. You’ve created a great team, we’ve all got jobs and you’re rich’.”

So after working so closely with EJ for 15 years, Ian found himself responsible to a Russian commodities trader whom he’d never met. “In fact Alex didn’t really get involved. He renamed the team Midland, but he sold it again within seven months to Michiel Mol and Spyker. Colin Kolles, who’d been running an F3 team, was brought in, and initially I didn’t really have a job apart from them coming to me and saying, ‘How does this work?’ Then I think Toyota, with whom I’d originally done the 2005 engine deal, asked for me to be more involved. But Midland was now a back of the grid team. In 2007 the Spyker share was sold to Vijay Mallya and the team became Force India.

***

“I think it’s fair to say that Vijay and I disliked each other from Day One. He’s a very rude man. His father founded Kingfisher Breweries in India way back in the 1950s and he inherited it, a huge sales and distribution organisation, when he was 28. We really fell out after the 2009 Belgian Grand Prix, when Fisichella took pole and finished second less than a second behind Räikkönen’s Ferrari. After that he banned me from going to races because he said too many journalists were talking to me and I was on telly too often.

“But it was probably the best thing that could have happened. I was nearly 60, I’d been on the road pretty much for 40 years, and I didn’t realise it but I was tired. My first marriage had lasted 19 years – that was to Murleen, an American girl I met when she was working in the Tootsies’ hamburger restaurant in Notting Hill. We tied the knot on a boat in the harbour during the Monaco Grand Prix, and we had three kids and now five grandchildren. Then in 1997 at the Argentine GP I met Sam Howe, fashion editor of The Sun. We’ve been together for 16 years now, and our son Oscar is 10.

“After Force India I relaxed for nine months, went to the gym, lost 25kg. Then I spent the 2011 season as Chief Operating Oficer at Marussia, and pulled it all together with the Manor Motorsport guys into the old Ascari sports car factory in Banbury. The plan was to amalgamate Marussia and Caterham, and Bernie was keen for it to happen, because he’d rather have one strong team than two weak ones. The deal was done, but it fell apart in the detail. I finished with them in September 2012, but carried on as a consultant for a while. And I’m still working now. I’ve got one or two things on the go which I can’t talk about. And I’m helping a couple of young drivers.

“If I hadn’t written you that letter from school in 1969, I suppose I’d have ended up a farmer, like my dad. Instead I’ve had an extraordinary time: I won’t call it a career, more a way of life. There have been ups and there have been downs, but I wouldn’t have missed a single minute of any of it. So I’m pretty pleased that, 44 years ago, you somehow picked my letter out of the pile.”